Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club

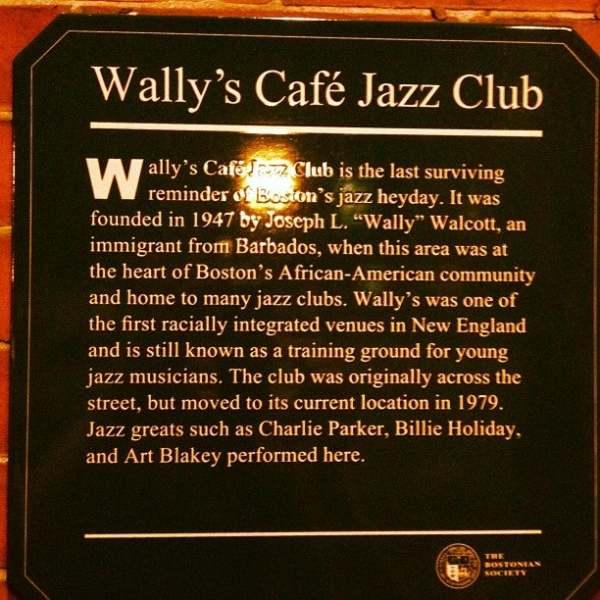

As the oldest jazz club in Boston, Wally’s Cafe is as historic as it gets in a musical context. And the Bostonian Society acknowledged that in 2009 when it honored the venerated venue with an historical marker, calling it “the last surviving reminder of Boston’s jazz heyday.”

But Wally’s is also deeply significant on a broader, sociocultural level since it was the first Black-owned nightclub in New England and the first to be granted a liquor license, a stark reminder of those not-so-good-ole days when the official Jim Crow laws of the South were often practiced in the North, just not quite as explicitly.

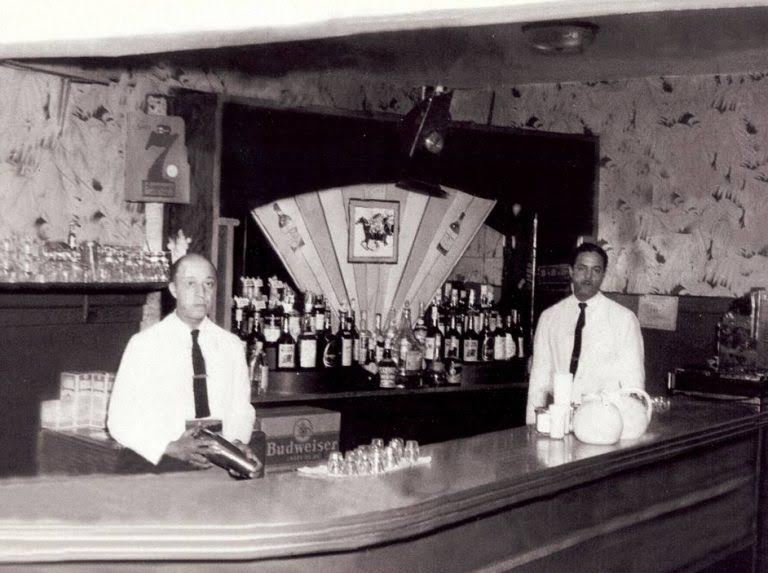

Originally called Wally’s Paradise, the club opened at 428 Massachusetts Avenue on January 1, 1947, three and a half months before another landmark event in US racial equality, Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 11. In the 76 years since, Wally’s has hosted a legion of legends and, along with other Boston and Boston-area clubs in the 1940s and ‘50s like The Hi-Hat, Chicken Lane, the Savoy Cafe, the Ken Club, the Wig Wam, Morley’s (“the Big M”), the Roseland-State Ballroom and Storyville, has played an enormous role in introducing jazz to greater New England.

JOSEPH L. “WALLY” WALCOTT, JAMES CURLEY, HANDS-ON APPROACH

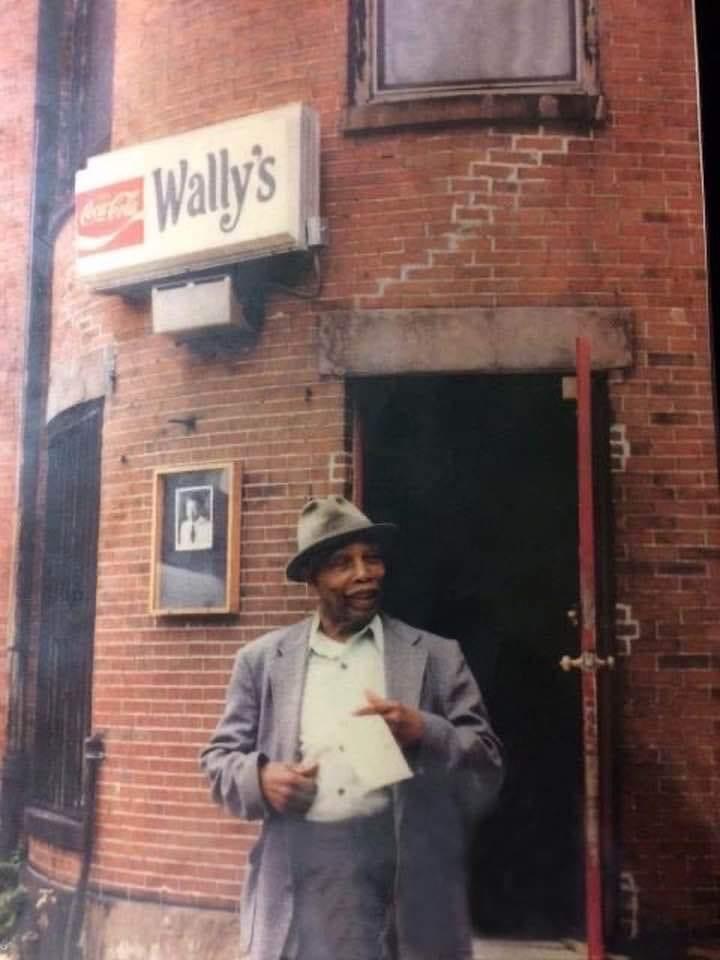

The club was owned by Joseph L. “Wally” Walcott, who emigrated to the US from Barbados through Ellis Island in 1910, at age 13, and settled in Boston, where two of his brothers were living already. During Prohibition (1920-1933), while living at 610 Columbus Avenue, he operated a speakeasy – known then as a “buffet flat” in African-American communities – and held a variety of jobs, eventually saving enough cash to start his own taxi business. His lifelong vision of the American dream was to own a nightclub.

In the fall of 1945, Walcott’s taxi business opened the door to his dream coming true when one of his fares was then-US Congressman James Curley, who’d served three non-consecutive terms as mayor of Boston and was running for a fourth that year. When Walcott told Curley about his hopes of opening a club, the career politician promised to do whatever he could to help secure him a liquor license if he was reelected, in the belief that assisting Walcott would earn him Black votes in the November election. Curley won handily with almost 46% of the vote in the five-candidate race, and Walcott’s license application was approved by the fall of 1946.

Knowing that the club’s survival required attracting the hottest talent, Walcott took a hands-on approach, often driving to New York City to persuade the jazz musicians based there to play at Wally’s, even driving them back to Boston himself if doing so would seal the deal. With that commitment and passion, he turned Wally’s into a swingin’ space that united Bostonians of all races at a time of strict segregation, one in which world-class music allowed patrons to transcend the bitter realities of the city’s institutionalized racial divide. “He put together a platform where everyone from all walks of life could come and enjoy the arts,” his grandson, Paul Poindexter, told The Boston Globe in 2022.

NOTABLE APPEARANCES, STUDENT MUSIC PROJECT

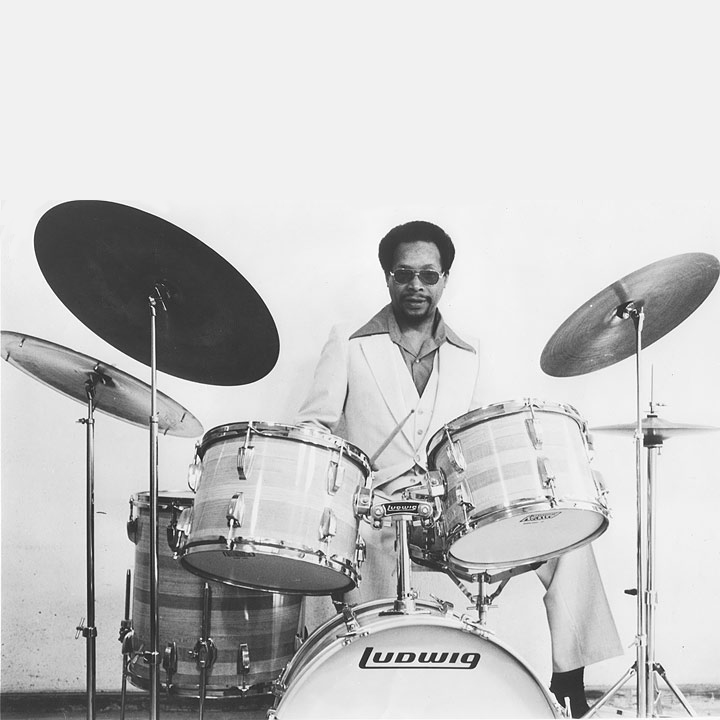

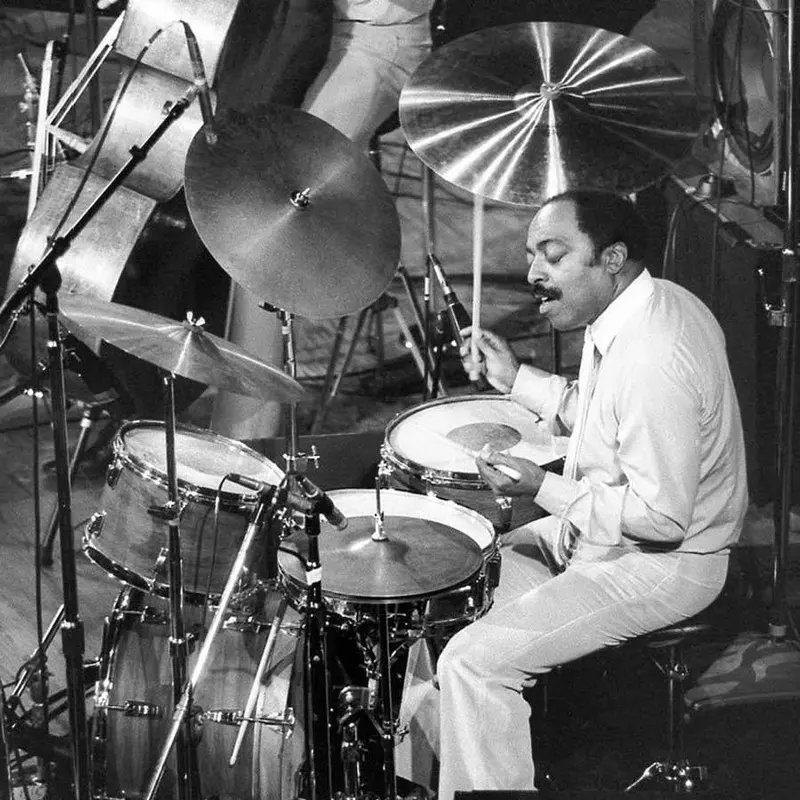

From the late ‘40s and through the ‘50s, Wally’s provided jazz aficionados with appearances by jazz giants including Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Art Blakey, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, Cannonball Adderley and Paul “Fat Man” Robinson. The club also featured an impressive assortment of Boston-rooted talent such as saxophonists Art Foxall, Jimmy Tyler, Charlie Mariano, Boots Mussulli and Serge Chaloff, bassist Lloyd Trotman, trumpeters Joe Gordon and Herb Pomeroy, pianists Sabby Lewis, Mabel Robinson Simms, Nat Pierce and Dick Twardzik, multi-instrumentalist Jaki Byard and drummers Alan Dawson and Roy Haynes.

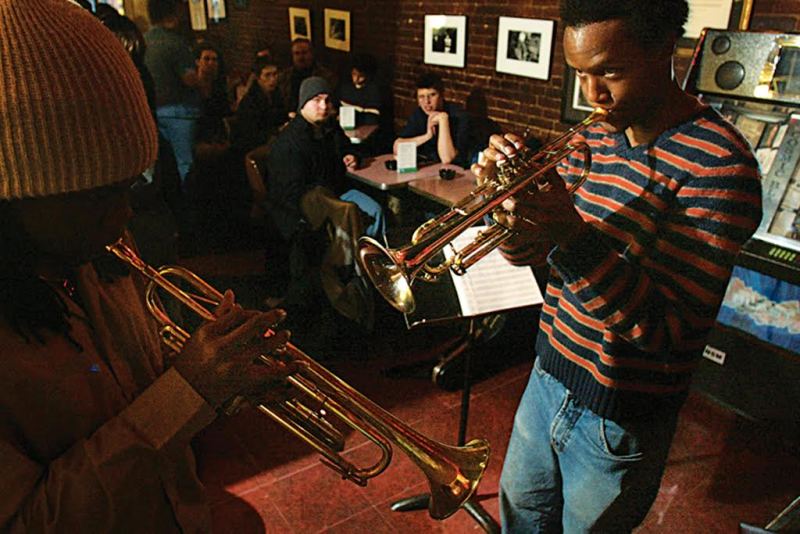

Along with presenting some of the genre’s brightest stars, Wally’s has showcased a steady stream of future Grammy winners years before they achieved national recognition, including bassist Esperanza Spalding and keyboardist Jeff Bhasker, thanks to its proximity to Berklee College of Music, Boston Conservatory at Berklee and New England Conservatory.

In 1960, Walcott renamed the venue Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club and started inviting students from Berklee, Boston Conservatory, New England Conservatory, Harvard, MIT and Boston University to join seasoned musicians on stage – even providing some of them with housing in the apartments above the club – which made Wally’s the public training ground that it remains today through its Student Music Project (SMP). While the initiative’s focus is providing a place for student musicians to train SMP participants in a live setting, the program was designed to foster skills beyond musicianship alone; it develops “discipline, time management, creativity and team building,” according to the official Wally’s website.

1979 RELOCATION

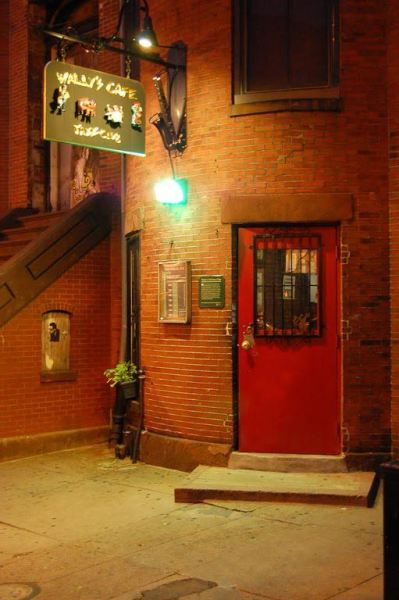

In 1979, Wally’s moved across the street from its original location to its current address, 427 Massachusetts Avenue, after the Boston Redevelopment Authority took control of 428 Massachusetts Avenue by eminent domain (to build a highway that never materialized). While the first spot was significantly more spacious than the second, with a dance floor, three bars and a full kitchen downstairs, the tiny underground space stands out amidst the South End’s brownstones today with its bright-red door and distinctive sign, which spells out “Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club” with carvings of jazz-musician caricatures in the center; the brackets that attach the sign to the brick building are in the shape of a saxophone.

According to Walcott’s daughter, Elynor Walcott Poindexter, her father wanted to move to a substantially larger space, but she convinced him otherwise, using very simple commercial logic. “He was looking for a much bigger place, but I took him across the street,” she told Boston magazine in 2021. “It was just him and me looking through the window of the abandoned building. He said, ‘In here? This itty-bitty place?’ I said, ‘Yeah, ‘cause when people come to Wally’s and see that it’s closed, they’ll say, ‘Where’s Wally’s?’, then they’ll just turn their heads and they’ll say, ‘Oh, there it is!’ And I was right!”

CURRENT OWNERSHIP, SCHEDULE

In 1998, the year after Wally’s received the “historic” label from the City of Boston’s Business Heritage Project, Walcott passed away at age 101, but the club remains in his family to this day, run by Elynor and her three sons, Paul, Frank and Lloyd Poindexter. Wally’s is open 365 days a year, with three different bands appearing between 5pm and 1am.

Most of the groups are comprised of professional musicians but others are made up of students honing their craft, particularly during the first set (5:00-7:00 pm), which is usually a jam session. The musical themes of the second and third sets vary depending on the day of the week: jazz on Fridays and Saturdays; funk on Sundays, Tuesday and Wednesdays; blues on Mondays; and Latin jazz and salsa on Thursdays.

SURVIVING COVID-19 SHUTDOWNS

From March 2020 until September 2022, Wally’s was closed due to restrictions on public gatherings following the coronavirus outbreak. During the pandemic, people from all walks of life came together to keep the club afloat with financial assistance, and a GoFundMe effort helped to establish the Student-to-Student Music Cafe, an online space where musicians create podcasts, give/take lessons and collaborate virtually on various projects.

“The community stepped up and took care of us [since they] believe in our mission, so we got great support,” Frank Poindexter told Boston Public Radio several days after the club reopened, adding that Wally’s is lucky to be in Boston. “We have world-class talent in this city, we have great, super institutions in this city, so we’re super fortunate,” he said.

LEGACY

Speaking with Boston magazine in January 2021, jazz historian Richard Vacca, author of The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Troy Street Publishing, 2012), highlighted how groundbreaking Wally’s was from its very foundation.

“In 1947, when Wally’s opened, there were already two jazz clubs on that block, but both were owned by white guys,” he said. “So I think it was really important from a neighborhood point of view, maybe from a pride point of view, that here was the first time that a nightclub in New England was owned and operated by a Black guy. This was finally a place where people could get together and relax without having to worry about admissions criteria or any of that kind of stuff. In other words, they could be served.”

In the same interview, Vacca talked about how Wally’s spearheaded the eventual dissolution of racial barriers in other local jazz establishments, something that was downright unimaginable in pre-World War II Boston.

“Until 1948, the Hi-Hat [a popular jazz club in the same neighborhood as Wally’s] was whites-only. The only Black people that were in the place before 1948 were serving the food, washing the dishes and so forth,” he said. “Wally’s attracted a crowd, and the guys who owned the Hi-Hat saw what was going on. And the very next year they converted from being a whites-only dine-and-dance place to a jazz club with an open-door, colorblind-admissions policy. So, Wally’s had a big effect on the neighborhood and in the community.”

(by D.S. Monahan)