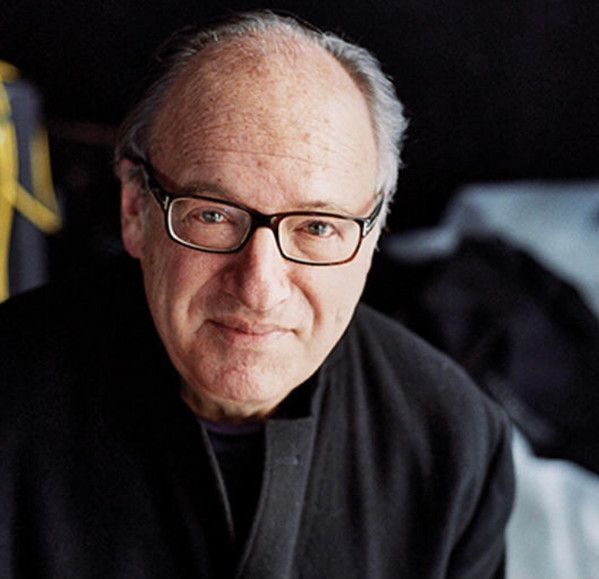

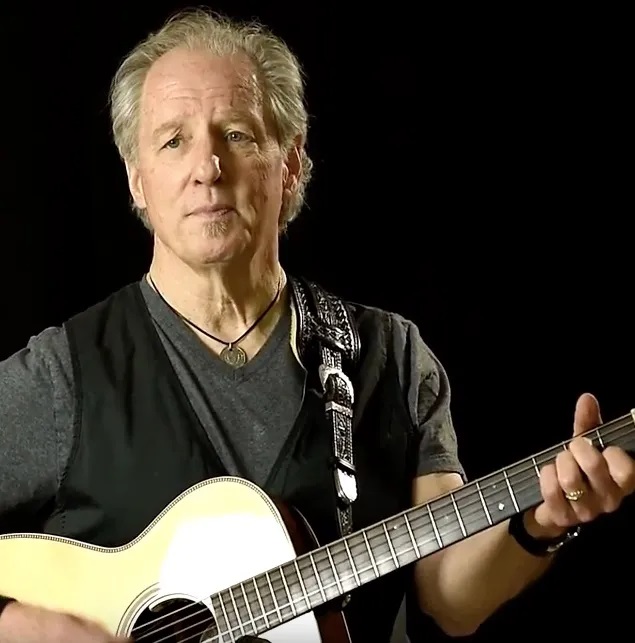

Steve Morse

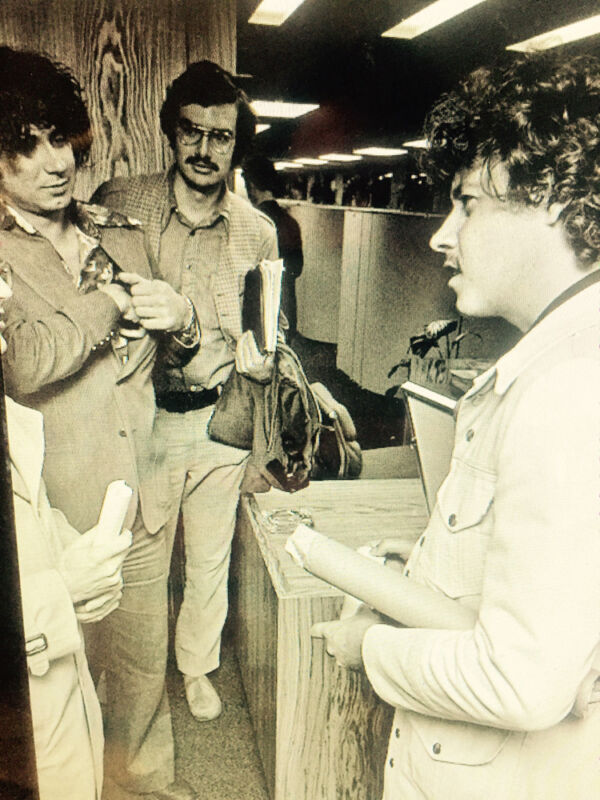

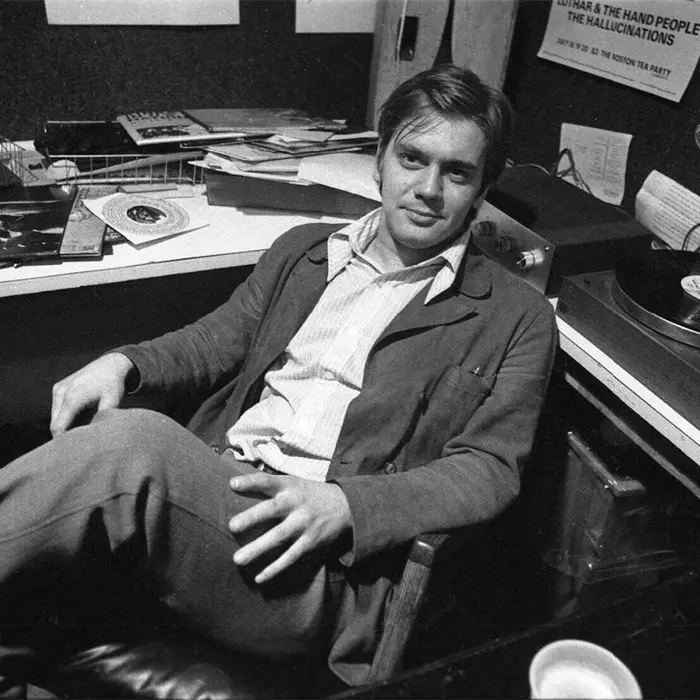

It’s 1972 and Barry Glovsky, the founder, editor and driving force behind the record-review magazine PopTop is working from his Boston office. Barry was a natural-born entrepreneur with a deep love for rock ’n’ roll and PopTop was his avenue into the record business. Available for free to music fans, any given issue could sport reviews of 30 to 50 albums. The salesman in Barry could get the magazine into the stores, but he needed writers to fill the pages.

As he tells it, “Steve Morse just walked into my office one day. He told me that he liked the magazine, would like to write for it and we fell into a long conversation about the world of music – not just rock ’n’ roll – and I quickly realized that Steve really knew his stuff. One thing that surprised me was his passion for country music. I’d never listened to it. He insisted that I check out Hank Williams, Waylon Jennings and others. After we had been working together for a while, he started taking me to clubs to get a better feel for the scene.”

A FULLY EVOLVED CRITIC, AN EDUCATED MUSICAL EAR

Barry and Steve became good friends as well as musical co-conspirators, and Barry describes him as “one of the nicest guys you’ll ever meet” who from day one was a fully evolved music critic. The arc of Steve’s career would prove that statement to be absolutely correct.

I met Steve around the same time. I had a local country-rock outfit called Wheatstraw and Steve was a frequent presence at our shows, usually stationing himself near the back of the room. His presence was notable for a few things. Though he sought to “blend in,” he towered a full head and shoulders above anyone else in the room; not much “blending” going on. It was also clear that he was taking it all in, really listening.

His 11 years of classical-piano training gave him an educated musical ear. His post-college years as a high school social studies teacher sharpened his powers of observation during the period of intense cultural change that was playing out in our national affairs and the music that occupied such a central role in the lives of us emerging Baby Boomers. Steve and I bonded over our mutual love of country music. He was generous in pointing attention to my music and we were good friends for almost 50 years. (Around 1975, Steve brought Barry to a Wheatstraw show, which led to Barry being executive producer of my first two albums and my manager for the next five years).

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, FIRST LIVE SHOWS

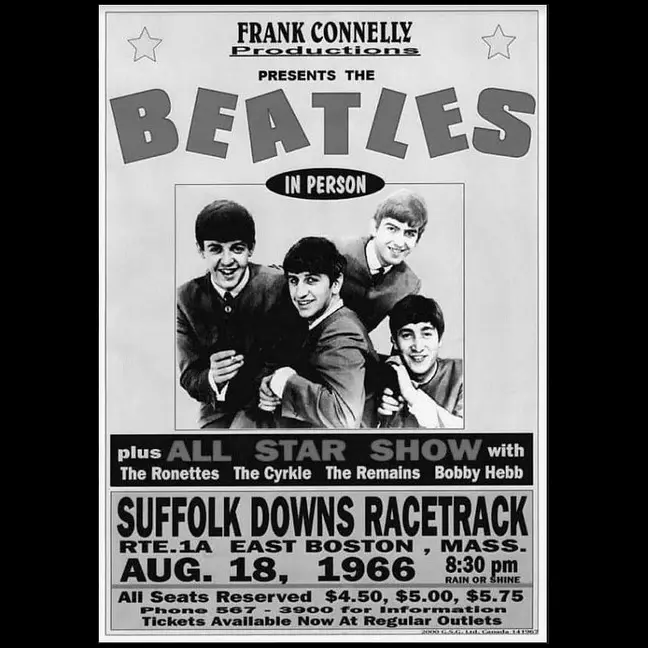

Steve spent his elementary school years in the Boston suburb of Weymouth. Among other glories, Weymouth was home to an important Naval Air Station, manned by Navy personnel from around the country. So country music was in the air, in the local bars and on restaurant jukeboxes. By the 1960s, his family had moved north to Wellesley, providing Steve with a front row seat for the music explosion that was about to hit the city. Steve was 16 when The Beatles invaded in 1964, and like for millions of kids, his life found a new passion.

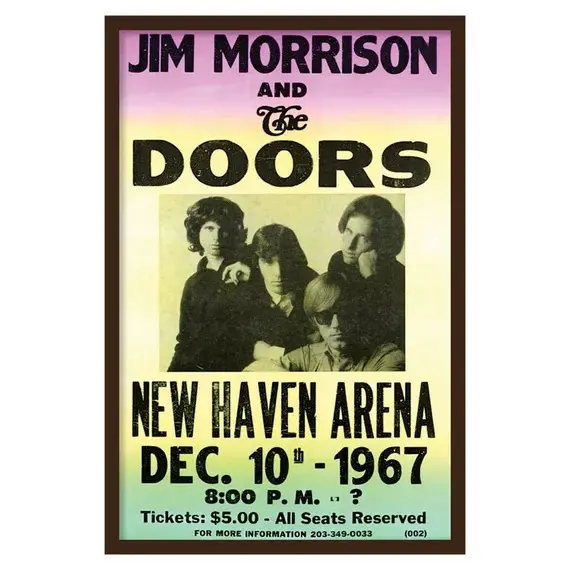

By the time Steve graduated from high school, he was a seasoned concertgoer. Fittingly, his first live show was a Rolling Stones concert at Manning Bowl in Lynn in 1966 (which he described as “complete mayhem”). While at Brown University, he caught shows on campus by artists like The Doors, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. Boston rock music lovers who were in the know were aware that many emerging acts, especially those coming over from England, made their Boston debut at a club called The Boston Tea Party. It provided an intimate space in which to see acts that would go on to be rock ’n’ roll giants. Steve caught bands there like Ten Years After, Fleetwood Mac, the Byrds, the Grateful Dead and others. He spent the summer of 1969 in England and saw shows by the Stones and Led Zeppelin.

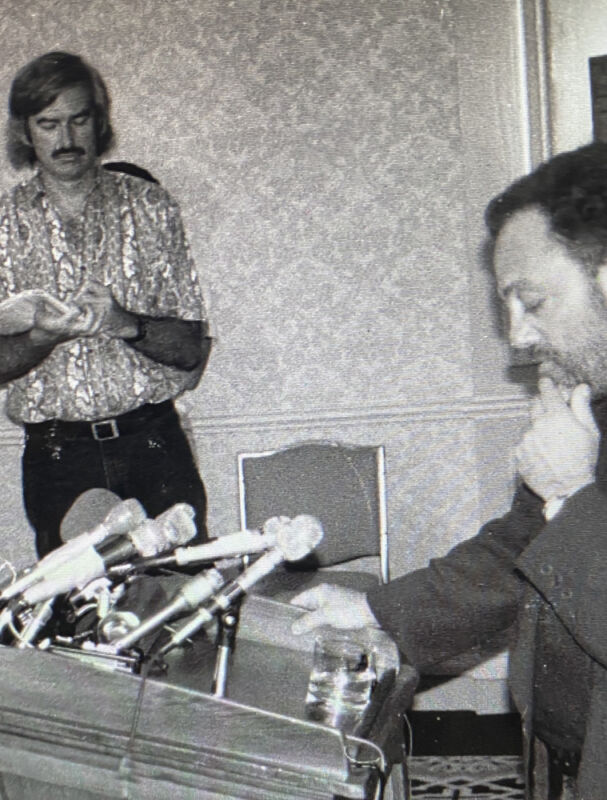

FREELANCE YEARS, BOSTON GLOBE MUSIC CRITIC, INTERVIEWS

After graduating from college in 1970, Steve pursued freelance music journalism on top of his teaching duties. His first taste came at PopTop. By 1975 he was freelancing for the Boston Globe, focusing on country and bluegrass performances (his debut show was Vassar Clemens and David Bromberg at Club Passim). In 1978, the Globe brought him on as a full-time music critic, a tenure that lasted for 28 years, many of those as senior pop music critic. When news broke that Steve was moving on from the Globe, U2’s Bono made his way to a late-night celebration in Steve’s honor at J.J. Foley’s in downtown Boston and toasted his many contributions to the world of music.

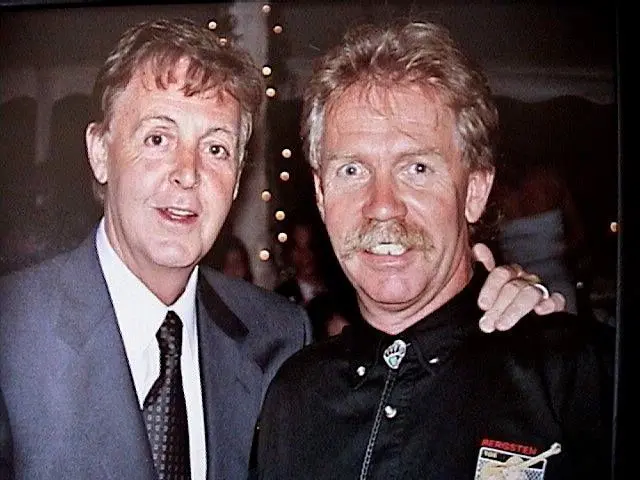

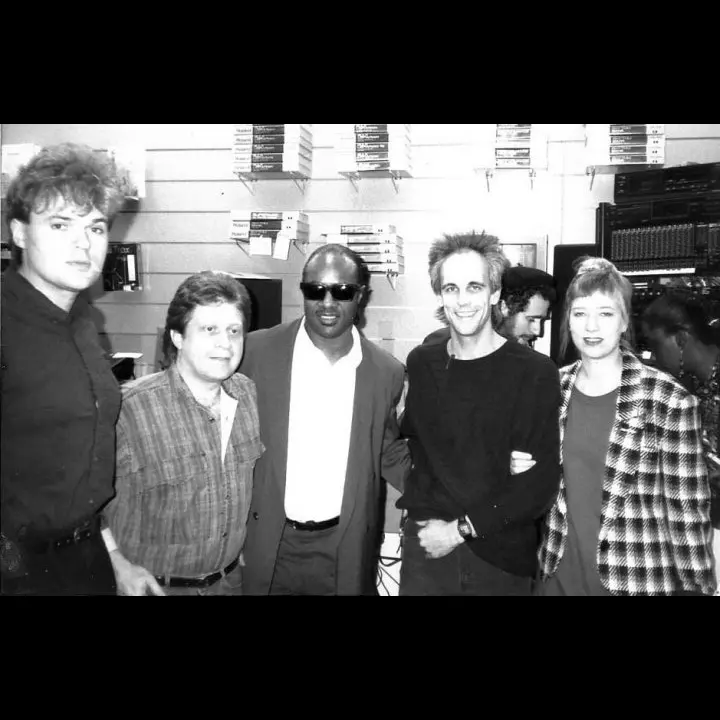

While Steve did countless record and concert reviews, his first love has always been the art of the interview. As he pointed out once, “In a concert or album review, you’re an observer. In an interview, you’re a participant.” To read the list of artists whom he has interviewed is to walk the floors of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The Stones, Springsteen, Petty, U2, Bonnie Raitt, McCartney, Stevie Wonder, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Bob Marley. (Ask Steve to tell you the story of the Bob Marley interview at the Essex House in New York City, on the 11th floor, Marley’s posse, ganja, soccer balls and the Book of Revelations. In that order. I’m not kidding).

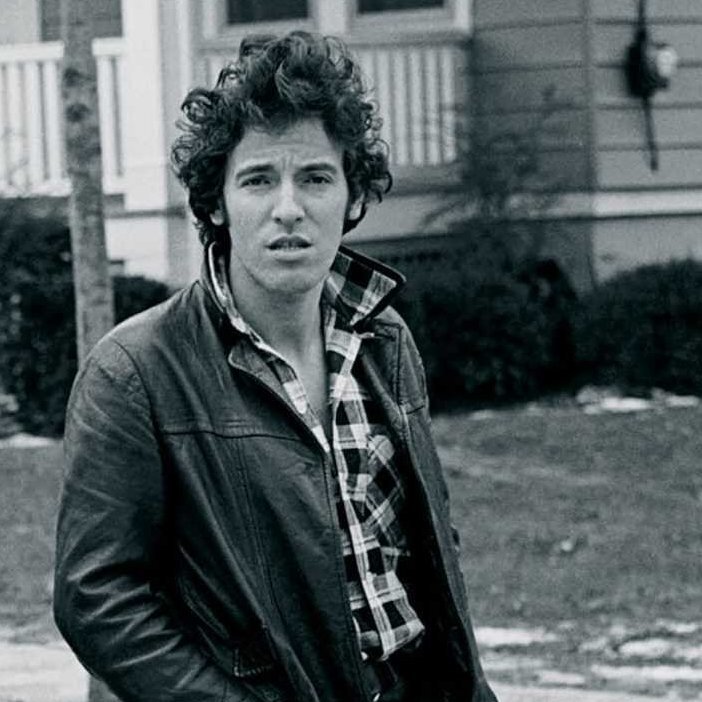

Steve felt that the secret to a good interview is to be prepared – do your homework, be familiar with their catalogue, have a few ice-breaker questions ready to go – but also be flexible. Be ready to both guide and follow the interview itself. Oh, and don’t ask questions about their love lives. The interview is going to reflect the artist. One of Steve’s favorite (and frequent) interview subjects was Keith Richards. “Everything with Keith is out in the open,” he said. “He’s totally unguarded.” Another favorite was Bruce Springsteen (“Always open, honest, straight forward”), The smartest? Paul Simon (“A total musicologist. He can go deep into Doo Wop, African Pop, Brazilian jazz, you name it”). On the “more challenging” scale, Mick Jagger (“He’s very guarded). On the quiet side, Tracy Chapman, Dave Matthews, Van Morrison.

The most different from his stage persona, said Steve, is Iggy Pop. “Here’s a guy who is a complete wild man on stage, who essentially invented crowd surfing, who’d end a show bleeding and battered,” he said. “But when I interviewed him at his hotel once and greeted him by saying, ‘Hello, Iggy,’ he corrected me with ‘My name is Jimmy Osterberg, call me Jimmy!’ And he turned out to be the nicest person in the world!”

BERKLEE HISTORY COURSE, ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME COMMITTEE

After stepping back from his full-time role at the Globe, Steve continued to do occasional freelance assignments for the paper. For over 10 years he taught an online course (which he also wrote) on the history of rock music for Berklee College of Music. It being an online course, his students cover a broad range of ages and nationalities. It was Steve’s goal to fill gaps in their familiarity with the most impactful artists of the genre and to share the historical and cultural backdrop that fueled the artistry.

Underscoring the respect that Steve enjoyed among his peers, he served seven years on the nominating committee for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, joining industry legends like Jann Wenner, Jon Landau, Ahmet Ertegun, Steve Van Zandt and Phil Spector. He felt good about being the first to nominate AC/DC but said it “bothers him to no end” that he was thwarted several times in his bid to get The J. Geils Band inducted.

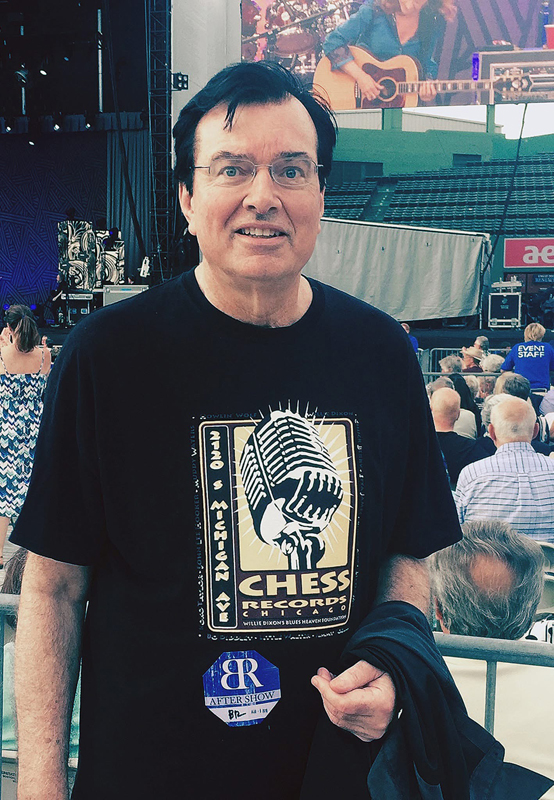

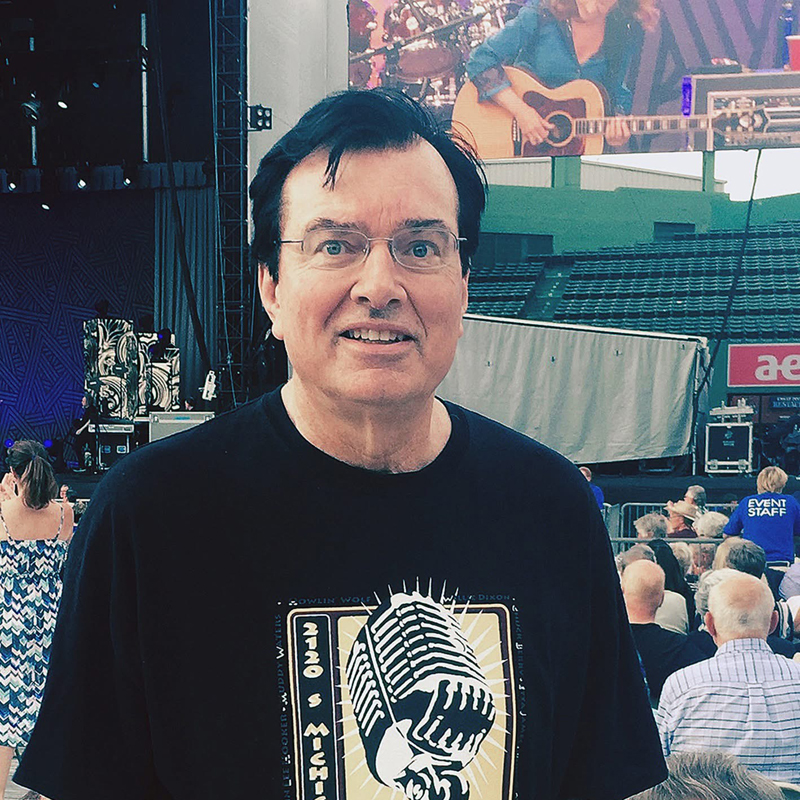

CAREER REFLECTIONS, DEATH

Looking back on his career, Steve expressed gratitude above all. ”I’ve been in the right place at the right time,” he said. “I’ve participated in the glory days of the newspaper industry, the music industry and the Boston music scene. I love the live music most of all; it’s the lifeblood of rock ’n’ roll and always has been.”

For decades, his routine was seeing 250 shows a year; when he was going through a divorce, it went up to 300. He chronicled the explosion of New England’s biggest ‘70s acts like Aerosmith, J. Geils, The Cars and Boston. He pointed to a contemporary band like Lake Street Dive, who have moved from the clubs in Cambridge to the concert halls around the world, as bearers of that tradition.

Steve covered a broad swath of musical styles from rock to reggae, from country music legends to local singer/songwriters. He was a tireless advocate for music coverage at the Globe and a booster of home grown musicians and the city’s music venues. All of this he saw as having been his privilege. “I’ve had a blessed career,” he told me. “Beats a real job.” He said that with a chuckle, but he knew that the job was certainly real and he practiced it in its highest form. And both the biggest names in the business and the members of the Boston music scene agree that his career has indeed been blessed.

Consider, for instance, this take on Steve’s place in the Boston musical firmament from the widely sought-after guitarist Duke Levine. “Steve is like the benevolent Godfather of the Boston music scene. He’ll hit three or four local artists’ shows on any given night. He’s passionate about so many in our scene, generous with enthusiastic praise, and invested enough to offer constructive criticism when he thinks it will help the cause. He’s always been ready to help with liner notes for our records, or write a feature story about us whenever possible. A true mensch!” A true mensch indeed. We were lucky to have him.

Steve died on October 26, 2024 in Care Dimensions Hospice in Lincoln, Massachusetts, less than two weeks after being diagnosed with cancer. He was 76 and had lived in Cambridge for many years. “With no disrespect to other critics, I think that when the musical world thinks of Boston in terms of a critic, they think of Steve Morse,” said Don Law, the chairman of Live Nation New England, as quoted in The Boston Globe. “He was the premier music critic of this region.”

(by Chuck McDermott)