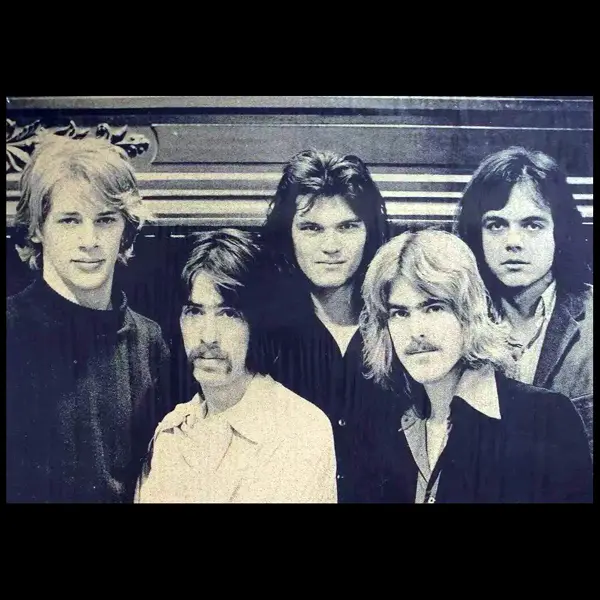

The Sidewinders

Former WBCN deejay Carter Alan summarized The Sidewinders particularly well in 2012, calling them “a band that could have been God, but wasn’t,” writing that the group is legendary not for what it was as a unit per se but rather “for what its members would go on to accomplish.” And that’s not damning with faint praise; it’s a tribute most musicians would welcome wholeheartedly – and one that The Sidewinders deserve in spades.

An early-‘70s power-pop combo born on the quaint, cobblestoned streets around Harvard University, The Sidewinders recorded only one album (a commercial bust but a critical smash) yet were creatively fertile enough to spawn several members of significant Boston acts from various rock subgenres – The Paley Brothers, The Modern Lovers and Nervous Eaters – in addition to the future musical director of Tom Rush’s band and a singer-songwriter-guitarist who – pardon the pornographic pun – “stroked” his way up to #3 in the Billboard Top Tracks chart in 1981, Billy Squier.

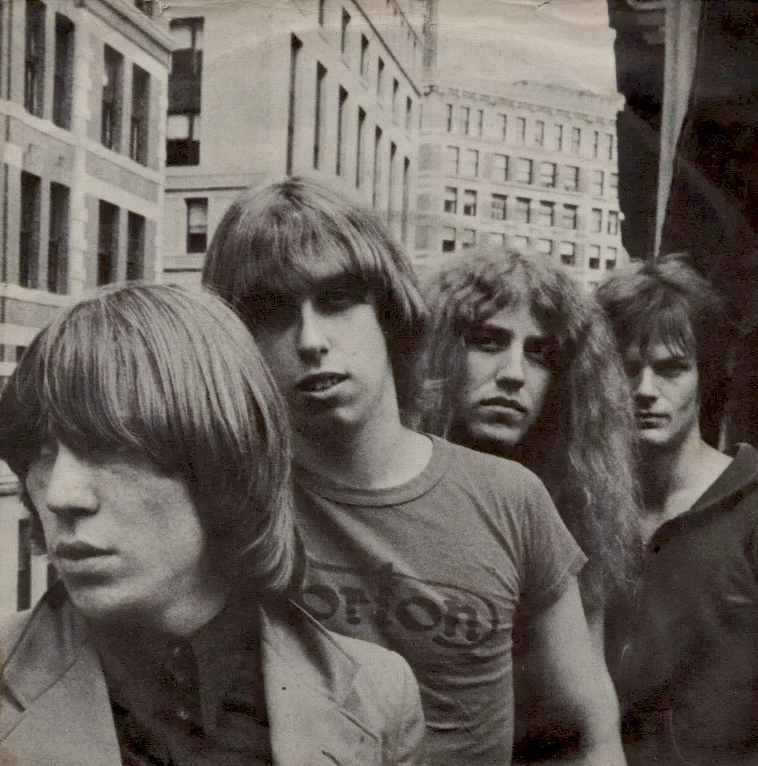

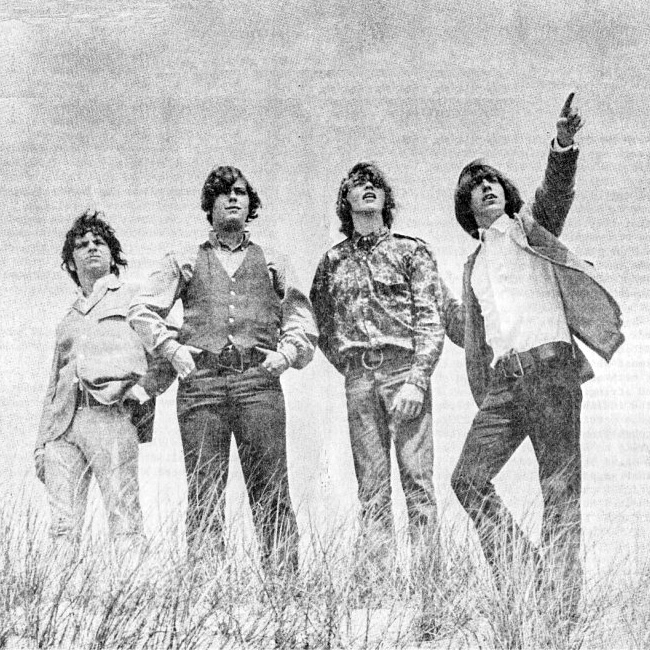

FORMATION, EARLY APPEARANCES

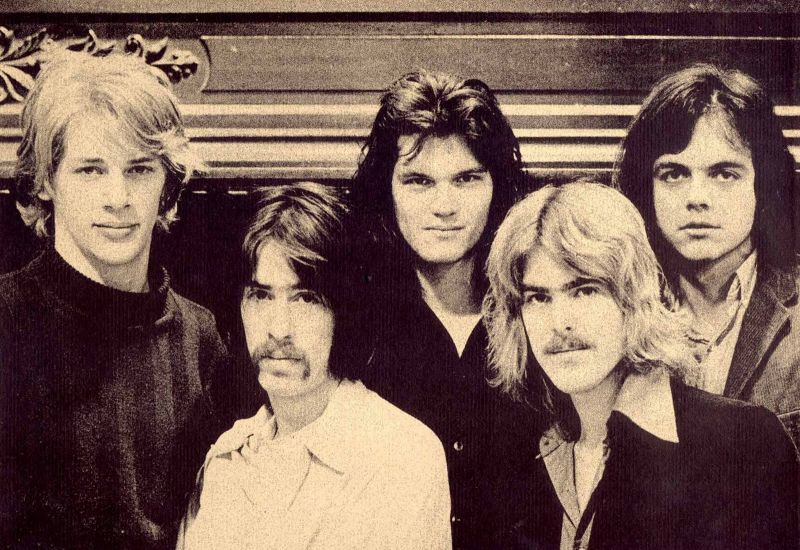

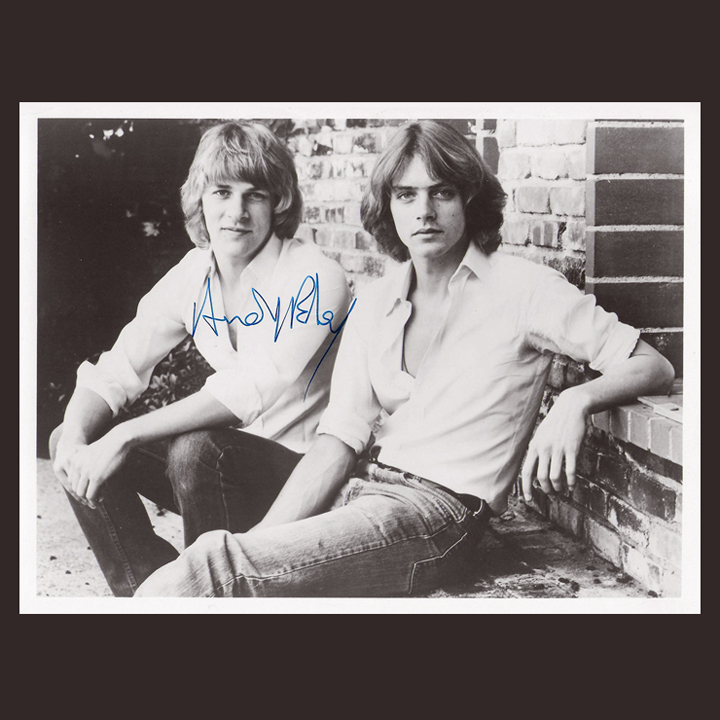

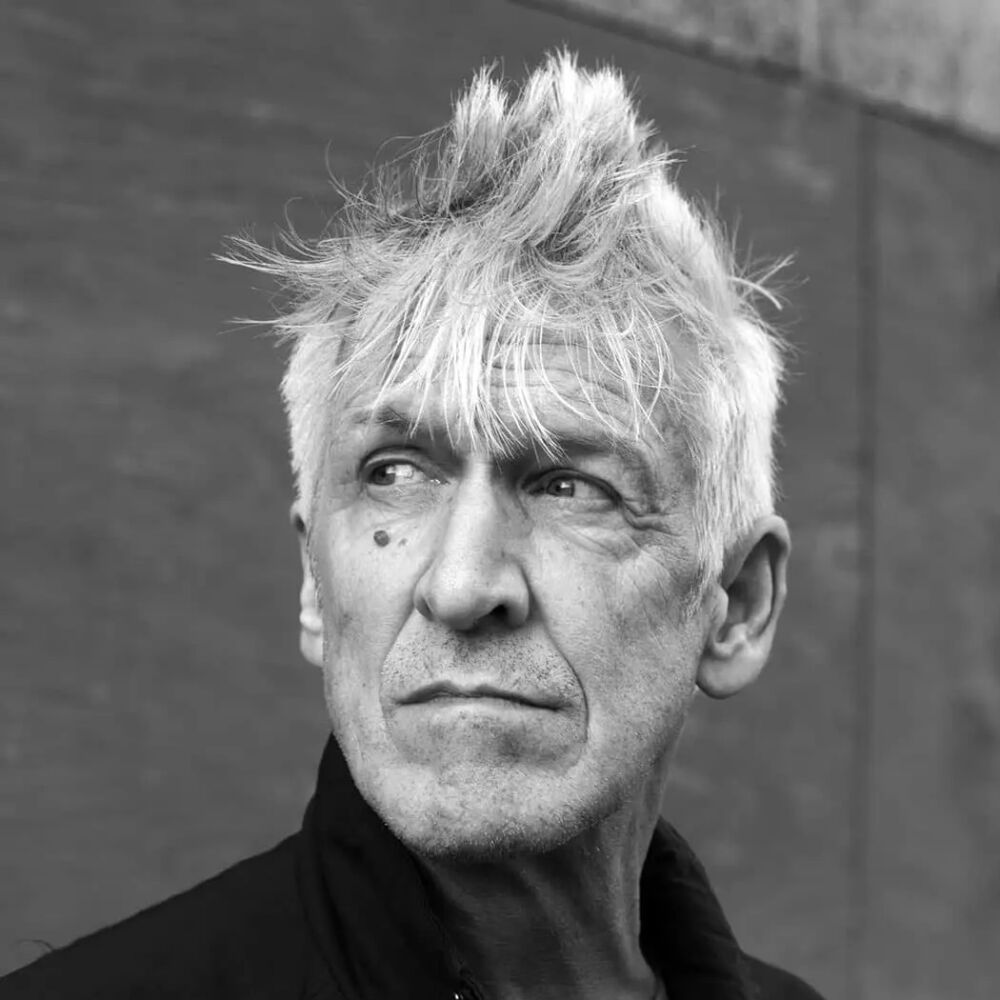

The group formed in 1969 as Catfish Black, a six-piece including three Harvard undergrads – Maine native Jimmy Mahoney on vocals, Wisconsin native Jerry Harrison on keyboards and Connecticut-raised bassist Ernie Brooks – plus lead guitarist Eric Rose, rhythm guitarist Mike Reed and drummer Andy Paley. When Mahoney left the band in 1970, Paley moved to the front on vocals and harmonica, replaced behind the kit by Henry Stern (brother of guitarist Mike Stern, formerly of Blood, Sweat & Tears).

Through appearances at Harvard and other area universities/colleges, The Boston Tea Party, Stonehenge Club and other local venues – and opening several times for Aerosmith before the soon-to-be legends signed their first recording contract in 1972 – Catfish Black built an enthusiastic local following. Their repertoire was a mix of revamped covers and fine-tuned originals (most penned or co-written by Paley) and the group served up a groovy gumbo of ear-catching harmonic hooks and eye-catching hippie hairdos.

SUZIE ADAMS, DEMO, EARLY LABEL INTEREST, FIRST LINEUP CHANGE

In late 1970, having established some solid street cred but without a record deal in sight, the band hired Suzie Adams, a Wellesley native studying at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, as their manager, which led to Marblehead-based promoters Neil and Loy Grossman requesting a demo that they could shop to labels. Inspired by the brothers’ possible industry contacts, in early 1971 the band recorded a gig at MIT’s Union Hall on a TEAC two-track but, although Janus Records showed some initial interest, neither audition invitations nor contract offers resulted.

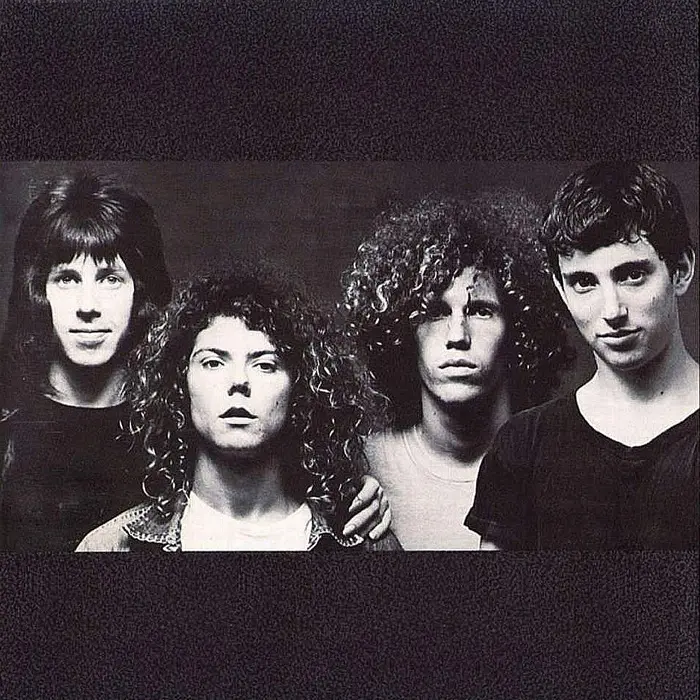

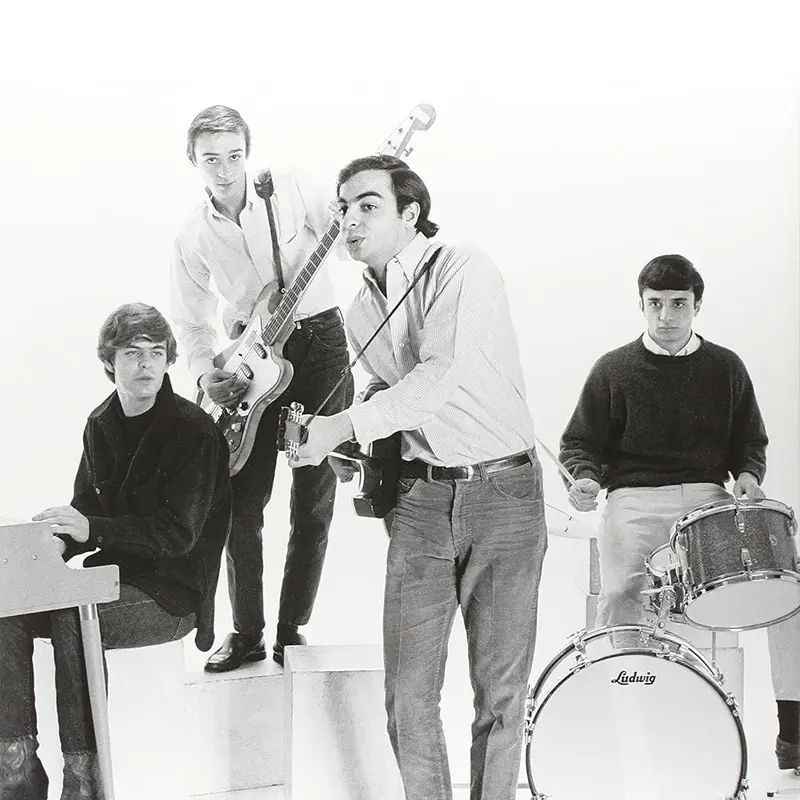

Adding insult to injury, shortly after the MIT show, bassist Brooks and keyboardist Harrison left to join The Modern Lovers (following the departures of John Felice and Rolfe Anderson), with Leigh Foxx replacing Brooks but nobody taking over for Harrison, downsizing Catfish Black to a five-piece. Interestingly, the first show The Modern Lovers had ever played, in September 1970, was as the opener for Catfish Black at the Cambridge YMCA.

MAX’S KANSAS CITY, BECOMING “THE SIDEWINDERS”

In mid-1971, some five months after the lineup change, the group’s prospects brightened enormously when Paley’s friend Richard Robinson – producer, radio host and husband of renowned rock journalist Lisa Robinson – landed them a residency at Max’s Kansas City in New York, the first band offered a regular spot at the hyper-hip hangout since The Velvet Underground in 1970. Before their debut at Max’s, the band changed its name to The Sidewinders – from a line in Roger McGuinn’s song “Chestnut Mare” – after learning that a New York band had a moniker very similar to “Catfish Black.”

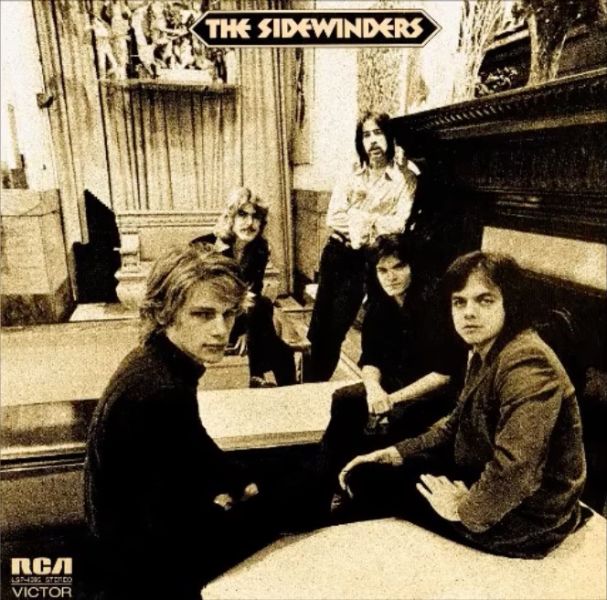

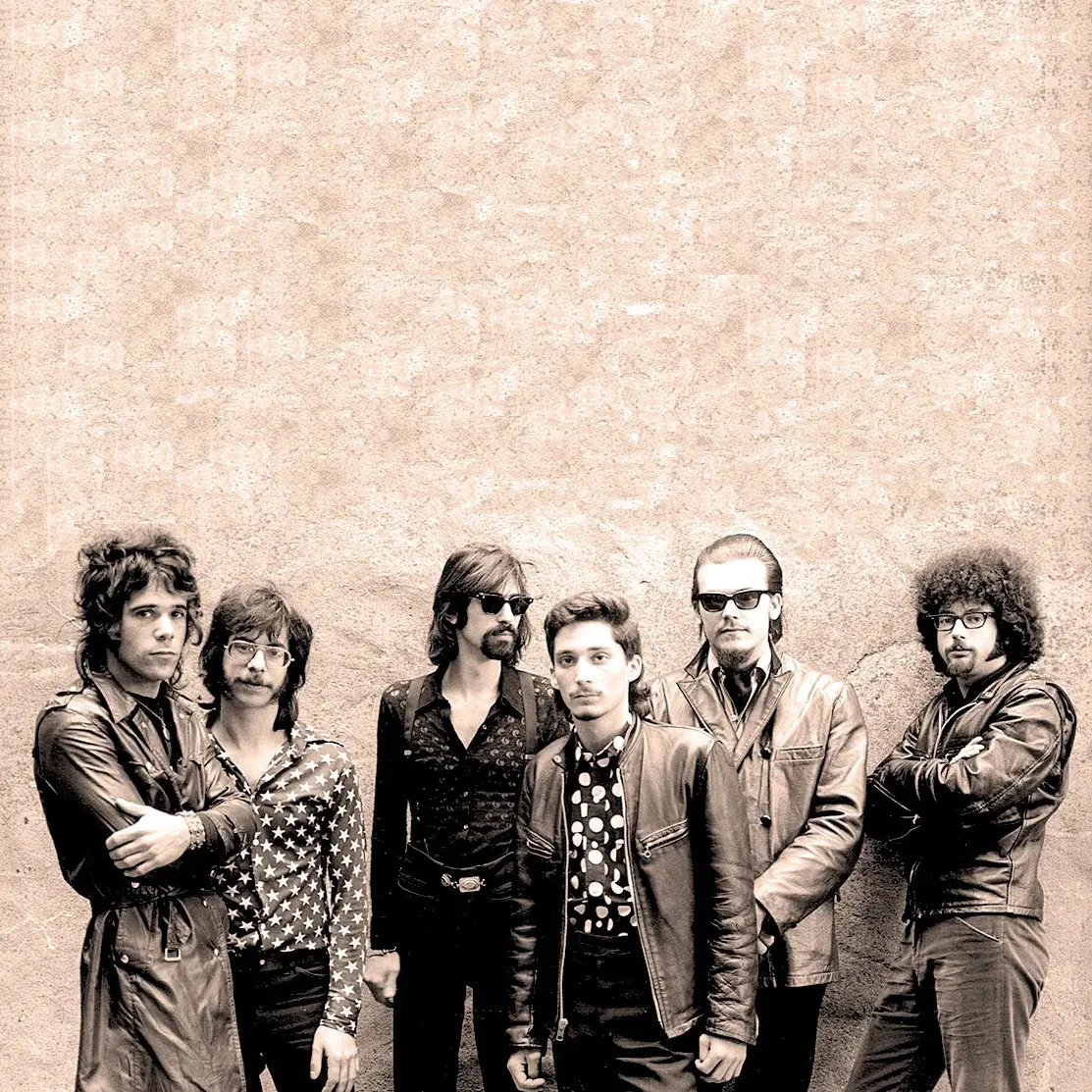

RCA SIGNING, DEBUT ALBUM, SECOND LINEUP CHANGE, BILLY SQUIER

After seeing The Sidewinders play at Max’s, RCA Records’ A&R exec Dennis Katz – who’d recently signed David Bowie, The Kinks and Lou Reed to RCA – signed them and arranged sessions, with Robinson as producer. One week before going into the studio with The Sidewinders, however, Robinson was sent to London to produce Lou Reed’s debut solo album and replaced by writer-composer-guitarist Lenny Kaye (later of Patti Smith Group). The result was The Sidewinder’s self-titled debut, an 11-track collection released in 1972 with 10 originals – three credited to Paley, two to Foxx and five to Paley-Rose – and a rendition of Russian composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestral interlude “Flight of the Bumblebee.”

Limited airplay and even more limited sales belied the glowing reviews in Circus, Creem, Variety, Rolling Stone and Billboard, the last of which made the LP their Pick of the Week. Still, while the album sold surprisingly well in Texas, it fared less well on both coasts and was a financial flop. Though Boston-based critic Joe Viglione applauded the songwriting, particularly Paley’s “Rendezvous,” and called Rose’s and Reed’s guitars “a perfect setting for Paley’s voice,” he also wrote that the group seemed to be emulating The Remains to a fault and “should’ve been putting some Kinks riffs into this material” instead.

Soon after the album hit the shelves and most copies sat gathering dust, Reed and Stern quit the group, replaced by keyboardist Larry Luddecke and drummer Brian Chase. At the end of 1972, Luddecke left, making The Sidewinders a Paley-Rose-Foxx-Chase quartet, but diminishing crowds and no label interest led the group to start auditioning potential second guitarists.

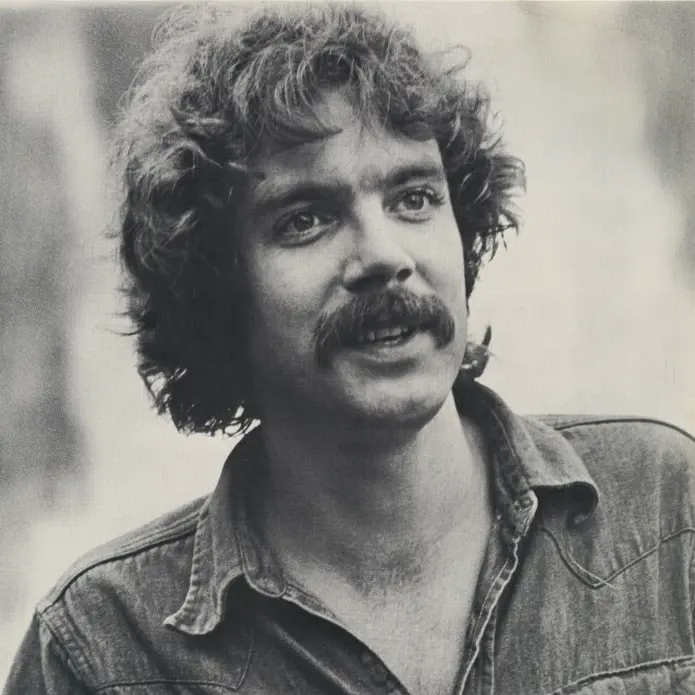

Billy Squier, a Wellesley native like Sidewinders’ manager Suzie Adams, got the gig, joining the band in early 1973. A ferocious guitarist with a classic-rock voice who’d played in The Tom Swift Electrical Band (house band at The Psychedelic Supermarket), New York-based Magic Terry & the Universe and attended Berklee College of Music, he seemed to be the perfect choice to revitalize the group. Reality proved otherwise, however, and for any number of reasons – fatigue, lack of a record deal, claims that Squier tried to commandeer the band – The Sidewinders veered further off the public’s (and the labels’) radar. A frustrated and exhausted Adams promoted the group to top talent agencies but all the key players – including the man who signed them to RCA, Dennis Katz (who’d become Led Zeppelin’s US agent) – turned her away.

DISBANDING, POST-SIDEWINDERS ACTIVITY

In mid-1973, Rose left the band and The Sidewinders unraveled for the remainder of the year before calling it quits. Rose and Foxx went on to play with The Paley Brothers and many others, Luddecke joined Skyhook (featuring vocalist George Leh), toured with various acts including Jonathan Edwards and spent four years as the musical director for Tom Rush’s band before forming Arlington-based studio Straight Up Music in 1978.

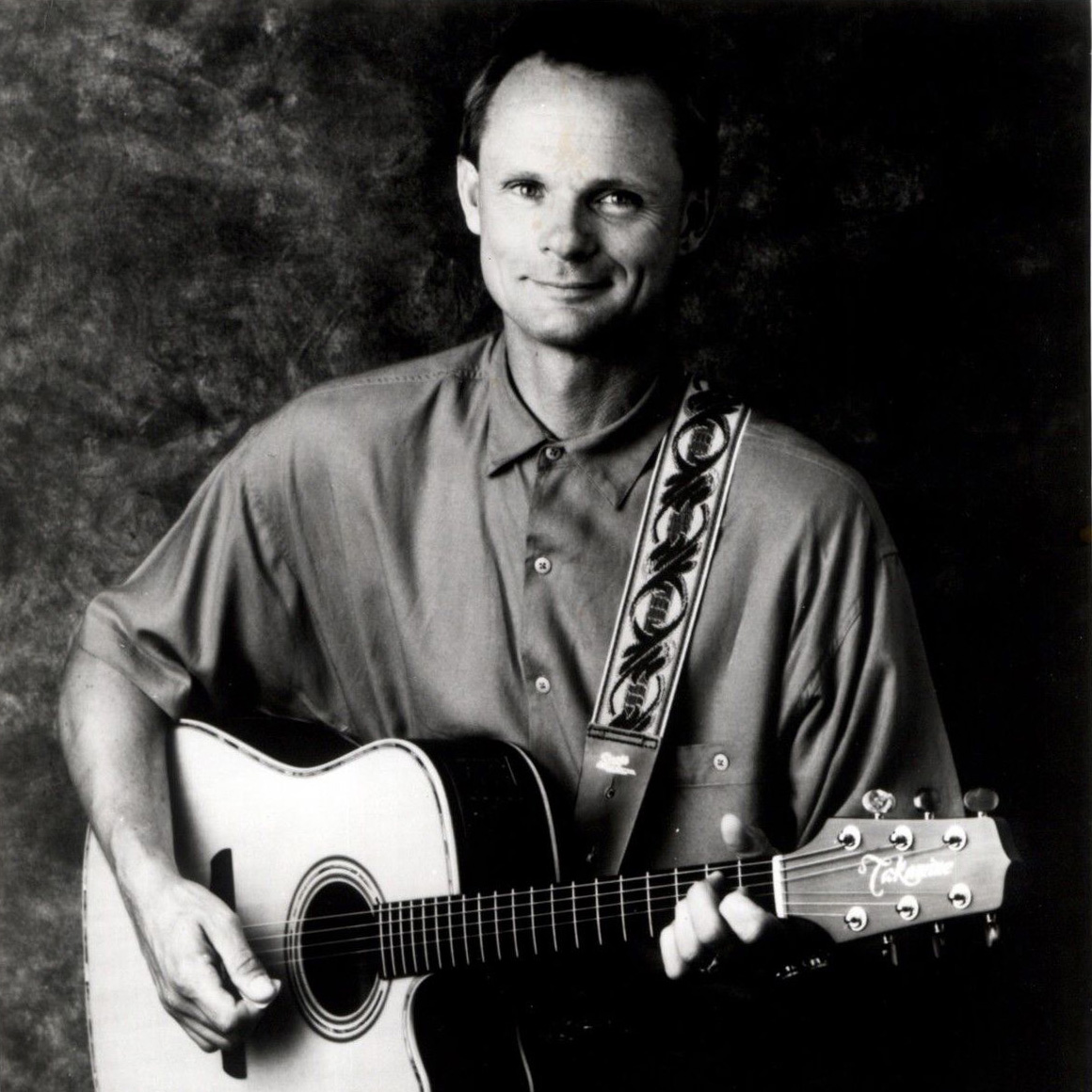

Paley, while recording and touring with his younger brother Jonathan as The Paley Brothers from 1974-79, recorded with Elliot Murphy, Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers and Nervous Eaters and toured with Patti Smith Group before he became a high-profile producer for Brian Wilson, Jerry Lee Lewis, NRBQ and a host of others. He also composed the scores for a number of hit TV shows, including Nickelodeon’s SpongeBob SquarePants, in the decades before his death in November 2024. Squier joined Piper as lead vocalist/guitarist in 1976 and made two critically acclaimed albums with the group before going solo in 1979. In 1981, his solo album Don’t Say No produced three US hit singles, “In the Dark” (#3),“Lonely is the Night” (#28) and – as anyone who listened to American FM radio or watched MTV in the 1980s knows – “The Stroke” (#3).

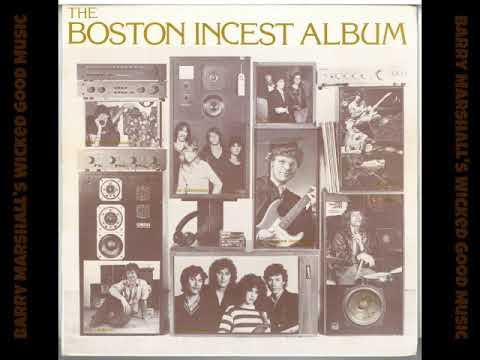

THE BOSTON INCEST ALBUM, “STREETWALKER”, LEGACY

In 1980, Sounds Interesting Records issued The Boston Incest Album, a 14-track compilation featuring the previously unreleased Sidewinders song “Streetwalker” (with Squier on guitar and backing vocals) and material by The Marshalls, Willie “Loco” Alexander and The Baboon Band, The Peytons, Christen and The Notes, The Fugitives, Erik Lindgren, Professor Anonymous, The Reflectors, Lynch and The Mob and Eric Rose.

Commenting on The Sidewinders’ legacy for AllMusic, critic Viglione framed it in the context of Boston’s early-‘70s scene: “The Modern Lovers were the essential punk band, Orphan with Jonathan Edwards were the folkies, and J. Geils had the blues market, leaving the most commercial sound to The Sidewinders.”

And, like Carter Alan calling them “a band that could have been God, but wasn’t,” that’s not damning with faint praise.

(by D.S. Monahan)