The Ark

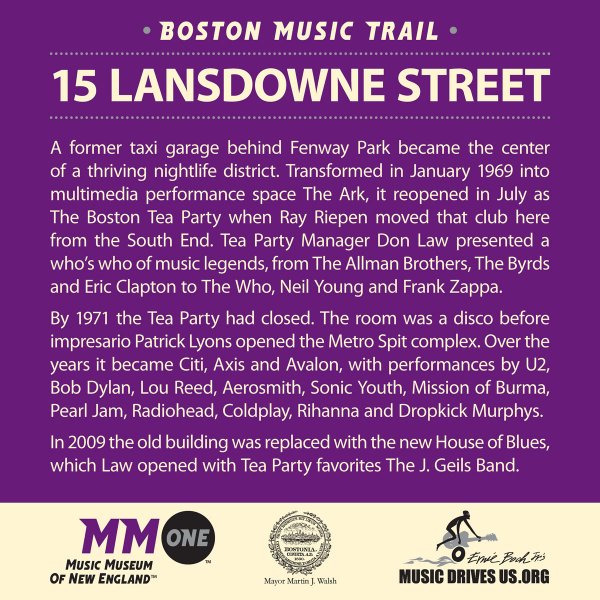

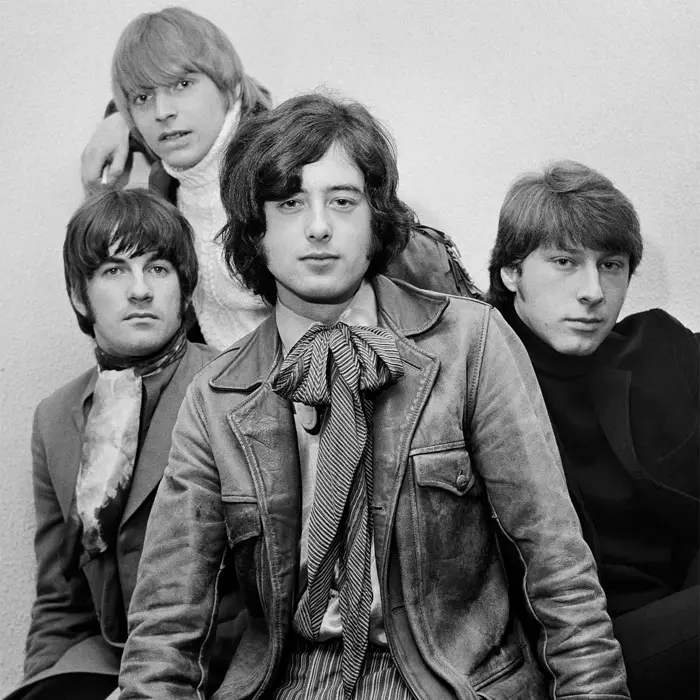

At the end of 1968, The Boston Tea Party was the epicenter of the city’s rock, R&B, blues and soul scenes, having presented a slew of locally, nationally and internationally acclaimed acts since opening in January 1967, among them The Lost, The Hallucinations, Howlin’ Wolf, The J. Geils Band, John Lee Hooker, The Velvet Underground, The Chambers Brothers, The Who, Jeff Beck Group, The Yardbirds, Van Morrison and B.B. King. Though the 720-seat club faced competition from smaller spaces like Paul’s Mall, Psychedelic Supermarket, The Unicorn Coffee House, The Sugar Shack and The Crosstown Bus, no other venue in the area, including Boston Garden, boasted as dizzying an array of talent as the Tea Party did at its 53 Berkely Street location.

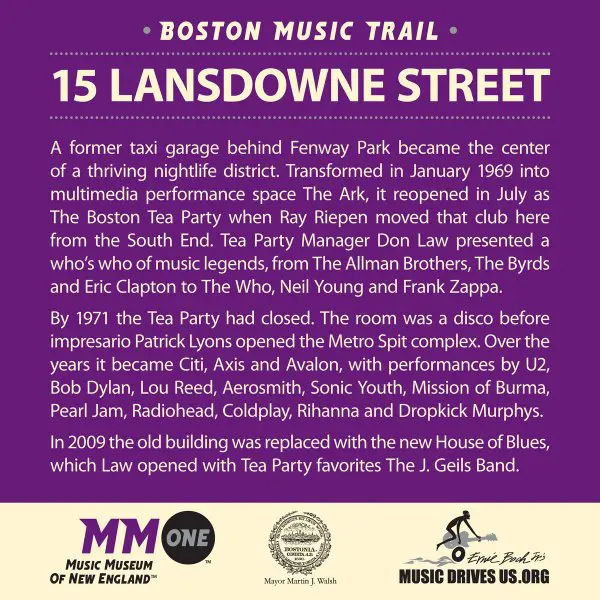

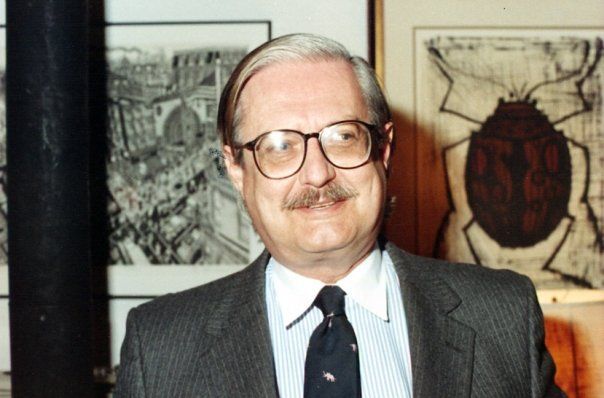

But in late January 1969, rookie promoter Charles Thibeaux and 17 investors opened a rival club at 15 Lansdowne Street that held more than double the Tea Party’s capacity and was just a mile and a half away from the powerhouse venue: The Ark. And though the 1,700-seat space was open for less than six months before it merged with the Tea Party at the 15 Lansdowne location, it hosted an impressive collection of established rock, R&B, soul and blues acts, several later-famous local artists and helped establish Kenmore Square as the nightclub nexus that it remains to this day.

OPENING, FINANCING

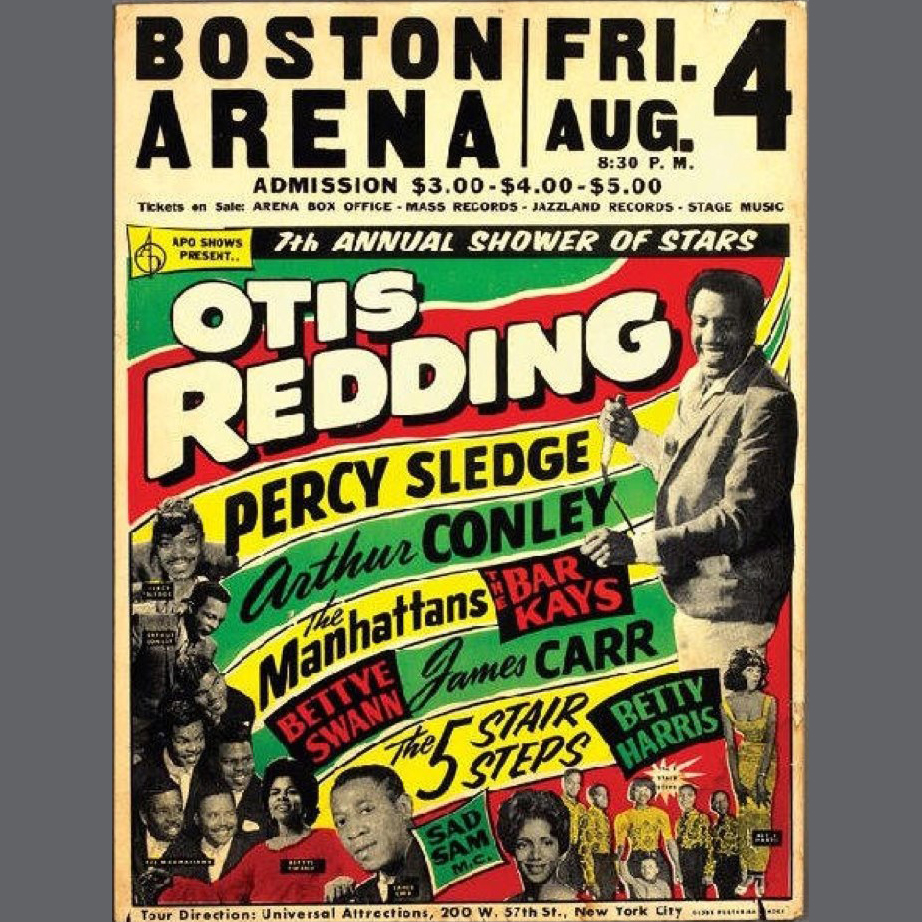

The Ark opened on January 24, 1969, a Friday, and the headliners were the Los Angeles-based band Spirit and Otis Redding’s longtime backing band The Bar-Kays. Though the event was preceded by a $3,500 champagne party attended by an estimated 3,200 people, it was largely overshadowed in the press by Led Zeppelin’s show at the Tea Party that night, the second concert of a four-night stand supporting their newly released debut album.

The opening was a risky venture for two reasons: first, no other city in the US, including New York, had two mid-sized venues that brought in internationally renowned rock acts (according to a June 1969 article by Gregory McDonald of The Boston Globe); second, Tea Party managers Don Law and Steve Nelson had established very close relationships with American and English touring bands. On the other hand, Boston’s appetite for rock was voracious, as confirmed by WBCN’s successful shift from a classical format to an all-rock one in the spring of 1968, and the area’s massive student population guaranteed that those tastes would not change any time soon.

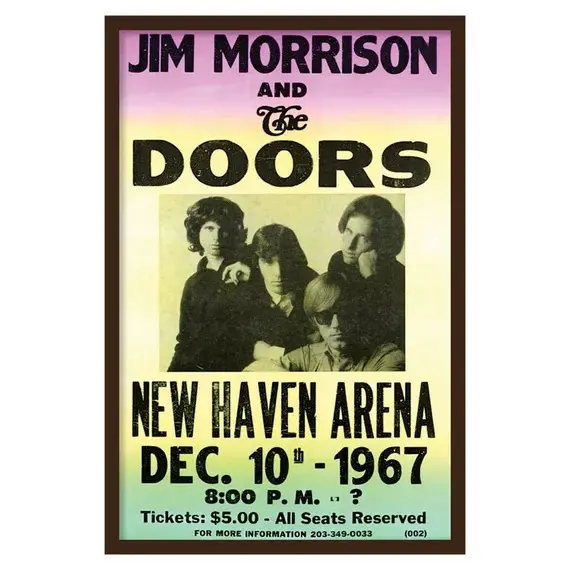

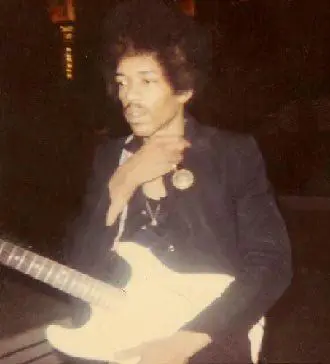

Furthermore, The Ark was extremely well financed. Whereas the Tea Party’s original owners, Ray Riepen and David Hahn, had capitalized their club with a mere $850 (about $8,000 in 2024), The Ark’s stockholders invested $350,000 (about $3 million in 2024) to construct and incorporate theirs, according to McDonald, who wrote that the investors included “local doctors, university people and businessmen.” The amount of capital was a significant factor when The Ark opened because popular acts were demanding substantially higher fees than when the Tea Party opened two years before; The Doors and Janis Joplin fetched up to $15,000 per night (about $128,000 in 2024) and clubs paid The Jimi Hendrix Experience as much as $25,000 (about $214,000 in 2024).

DESIGN, ENTERTAINMENT ROSTER, STAFF

The Ark differed from the Tea Party in several ways besides capacity and start-up capital, all of which made it a unique space, not a copycat. First, unlike the single-room Tea Party, the venue was spread across three levels and featured multiple entertainment areas, like New York City’s Electric Circus, so rock acts were just one part of an evening that included dancing, drinking and socializing far from the stage. “The major emphasis at The Ark is on creating an elaborate and stylized fantasy environment, with the music as more a contributing than dominating factor,” wrote Salahuddin I. Imam in The Harvard Crimson in February 1969. Second, while the Tea Party provided a much more intimate atmosphere than The Ark, the latter offered a genuine multimedia experience; every wall was covered with computerized light shows of various themes and included pictures ranging from Janis Joplin to Egyptian hieroglyphics while the state-of-the-art sound system allowed for “definite variations in texture (depending on where you are in the building),” according to Imam.

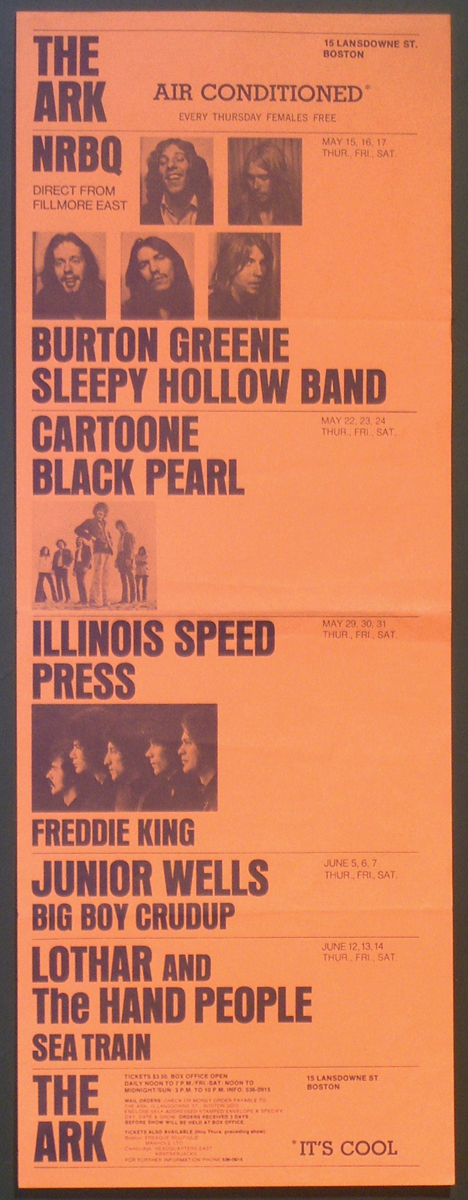

Other distinguishing factors were The Ark’s entertainment roster and number of staff. Unlike the music-focused Tea Party, The Ark usually presented bands on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays only and non-musical events such as The Bread and Puppet Theatre, San Francisco Mime Troupe, Xenogenesis and The Living Theatre on other nights. In terms of employees, while the Tea Party had just three full-timers and depended on music-loving volunteers for pre-show prep, ushering and after-concert clean up, The Ark had 10 full-time staff and 16 part-time ones.

NOTABLE APPEARANCES

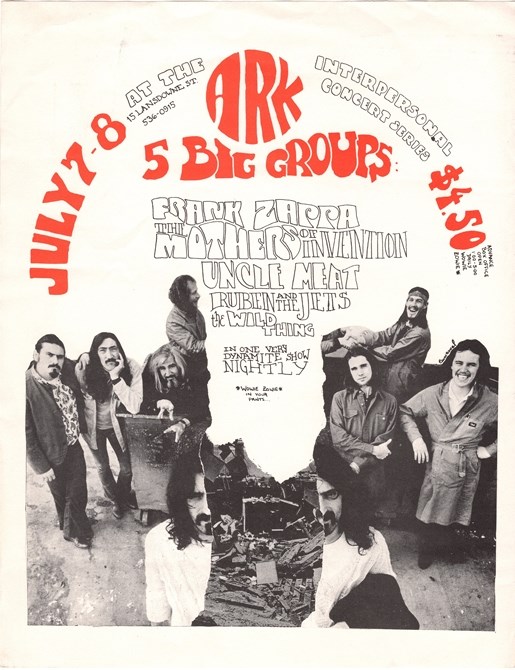

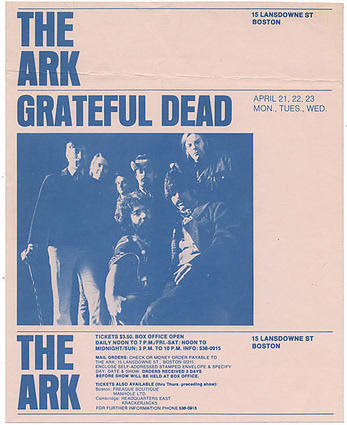

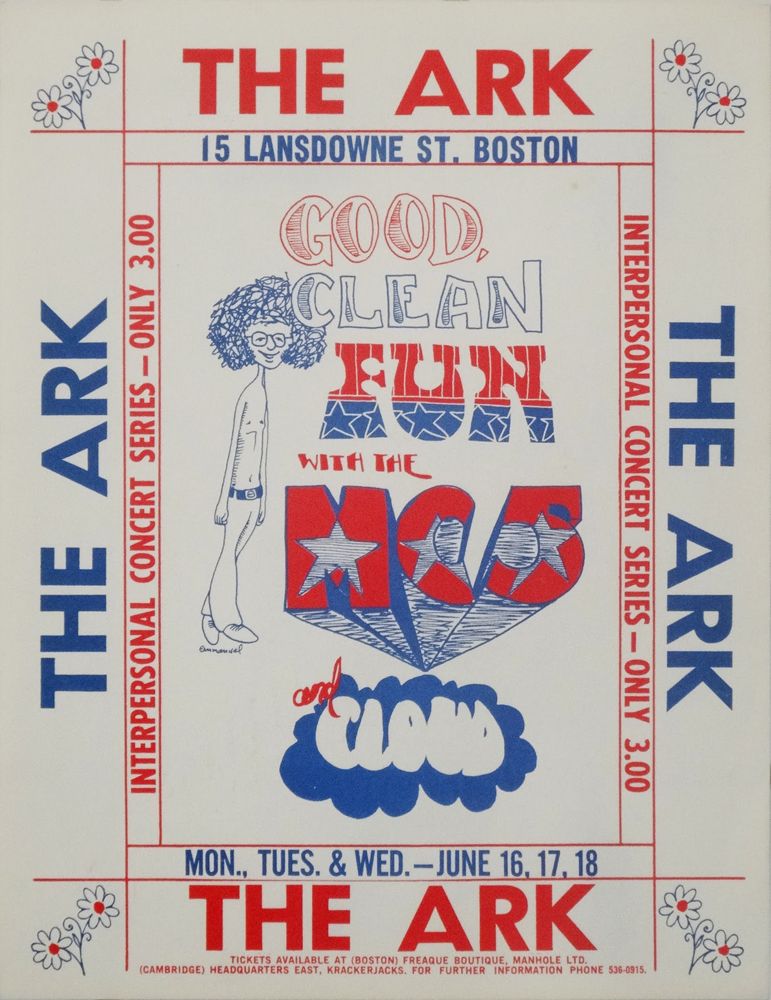

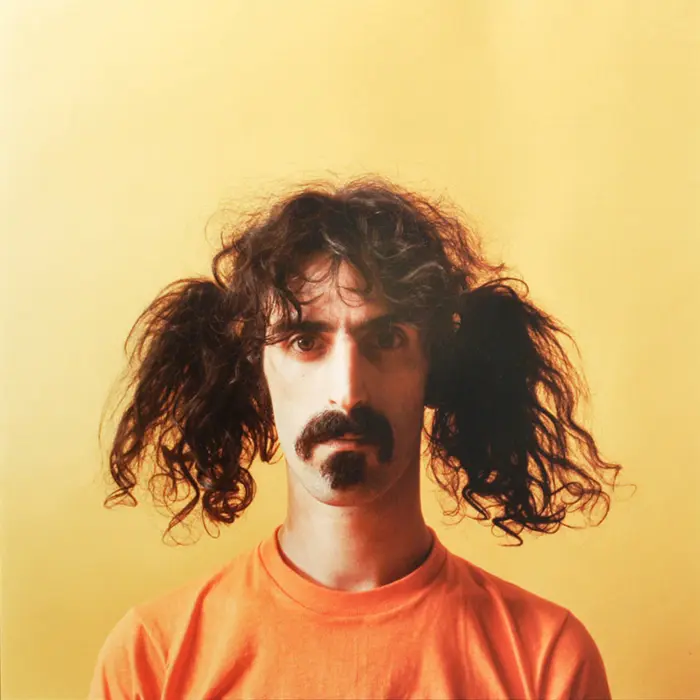

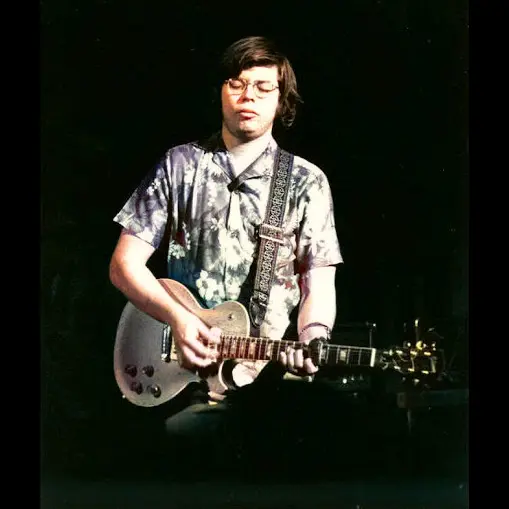

After Spirit and The Bar-Kays headlined the debut event, The Ark presented an eclectic assortment of well-known and relatively unknown acts during its 23-week existence. Among the most prominent were The Flying Burrito Brothers (whose now-classic debut album The Gilded Palace Of Sin was issued the week of their appearance), Stax soul singer Eddie Floyd, blues guitarist Freddie King, harmonica legends Junior Wells and James Cotton, blues singer-songwriter-guitarist Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Michigan-based rockers MC5, vocal quartet The Four Freshman, Canned Heat (six weeks before their song “Going Up the Country” became Woodstock’s unofficial anthem), The Grateful Dead, Van Morrison and The Mothers of Invention.

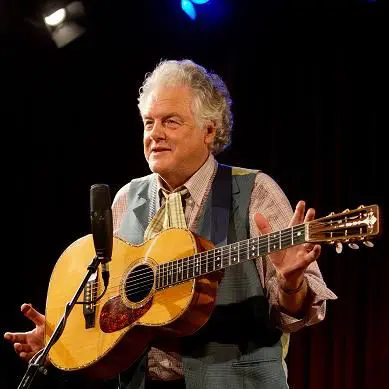

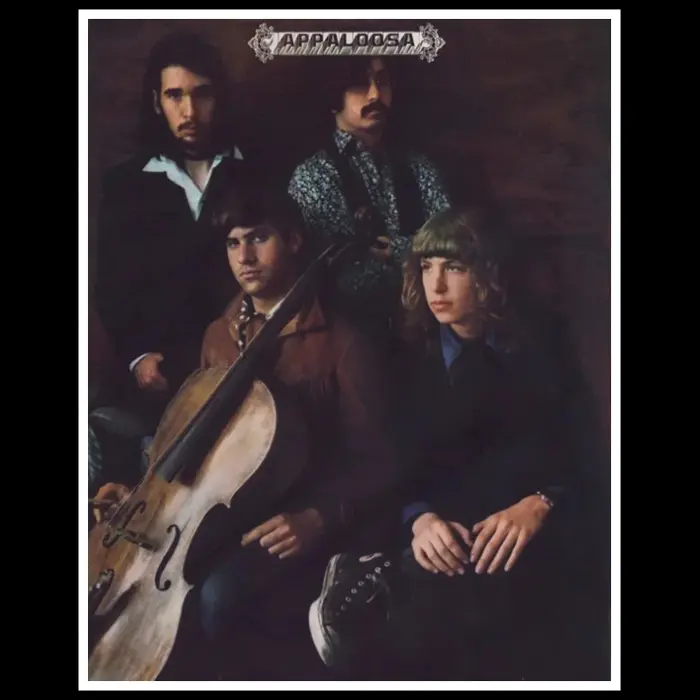

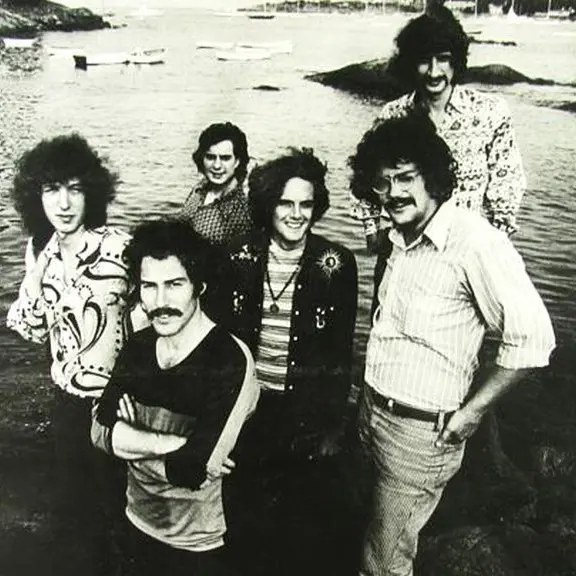

A wide variety of New England-rooted artists and bands appeared at The Ark, including Earth Opera (co-founded by Peter Rowan), Black Pearl (a spin-off of The Barbarians), NRBQ, Appaloosa, Seatrain and Fort Mudge Memorial Dump. In early April, about a week before Columbia released his third album, Giant Step / De Ole Folks Home, 27-year-old Taj Mahal took to the stage with a trio; later that month, roughly a year before he recorded his debut album, 24-year-old Chris Smither appeared solo.

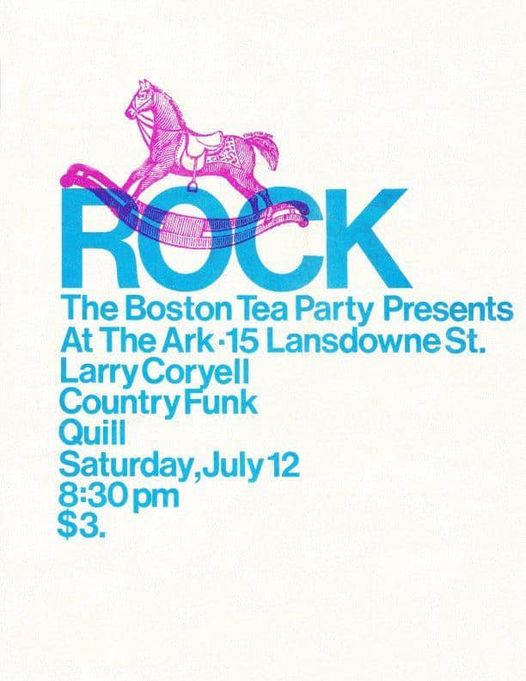

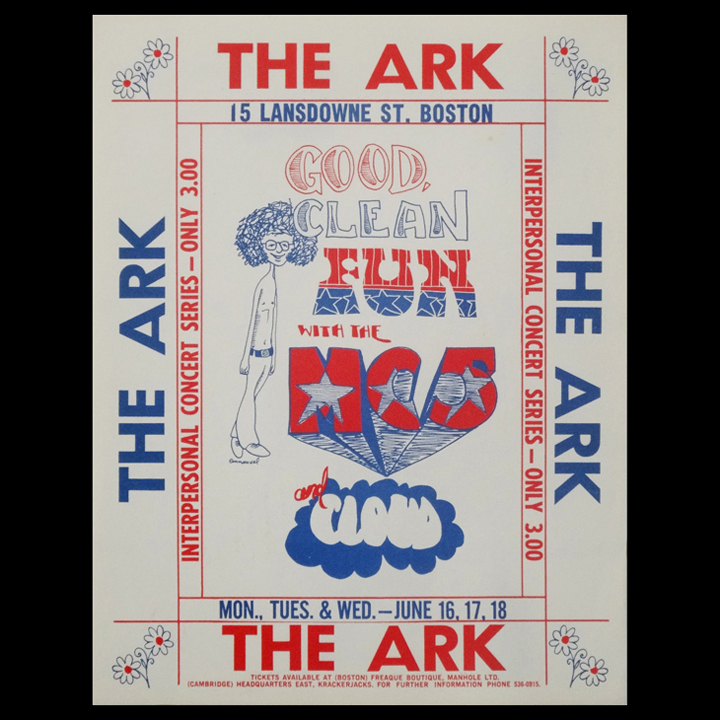

Other acts included folk duo Bunky and Jake, blues pianist Otis Spann, singer-songwriter John P. Hammond, bluesman Charlie Musselwhite, John Lennon’s future backing band Elephant’s Memory, Canadian rock outfit The Collectors, Greenwich Village-based Cat Mother & The All-Night Newsboys, Burton Greene & The Sleepy Hollow Band, Scottish rockers Cartoone, Cloud, The Illinois Speed Press, Lothar & The Hand People, Good Clean Fun, Kaleidoscope, Country Funk and English soul octet The Foundations (whose 1968 rendition of “Build Me Up Buttercup” hit #1 in the Cash Box 100 and Canada’s RPM chart and #2 in the UK Singles chart).

FINAL CONCERT, TEA PARTY MERGER, POST-TEA PARTY VENUES

On Saturday, July 12, 1969, The Ark and The Boston Tea Party merged at the 15 Lansdowne Street location; the headliner that night was jazz guitarist Larry Coryell. “The price of rock acts has risen so high that you have to have a hall of close to 2,000 capacity to afford them,” the Tea Party’s Riepen told The Boston Globe’s McDonald the week of the Tea Party’s move from its original Berkeley Street home. Though the venue’s was officially renamed The Boston Tea Party, many continued to refer to it as “The Ark” (in the same way that many in the San Francisco area did when referring to the Fillmore West as “The Carousel” long after promoter Bill Graham had taken over and renamed it).

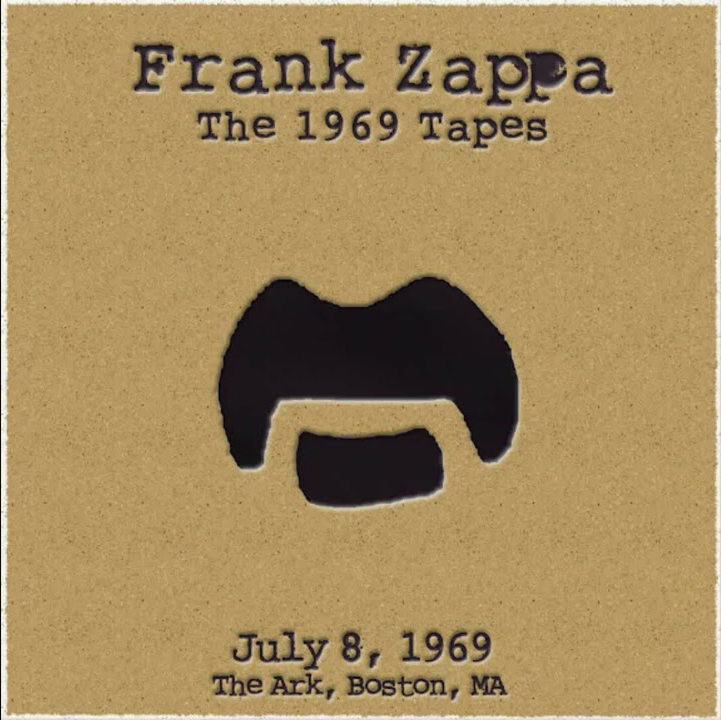

The final concert at the Tea Party’s original location was on July 11, headlined by The Velvet Underground, and the final one under The Ark marquee was on July 8, headlined by The Mothers of Invention. The Mothers’ appearance was bootlegged, but Frank Zappa officially released the tape in 1991, two years before his death, as Frank’s Mothers of Invention – The Ark. One track from the gig, “Baked Bean Boogie,” appeared on You Can’t Do That On Stage Any More, Vol. 5 (1992, Rykodisc).

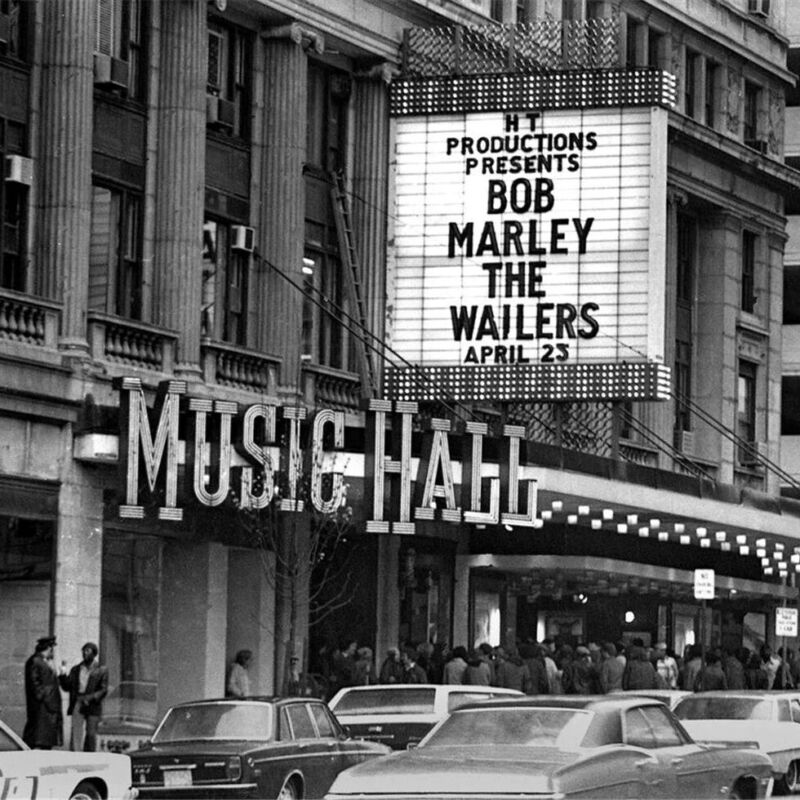

The Boston Tea Party remained open until December 1970, with Riepen being chairman of the operating entity (Environmental Arts Inc.), Ark founder Charles Thibeaux as the merged clubs’ chairman of the board and treasurer and Don Law as general manager. Following the Tea Party’s demise, the 4,400-capacity Music Hall – which transformed from a movie theatre in to a concert venue in August 1968 – became Boston’s premier mid-sized venue for rock, folk, roots, pop, R&B, soul and reggae until closing in 1980. By that time, the 2,700-seat Orpheum Theatre was well on its way to becoming Boston’s main mid-sized rock/pop venue, the 2,625-seat Symphony Hall had significantly expanded its non-symphonic offerings and the 1,227-seat Berklee Performance Center was hosting acts of virtually every musical genre ever invented.

(by D.S. Monahan)