Symphony Sid

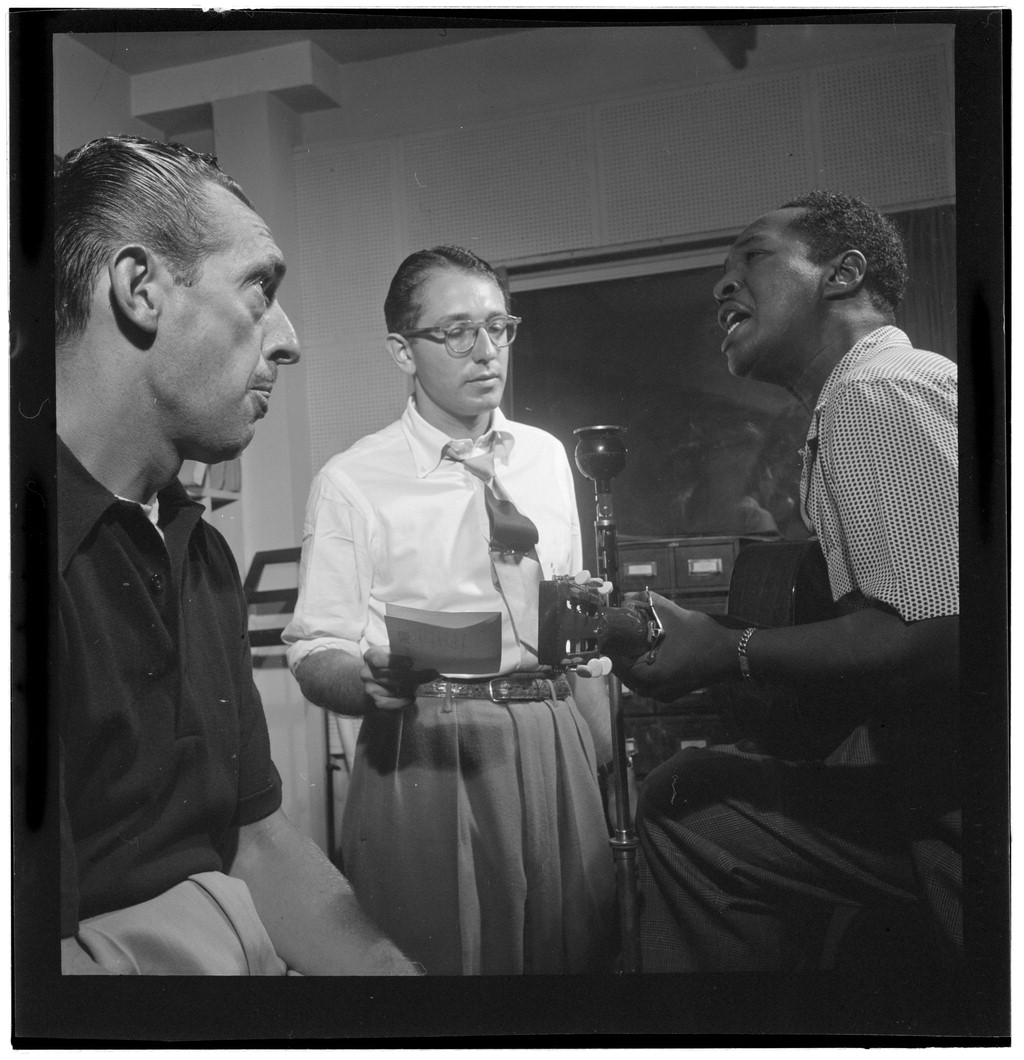

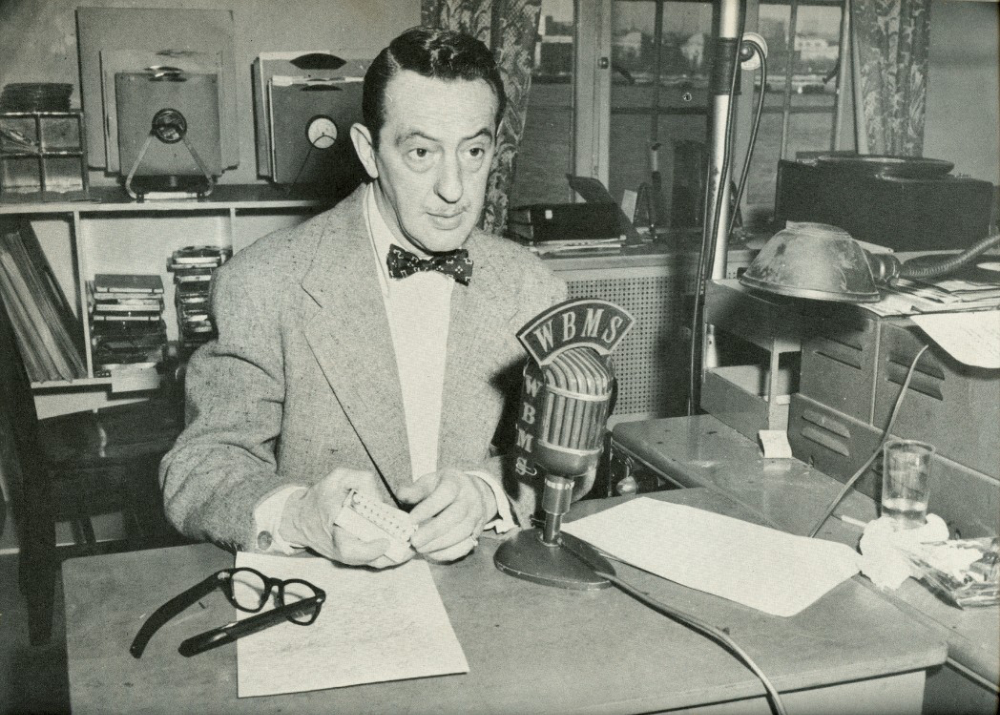

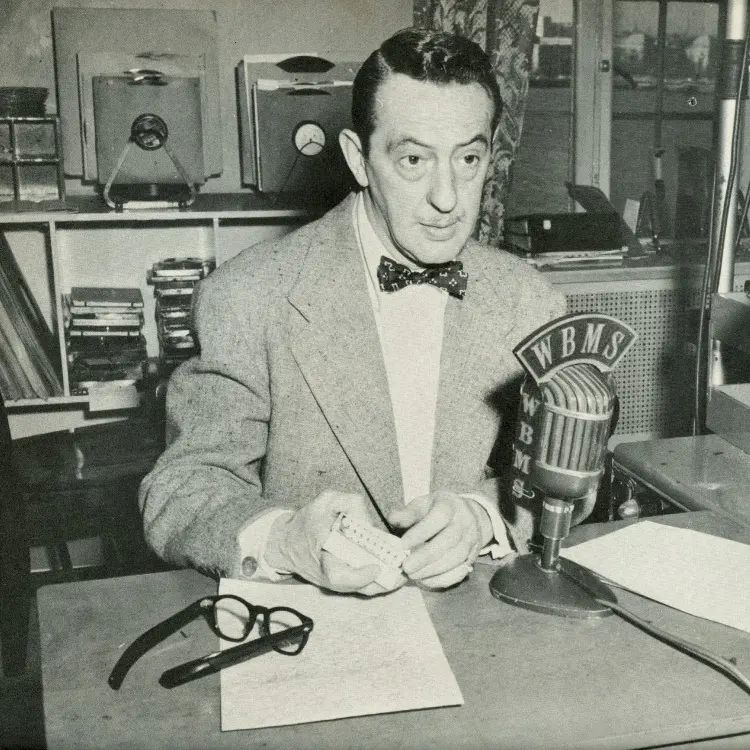

Symphony Sid at WBMS 1955

Disc jockey Sid Torin, best known as “Symphony Sid,” was among the most famous figures in jazz radio for 35 years, from the late 1930s through the early 1970s. He spent all but the middle five years of his career in New York city, but was an enormously powerful presence on Boston’s airwaves from 1952 to ‘57.

Born Sidney Tarnapol in New York City in 1909, he changed his name to Torin after turning 18 and worked at Symphony Record Shop in the late 1930s. He adopted the on-air handle Symphony Sid after landing his first radio gig, a 15-minute afternoon jazz show on WBNX in the Bronx called After School Swing Session that became wildly popular among the younger crowd. He only spun records by Black artists, which allowed him to establish a major following in the Black community.

WHOM, WMCA, WJZ, “Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid”

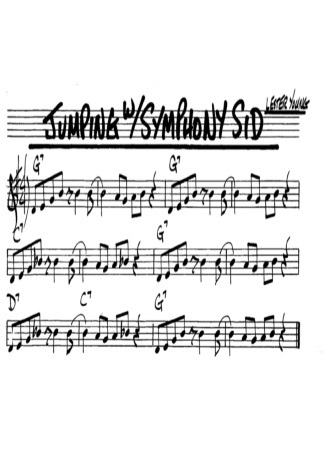

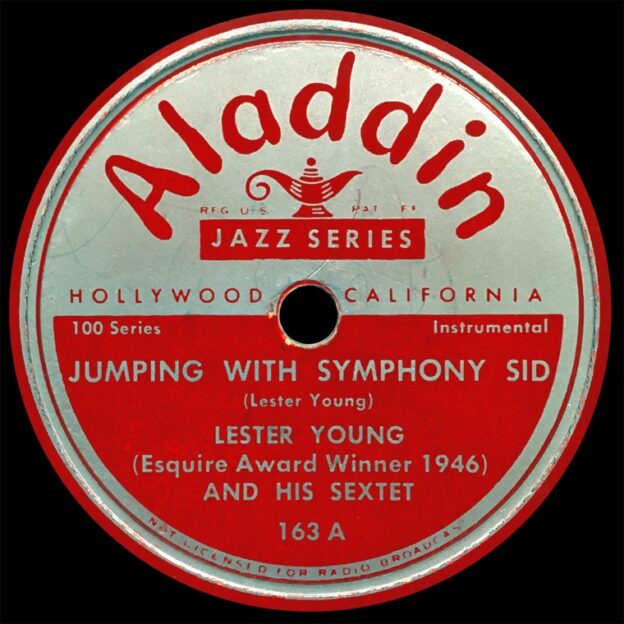

By 1941, he was on WHOM dong an overnight show, After Hours Swing Session and his popularity soared. In 1946, Lester Young wrote and recorded the tune that became his theme song, “Jumpin’ with Symphony Sid,” and as the 1940s progressed, Torin turned his focus to the new generation of bebop artists, championing the music of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. He often hosted remote broadcasts from The Royal Roost, Birdland and other famous clubs, eventually landing at ABC affiliate WJZ, which aired in 30 states and allowed him to introduce bebop to millions.

Things began to unravel for Torin in New York City when he was arrested for possession of marijuana, although his sentence was suspended. To complicate matters, he was tossed off the air at WJZ because one of his guests let loose with some profanity over an open microphone. Though he couldn’t get back on the radio immediately, he continued to support the artists and music he loved by working as an emcee at clubs and concerts. And that’s what first brought him to Boston.

Move to Boston, WBMS, Interlude in Jazz, Brother Sid’s Gospel Hour

In the early ‘50s, Torin toured with Jazz Unlimited, a group that featured some of the top stars of modern jazz, including vibist Milt Jackson and trombonist J.J. Johnson. When the show rolled into Boston for a week at The Hi-Hat in May 1952, he mentioned to WBMS General Manager Norman Furman that he wanted to get back on the air and Furman offered him a job. Torin accepted the position without a moment’s hesitation. Furman’s focus at WBMS was on the Black audience – which wasn’t served at all in the city at the time – and he thought Torin, who loved Black music, understood the audience and had a certain star quality of his own after his years in the Big Apple – would be a major asset to the station.

Torin had an afternoon program called Interlude in Jazz, but he played more than just that; he broke R&B records by The Ravens, The Orioles and others on the show. And his interests didn’t stop with jazz and R&B; he hosted another program in the late afternoon, Brother Sid’s Gospel Hour. Picture it: at a time when Boston radio was mostly about Eddie Fisher and Patti Page, Symphony Sid rocked the town with Max Roach, The Five Keys and Clara Ward. Now it was Boston that was jumpin’ with Symphony Sid!

WCOP, The Hi-Hat, “The Jazz Corner Of Boston,” Other activities

WBMS was a daytime-only station, meaning it went off the air at sundown, but Torin wanted a nighttime audience so he arranged with Furman to work nights at WCOP and began doing remote broadcasts from The Hi-Hat. The club built a glass booth at the side of the stage in which Torin spun records from 10pm to midnight. After those two-hours, he’d step out of the booth to announce the headliner and broadcast a 30-minute live set. It was Torin who first called The Hi-Hat’s location at Massachusetts and Columbus Avenues “the Jazz Corner of Boston,” a riff on his calling New York’s Birdland at Broadway and 52nd “the Jazz Corner of the World” a few years earlier.

Sometimes Torin lost track of where he was, to humorous effect. Boston newspaperman Bill Buchanan never tired of telling the story about the night he was listening to his show on his car radio and heard him announce, “It’s the music of Slim Gaillard coming to you from The Hi-Hat in Boston”…and there was a pause… “and you’re listening to either WBMS or WCOP.” Torin had various other enterprises besides radio, one of which was selling records, specifically his “Selections of the Month.” He’d pick three R&B singles that he thought were potential hits, package them in an album and sell them in the department stores.

WMEX, Criticism, Return to New York City

By November 1955, Torin had moved from WCOP to WMEX, still airing from The Hi-Hat. The remote broadcasts ended abruptly in December, though, when a fire ravaged the club and it stayed closed for about a year. Then it reopened, the live broadcasts did not resume.

As popular as he was in general, Torin did have his share of critics. Some found his hipster routine tiresome and not all of his jazz listeners welcomed his embrace of R&B. But he knew what he was doing and was quite consciously working to appeal to a young, multi-racial audience, as he viewed the R&B listener of today as the jazz listener of tomorrow. That might have been too optimistic, but the fact remains that he played lots of great records when other deejays didn’t, and lots of listeners dug them.

Torin remained on the air in Boston until August 1957, by which time Furman had moved to WEVD in New York City, with plans to focus the station on Black music. Again he offered Torin a job, which Torin accepted, saying farewell to Boston as emcee of the North Shore Jazz Festival in Lynn that month.

Time was running out for Torin and Furman in Boston anyway. WMEX had been sold to Max Richmond, who instituted a rock-centric top-40 format and Torin would simply never play any of those records. WBMS was about to be sold to Bartell Broadcasting and Furman would likely be let go when that deal completed. Bartell changed the call letters to WILD, but they retreated from the focus on Black music. It took a few years to get it back, but Furman and Torin left something in the station’s genes that came to life in the 1960s.

Later years, Retirement, WBUS, Death

Torin remained on the radio in New York for another 15 years. He embraced Latin music in the 1960s, playing Tito Puente and Eddie Palmieri with the same enthusiasm he brought to Charlie Parker in earlier days. In 1972, after 35 years in on the air, he retired to the Florida Keys but he couldn’t stay away from the microphone; in 1974, he hosted a weekend jazz show on WBUS in Miami. “Symphony Sid” Torin died in Miami at age 74 on September 14, 1984.

(by Richard Vacca)

Richard Vacca is the author of The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937- 1962 (Troy Street Publishing, 2012) and coauthor with Fred Taylor of What, and Give Up Showbiz?: Six Decades in the Music Business (Backbeat, 2020).