Storyville

Storyville

New England’s cities have been home to some good jazz clubs over the years, and even a few great ones. Perhaps the greatest of them all was Storyville, the Boston club operated by George Wein in the 1950s. Wein presented the best in jazz regardless of style—everything from piano soloists to big bands, and from bebop to Dixieland.

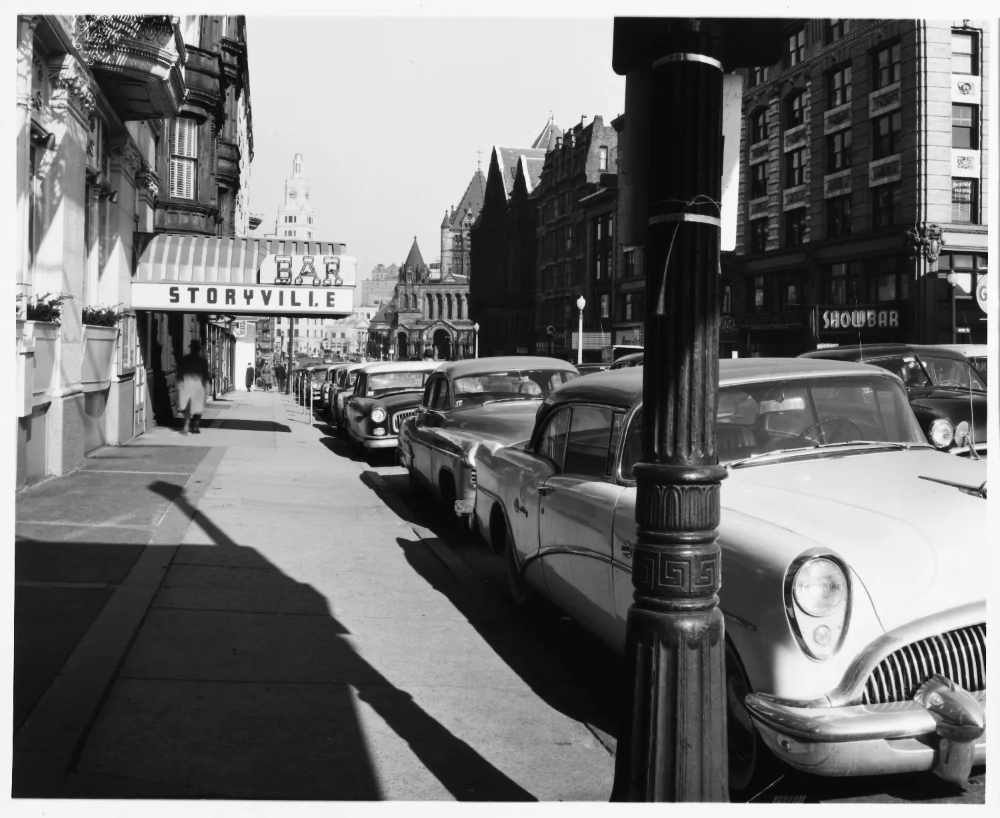

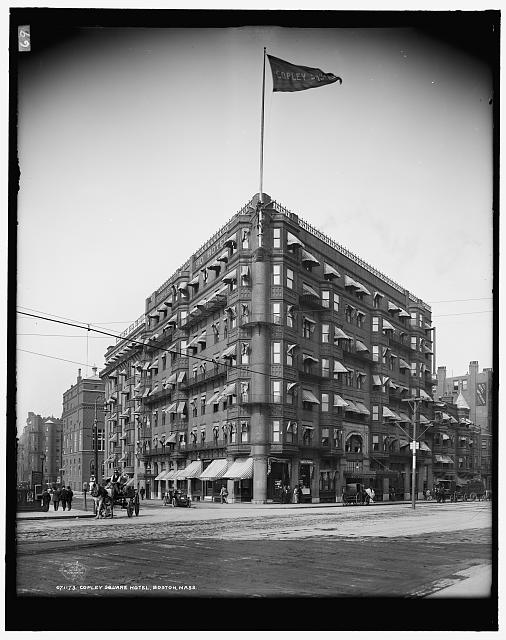

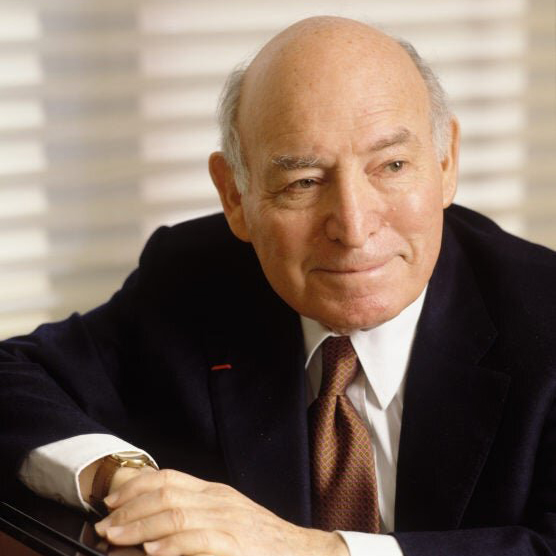

George, energetic and ambitious, was 25 in October 1950 when he opened Storyville in the Copley Square Hotel. He named it after the New Orleans red light district where many believe jazz was born. He closed the club after only six weeks, following a dispute with the landlord, but he reopened in the Buckminster Hotel in Kenmore Square in February 1951. When new owners assumed control of the Copley Square Hotel, he moved back in September 1953. Storyville stayed there until Wein closed its doors in May 1960.

That’s the thumbnail sketch. But what made Storyville such a great club? It was a combination of things: George’s energy and ideas, the vibe of the room, and the jazz artists who played there.

The Proprietor

If there was one person synonymous with jazz in Boston in the 1950s, it was George Wein. He ran Storyville, as well as a second club, Mahogany Hall. He wrote a newspaper column, spun records as a deejay, and taught jazz history at Boston University. He managed artists. For three years he owned and ran Storyville Records. He produced concerts. Finally, he was an accomplished jazz pianist—he formed the Newport All-Stars and toured with the group every summer.

His crowning achievements were founding the Newport Jazz Festival in 1954 and the Newport Folk Festival in 1959. His life was a constant quest to bring the music he loved to new audiences wherever he could find them.

George brought one more thing to Storyville: his musician’s sensibilities. He knew what the performing artist cared about, and he created a club where musicians wanted to play and fans wanted to listen. He treated his artists, his patrons, and the music with respect.

A Listening Room with High Standards

Jazz clubs still had a poor reputation in 1950, so he created a club to overcome it. It started with the location, in a Back Bay hotel. That sent the message that Storyville was anything but a dive bar. It was only a 20-minute walk to Izzy Ort’s on Washington Street, but the look and feel of Storyville was a world away from that raunchy downtown joint.

Inside, the lighting was subdued and the sound system was good. There was art on the walls. People still got dressed up to go out in the 1950s, and men wore jackets, ties were optional. No one would think of wearing jeans and tees to Storyville.

It was obvious that you didn’t go to Storyville to socialize. You went to listen. Of course, it was a nightclub, so there was always some noise, but as the critic Nat Hentoff wrote in 1953, “Compared to the other clubs in town, listening to a jazz musician at Storyville is like sitting at home with a pair of earphones.”

There is a footnote. The Storyville crowd was largely white. This was Boston in the 1950s, and although Wein’s doors were open to all, there were black Bostonians who felt uncomfortable in a Back Bay hotel. Some of those establishments—not the Copley Square—were still not admitting blacks as paying customers in that decade.

The Top Names in Jazz

Almost every significant jazz artist of the 1950s, as well as a handful of the decade’s top comics and folk singers, played at Storyville. There isn’t room to mention everyone. There isn’t even room to mention all of the “important” ones. Here is just a baker’s dozen: Louis Armstrong, Art Blakey, Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Ahmad Jamal, Lambert Hendricks & Ross, Thelonious Monk, Anita O’Day, Max Roach & Clifford Brown, Art Tatum, Mary Lou Williams, Lester Young.

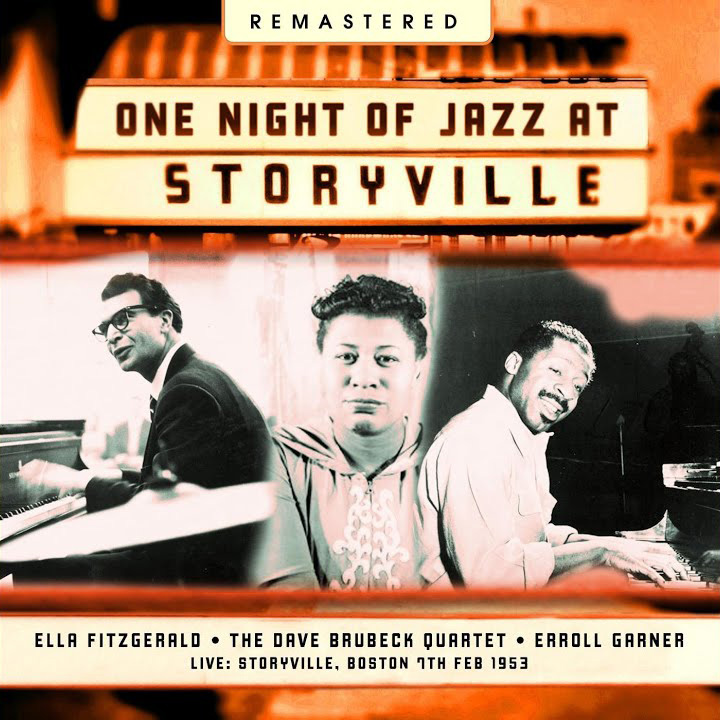

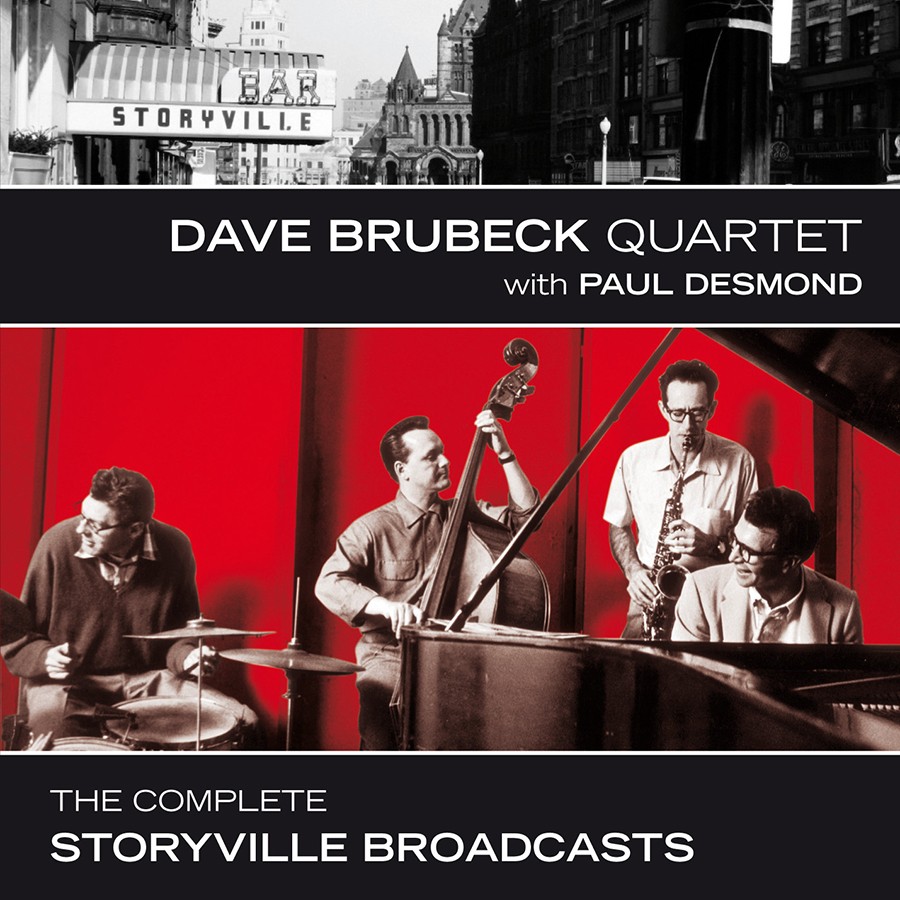

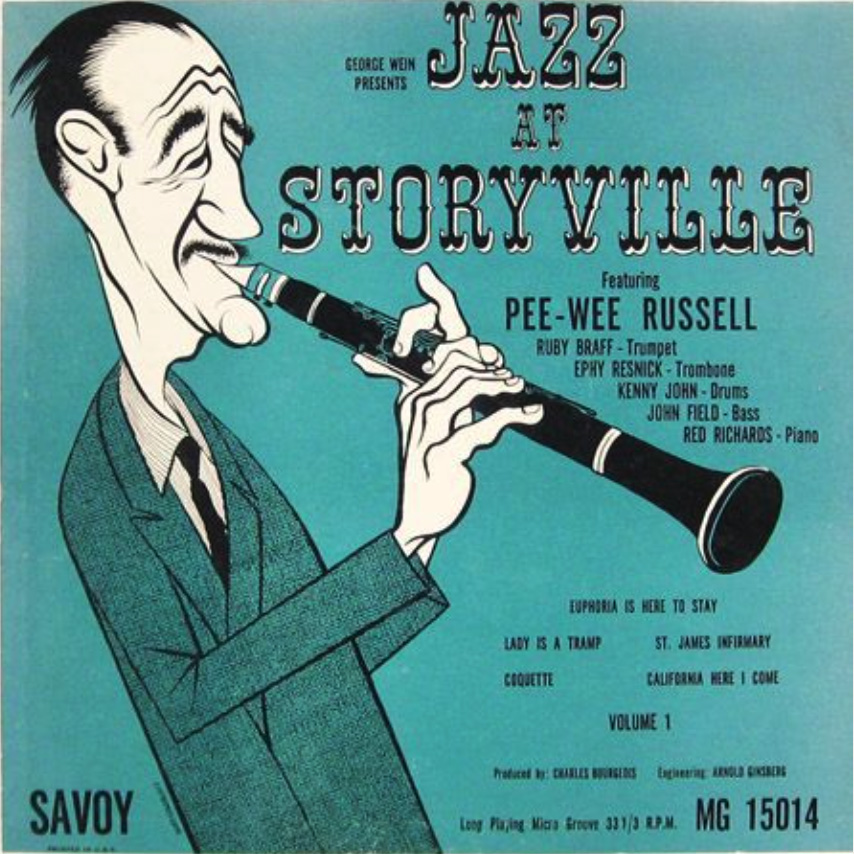

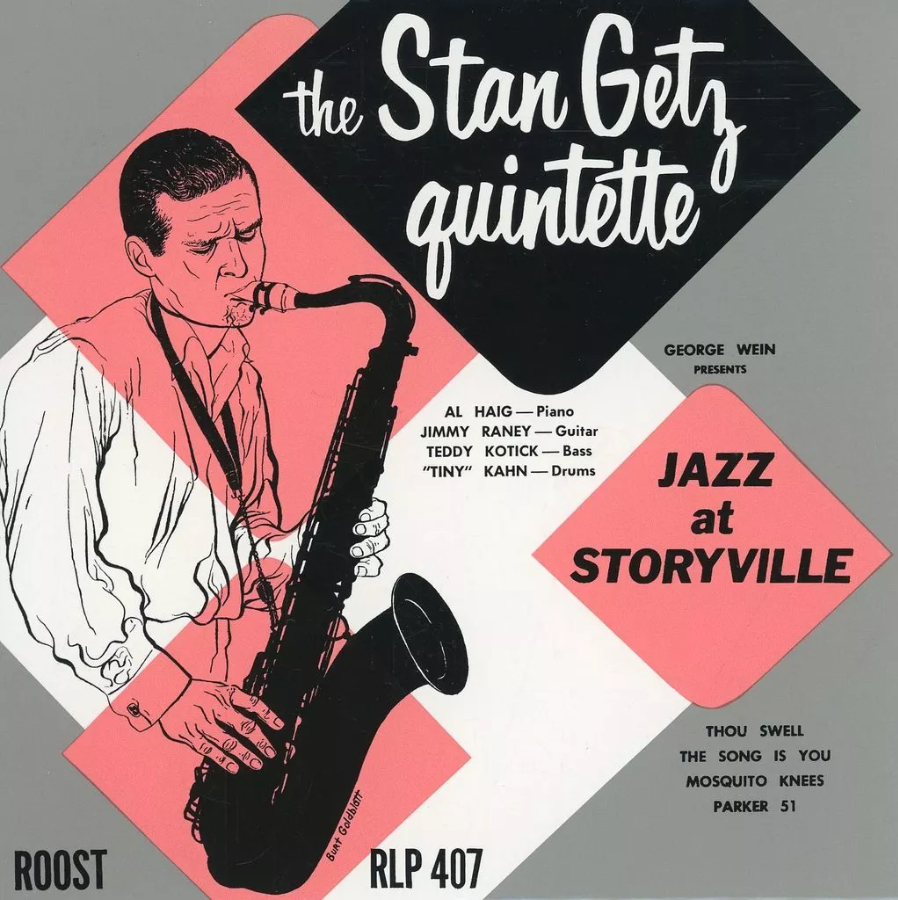

Nine more who recorded an album at Storyville: Sidney Bechet, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, Billie Holiday, Teddi King, Gerry Mulligan, Marian McPartland, Pee Wee Russell, Billy Taylor.

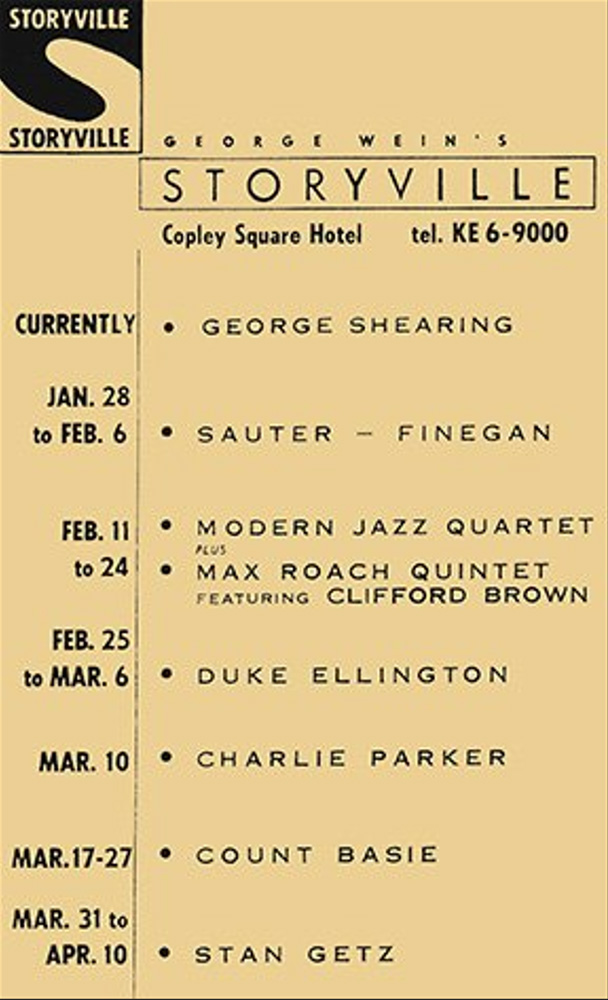

In 1955, a particularly strong year for Storyville, the schedule included Duke Ellington, Max Roach and Clifford Brown, Erroll Garner, Gerry Mulligan, and Sarah Vaughan. Charlie Parker was scheduled to play on March 12, 1955—the night he died. And these weren’t one-nighters. Bands were booked for the week.

If you wanted to hear a name band in Boston, clearly Storyville was the place to be.

A Decade Ends, a Club Closes

Storyville was an artistic success, but it was not a financial one. Despite the abundant talent, the club’s existence was always precarious.

It’s a fact of nightclub life that only some artists can sell out the house, and they subsidize the ones who can’t. Wein had his A-list (Ellington, Garner, Vaughan, Mulligan, George Shearing), and he counted on the support of their fans. But Storyville was hurt when those top attractions outgrew nightclubs and went into the concert halls. Old standbys Garner, Vaughan, Mulligan, and Shearing skipped Storyville in 1960. Business was so bad that the whole operation shut down for five weeks in the spring. Dinah Washington closed out the troubled season in May.

Like most clubs then, Storyville closed for the summer. When it reopened in September 1960, it was under new ownership and in a new location in the Theatre District. That iteration, without Wein’s leadership, closed in December 1961.

Storyville was gone, but it made its mark. Said Wein in 1966:

The thing about Storyville, is that it was one of the very few jazz clubs in the country to give the musicians a fair shake. Before Storyville, there were mostly joints. We tried to do right by the musicians as well as the music—little things, like having the piano in tune and having good acoustics. We set some decent standards in what was then a pretty crummy business, and we also booked a lot of good talent, which nearly ruined me.

Storyville was the right place at the right time, but times change and tastes change. It was a new decade, and soon new clubs would open to fill the void left by Storyville’s closing.

Richard Vacca is the author of The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937–1962 (Troy Street Publishing, 2012). You can reach him at [email protected].