The Old Music Biz: An Artist’s-Eye View

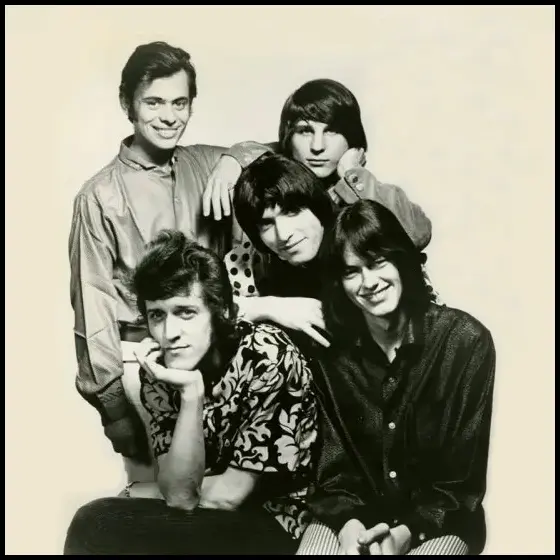

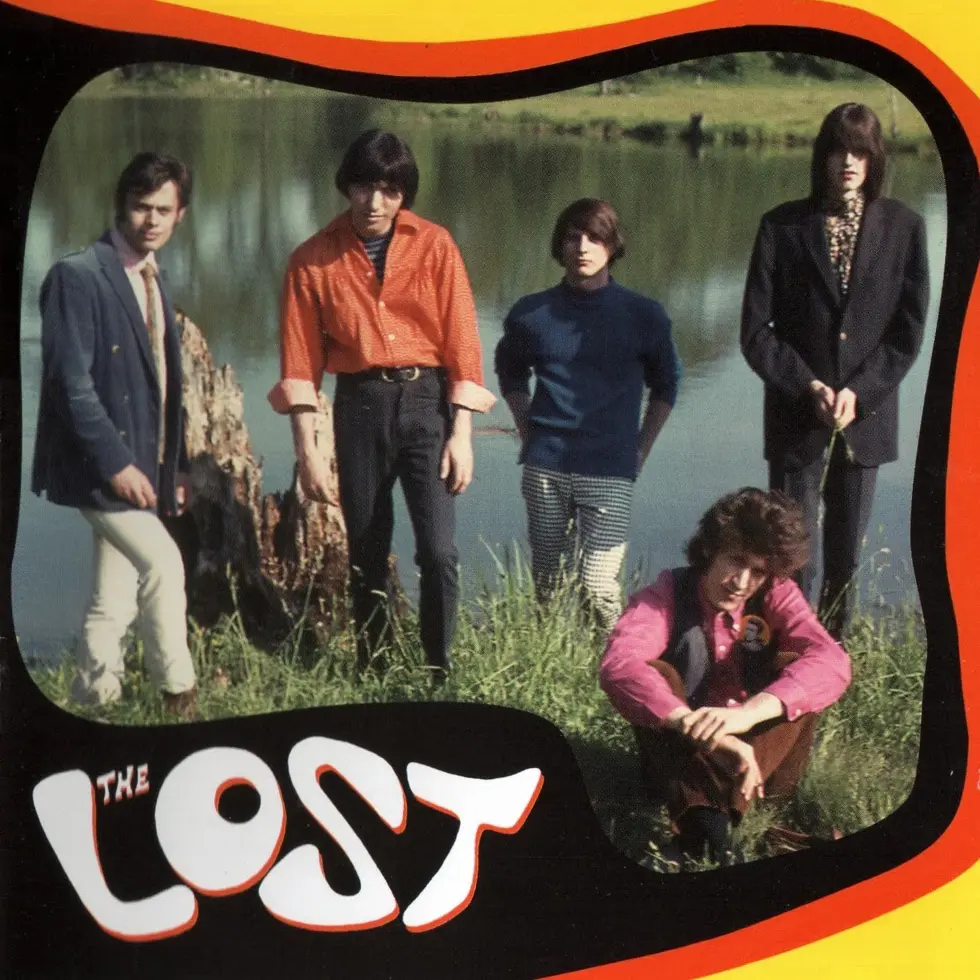

Ted Myers is a songwriter, musician and producer living in Los Angeles. He was a founding member, with Willie “Loco” Alexander and Walter Powers, of The Lost, one of Boston’s pioneering rock bands c. 1964-1967.

All through my career as a recording artist I was plagued with talentless and incompetent people messing with my work.

It seems to me, in the ‘60s especially, there were people in positions of power in the music business that knew nothing about the creative process, were not especially creative themselves, and yet professed to tell me, the artist, how to do my job. They all claimed to know what sells. The truth is, nobody really knows. I almost always knuckled under to them because my living depended on it. I was scuffling and scrounging to eek a living out of the music business and, as humiliating as it was, I had to go along to get along. It resulted in watered down and sometimes grotesquely altered versions of my songs. And it didn’t sell.

In 1965 my first band, The Lost, started recording for Capitol Records. Capitol had The Beatles and The Beach Boys, the two biggest rock groups in the world, so naturally we were thrilled. Surely they knew what they were doing. But the people we encountered seemed clueless about what to do with a nascent rock band who had no studio experience. We were clueless too, and so we did what we were told. In those days, the term “record producer” was not in common parlance. We were assigned an “A&R man” by the faceless men that ran the New York office of the record company. They had never heard us. Our A&R man, likewise, had never heard us before we showed up in Capitol’s New York Studio A to record our first sides. There were no demos, no pre-production, no reviewing and choosing the best songs. No discussion at all. That was all done by us, independent of the label. And, like I say, we were clueless. We were literally thrown into the deep end of the pool and told to swim. Today, when I hear the results of that first session, I shudder. The songs were not catchy or commercial, the sound was terrible, and our voices were inchoate. The nameless, faceless powers that be determined that none of those first three tracks, recorded in August 1965, were suitable for release. For once, they were right.

The next batch of tunes was recorded in September and October, and reflected our intense efforts to improve. But still there was no creative input from the A&R man. As I recall, he just sat in the booth with the engineer (an indifferent older guy, who didn’t appear to have any feel for rock ‘n’ roll) and say “Do it again” or “That’s a take.” The technology didn’t allow for much overdubbing, so we had to record all the instruments at once, and they didn’t know how to record loud guitars without them leaking into the drum track, so they kept asking us to turn down. The resulting sound was thin and anemic—not like we sounded live. In spite of this, the October session yielded two tracks the powers that be deemed worthy of being sides A and B of our first single.

We toured extensively in and around our home base, Boston, and across upstate New York. Our local promo man, Al Coury—one of the few Capitol guys we liked and trusted—worked the record hard, and we made a lot of local charts in New England and a few cities in upstate New York. Al was the one who got us the opening slot of The Beach Boys East Coast tour. That was in spring, 1966. But we had no follow-up single to our first single that had run its course by then.

In August, 1966—too late to capitalize on the Beach Boys exposure—Capitol released one more single. But we were unhappy with the recording, and convinced Capitol to pull it back. We recorded the same song again in a local Boston studio. The second version was way better but, since Capitol had already sent the first version to radio stations and then asked them NOT to play it, version two got no airplay. Shortly after that, we were dropped by the label. This fiasco was a result of the collective incompetence of us and the label. We had no actual management; nobody giving us well-informed career direction, no clear strategy at all that I can remember.

We recorded fifteen tracks for Capitol over a twelve-month period. Only four sides were ever released (counting the two on the aborted second single). In 1999, Lost devotee Erik Lindgren and I were, after ten years of trying, at last able to license all the Capitol tracks and release them on a CD on Erik’s label, Arf! Arf! There could’ve been a pretty good album in those tracks, but Capitol had a rule: if you don’t have a nationally charting single, you don’t get to do an album. And so our album remained in the can for more than three decades.

The Lost was well known and loved by many in the Northeast. But we were all nineteen and twenty years old, and mostly left to make all our own decisions, many of them not that wise. We hung on for another few months without a record deal and then disbanded.

In spite of all the bad decisions, The Lost was as close as I ever came to being a rock star, even though I went on to form and join four more bands, three of which landed major label record deals. I kept plugging away right up into the ‘80s.

It’s easy to blame other people for your own failures, but the bottom line is, I made a lot of bad decisions because I was motivated by desperation. Desperation to make a living and desperation to get my music out there—even if it was massacred by incompetent producers.

In the music business—like all the entertainment businesses—success or failure depends a lot upon luck. But maturity, focus and hard work are also essential. In retrospect, I find myself wanting in all three.