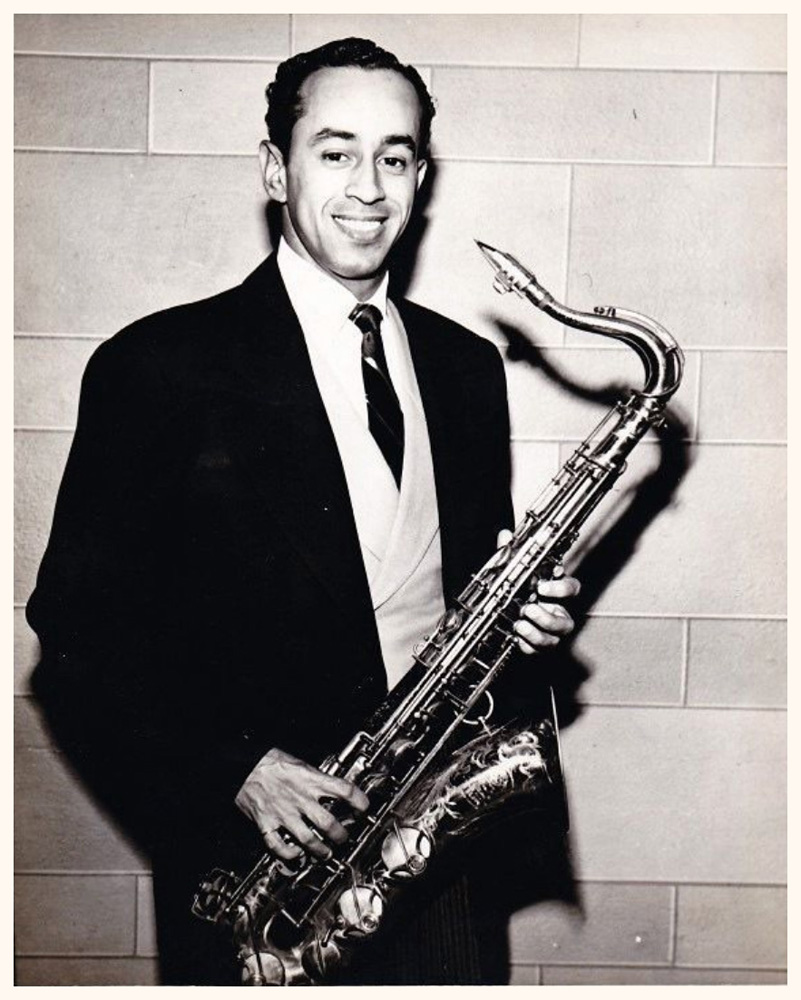

Paul Gonsalves

There are men who achieve at a high level over the course of a long career but are remembered for a single extraordinary feat; Willie Mays’ over-the-shoulder catch in the 1954 World Series is one such moment. In jazz, there is Paul Gonsalves, who is credited with reviving the career of Duke Ellington in 1956 with 27 choruses on a song he had played many times before.

Gonsalves was born July 12, 1920 in Brockton, Massachusetts (not, as is often claimed, in Boston). He was the fifth child of 13 born to John and Mary Gonsalves, both natives of Portugal of Cape Verdean descent, and raised in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, which then as now has a large Cape Verdean population. Gonsalves’s father taught him and two of his brothers to play guitar in the Crioulo style, a mixture of Portuguese and African influences. The boys formed a group that played for family affairs, but they viewed their services as a chore, not as a pastime. “I came to hate music,” Gonsalves would say later, “especially the humdrum kind we often had to play.”

Gonsalves had heard Duke Ellington’s band and similar ensembles on the radio, but he was not inspired to play jazz until he was 16 and saw The Jimmie Lunceford Band – with its star alto sax Willie Smith – at a midnight show in Providence. “From that time on I wanted to play saxophone, so I worried my father until he went out and bought me one,” a used tenor for $59. His sister Julia said “worrying” consisted of walking around the house miming the act of playing a sax until his father gave in, on the condition that Paul pay him a dollar week to reimburse him for the cost of the instrument.

NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY, EARLY GROUPS, SABBY LEWIS

Gonsalves told jazz writer Stanley Dance that he graduated from high school in 1938, but another public record indicates that he left after three years. He initially planned to study commercial art at Rhode Island School of Design on a scholarship but – like Ellington, who turned down an art scholarship to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in 1916 – instead took a job doubling on sax and guitar at a Providence nightclub. “It was my first professional job, in a tuxedo, playing from five in the afternoon to one in the morning,” he said.

Gonsalves received formal instruction at New England Conservatory from Joseph Piagetelli, who inspired him to practice for eight hours a day. After three years, Piagetelli told his student he had nothing more to teach him but recommended that he take another year to further his education. Gonsalves didn’t follow his teacher’s recommendation as to harmony and music theory, but he became sufficiently proficient on the clarinet to fool Ellington into thinking he was Barney Bigard when the legendary bandleader heard him playing one night from another room. After finishing his formal training, Gonsalves began to play professionally with Henry McCoy & The Jitterbugs in Providence; when that band broke up, he joined dance bands led by Phil Edmund, Duke Oliver and Henry McCoy in New Bedford, all of which included musicians of Cape Verdean descent. (Edmund would later record an album of Cape Verdean music, including a number that features a solo by Gonsalves.) Gonsalves moved from Providence to Boston and eventually joined the band of Sebastian “Sabby” Lewis, who featured the young tenor prominently.

COUNT BASIE, DIZZY GILLESPIE

Gonsalves joined the US Army in 1942. When he was discharged, he re-joined Lewis and began to be noticed as “the young tenor player at the Savoy in Boston” (he doubled on alto). In 1946, he received an offer to join Count Basie to replace Illinois Jacquet. In his autobiography, written with Albert Murray, the Count cited Gonsalves’s work on “Sweet Lorraine,” “Mutton Leg” and “Bill’s Mill” in particular. Gonsalves also organized (with four other band members) a Basie band softball team for which he played shortstop, but apparently not too well; “Paul was prone to miss a few catches,” said alto saxophonist Preston Love.

Gonsalves spent four years with Basie, then joined the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra in 1949. At the time, Jimmy Heath and John Coltrane played alto in the band, and they found themselves playing third fiddle to Gonsalves. “All the young ladies who came backstage didn’t care about me or Coltrane,” Heath recalled. “They wanted Gonsalves.” Gonsalves stayed with Gillespie until the band folded, then headed to New York City.

DUKE ELLINGTON, 1956 NEWPORT JAZZ FESTIVAL

Gonsalves was down to his last $7.20 when, on an impulse, he went to Birdland where, after a few drinks, he worked up the courage to say hello to Ellington. In his graciously cagey manner, Duke said, “Hey, sweetie, I’ve been looking for you. Why don’t you come down to the office tomorrow?” Ellington needed a tenor for a string of dates he had lined up, and auditioned Gonsalves. After playing two standards from the band’s book. Gonsalves heard Ellington say, “This so-and-so sounds just like Ben!” Gonsalves would later claim “I’ve got this job because I know all of Ben Webster’s solos.”

Gonsalves is best remembered today for his solo at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival on “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue.” At the time, the Ellington orchestra was at a low point in its history. On the night of July 7th they were consigned to a split shift, opening the day’s performances and closing out the night. Ellington told his men that once they got through a suite commissioned by festival promoter George Wein, they’d “relax and have a real good time” playing “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,” a work he composed in 1937 and which he’d been revising ever since. He had recently hit upon a new solution: have Gonsalves improvise in a blues mode with just the rhythm section.

When Ellington called “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,” Gonsalves pretended not to know which number the bandleader meant and Ellington, not taking any chances, made himself clear: “[I]t’s the one where we play the blues and change keys,” Ellington replied. “I bring you on, and you blow until I take you off.” After an uninspiring opening to the set, Ellington hit the keyboard aggressively with the opening vamp and Gonsalves followed with a succession of rocking choruses. The audience responded with enthusiasm and were soon in a frenzy common for rock ‘n’ roll crowds but unheard of at a jazz concert. In a wholesale re-assessment of Ellington’s career, Time magazine said his band was “once again the most exciting thing in the business.” Ellington himself put the transformation in semi-religious terms: “I was born in 1956 at the Newport Festival,” he would say.

The composition had been a regular part of Gonsalves’ repertoire for Ellington, so the suggestion that his explosive performance at Newport was spontaneous combustion is incorrect. “It was something everyone welcomes in a big band,” said fellow Basie tenor Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, “because it was something you could stretch out on, where the soloist is not restricted to one or two choruses.” George Avakian, who produced the live album of the concert, said “The Gonsalves solo is not really a solo at all, but a leading voice supported by many parts, the beat laid down by the drums, bass, and occasionally Duke’s piano.”

LATER ACTIVITY, DEATH

Like some musicians who yearn to break free from the strictures of their jobs in big bands, Gonsalves would occasionally play freelance gigs when he had a night off. “I heard Paul Gonsalves playing guitar in a New Bedford club a few years ago,” said fellow Basie tenor Frank Wess in 1965. In his book Boston Jazz Chronicles, Richard Vacca says Gonsalves could often be found “working for a night in a pickup band” in Jazz Corner, the neighborhood bounded by Massachusetts and Columbus Avenues.

Gonsalves was an erratic employee; his fondness for drink and drugs is apparent from film of the band in which he leans at a nearly horizontal angle, catching a nap when not playing his horn. Along with trumpeter Ray Nance, he was the leader of “a contingent of addicts” in the Ellington band who began to use heroin that came to be known as “The Air Force.” He was arrested along with Nance and two others for possession of heroin in Las Vegas, but released on probation.

Gonsalves died at the age of 53 on May 15, 1974 in London; the news was kept from Ellington, who was near death himself and died a week later. Gonsalves’s body was returned to the United States and, because he was an honorably discharged serviceman, he was buried in Long Island National Cemetery.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).