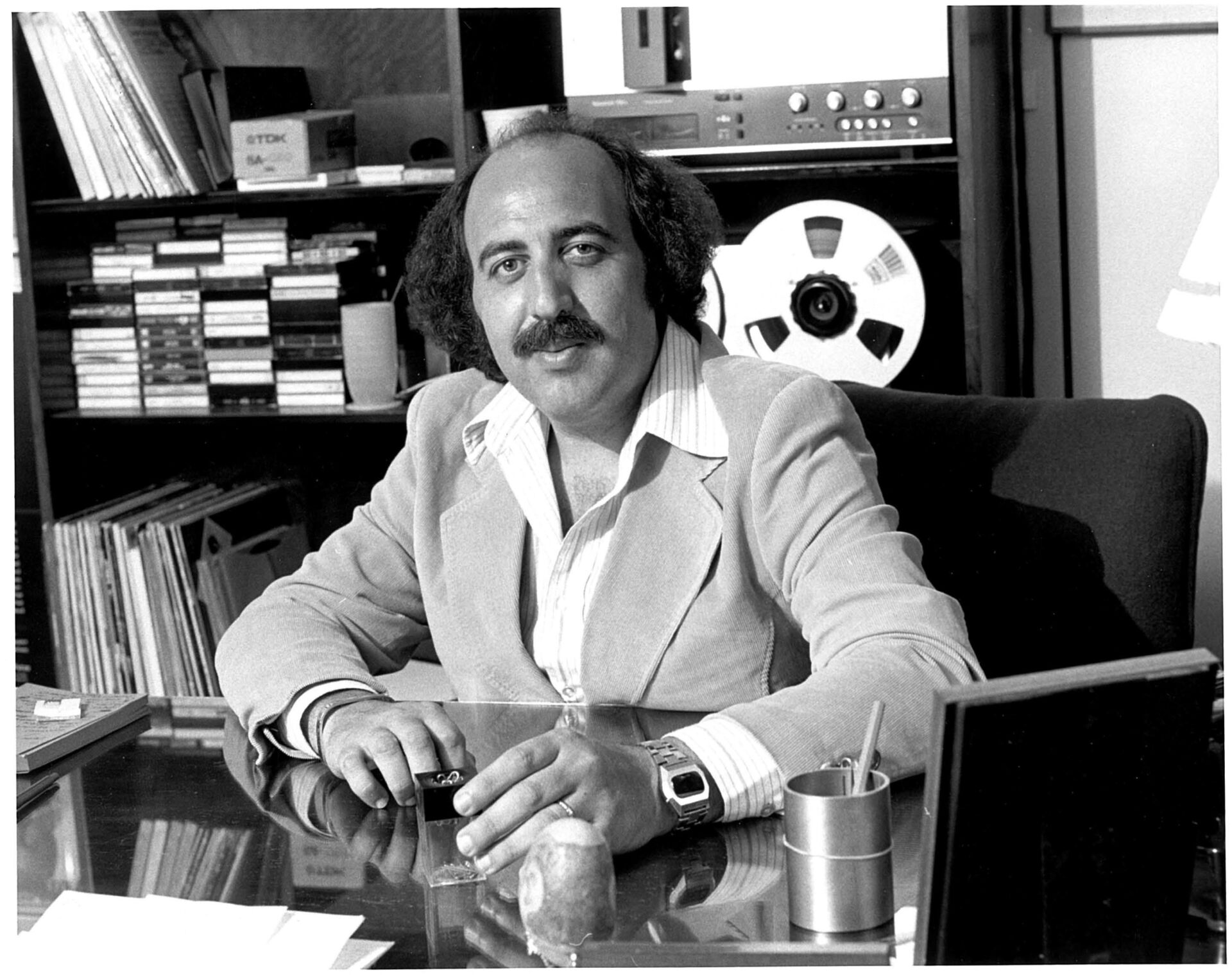

Shelly Yakus

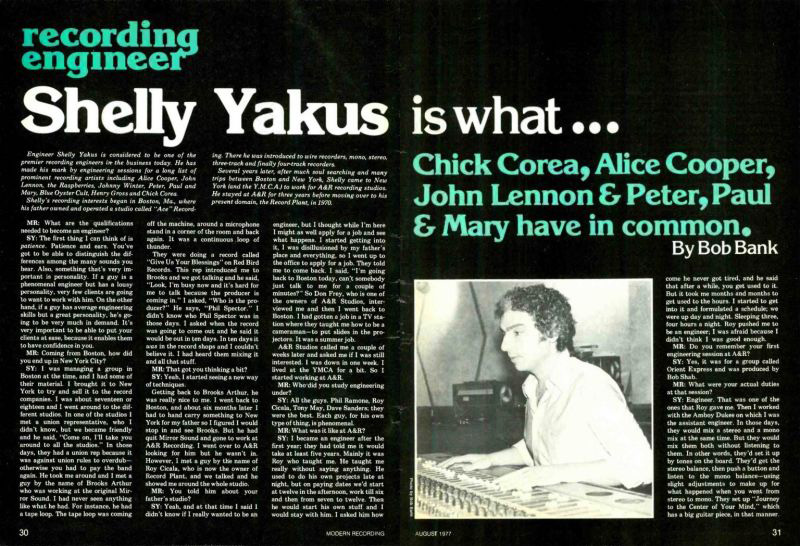

When it comes to a person’s chosen career path, the never-ending nature-versus-nurture debate often leans heavily to one side or the other; someone was either “born” or “raised” to” pursue a certain profession. But for Shelly Yakus, the blend was a bona fide balance of both across the board – figuratively and literally.

All evidence indicates that the world-renowned audio engineer was both born and raised to do one thing, and to do it at a level very few others have ever achieved: record music. A music lover by nature for as long as he can remember, Yakus was nurtured to a large degree within the soundproofed walls of New England’s first full-service recording space, Ace Recording Studios, established in 1946 by his father and uncle, where he spent countless hours from around age 10 and started cutting his teeth behind a mixing desk in his early teens.

Revered as one of the most gifted, skillful and technically forward-thinking sound engineers, mixers and studio designers in music-biz history and for an apparently innate musicality that helps him transform artists’ creative visions into acoustical realities – “it’s the ear, not the gear,” he says – Yakus has engineered, mixed and mastered tracks by a laundry list of luminaries. In a nutshell, his resume reads like a megastar-studded listing of artists who’ve defined – even redefined – rock, pop, R&B, soul, blues and jazz for the past 60-plus years including John Lennon, Van Morrison, Aretha Franklin, Lou Reed, B.B. King and Chick Corea.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, FORMATIVE STUDIO EXPERIENCES

Sheldon “Shelly” Yakus was born in Boston and lived in Dorchester until age five, when his family moved to Quincy. He graduated from Quincy High School in 1963 and, though never drawn to becoming a musician himself, listened to a wide variety of records while growing up, with bandleader/comedian Spike Jones’ albums and Ray Charles’ 1960 rendition of “Georgia on My Mind” being among his favorites.

At age 16, while sitting beside his father at Ace, Yakus had an experience that he calls “the foundation for everything to come” because it taught him the difference between “hearing” and “listening” to music. “My dad was spot-checking some 7½-inch copies with a Wollensak machine [a popular ‘60s-era reel-to-reel recorder],” he explains. “After playing one of them, he says, ‘Did you hear that?’ I said, ‘No,’ so he played it again. Still I didn’t hear it. Finally, after about 10 minutes, he points his finger when it happens. Still I didn’t hear it!

“Then, suddenly I hear this dropout. Very subtle and minute, but it was there. The sound didn’t go away but – just for a moment – it dropped in volume. So, I asked, ‘Was that there every time you played it?’ and he said, ‘Every time.’ I was shocked since I realized then how much I didn’t know. Everything changed for me because after that I started listening to everything in a different way. In those 10 minutes, I went from being a person who couldn’t hear a dropout to one who did. Before that, I was hearing but I was not listening.”

In 1966, Yakus started making regular trips to Decca Records in New York City, since the label occasionally did mastering and made pressings for Ace. On one visit, he had another formative experience when he happened to meet musicians’ union rep Max Rubefogel, whose job was to monitor studio overdubbing – which was against union rules unless musicians were paid – and thus had access to every studio in the city. When Yakus mentioned that he’d love to visit some studios, Rubefogel was happy to help that very day, taking him to Bell Sound, A&R Recording and Mirror Sound.

“Watching Brooks Arthur, the engineer at Mirror Sound, was an amazing lesson on how creative those New York engineers were,” he says. “For example, he ran a tape loop – something I’d never seen before – from the tape machine around a mic stand about 30 feet away with thunder-and-lightning sound effects. I asked why it was so long and he said it was so when he moved the volume fader up and down, there’d be no chance of hearing that same thunder and lightning twice while mixing.”

A&R RECORDING

A few months later, Yakus returned to Decca and stopped by Mirror Sound to see Arthur, not knowing that he’d recently moved to A&R. When he went to see him there, he met two other key personnel, engineer Roy Cicala, future owner of The Record Plant (and “the man who became my mentor,” he says), and Don Fry, the studio’s manager. Yakus applied for a job and two months later got the phone call that changed his life: he was hired.

In mid-1967, at age 21, Yakus left Boston to be an assistant at A&R. “Engineering was the only thing I knew and wanted and the studio was where I wanted to be,” he says, noting that he never considered staying at Ace because “there really wasn’t a place for me to grow.” And he realized immediately that his new home was a far more demanding environment than his hometown. “The big difference was that producers really didn’t demand anything from the engineers in Boston,” he says. “But in New York, if you didn’t deliver what they wanted to hear, you were out of a job.”

DIONNE WARWICK, BURT BACHARACH, HAL DAVID, “ALPHIE”

On one of his first days in the studio, Yakus worked with Phil Ramone, co-founder of A&R, on a Dionne Warwick session produced by Burt Bacharach and Hal David featuring a 35-piece orchestra; Bacharach played a seven-foot Steinway in the middle of the room while Warwick sang in the vocal booth. One of the three songs they recorded that day was the Bacharach/David-penned classic “Alfie,” which reached #15 in the Billboard Hot 100 and #5 in the Billboard R&B Singles chart that year.

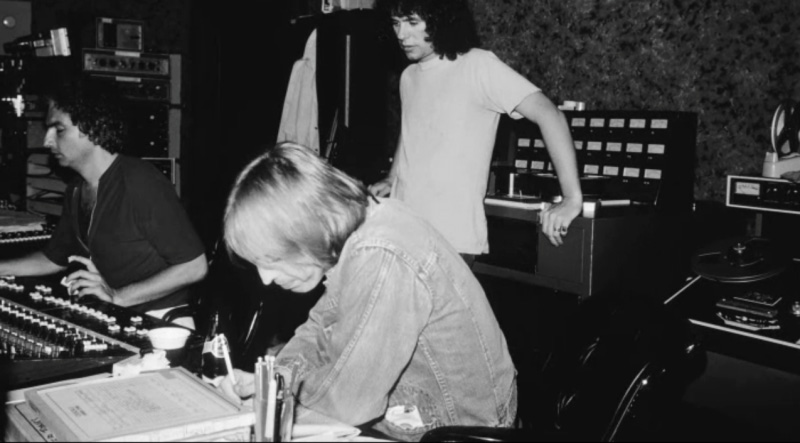

BECOMING LEAD ENGINEER, MUSIC FROM BIG PINK, MOONDANCE

Although A&R told Yakus it would take “at least five years” for him to become an engineer at the company, after working alongside Cicala and other engineers for about 12 months he began manning the board himself. “Roy pushed me to be an engineer. I was afraid because I didn’t think I was good enough,” he says. “It took me months to get used to the hours since I slept only about three or four hours a night. As an assistant, I’d start at 8:00, setting up for a large orchestra, record from 10:00 till 1:00, do a different setup for a different session and record till 6:00, then rock and roll from 7:00 till the sun came up.”

During his nearly three-year tenure at A&R, Yakus worked as an engineer on two of the era’s most iconic albums, The Band’s Music from Big Pink (1968) and Van Morrison’s Moondance (1970) and was an assistant engineer on discs by Frank Sinatra, Dionne Warwick, Peter, Paul and Mary and Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons, among others.

THE RECORD PLANT, JOHN LENNON

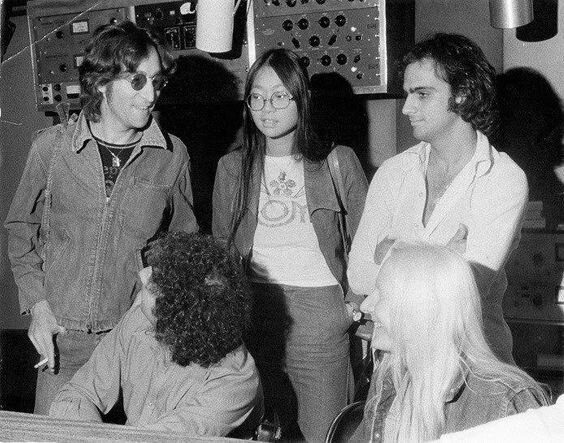

In 1970, Yakus moved to The Record Plant, where he stayed for the next 10 years and recorded and/or mixed albums and singles for a jaw-dropping list of acclaimed artists including John Lennon, working as one of the engineers on three of his solo LPs: Imagine (1971), Walls and Bridges (1974) and Rock ‘n’ Roll (1975).

”So there I am, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder at the console with John Lennon,” he says about his first sessions with the rock legend. “And I’m thinking, ‘Here’s one of the biggest artists ever, a Beatle who’s worked with George Martin and Geoff Emerick in some of the greatest studios in the world. Is he gonna figure out that I don’t know what the hell I’m doing?’”

While at The Record Plant, Yakus also recorded sessions for Patti Smith, Lou Reed, Alice Cooper, Booker T. & the M.G.’s, Aretha Franklin, Judy Collins, Chick Corea, Three Dog Night, Blood Sweat & Tears, The Ramones, Raspberries, Grand Funk, Johnny and Edgar Winter, Rick Derringer, Blue Öyster Cult, Paul Stookey and Warren Zevon, among others.

JIMMY IOVINE, TOM PETTY, DIRE STRAITS, STEVIE NICKS, A&M

Outside of his Record Plant role, he partnered with producer Jimmy Iovine on albums by Joan Jett, Golden Earring, Meatloaf and Graham Parker and chart-topping LPs including Tom Petty’s Damn the Torpedoes (1979, US #2), Dire Straits’ Making Movies (1980, UK #4) and Stevie Nicks’ Bella Donna (1981, US #1).

In 1985, three years after his profile was included in Who’s Who in Rock Music (Scribner, 1982), Yakus joined A&M Records in Los Angeles and he, Iovine and A&M co-founder Herb Alpert assembled a team of audio professionals to redesign five of the label’s studios and one production room over the following three years.

From 1985 to 1995, he was chief engineer and vice president of A&M Studios and engineered and/or mixed albums/singles for U2, B.B. King, Joe Cocker, Stan Getz, Cher, Eurythmics, Belinda Carlisle, Lone Justice, Herb Alpert, Suzanne Vega, Don Henley, Eric Carmen, Cutting Crew, Amy Grant, Terence Trent D’Arby, Joan Armatrading and Bob Seger, among others.

TONGUE AND GROOVE STUDIOS, R&R HALL OF FAME NOMINATION

From 1997 to 2002, Yakus was a partner at Philadelphia-based Tongue and Groove Studios, where he recorded and mixed albums for singer-songwriter John Hiatt and many others. In 1999, U2 frontman Bono nominated him for inclusion in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame but he was not inducted since engineers were not part of the Hall’s “non-performer” category at that time.

AFTERMASTER HD AUDIO, PROMASTER SOFTWARE

In 2006, Yakus began developing high-end video booths with Studio One Media, which became AfterMaster Audio Labs and Recording Studios a few years later. He brought AfterMaster his ideas, teamed with them and co-invented AfterMaster HD Audio and ProMaster, an online mastering software that produces fullness and clarity which the company claims is unachievable through traditional mastering techniques.

The patented technology if featured on tracks including Janet Jackson’s “Make Me” (2009), Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” (2009) and Donna Summer’s “To Paris With Love” (2010) – each of which reached #1 in the Billboard Dance Club Songs chart – and is used in the Bella Signa AfterMaster chip and the AfterMaster and HearClear TV boxes. ProMaster was the world’s first instant online music-mastering service and the online site ReverbNation has used the software to remaster millions of songs recorded by independent artists.

COMMENTS ON ENGINEERING QUALIFICATIONS, “PERFECT” RECORDINGS

Asked about the most important qualifications for an audio engineer, Yakus echoed his lifelong “it’s the ear, not the gear” philosophy but also highlighted patience and personality. “Patience, because you’ve got to be able to distinguish the differences among the many sounds you hear,” he said. “And personality, because if a guy is a phenomenal engineer but has a lousy personality, then very few clients will want to work with him. On the other hand, if a guy has only average engineering skills but a great personality, he’s going to be very much in demand.”

Asked if he always shoots for perfection when recording, Yakus said “perfection” has never been his goal per se. “The difference between ‘lousy’ and ‘good’ is easy to hear, but the difference between ‘good’ and ‘great’ is a fine line because ‘good’ is not good enough,” he said. “And that’s essentially what we’re talking about here: the difference between ‘good’ and ‘great.’ Many people say to me, ‘I want this to be perfect’ and I always tell them that we can try to make it ‘great,’ yes. But ‘perfect’? No. That’s boring.”

(by D.S. Monahan with thanks to Lennie Petze)