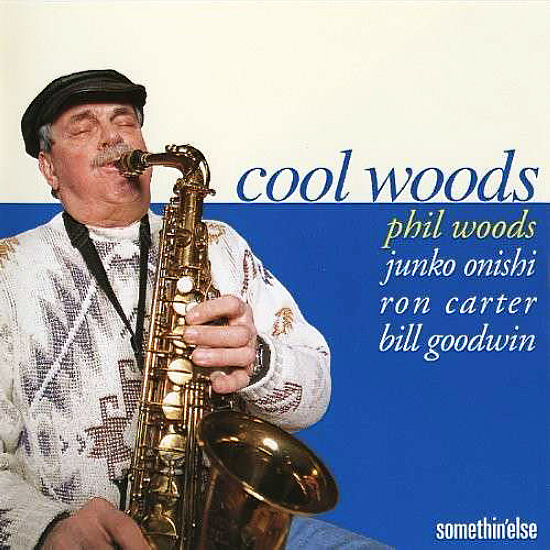

Phil Woods

The folklore, repeated by jazz writers going back to Leonard Feather in 1960, is that Phil Woods was introduced to the alto saxophone when he inherited a gold-plated model from his uncle, a mortician. Woods himself told a different tale, however.

According to Philip Wells Woods, born November 2, 1931 in Springfield, Massachusetts, he was fondling the instrument after his uncle died because he planned to “melt it down” and make a “golden horde of warriors” out of it, to go along with his other toy soldiers. He was only 12 years old, and this seemed “more fun” than learning to play the thing, he once said. The instrument sat in a closet for weeks until his mother persuaded him to give it a try rather than attempt such a risky metallurgical experiment.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, EARLY GROUPS/GIGS

Woods accordingly called The Drum Shop, a local music store, and signed up for a lesson with Harvey LaRose. When he asked whether he should bring his saxophone to the lesson, LaRose told him that would be a good idea. After the first lesson, LaRose said he knew that Woods was “faking the hell out of it” when he played, but the music teacher kept Woods on the straight and narrow path to mastery of the instrument, scolding him when he didn’t try out for the concert band at Springfield Technical High School. Woods tearfully promised to try out the next day, and “fell in love with orchestral playing.”

The Tech Tigers, as the school’s band was called, played sophisticated big band arrangements including “Music Maker” from the Harry James book and “Southern Fried” by Erskine Hawkins. While still in high school, Woods began working with groups in Springfield including Carmen Ravosa & His Rhythmaires, Frankie Smolkowich’s kid band, and what Woods called “a little bebop gang” that he formed in 1947 with Dave Brubeck’s future drummer Joe Morello and others.

Woods’s first gig with a “real orchestra” was a YMCA dance with musicians from the band at the Westover Air Field (in nearby Chicopee and Ludlow). Morello then got Woods his first steady gig, six nights a week at a club called The Blue Grotto. He began to explore the South End of Springfield, which was then “the Black section of town.” It was there that Woods played at a club called Phono Village, which he called “my real school” because “I was there every available minute, soaking up that blues feeling and learning tunes.” There he checked out musicians such as vibraphonist Prince Buddha, who was reputed to have cut Lionel Hampton in a jam session and experienced something he said he “hadn’t seen before…not like the average New England ofay experience.”

MOVE TO NEW YORK CITY, NOTABLE COLLABORATIONS

In 1948, Woods, Morello and bassist Chuck Andrus from Holyoke went to work with pianist Flip Brenner at a local restaurant/dance hall and Brenner arranged for an audition in New York City with a “big-time, cigar-smoking booking agent.” To impress the empresario, the band added various novelty touches to their act; for instance, they “donned football helmets and did a medley of college songs.” The group wasn’t hired, but Woods had seen the bright lights of the big city; he had been introduced to the new sounds of bebop by pianist Hal Serra, an older Springfield high school classmate, and with Serra’s guidance he began to make period forays into New York. “Springfield had given me all it could,” he would reflect later; he viewed New York as “the city which at that very moment was being invaded by the new leaders of the jazz revolution…It was time to bite the Big Apple.”

Following Serra’s example, he began by taking instruction from modernist pianist Lennie Tristano for $10 a lesson. He financed his education by working as a carpenter’s helper in his father’s sign business and playing five nights a week at the Springfield Elks club, a gig arranged by his uncle Phil Markley, a Massachusetts state representative. In 1949, 18-year-old Woods moved to New York City full time with Serra, Chuck Andrus and guitarist Sal Salvador, and began to take clarinet classes at the Manhattan School of Music. He soon soured on that school and transferred to The Juilliard School, from which he received a bachelor’s degree in 1952, majoring in clarinet because at the time the school did not offer a saxophone major.

In the mid-‘50s, Woods played with Richard Hayman, Charlie Barnet, Jimmy Raney and George Wallington before leading groups of his own. In 1956, Quincy Jones invited him to accompany Dizzy Gillespie on a world tour sponsored by the US State Department; he would later tour Europe with Jones, and in 1962 he toured Russia with Benny Goodman.

CHARLIE PARKER COMPARISONS, MARRIAGE TO CHAN PARKER

Woods was often compared to Charlie Parker, as were altoists such as Sonny Stitt, Gene Quill and Cannonball Adderley (all of whom were referred to at times as “The New Bird”). Woods invited more scrutiny in this regard than the others, however, because he married Parker’s long-time companion Chan and became stepfather to the couple’s daughter Kim. In Woods’s case, the comparison was both unfair and inapt; while he could bop with the best, he didn’t (and doesn’t today) sound like a Bird clone.

Woods’s relationship with Chan was by his account a happy one, even though she sometimes irritated him by recalling her times with Parker. “He’s gone,” Woods would say when she brought up her past life, “Now it’s me.” Woods resented the implication that he married Chan because of her connection to Parker, particularly the flip suggestion by fellow alto Art Pepper in his autobiography Straight Life that he didn’t know whether Woods pursued her “because he loved her or because she was Bird’s old lady or to get [his] horn or what. Hahaha!” In addition to Chan’s daughter by Parker, the couple had two children of their own, a son (Garth Daryl) and a daughter (Aimee Francesca).

DEATH, LEGACY

On September 4, 2015, at the age of 83, Woods played a concert of music from the album Charlie Parker with Strings in Pittsburgh with his oxygenator close at hand. When he finished, he put down his saxophone and announced “This is my last gig. I’m going to retire.” Twenty-four days later, he was dead of complications from emphysema.

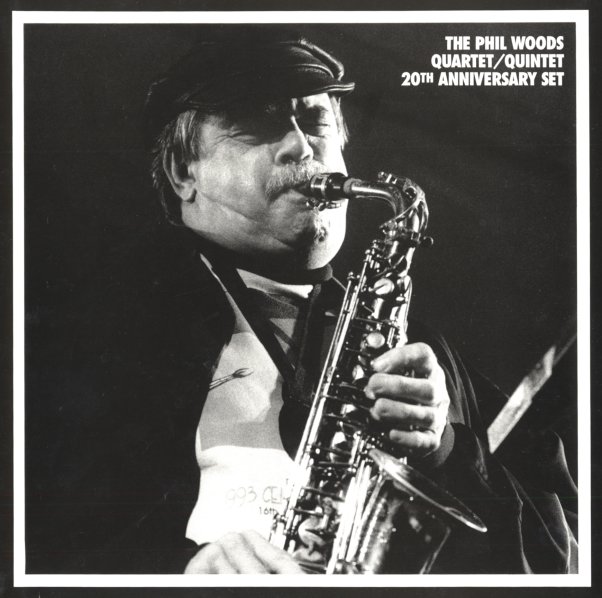

While largely forgotten today, Woods consistently topped polls ranking alto-sax players during his career, and his quintet was named the top small combo several times. He can be seen in the 2005 documentary Phil Woods: A Life in E Flat – Portrait of a Jazz Legend, and his biography, Life in E Flat, gives one a sense of a life lived hard, but without regret.

You have probably heard Woods’s music even if you didn’t know it; his most famous gig as an unidentified sideman is undoubtedly his solo on Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are,” but he also played with Steely Dan and Paul Simon. If you’re a film fan, Woods is heard on the soundtracks of The Hustler, the gritty poolroom drama starring Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason, and the avant-garde film Blow Up, by Michelangelo Antonioni. Woods had artistic skills beyond reed instruments; he composed and sang (poorly) a tribute to fellow alto Johnny Hodges on his 1991 album Flowers for Hodges, which included the following lines:

When I hear someone play

Alto sax the wrong way

I am tempted to say

Remember, Johnny Hodges

The Rabbit – my first habit.

I saw Woods only once, in the early 1980s, on a double-bill with Zoot Sims, who was the headliner on the jazz (and booze) cruises that once plied the waters of Boston Harbor. I had known Woods previously only by name, not having heard any of his recordings. He was in fine form that night, and while Sims at the time was my favorite living saxophonist, I regretted that I’d missed Woods’s first set below deck so as to keep my seat (and get another drink) for Sims’s second set topside. Woods was in his 50s then but still blowing like the young man from Western Massachusetts who moved to New York when he was in his teens.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (2023, Equinox Publishing), Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (2019, Oxford University Press) and the forthcoming Sax Expat: Don Byas (scheduled for publication in April 2025).