The Celebrity Club

The Celebrity Club in Providence, Rhode Island, was open for just 11 years and closed over 60 years ago, but its legacy has echoed across the decades like that of few other long-gone venues. And that’s not because it hosted a gaggle of jazz greats in the 1950s (and a few R&B/rock ones); plenty of other New England venues did the exact same thing at the exact same time. Most significantly, the Celebrity Club was important on a sociocultural level: It was a leader in the battle for racial equality when New England was, for all intents and purposes, just as segregated as the American South, not through Jim Crow laws but by ingrained prejudices and institutional barriers.

While it was not the first racially integrated venue of its kind in New England – both Wally’s Paradise (now Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club) and The Hi-Hat in Boston had been hosting multiracial audiences for at least a year before the Celebrity Club opened – it was the first nightclub in the Ocean State to welcome people of all skin tones. And by presenting world-class performers in a colorblind setting, it rapidly became Providence’s premier jazz joint and a symbol of substantial progress in race relations.

“Bohemians associated with the Rhode Island School of Design and the insular crowd of the East Side hipster connected in large and small ways with the African community for the first time, thanks to the Celebrity Club and its clones,” wrote saxophonist-percussionist Jason McGill in the quarterly Rhode Island History in 2005. “That helped spawn and define such phenomena as the local civil rights movement and the reactionary backlash it came to face.”

PAUL AMERICO FILIPPI

The Celebrity Club was founded by Paul Americo Filippi, an Italian-American Providence native born in 1914 who loved jazz and was keen to leave his mark on the segregated city. Prior to opening the club at age 35, he worked as a doorman at the Crown Hotel on Weybosset Street.

A dapper man known for his cordial personality, infectious enthusiasm and remarkable ability to remember names and faces, Filippi saw improvements in race relations as critical to his hometown’s development. And by acting on his convictions – boldly, despite frequent harassment by police and damage to his reputation among his white contemporaries – he became a man ahead of his time, a visionary impresario who publicly championed equality 16 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

OPENING

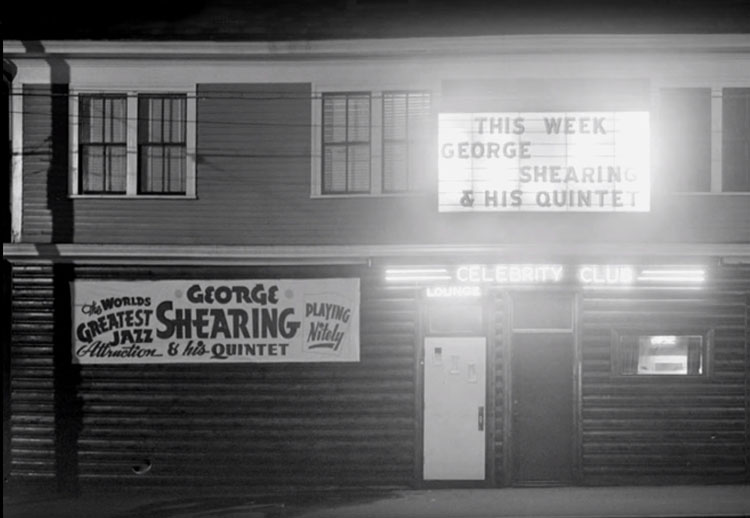

The Celebrity Club opened on November 18, 1949, at 52-54 Randall Street in the Randall Square neighborhood, on the western edge of Lippitt Hill. Since at least the 1920s, Providence had attracted nationally popular jazz combos and big bands – it was a convenient stop between New York and Boston – but before the Celebrity Club opened, nonwhites in the city who wanted to hear live jazz had to cram into Black-owned bars and speakeasies (known as “buffet flats” in African-American communities); other venues didn’t allow “coloreds,” to use the parlance of the era, unless they were playing in the band.

Filippi said he opened the club specifically to address that kind of inequality. “I came from a poor background and used to work on WPA projects with other poor people, and many of them were Black,” he told The Providence Chronicle in 1949. “One Black guy and I were talking one day and he said he was going to take his wife to dinner at some chicken shack in Boston…Well, that gave me an idea. I figured I’d open a place where Black people could go – a nice, small supper club where they could have a good time.”

“I’ll never forget the first night,” Filippi said of the 1949 opening in the 1982 independent documentary Oh, How We Danced. “White fella comes over and sat at the bar…He called me over and said, ‘You’re the owner?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘My wife and friends are in the car. Is it alright if we come in?’ We were breaking down all sorts of walls, and doing a good job of it too, if I may say so.”

INSTANT SUCCESS, POLICE RAIDS

Though the interior decorating was not finished in time for the opening, the capacity crowd of around 100 appeared not to notice as they listened to what Jason McGill wrote were “the sounds of the first of innumerable jam sessions featuring some of Providence’s finest jazz talent.” Within a few months, crowds had grown to around 300 and the Celebrity Club had established a reputation as a “musician’s paradise,” wrote Yuanyuan Dai on the smartphone app Rhode Tour, adding that “people from all over New England poured into this Randall street house of big-name bands.”

But praise for the club was anything but unanimous; some white Providence residents perceived it as a major threat to the status quo from which they had benefited for decades, and among those people were some of the top brass in law enforcement. The Providence police raided the Celebrity Club multiple times, harassing and sometimes arresting patrons, primarily Black ones. White people were usually told to “go home,” said saxophonist David Hector in 2001, but “colored folks were searched, put in paddy wagons and beaten.”

“One night they raided the place, dragged all the whites down to the police station and held them for two hours,” Filippi once recounted to The Providence Journal. “I was told that if I ‘kept the whites out,’ I’d be left alone. The funny thing was that when they let those people out of the police station [later that night], they all came right back to the club!”

There were several high-profile raids in 1954, but only four of the 125 people taken in for questioning were charged with a crime. The biggest raid came in January 1955, when cops reporting to Detective Commander Walter E. Stone detained 85 people for alleged possession of narcotics. All were released from custody several hours later without charge. According to reports in The Providence Journal, police also harassed patrons at two establishments that Filippi and his brothers opened in 1954, Filippi’s Café (at 18 Ashburton Street) and Club Downbeat (at 1049 Westminster Street).

NOTABLE APPEARANCES

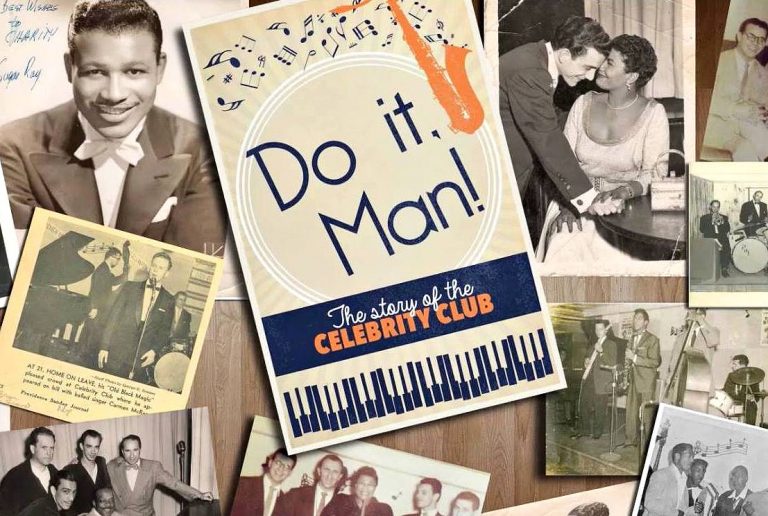

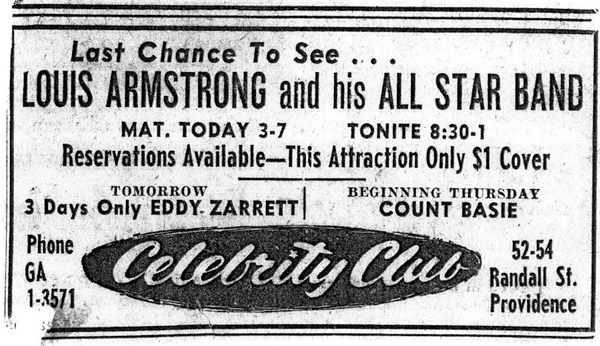

Ranked by jazz magazine Metronome as one of the top five live-music venues in North America in the early ‘50s, the Celebrity Club presented a who’s who of jazz giants during that decade including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughn, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Jordan, Erroll Garner, Coleman Hawkins, Stan Getz, Cootie Willliams, George Shearing and Sammy Davis Jr.

In 1951, The Providence Chronicle ran a story about a tall, handsome stranger who sang to some neighborhood kids one afternoon before his show at the Celebrity Club that night. His name was Nat King Cole; the song was “Mona Lisa,” which spent five weeks at #1 in the Billboard singles chart in 1950.

While the club was focused on jazz, it hosted several R&B greats including Ray Charles and first-generation rock ‘n’ rollers like Fats Domino. In January 1955, seven months after their rendition of “Rock Around the Clock” hit #1 in the Billboard singles chart, Bill Haley and His Comets played a seven-night stand.

LOCAL ARTISTS BENEFIT

Filippi’s knack for drawing major stars to the Celebrity Club allowed a number of local musicians to work as their sidemen, which sometimes launched their careers to new heights. Among them were pianist Dave McKenna (Woody Herman, Rosemary Clooney), trumpeter Bobby Hackett (Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman), saxophonist Paul Gonsalves (Duke Ellington, Count Basie) and vocalist Carol Sloane (Larry Elgart, Kenny Burrell).

Without exception, even the biggest names on the Celebrity Club stage were unable to stay in local hotels if they were Black – staff would lie about being “fully booked” – so they stayed with area residents. In an odd and unintended way, these living arrangements benefited some younger musicians because occasionally the heroes who were staying in their homes gave them musical guidance.

CLOSING

By the mid-1950s, high taxes and the amount of revenue lost from police raids had become a major problem and the club was beginning to struggle. “I’d get someone like Ellington to come here directly from a command performance for the Queen of England, and what would happen?” Filippi said in 1982. “He’d have to put up with being frowned upon by two-bit politicians and cops. It was a shame.”

Another factor contributing to the club’s gradual demise was the changing face of American popular music starting in the mid-‘50s, when jazz started taking a back seat to rock ‘n’ roll on the radio. A third factor was increased competition from newly opened clubs, which made it more difficult for Filippi to attract top talent.

In 1958, Filippi sold the Celebrity Club, turning his attention to a property he’d bought in 1956, Ballard’s Beach Resort on Block Island. The club survived for another two years under its new ownership, then closed for good in 1960. The building was empty until 1963, when it was demolished as part of the massive urban-renewal project that displaced both the Randall Square and Lippett Hill communities. Filippi passed away on June 6, 1992, at age 78.

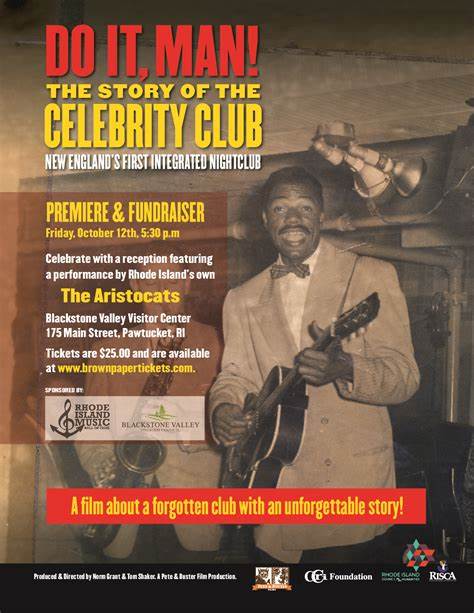

DO IT, MAN! DOCUMENTARY

In 2018, the documentary Do it, Man! premiered. Put together by jazz historian Tom Shaker and videographer Norm Grant, the film presents the Celebrity Club’s storied history through rare footage and commentary by local legends including Rhode Island Radio Hall of Famer Steve Kass, who was club’s emcee, drummer Duke Belaire and vocalist Clay Osborne. The film won the Peter C. Collins Best Documentary award from the Popular Cultural Association.

The title Do It, Man! comes from the time Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame double bassist Bob Petteruti played with Duke Ellington’s orchestra at the Celebrity Club when Ellington’s bassist didn’t arrive on time. “The Duke asked, ‘Would you sit in for him?’” said Petteruti, who was playing in the band that opened for Ellington that night, in 2005. “’No,’ I replied, ‘I can’t do that. I’m not good enough to play with you.’” When Ellington insisted, one of Petteruti’s bandmates said, “Do it, man!” And he did.

LEGACY

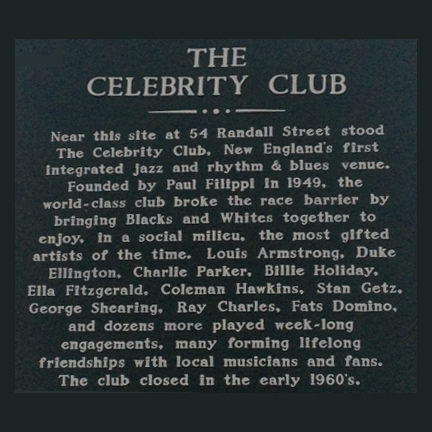

The only reminder of the Celebrity Club today is a plaque erected in 2013 by the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society that sits, rather obscurely, on a traffic island near its former location, on the east side of the Orms Street Marriott (at the intersection of Charles and Ashburton Streets). The state of Rhode Island has never officially recognized the club.

Asked in 2019 about his father’s accomplishments, Filippi’s son said he helped ease the racial tensions of the era. “He had the who’s who of American musical history,” said Blake Filippi, now the minority leader in the Rhode Island House of Representatives. “Organically, [the Celebrity Club] became integrated. The white community saw these musicians and wanted to participate.”

Asked in 1982 about his own thoughts on his accomplishments, founder Paul Filippi was as modest as any former venue owner has ever been. “My club was able to go on for a good number of years,” he said. “But like all good clubs, they have their day, they have their time, and they wear themselves out.”

(by D.S. Monahan)