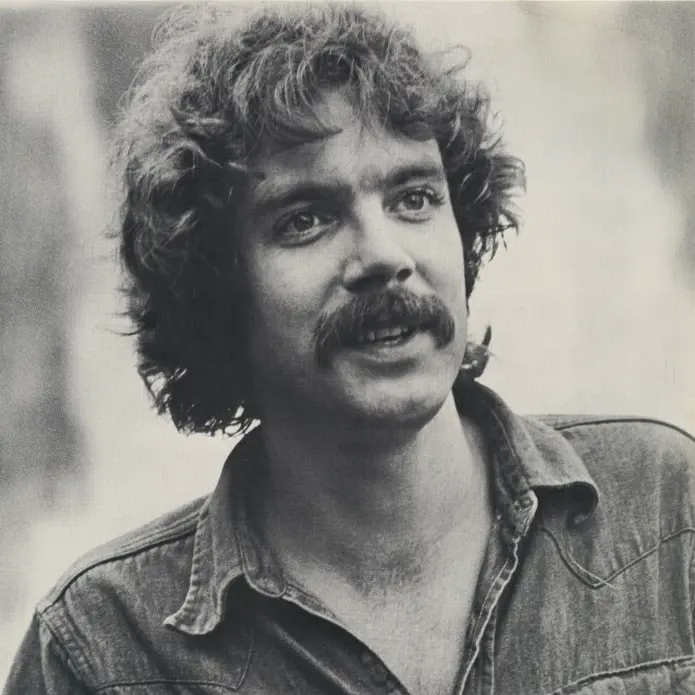

Tom Rush

A slew of rock and pop icons have taken on snappy stage names, of course. From Jiles Perry Richardson Jr. (The Big Bopper) and Reginald Kenneth Dwight (Elton John) to James Newell Osterberg (Iggy Pop) and Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta (Lady Gaga), compiling a full list would be like guessing how many times Ellas Otha Bates (Bo Diddley) played “Bo Diddley.”

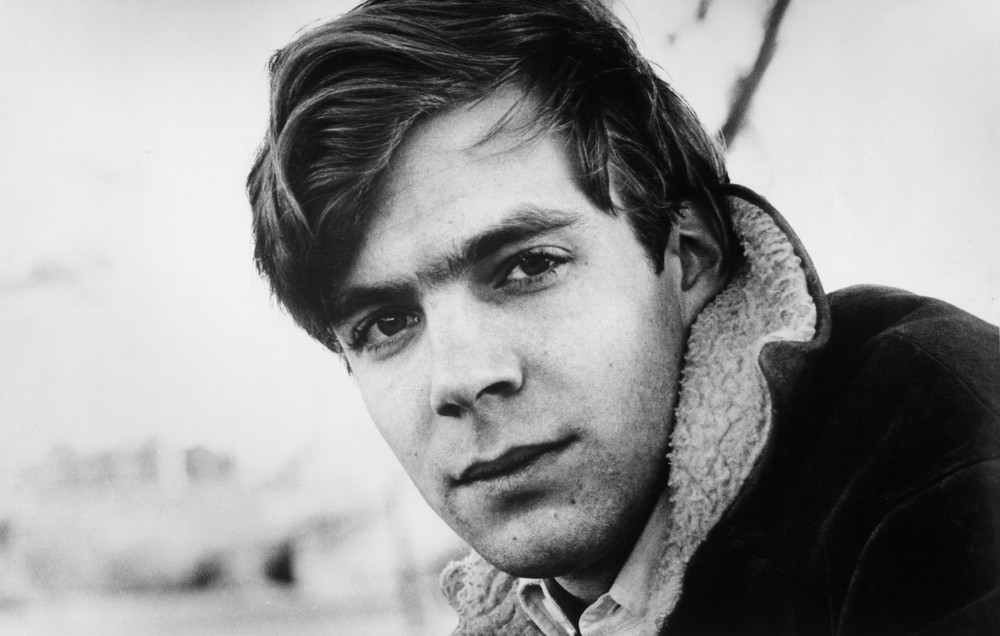

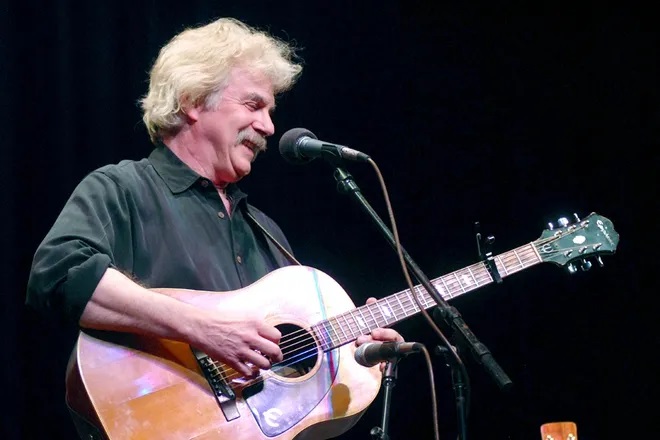

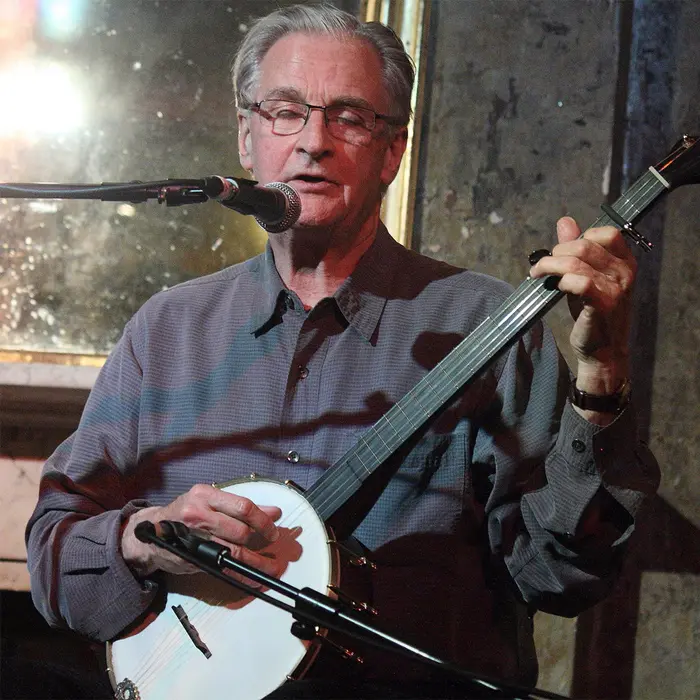

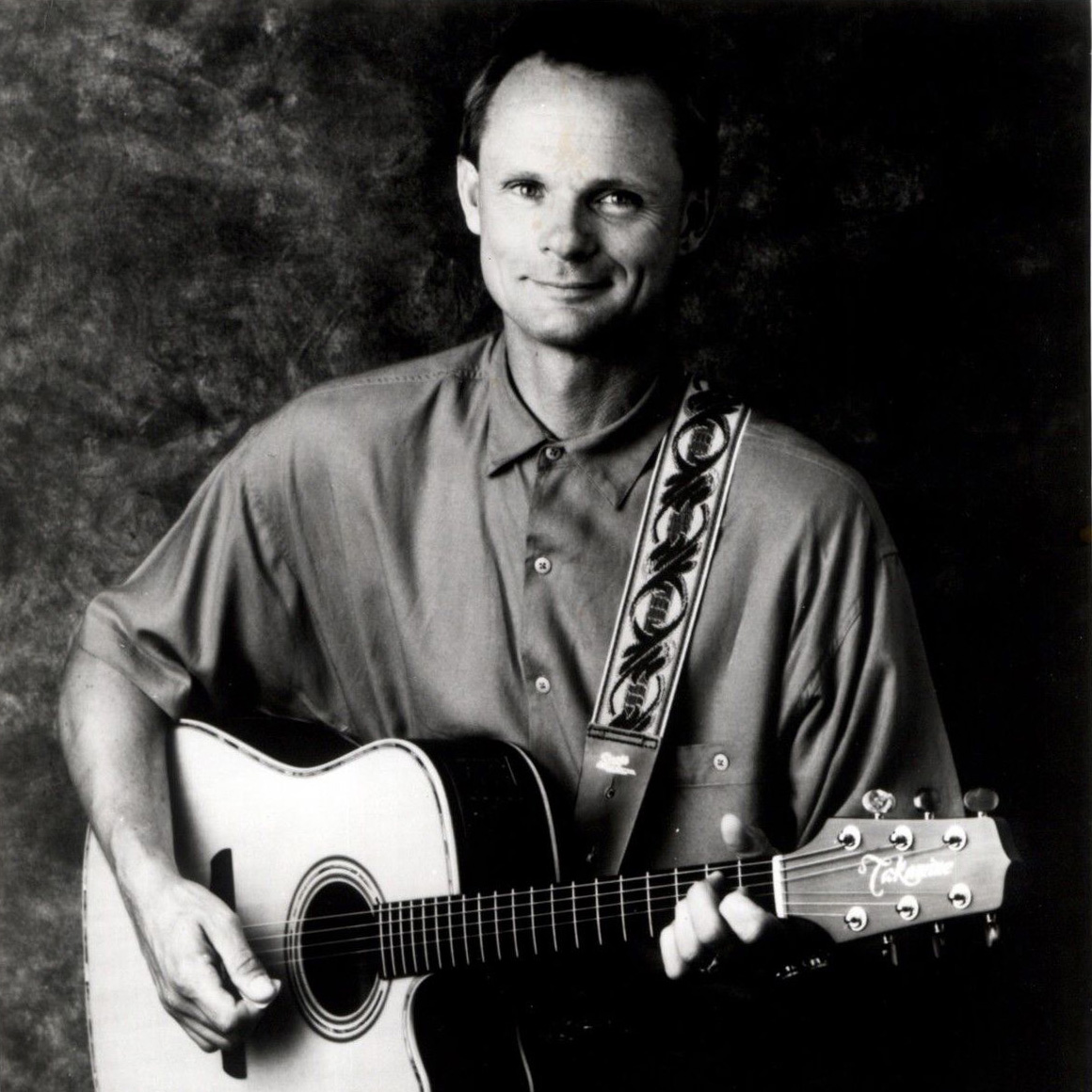

And then there’s Tom Rush who, along with Eric von Schmidt, was as elemental to the Cambridge folk scene in early 1960s as Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk were to the one in Greenwich Village. His supremely snappy, stageworthy moniker happens to be his real name and – like Elvis’s, Madonna’s, Prince’s and Neil Diamond’s – may have predestined him for a life in the limelight but, quite unlike those megastars, Rush remains the polar opposite of a glammed-up pop icon. Despite all the recognition he’s garnered over 60 years and 18 LPs, he seems refreshingly incapable of pretending to be anybody other than who he is, in name or otherwise: an old-school troubadour laser-focused on his vision, his values and his art in an upliftingly unpretentious way.

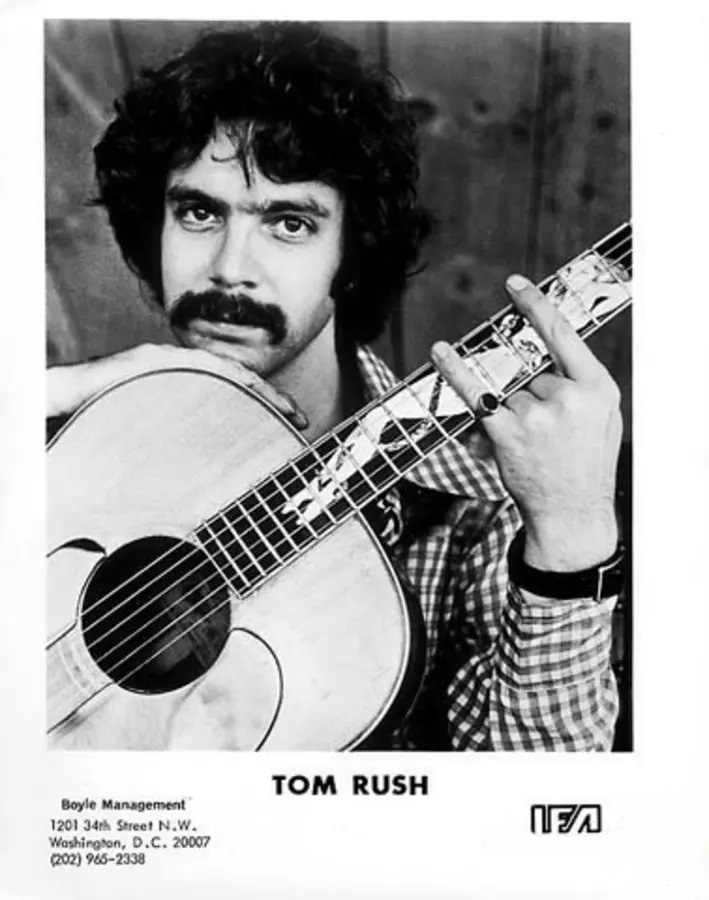

Credited with helping to launch the careers of James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne and others by recording and performing their songs before fame knocked on their doors, Rush combines his distinctive guitar style and warm voice with songs about love, loss, freedom and redemption. His wry on-stage humor sometimes sends audiences into fits of laughter and his blend of melancholic ballads and gritty blues often leaves critics struggling to categorize his music, although “folk” is most common – against his wishes. “Academically, a folk song is a song that has no author,” he said in 1999. “They’re traditional songs handed down by ear from generation to generation. I do not consider my stuff ‘folk music’ because it doesn’t fit that definition. Nowadays, the meaning of ‘folk’ is really so broad that it doesn’t mean anything.”

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, EARLY APPEARANCES

Born on February 8, 1941, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and raised in Concord, his father taught at that city’s prestigious St. Paul’s School and Rush graduated from the equally elite Groton School in Massachusetts before enrolling at Harvard in 1959. After one year majoring in biology, he studied English Literature, graduating in 1963. By age 14, he’d learned ukulele, at 15 he began playing guitar and while at Harvard he hosted a folk program on WHRB but he never considered music as a profession until his early 20s. “The fact that I have an English Lit degree is why I am a musician,” he once said. “I couldn’t make a living on it.”

And his first time on stage was entirely involuntary; it was a punishment for having snuck beer into a hootenanny, where he was scouting potential guests for his radio show, as he told WBUR in 2021. “I discovered you could get in for free if you had a guitar. Then I discovered you could get in for free if you had a guitar case,” he said. “So I’d put a six-pack in my case and head off to the hootenanny. I got caught one night at The Golden Vanity [and they called me up] on stage. I borrowed a guitar. I don’t remember what I did because I was so nervous. Apparently it went well enough, because the owner called me back a couple weeks later, and one thing led to another.”

The first places that experience led him were the Unicorn Coffee House and Club Mount Auburn 47 (which became Club 47 in 1963), and he started playing regularly at both in early 1962. In March that year he was featured in the debut issue of the Cambridge-based bi-weekly The Broadside and just 16 months later, in July 1963, Rush debuted at the esteemed Gerde’s Folk City in New York. Throughout 1964/65 he gigged across the northeast, including shows at the King’s Rook in Ipswich (later Stonehenge Club) while maintaining his regular Unicorn and Club 47 schedules.

FIRST ALBUMS, ELEKTRA SIGNING, TAKE A LITTLE WALK WITH ME

While still at Harvard, Rush recorded two LPs, 1962’s Tom Rush at the Unicorn, a live album on LyCornu Records, and 1963’s Prestige/Folklore release Got a Mind to Ramble, the latter produced Paul Rothchild (future producer of The Doors and Janis Joplin). The latter of the two featured jug and washtub-bass ace Fritz Richmond of Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band and the Geoff Muldaur-penned “Mole’s Moan.” In 1964, the 23-year old Rush recorded his third album, Blues, Songs and Ballads, also for Prestige/Folklore.

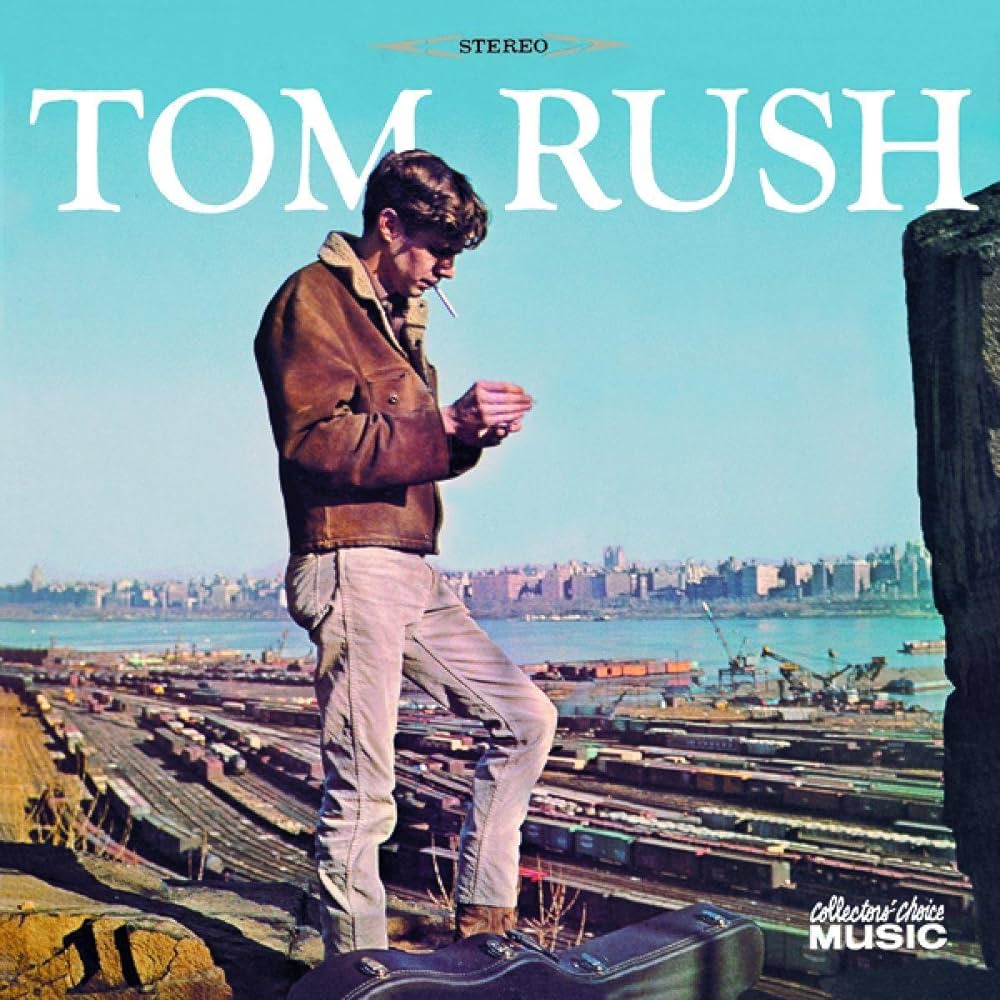

In 1965, Rush signed with Elektra and recorded a self-titled album of traditionals and two Woody Guthrie songs – no originals. He demonstrated his songwriting skills on his next LP, however, 1966’s Take a Little Walk with Me, with the songs “On the Road Again” and “Galveston Flood,” the latter of which he co-wrote with International Bluegrass Hall of Honor member John Duffey. The album also includes Willie Dixon, Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly covers, establishing Rush’s reputation as a superb interpreter of other people’s material.

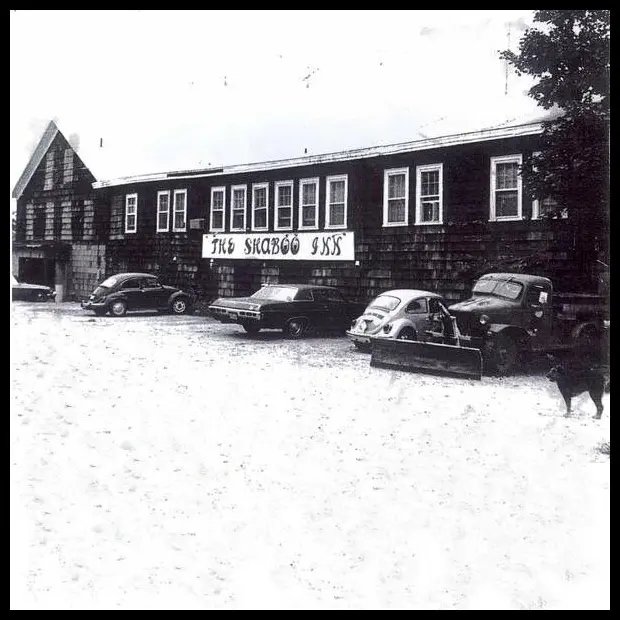

His notoriety grew so quickly that in October 1966 he debuted at the most prestigious venue in New England, Boston’s Symphony Hall, and went on to appear there six more times (1967, 1973, 1981, 2012, 2013, 2014), more than any other artist of his genre. Rush has played at a bevy of other notable New England spots including The Boston Tea Party, Music Inn, the Orpheum Theatre, Tanglewood, the Shaboo Inn, Iron Horse Music Hall and The Bull Run.

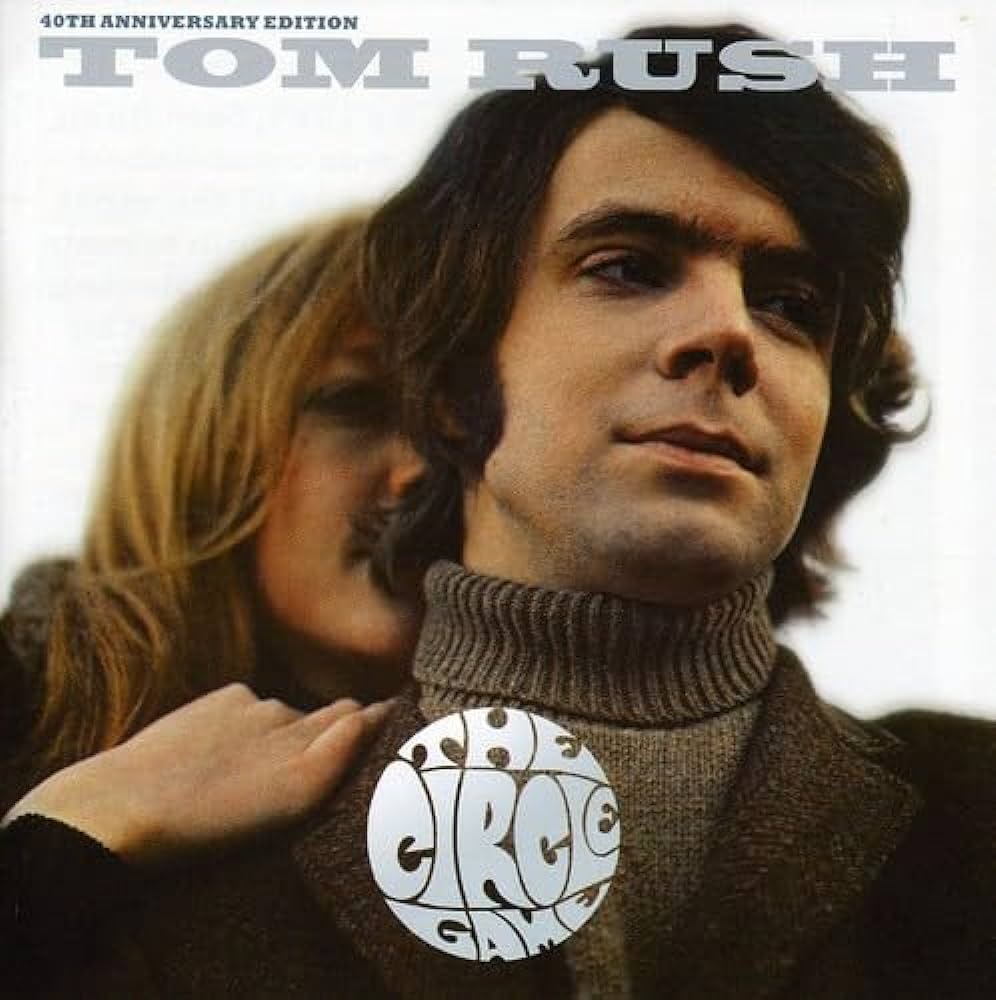

THE CIRCLE GAME, “NO REGRETS” VIDEO, COLUMBIA SIGNING

In 1968, Rush’s career soared with the release of The Circle Game, which included two originals, “Rockport Sunday” and “No Regrets,” and covers of Joni Mitchell, James Taylor and Jackson Browne songs that had not yet appeared on those artists’ own albums. In an innovative move 13 years before the MTV revolution, Elektra made a video for “No Regrets,” now his best-known tune and a folk standard.

In 1970, Rush moved to Columbia Records to record four rock-oriented albums that reached the middle range of the Billboard 200: Tom Rush (1970, #76) Wrong End of the Rainbow (1970, #110), Merrimack County (1972, #128) and Ladies Love Outlaws (1973, #124), the last of which included contributions from Carly Simon and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter. Exhausted from non-stop touring, he spent the second half of the ‘70s away from the music business.

NEW YEAR, LIGHT NIGHT RADIO, CLUB 47 SERIES, WORK IN PROGRESS

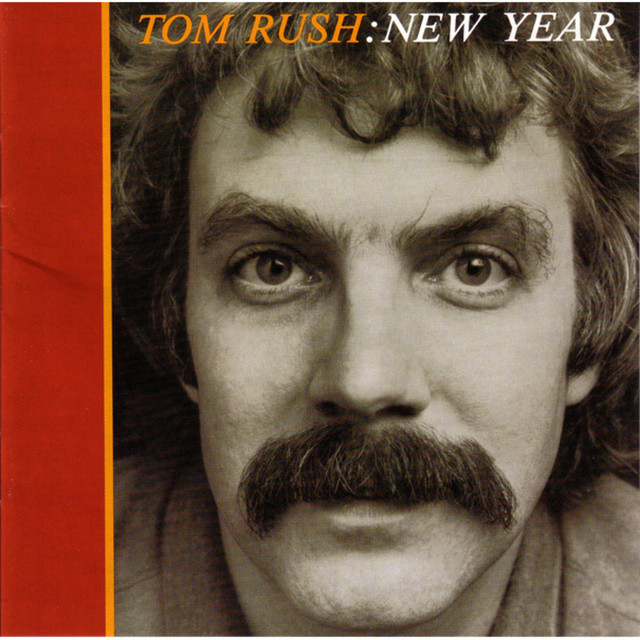

In 1981, Rush returned to the stage with panache, selling out Symphony Hall. The show was recorded and released in 1982 as New Year on Rush’s new Night Light Label. He followed with 1984’s Late Night Radio, a 12-track disc with seven originals and in March 1986 he debuted at Carnegie Hall.

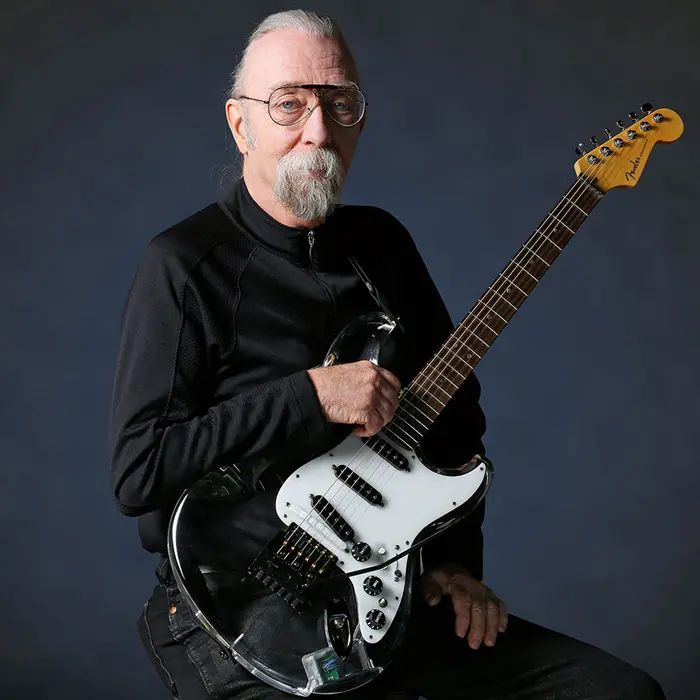

Wanting to create a forum for unknown artists like Club 47 had been for him 20 years before, in the early ‘80s Rush established the Club 47 Series, concerts in which established artists including Bonnie Raitt appear alongside up-and-comers like the then-unknown Alison Krauss. The series’ concerts have been broadcast on PBS and NPR and fill venues across the US to this day.

In the 1990s, Rush continued performing but took a break from recording except for the limited-edition cassette EP Work in Progress (1994). In 1999, Columbia/Legacy issued The Very Best of Tom Rush: No Regrets, which includes one new original, “River Song.”

2000S ALBUMS, CLUB 47 DOCUMENTARY

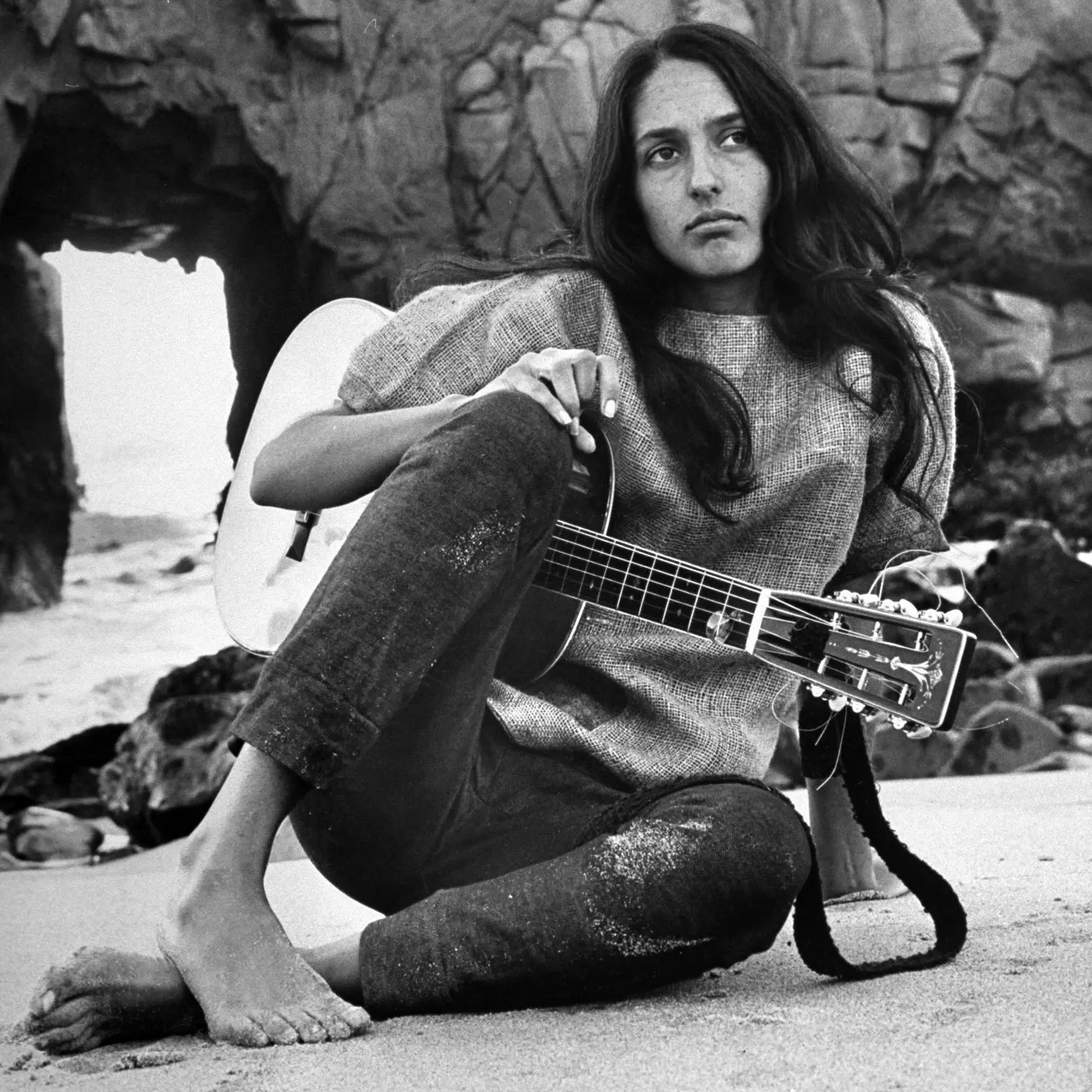

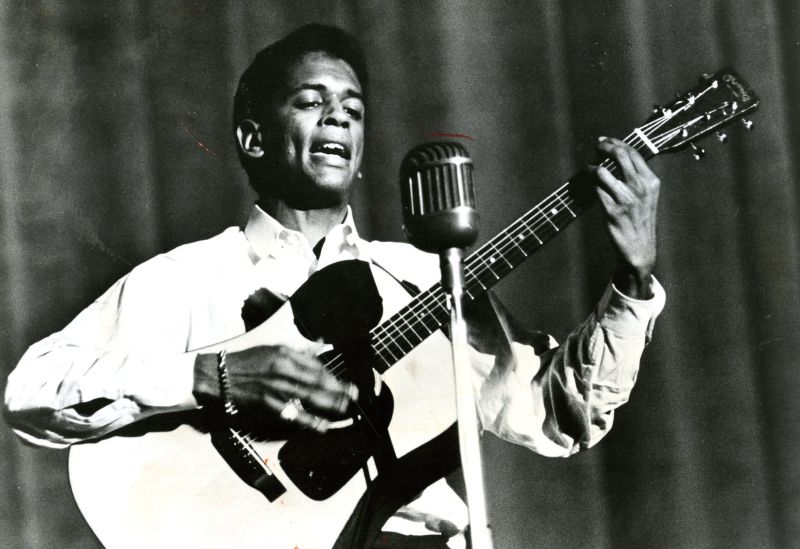

In the 2000s, with his popularity boosted by 2001’s Live at Symphony, Boston, Rush returned to the studio to record five albums: 2006’s Trolling for Owls, 2009’s What I Know (produced by former Club 47 manager Jim Rooney), 2013’s Celebrates 50 Years of Music (recorded live at Symphony Hall and featuring Jonathan Edwards, Geoff Muldaur, Maria Muldaur, Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band and others) and 2018’s Voices (also Rooney-produced) and 2024’s Gardens Old, Flowers New. In 2013, Rush appeared in the documentary For the Love of the Music: the Club 47 Folk Revival along with the Muldaurs, Rooney, Kweskin, Joan Baez, Jackie Washington and Taj Mahal.

COMMENTS ON SONGWRITING PROCESS

Asked in 2018 about his songwriting process, Rush said it’s far more ethereal than cerebral. “To me, it feels like the songs already exist and I’m just trying to coax them into this universe,” he explained. “It’s like listening to a faraway radio station that fades in and out. Each time it fades in, I get a little bit more of the song.”

(by D.S. Monahan)