Talkin’ Bob Dylan’s New England Back Pages

photo by Stephen M. Fenerjian

Ironically, since Bob Dylan’s exquisite use of language redefined songwriting, there are no turns of phrase quite eloquent enough to describe the scope of his influence on the craft. As his longtime friend and fellow Traveling Wilbury George Harrison once quipped, “Bob Dylan makes William Shakespeare look like Billy Joel.” Nor are there any easy ways to explain Dylan’s titanic impact on popular music; for untold millions of singers, songwriters, musicians and fans, the man born Robert Allen Zimmerman on May 24, 1941 is the epitome of creativity, courage, cleverness and cool.

And it’s arguable that such sentiment runs particularly deep among throngs of New Englanders. Dylan honed his craft in the region years before becoming a household name and has made hundreds of appearances in the six-state area, including the historic one at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 that redefined the parameters of folk and rock forever. Like Van Morrison, whose months living in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1968 were pivotal to his artistic development, Dylan’s singular place in New England’s musical back pages is as undeniable as his influence on American culture writ large.

FIRST NEW ENGLAND APPEARANCE, “BABY, LET ME FOLLOW YOU DOWN”

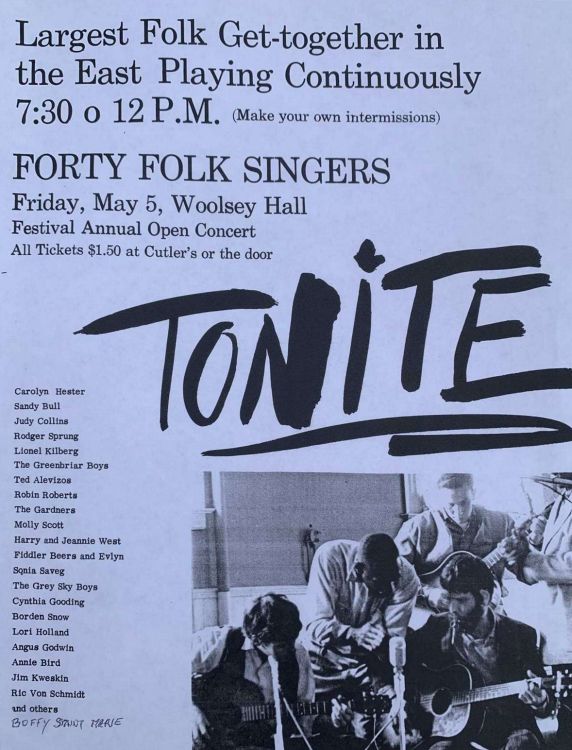

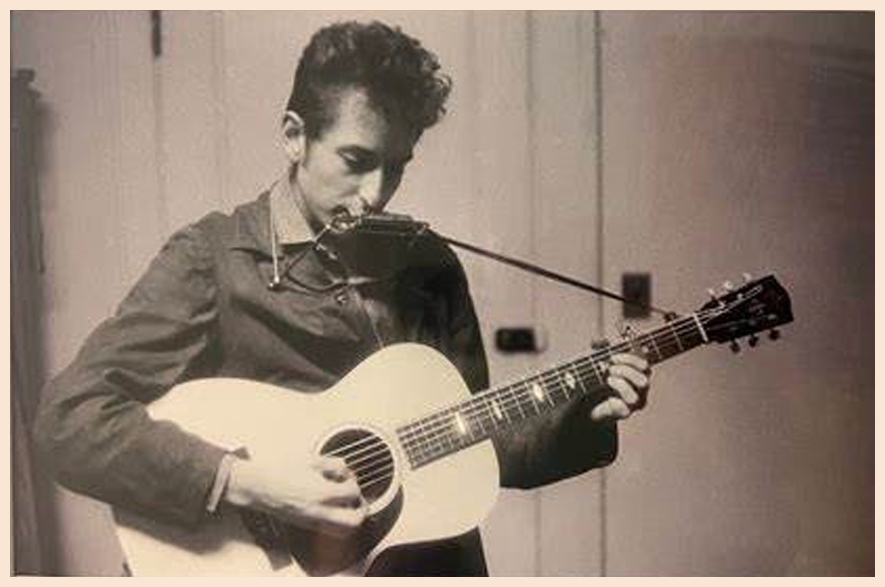

Dylan made his first New England appearance on May 5, 1961, three weeks before his 20th birthday, at Woolsey Hall in New Haven, Connecticut as part of the Indian Neck Folk Festival. The bill included two famous faces from the Boston/Cambridge scene, Jim Kweskin and Eric von Schmidt, and Dylan played a three-song set of Woody Guthrie covers (no originals): “Talking Columbia,” “Hangknot, Slipknot” and “Taking Fish Blues.” He played the same set the following night at Montowese House in Branford, also as part of the festival.

At that time, Dylan was “a complete unknown” without a recording contract, having moved to New York City from his native Minnesota just five just months before. In mid-September 1961, four months after the Connecticut shows, he signed with Columbia Records and in March 1962 the label released his self-titled debut album, which includes just two originals, “Talkin’ New York” and “Song to Woody.” The other 11 songs on the LP were written or arranged by folk-blues originators (Bukka White, Jesse Fuller, Curtis Jones, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Mississippi Fred McDowell) or traditionals arranged by Dylan or artists nearer to his own age (von Schmidt and Dave Van Ronk).

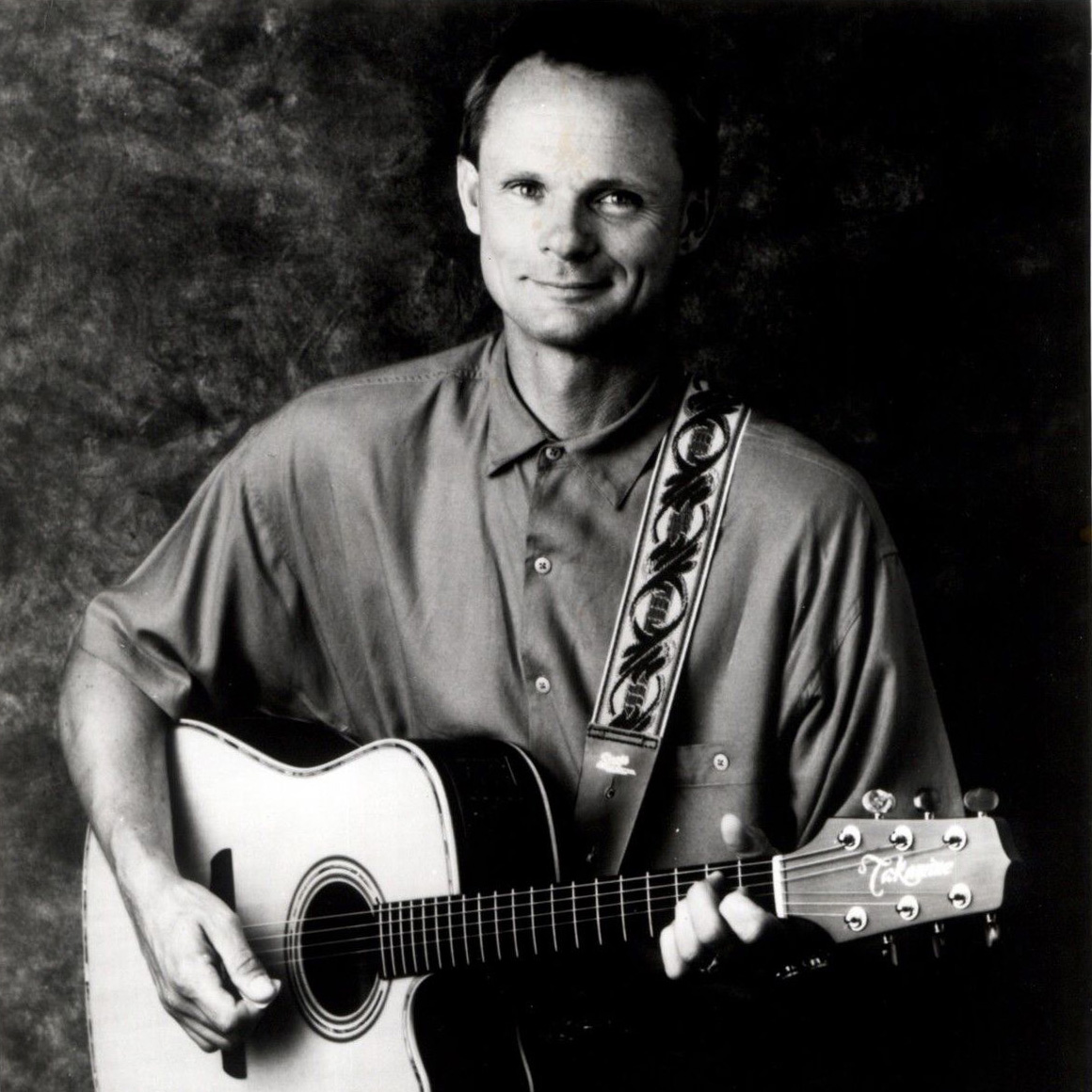

The debut disc includes his rendition of “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down,” which has a direct connection to New England: Bridgeport, Connecticut native von Schmidt arranged the song based on a Blind Boy Fuller tune and taught it to Dylan in late 1961 in Cambridge, according to von Schmidt’s obituary in The New York Times. Over the guitar introduction on the LP, Dylan says he “first heard this song by Rick von Schmidt” and that he “met him one day in the green pastures of Harvard University.”

“I sang him a bunch of songs and, with that spongelike mind of his, he remembered almost all of them when he got back to New York,” von Schmidt told The Boston Globe in 1996 about introducing Dylan, 10 years his junior, to what’s now a folk standard. The younger singer-songwriter made the song a staple of his setlist through the mid-‘60s; he played it in October 1965 when he appeared at the Back Bay Theatre in Boston.

OFFICIAL BOSTON DEBUT, “BLOWIN’ IN THE WIND”

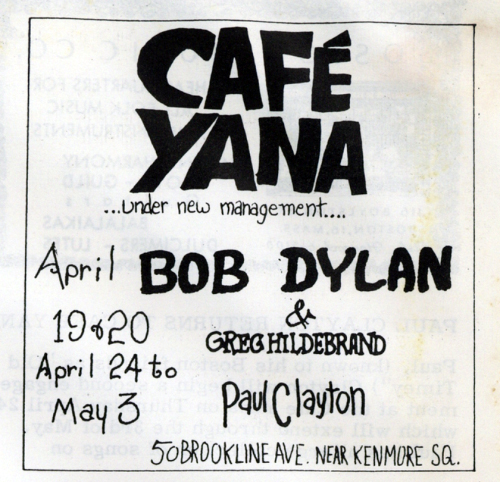

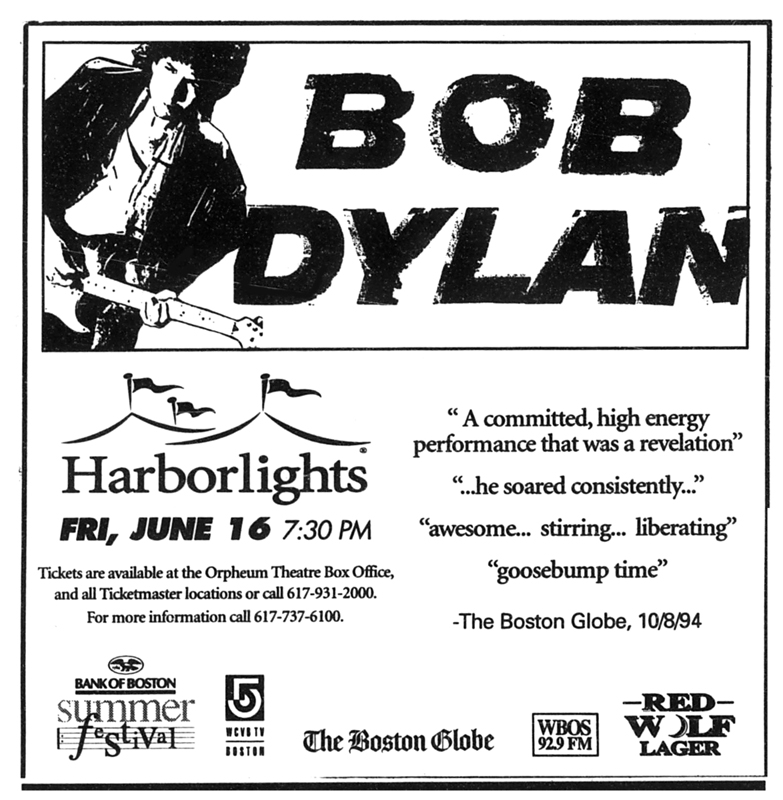

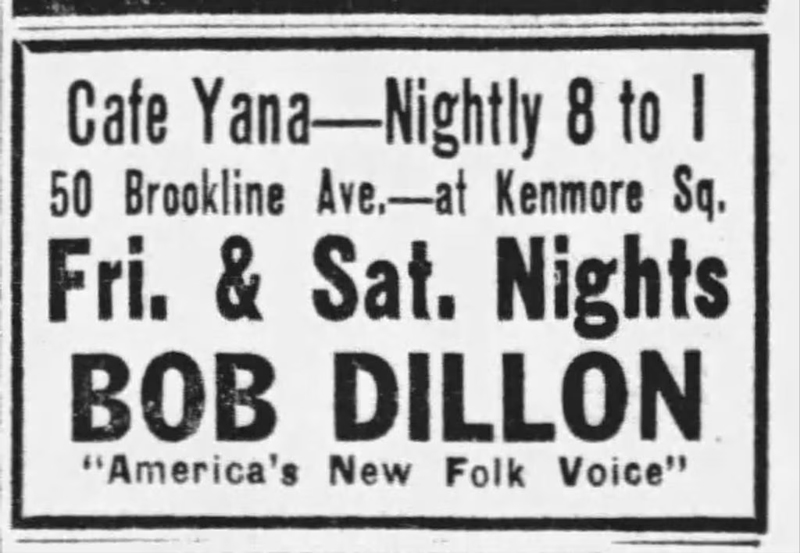

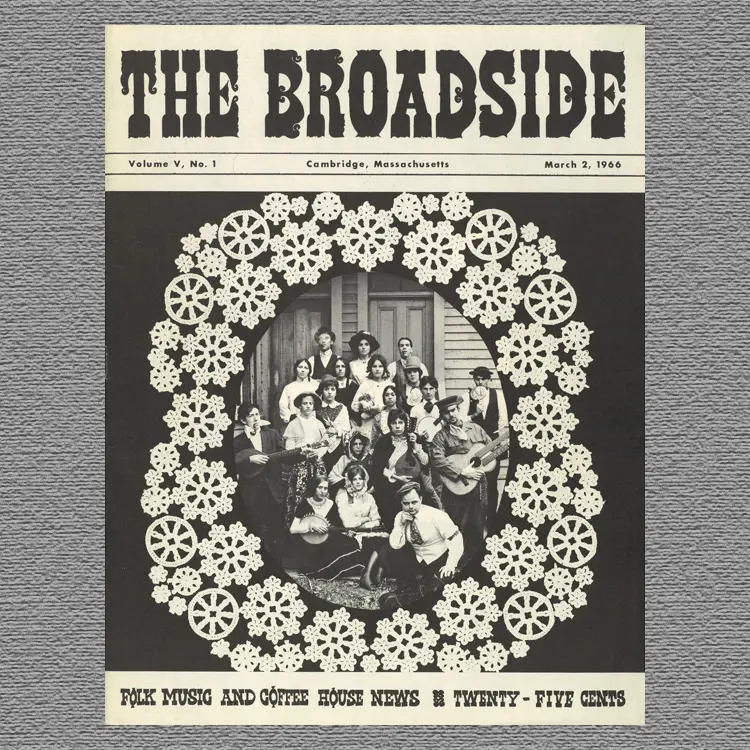

On April 19, 1963, five weeks before Columbia issued his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Dylan made his official Boston debut at Café Yana, a popular coffeehouse that held about 40 people. His name was misspelled “Bob Dillon” on the promo poster, the catch copy read “America’s New Folk Voice” and he appeared at the Yana again the following night. One week before the first show, Cambridge-based biweekly The Broadside published a piece called “Bob Dylan: A Café Yana Surprise,” announcing it with an excitement rarely seen in the famously reserved, understated folk press: “There is no other young performer today with as much magic surrounding his name,” the article said. “As far as we know, this will be Bobby’s first Boston appearance – professionally at least.”

Before Dylan took the stage on the first night, waitress Susan Bluttman asked him to play “Blowin’ in the Wind,” according to a 2023 article by Ryan Walsh in The Boston Globe, which took Dylan aback since the song hadn’t been released. He’d been performing it live for a year before the Yana shows, however (the first time being at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village in April 1962), and a number of folk artists had added it to their set lists. WBC-TV in New York City had taped Dylan performing the song in their studios the month before the Yana shows, but the station didn’t broadcast the tape until May, about a month after the Yana gigs (marking Dylan’s television debut).

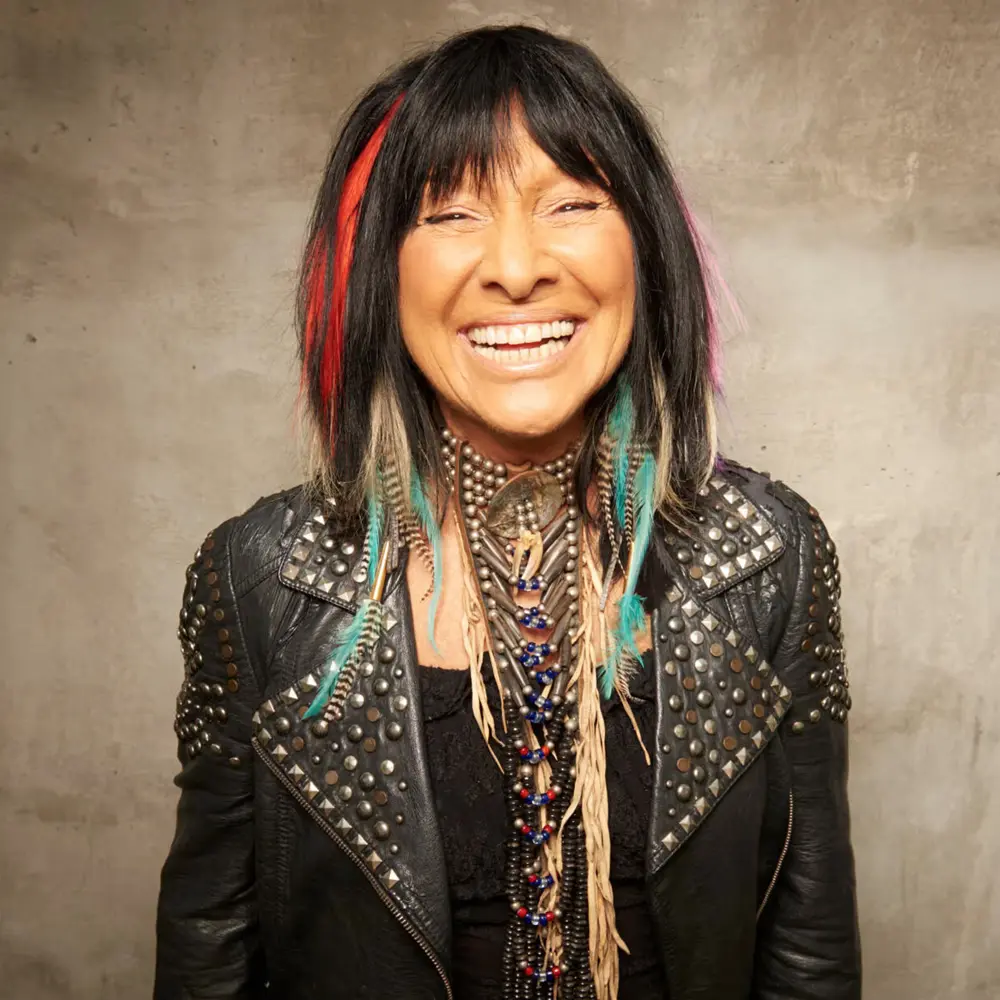

“He looked at me like, ‘Where the fuck did you hear that song?’” Bluttman said, according to Walsh. “I told him that Buffy Sainte-Marie covered it when she performed at Yana a few months prior.” Dylan obliged her request, making that night the first time that he played “Blowin’ In the Wind” for a Boston (and probably a New England) audience. Just five weeks later, it was issued as the opening track The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, which also included the three other songs he played at the Yana shows: “Girl From the North Country,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Masters of War.”

CLUB MOUNT AUBURN 47, NEWPORT ‘63, FOLKLORE, DICK WATERMAN

On April 21, the night after the second Yana show, Dylan made his first official appearance at Club Mount Auburn 47 (renamed Club 47 later in 1963). He’d played there once before, in August 1961, but not with an actual booking; he’d convinced Carolyn Hester to allow him on stage during her set. Dylan played three songs, the first being the traditional “Glory, Glory” as a duet with von Schmidt, followed by two originals that he performed solo, “Talkin’ World War III Blues” and “With God on Our Side.” He did not play “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

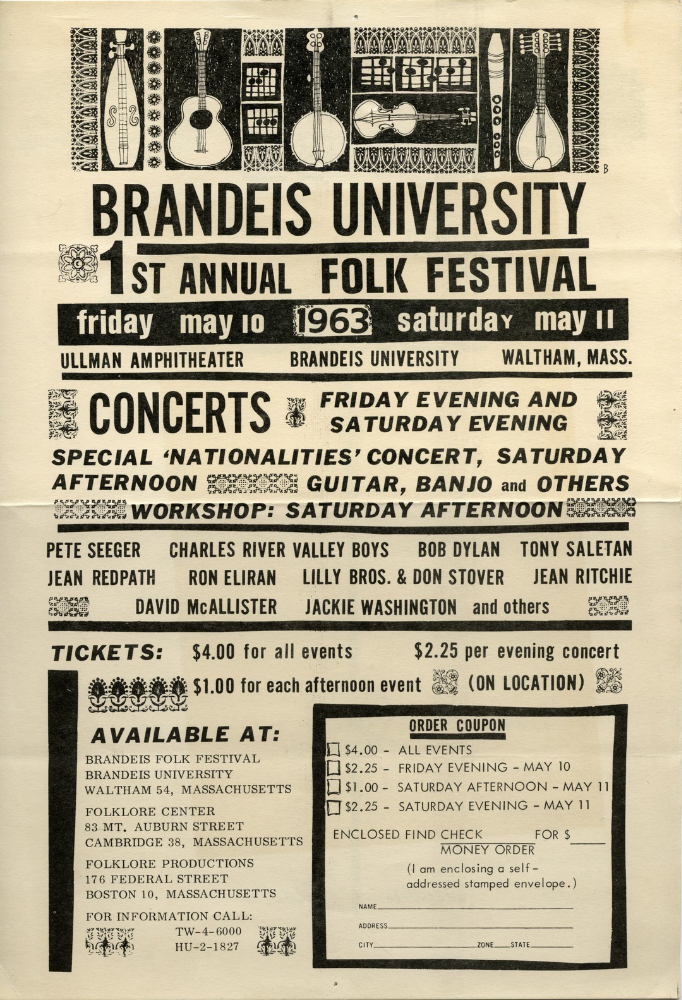

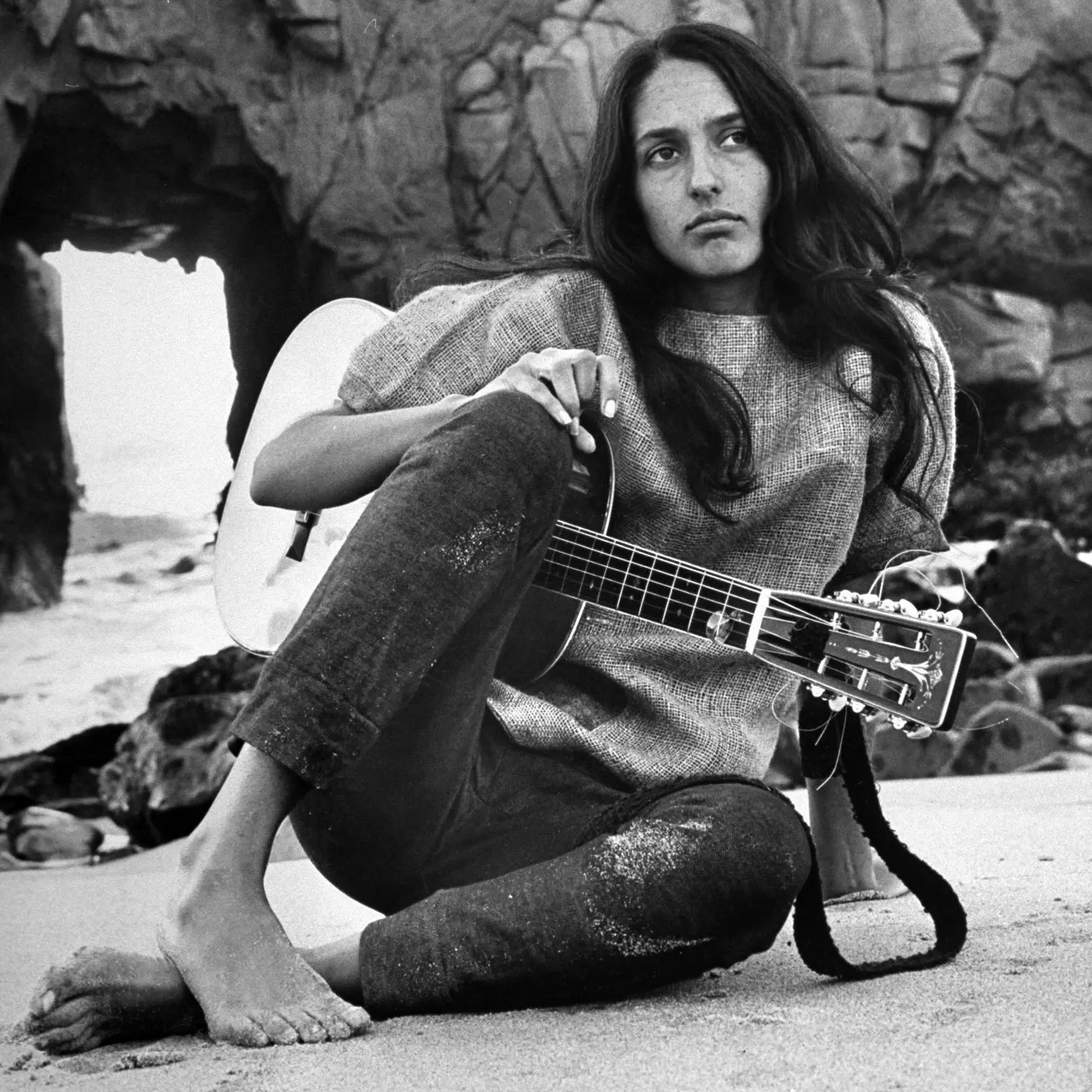

Less than three weeks later, on May 10, Dylan played a seven-song set at the Brandies Folk Festival in Waltham, Massachusetts, and on July 26 he debuted at the Newport Folk Festival, where he “went from zero to hero in the course of a weekend,” said rock photographer Rowland Scherman on NPR’s All Songs Considered in 2009. “It was his emergence from being just a songwriter to being the grand guru, the grand poohbah of all folk music. By the end of the weekend, he was untouchable.” In the afternoon workshop section of the day, Dylan played “North Country Blues” and “With God On Our Side,” the latter as duet with Joan Baez. In the evening, he performed “Talkin’ World War III Blues,” “Who Killed Davey Moore” and “Only A Pawn In Their Game” solo, then “Blowin’ in the Wind” with Baez, Peter Paul and Mary, Pete Seeger and The Freedom Singers as his back-up vocalists.

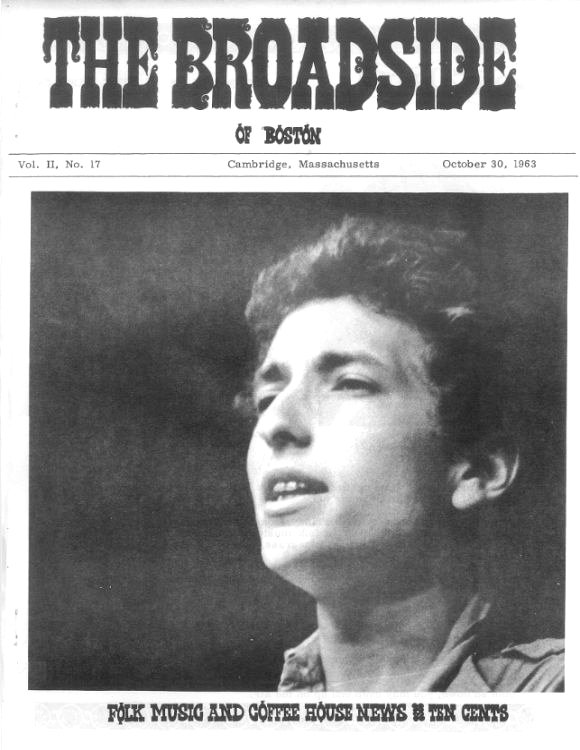

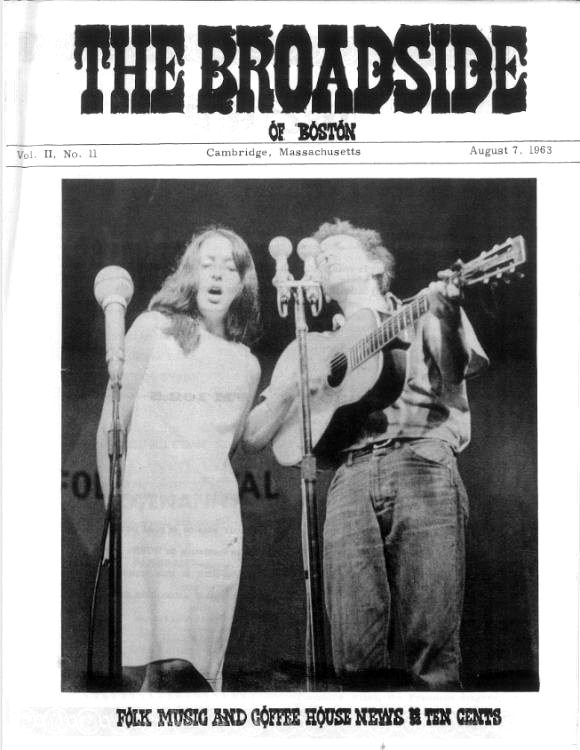

In October 1963, Dylan appeared on the cover of The Broadside after being interviewed by Dick Waterman, a Plymouth, Massachusetts native who was the paper’s features editor at the time and became a major figure on the local and national folk-blues scenes. In November, he performed at Jordan Hall in Boston and he appeared in New England a number of times in 1964, including shows in Boston, Cambridge, Springfield, New Haven and Orono, with Folklore Productions founder Manny Greenhill booking many of the gigs.

NEWPORT ’64, TOM WILSON, NEWPORT ’65, “GOING ELECTRIC”

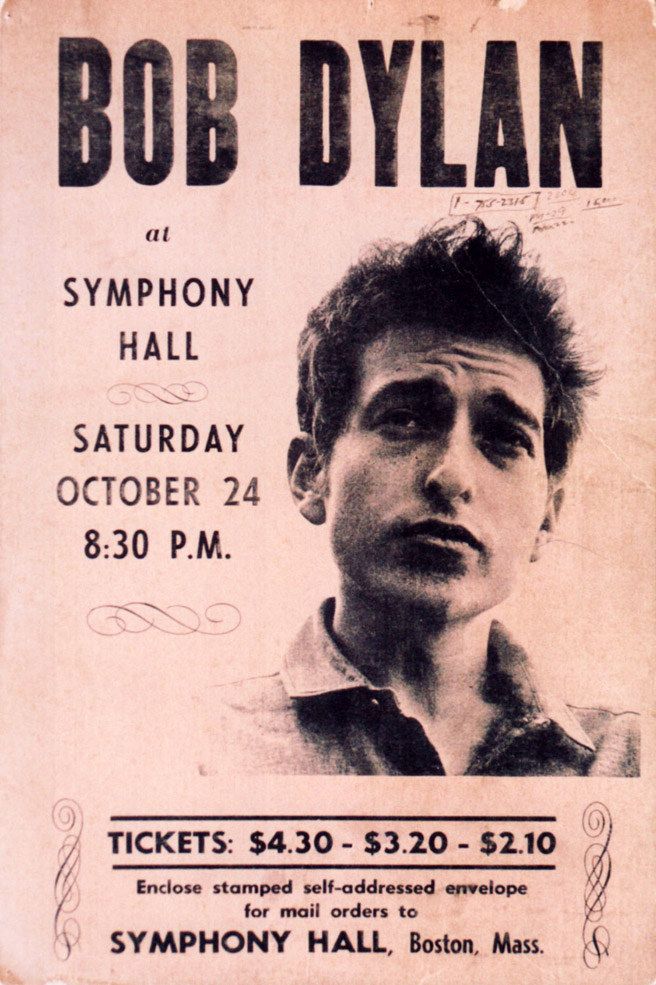

Dylan returned to Newport in July 1964, again playing solo and with Baez. The appearance came five months after the release of his third LP, The Times They Are A-Changin’, which had another direct connection to New England: It was produced by Harvard graduate and former WHRB deejay Tom Wilson, who’d produced four tracks on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and went on to produce Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964) and Bringing It All Back Home (1965). In October 1964, the 23-year-old singer-songwriter debuted at Symphony Hall in Boston for a sold-out show booked and promoted by legendary local impresario Fred Taylor, future co-owner of The Jazz Workshop/Paul’s Mall.

In July 1965, Dylan made his third Newport appearance and did something anyone even remotely familiar with the history of popular music knows about: he “went electric,” which turned out to be as pivotal an event as Elvis Presley’s and The Beatles’ debuts on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956 and 1964 respectively. Expecting to see their beloved young acoustic troubadour performing a solo set, people in the 13.000-strong audience were gobsmacked when he took the stage with a full electric band, some sitting in stupefied silence while others booed and hissed in palpable, rage-laden disgust.

“Some of Dylan’s own friends and mentors reacted as if his performance were a personal attack,” wrote The New York Times’s Tom Piazza in 2002. “The show has been one of the most written-about and debated events in the history of popular music, seen by nearly everyone – pro or con – as a portent of the split between a commercially driven youth culture and the politically committed folk establishment.” Dylan did not appear at Newport again until July 2002, 37 years after his transformation from the critics’ darling of the folk community to the poet laureate of the rock one.

ROLLING THUNDER REVUE, JACK KEROUAC, CIDNY BULLENS

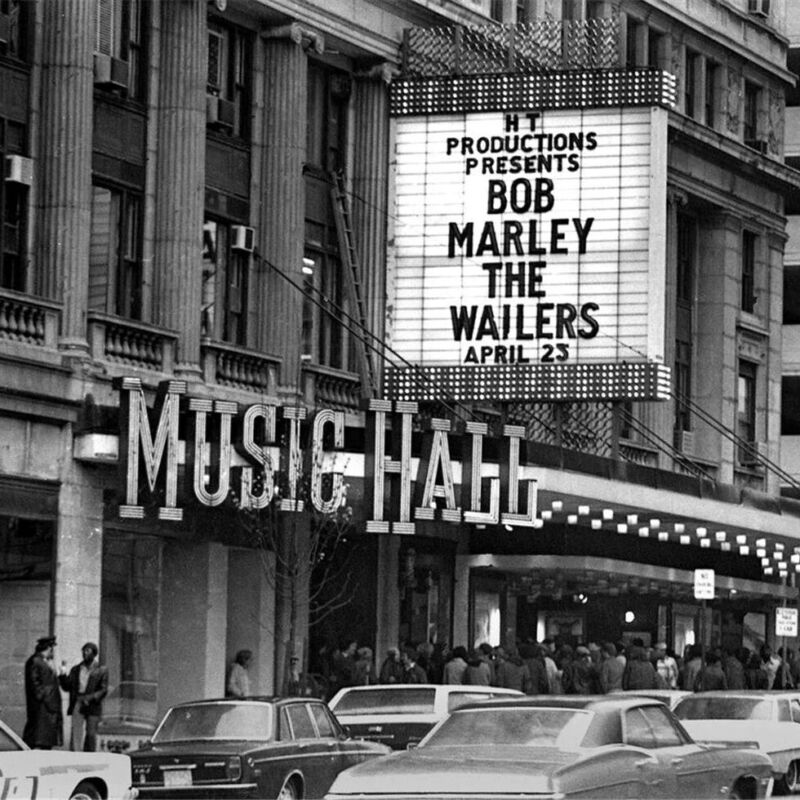

A decade after shocking the world at Newport, Dylan began his 57-date Rolling Thunder Revue tour on October 30, 1975 at the 1,500-seat Memorial Hall in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Over the next month, he played 18 shows across New England, at least one in every state; venues included Music Hall (Boston), the Harvard Square Theatre (Cambridge), the Providence Civic Center, the Palace Theatre (Waterbury, Connecticut), Patrick Gym (Burlington, Vermont), Lundholm Gym (Durham, New Hampshire) and Bangor Auditorium (the last show of the New England leg). While he could have sold out any stadium in the developed world for multiple nights, he chose smaller auditoriums because, as he told Rolling Stone magazine in December 1975, “the atmosphere in small halls is more conducive to what we do.”

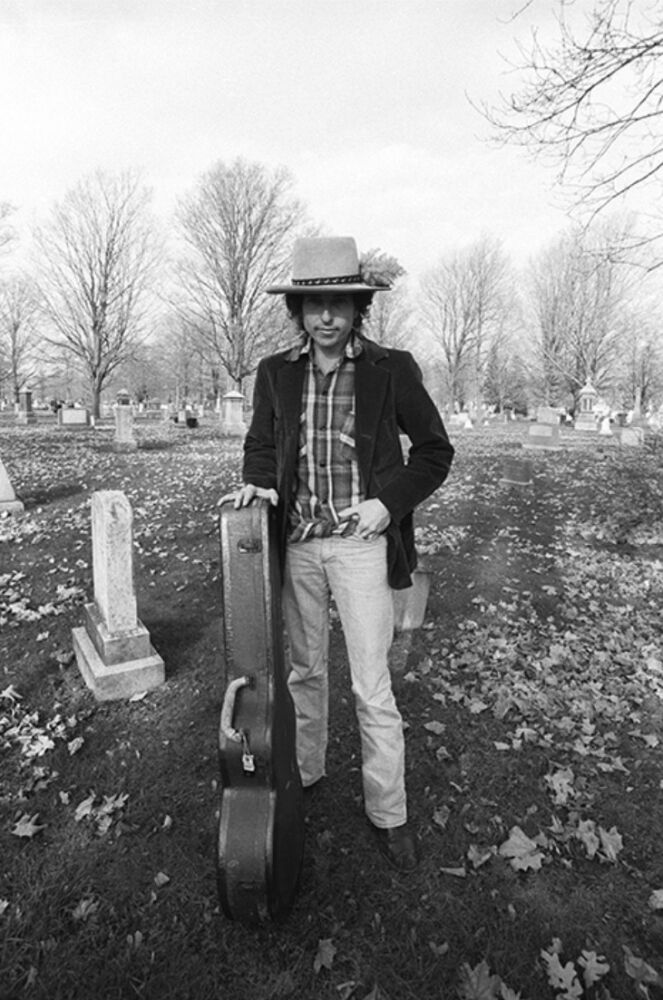

On November 3, the day after appearing at the University of Lowell, Dylan went to the city’s Edson Cemetery to visit the gravesite of writer Jack Kerouac, a Lowell native who “had just as big an impact on me as Elvis Presley,” Dylan said at the time, adding that he booked the Lowell gig specifically for that reason. In December, when Dylan played at Madison Square Garden, singer-songwriter Cidny Bullens, a Newburyport, Massachusetts native, joined the on-stage ensemble.

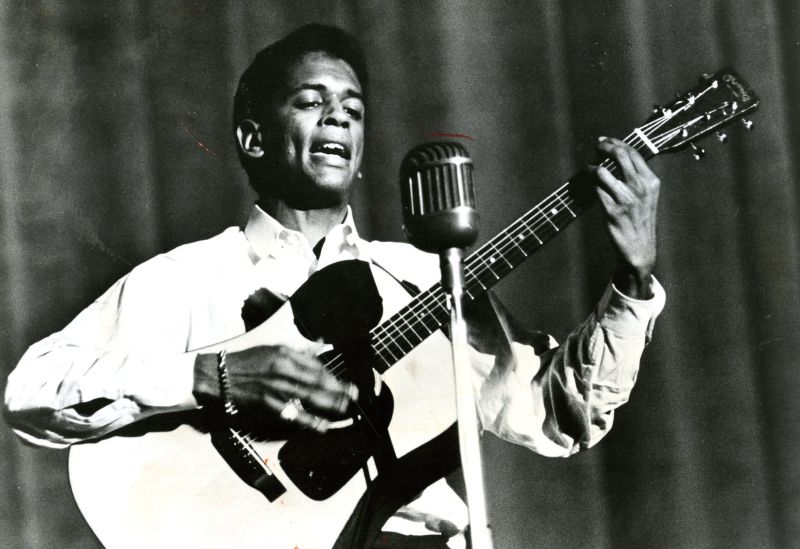

JACKIE WASHINGTON, BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE

Among Dylan’s many other connections to New England is singer-songwriter Jackie Washington, who was raised in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood and was a mainstay at the area’s coffeehouses and clubs in the ‘60s. Washington claimed that Dylan’s “Masters of War” was a blatant rip-off of his own arrangement of the folk standard “Nottamun Town”; the allegation was widely publicized in folk circles and Washington explained the details in Baby, Let Me Follow You Down: The Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years (University of Massachusetts Press, 1994). Though he never sued Dylan, Washington swung back passive-aggressively in his 1967 song “Long Black Cadillac,” an obvious parody of Dylan’s 1965 classic “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Another noteworthy connection to the region is that in early 1964, after hearing Wakefield, Massachusetts-raised Buffy Sainte-Marie perform at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village, Dylan was instrumental in landing her a spot at the Gaslight Café, which led to Vanguard signing the 23-year-old singer-songwriter to her first record deal about a month later. “He heard me play, he liked it and he said, ‘Go see Sam [Hood, owner of The Gaslight Café]’ and within a week or two [New York Times music critic] Robert Shelton came to see me play and wrote a glowing review,” Sainte-Marie said in 2006.

OTHER NEW ENGLAND CONNECTIONS

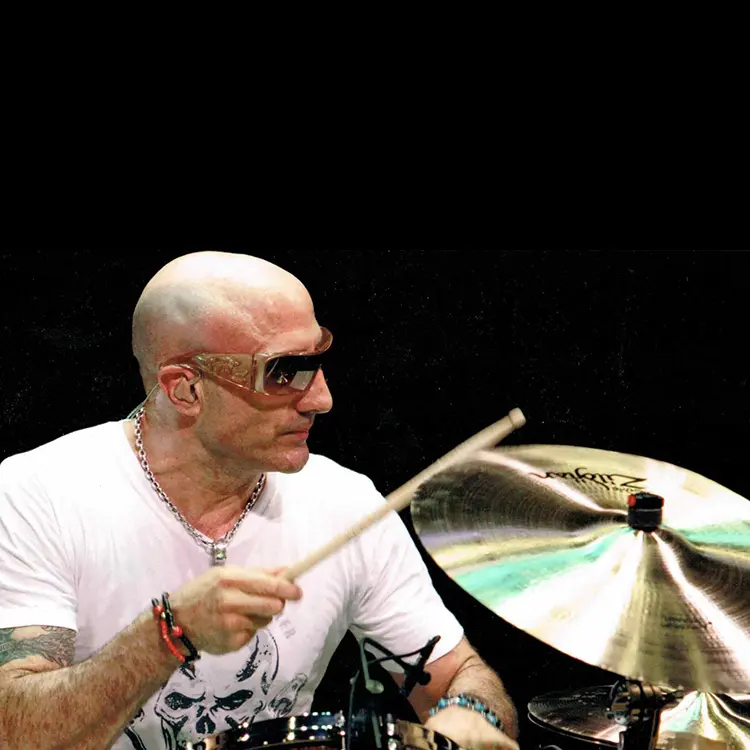

Like innumerable other New England-based folk and rock artists who’ve cited Dylan as a towering early influence, singer-songwriter Jonathan Edwards has said that Dylan inspired him to go electric; Edwards’ song “Sunshine,” which hit #4 in the Billboard Hot 100 in 1972, is a quintessential example of “folk rock,” the genre Dylan is widely credited with inventing. Among the New England-rooted musicians who’ve recorded and/or toured with Dylan are Roomful of Blues co-founder Duke Robillard, guitarist Stuart Kimball of Face to Face, guitarist Duke Levine and drummer Kenny Aronoff.

In late 1984, when bluegrass great and Everett, Massachusetts native Joe Val was having treatment for lymphoma, Dylan visited him in the hospital, as did Baez. In 1985, when Dylan recorded his Empire Burlesque LP, Massachusetts native Arthur Baker did the mixing. Joe Spaulding, the CEO of Boch Center in Boston, was in the audience at Dylan’s seminal Newport appearance in 1965 and has said that it played a significant role in his decision to pursue a career in the music business.

More recently, Dylan made two subtle nods to New England on the dedication page of his book The Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster, 2022). The first is his inclusion of Eddie Gorodetsky, a native Rhode Islander and Emerson College graduate who was WBCN’s head writer in the late ‘70s and produced the Dylan-hosted Theme Time Radio Hour series on SiriusXM from 2006 to 2009. The second is a reference to a company founded in Quincy, Massachusetts in 1950 that’s become nearly as famous across the globe as Dylan himself: “To all the crew at Dunkin’ Donuts,” he wrote.

(by D.S. Monahan)