Newport Jazz Festival

Despite its tiny population of some 25,000, Newport, Rhode Island has a long history of hosting very big events. In 1881, the first US National Championship was held on the grass tennis courts at the Newport Casino; in 1895, the debut US Open and Amateur Championship took place at the Newport Golf Club; and from 1930 to 1983, Newport was the site of the America’s Cup.

But while those elite competitions are perfectly aligned with the seaside city’s reputation as a summer playground for the landed gentry – bolstered by its abundance of Gilded Age-era mansions – Newport hosts two world-renowned events celebrating something that rises above all economic and social barriers: music. Of the pair, the Newport Folk Festival is more broadly famous but the Newport Jazz Festival was first, founded five years before its singer-songwriter-centric counterpart. And for the past seven decades, it’s been the setting of epic performances, iconic recordings and – in 1960 and 1971 – mob violence and utter chaos.

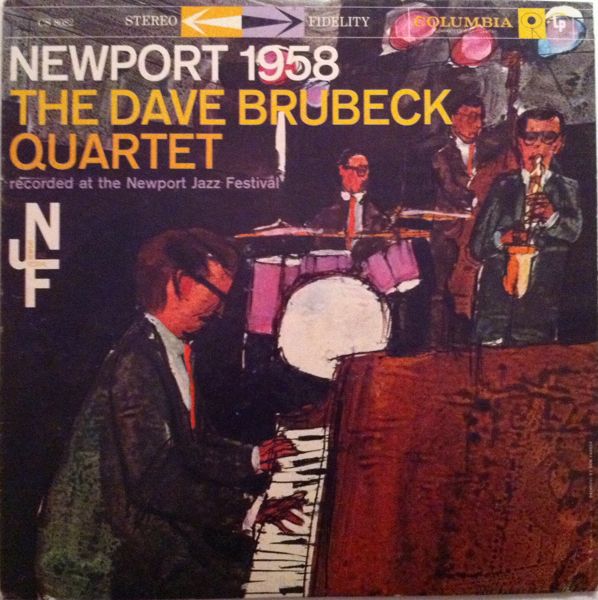

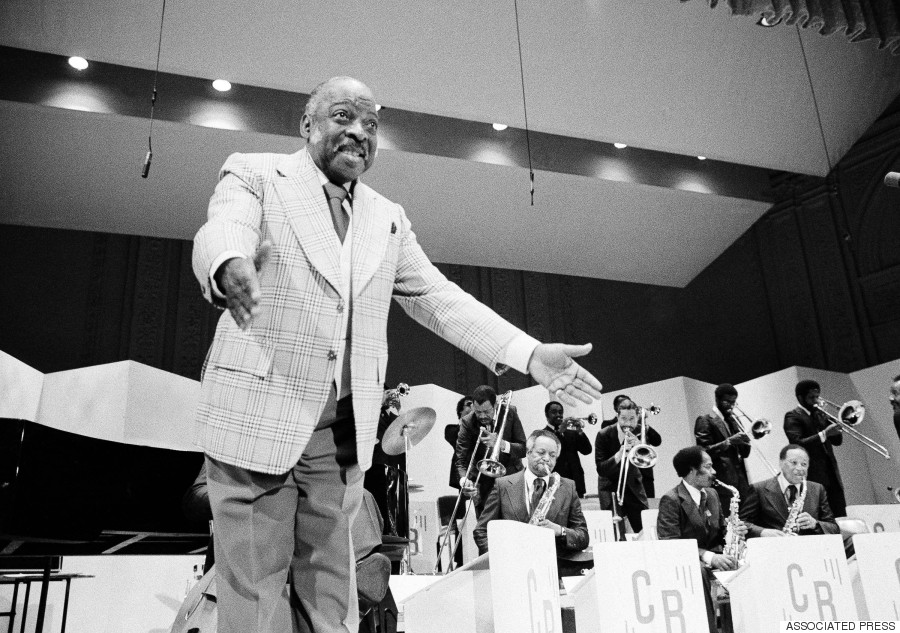

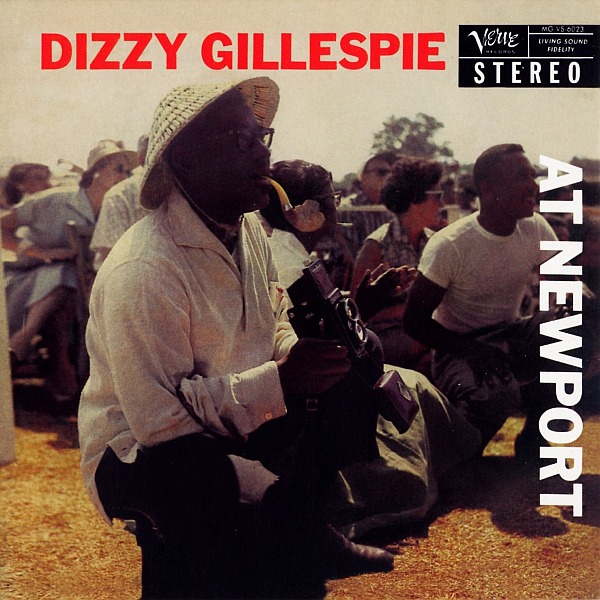

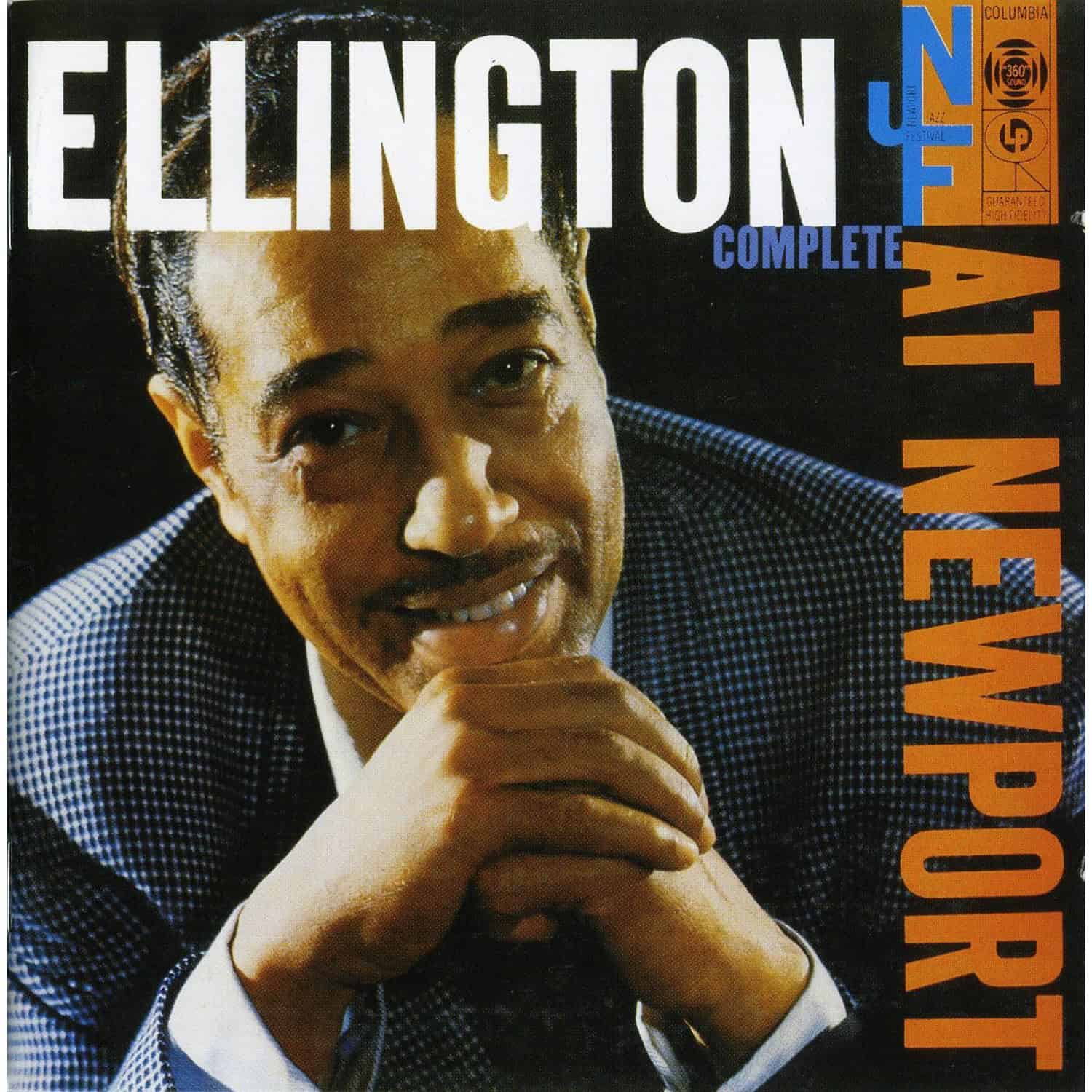

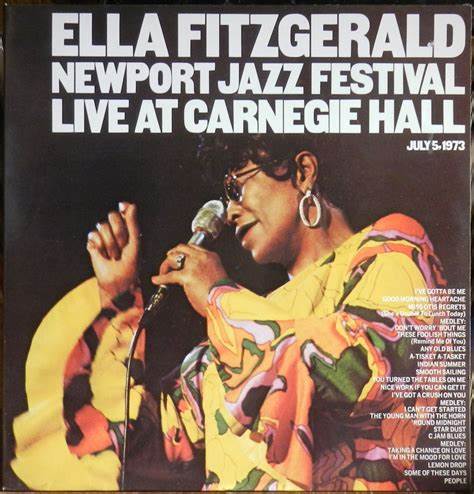

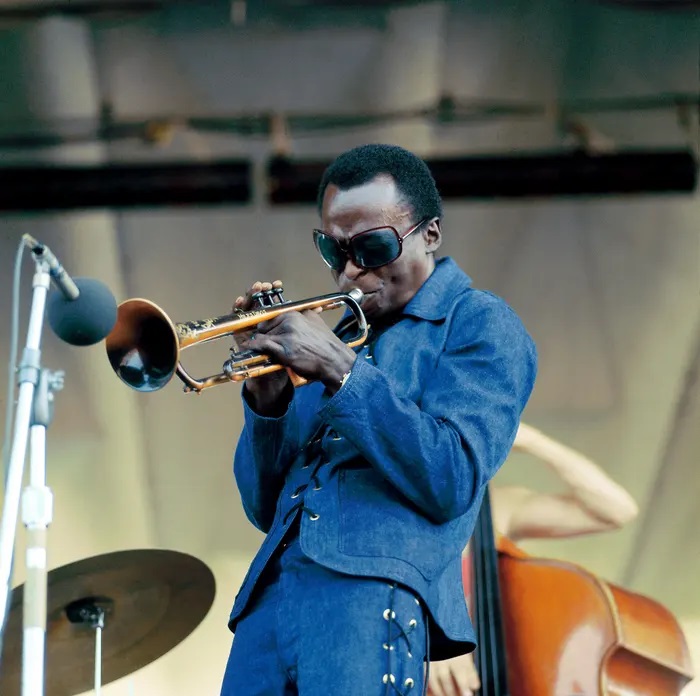

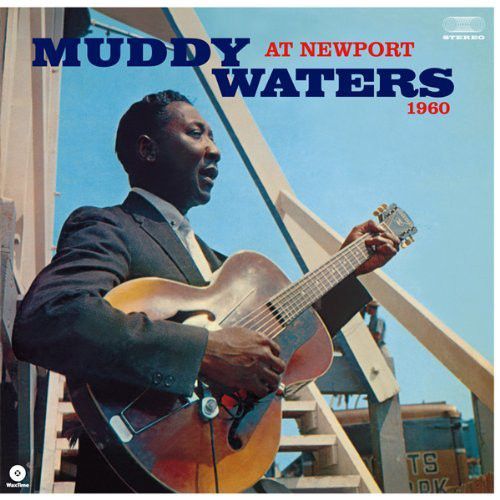

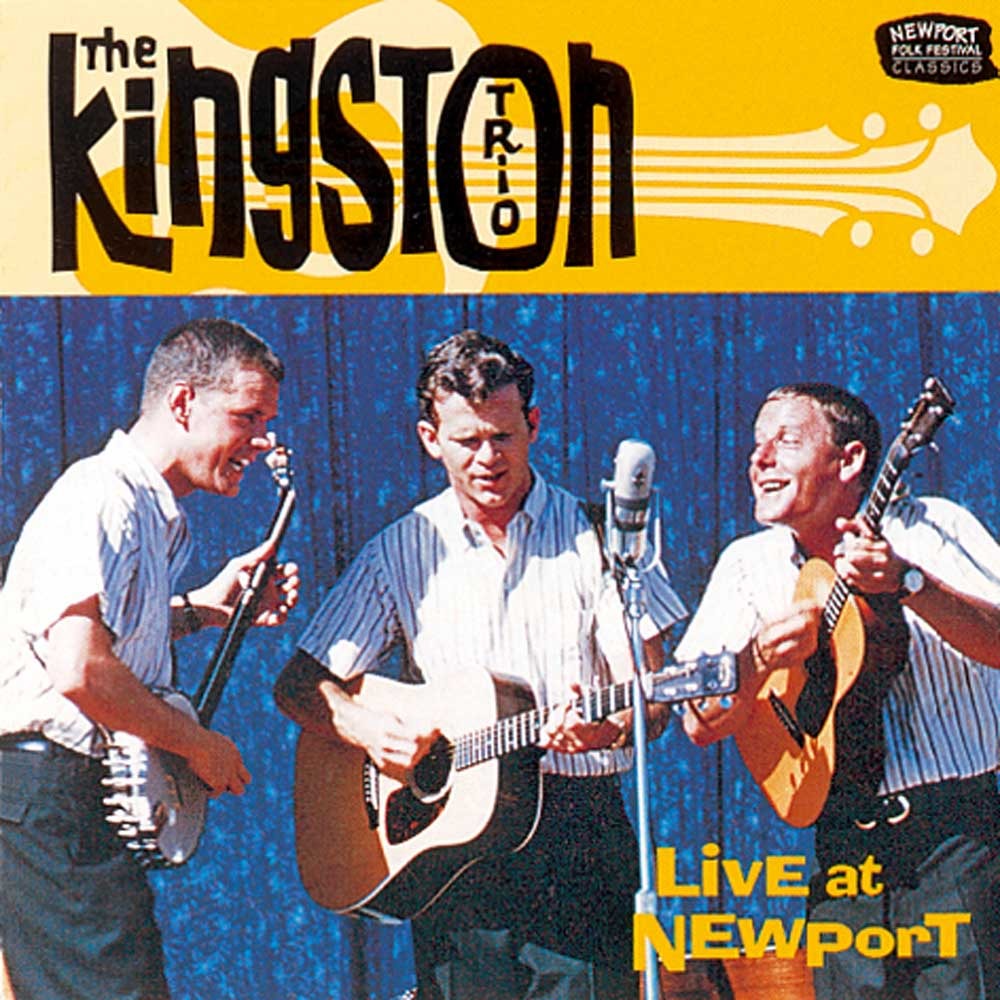

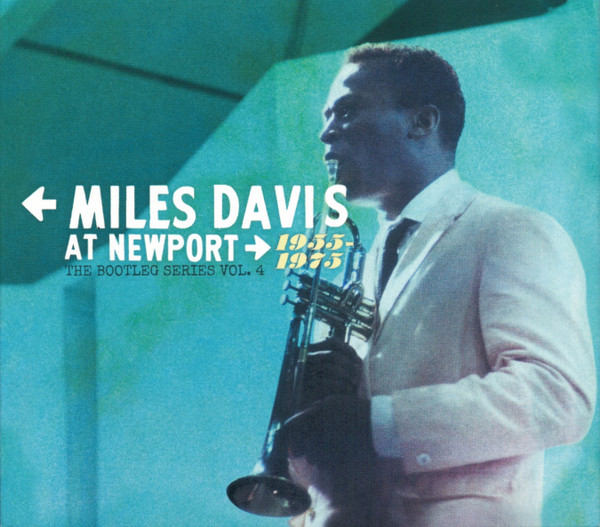

Dozens of official albums and boatloads of bootlegs have been recorded at the festival, including ones of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Muddy Waters, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Stan Getz and Miles Davis. In a 2023 piece headlined “Five Newport Performances that Changed Music History,” PostGenre magazine’s Editor-in-chief Rob Shepherd listed the appearances he believes have been the most significant: Miles Davis’ in 1955, Duke Ellington’s in 1956, Anita O’Day’s in 1958, The Kingston Trio’s in 1959 and Dave Brubeck’s in 1971. “These performances were more than mere sets,” he wrote. “They were events that changed the trajectory of modern music.”

BEGINNINGS, DEBUT EVENT

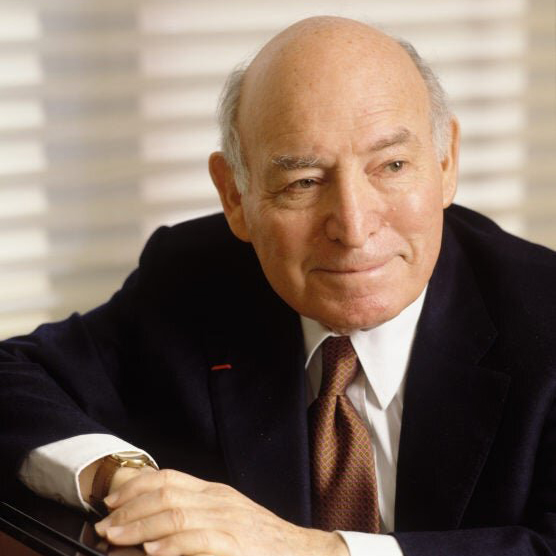

The Newport Jazz Festival was founded in 1954 by Newton, Massachusetts native George Wein, a Boston University graduate, World War II veteran and pianist who owned the jazz club Storyville, but calling it his “brainchild” would be misleading. As Wein was always quick to admit, the idea to hold the event was not his own.

The concept originated in 1952, when Newport socialite Elaine Lorillard, wife of tobacco heir Louis Lorillard, said she’d give him $20,000 (about $230,000 in 2023) to organize such a festival, saying she thought summers in the gilded community were “terribly boring.” Wein, who’d founded Storyville in 1950 at age 25, had never even considered holding a large-scale outdoor event but accepted in a heartbeat. “I had no rule book,” he once said. “I knew it had to be something unique, that no jazz fan had ever been exposed to,” adding that he wanted to “combine the energy of a jazz club in Harlem with the ambience of classical concerts at Tanglewood.” In other words, he sought to create something that no jazz fan – no music fan, period – had ever seen.

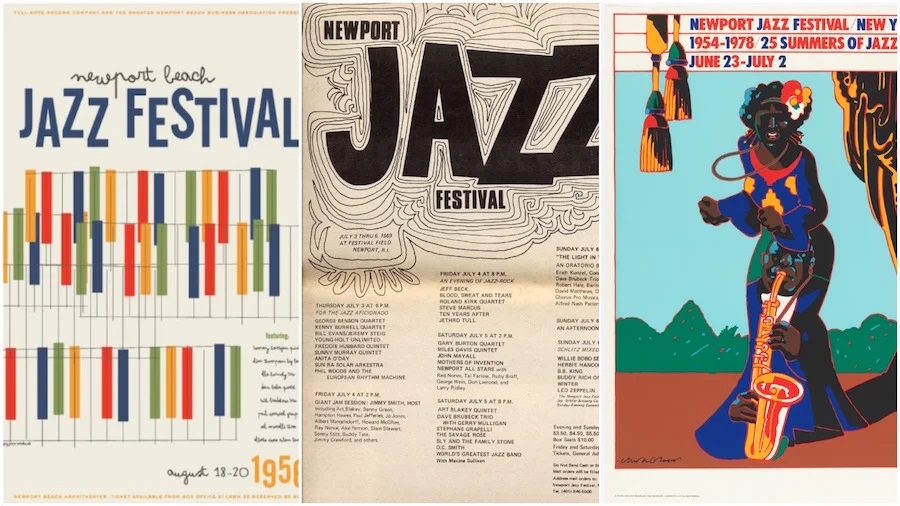

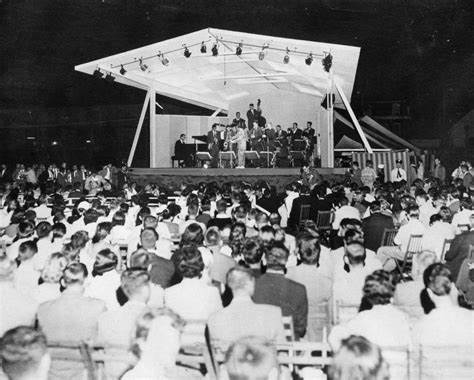

Nearly two years in the making, the debut event, billed as the First Annual American Jazz Festival, was held July 17 and 18, 1954, at the Newport Casino, emceed by pianist-composer-bandleader Stan Kenton. In addition to the performances, it included panels and discussions similar to those that had been held at Music Inn in Lenox, Massachusetts, since 1950.

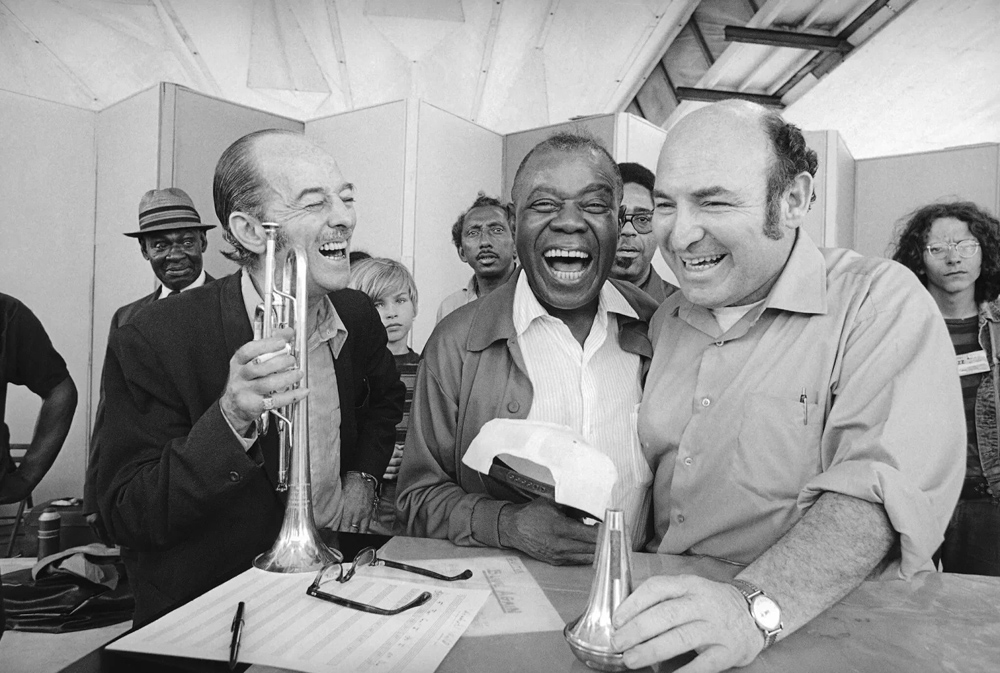

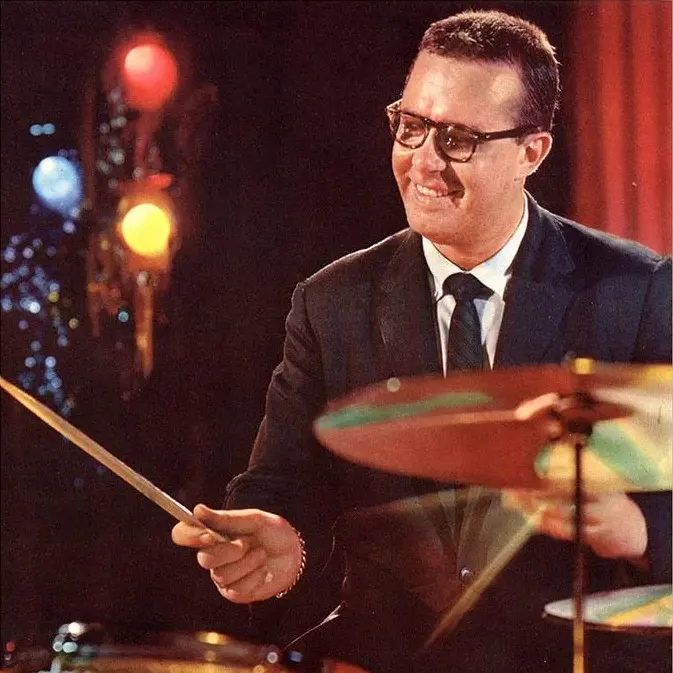

Though it rained buckets for much of the first day, the 13,000-strong audience seemed entirely unconcerned with the weather given the raft of top-tier talent Wein was able to attract thanks to his vast range contacts within the national jazz community. The bill included Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie, Lee Wiley, Eddie Condon, The Modern Jazz Quartet and Gerry Mulligan and Wein instituted a “rain or shine” policy that’s never changed. In the evening, the Lorillards hosted the musicians at their 9,800-square-foot mansion on Bellevue Avenue, Quartrel, where they mingled with Newport’s high society until the wee hours of the second day, when Oscar Peterson, Gene Krupa and George Shearing made appearances.

1955-1959, MILES DAVIS, MAHALIA JACKSON

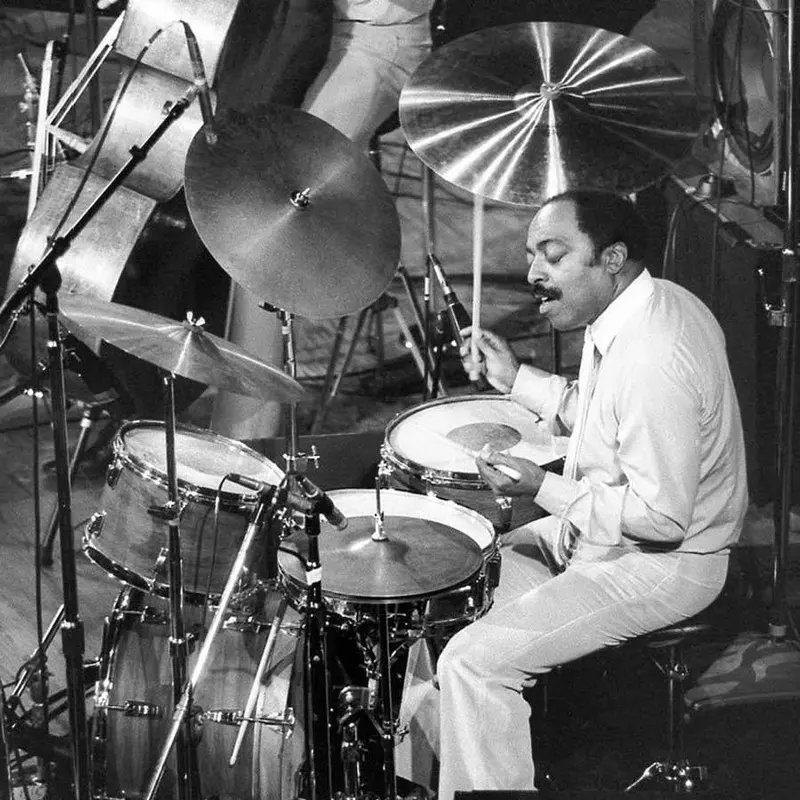

In 1955, the festival moved to Freebody Park since the Newport Casino refused to host the event again, saying its lawn and other facilities were not able to support it a second time. The Lorillards purchased a 50,000-square-foot mansion, Belcourt, in the hope that they could host the festival there but neighbors rejected the idea. Workshops and receptions were held at Belcourt, however, and Wein expanded the second festival to three days. Among those appearing were Count Basie, Erroll Garner, Woody Herman, Louis Armstrong, Dinah Washington, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, Max Roach and Clifford Brown. The second day included a set from George Wein’s All-Stars, who became a fixture at the event for the next six-plus decades.

Historically speaking, the defining moment of the 1955 festival came from Miles Davis who, having recently kicked a years-long heroin habit, practically demanded that Wein let him perform. Initially reluctant since many critics had written Davis off as just another washed-up junkie, Wein added the 29-year old to the bill and he took the stage with Thelonious Monk, Zoot Sims, Gerry Mulligan, Percy Heath and Connie Kay. Columbia Records producer George Avakian signed him to the label following the critically acclaimed set and, after Davis completed the last year of his contract with Prestige, Columbia released his albums ‘Round About Midnight and Miles Ahead in 1957, followed by 26 more over the next 32 years.

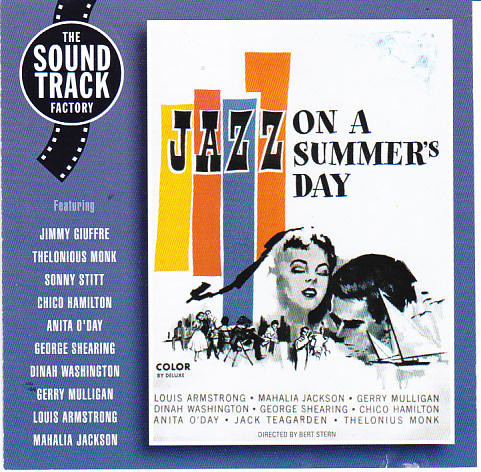

In 1956, Roy Haynes, Sarah Vaughn and Charles Mingus made their Newport debuts and in 1957 the most talked-about performance came from 55-year old Mahalia Jackson, who’d never appeared at a secular venue. The mainly white audience, virtually none of whom had ever heard gospel music sung with such passion, gave her a standing ovation and Jackson returned in 1958. In 1959, the festival’s name recognition grew exponentially with the release of Jazz on a Summer’s Day, a film featuring footage from the 1958 event.

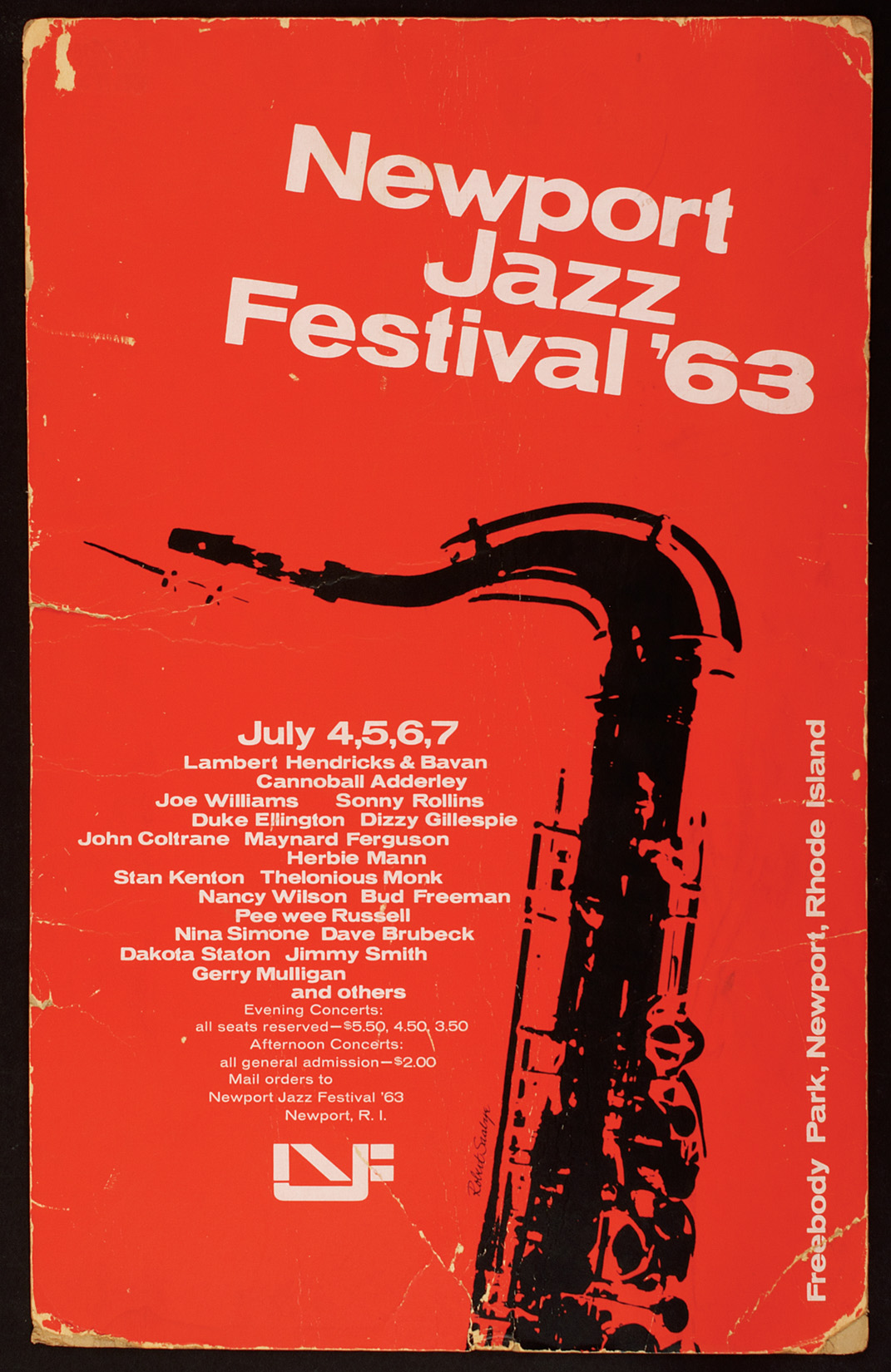

1960, MUSIC AT NEWPORT FESTIVAL, 1963-1968

By 1960, playing at the Newport Jazz Festival was de rigueur for every major jazz artist and copycat festivals began popping up across the US. As popular as the festival had become, however, that year’s event was marred by violence that resulted in some 200 arrests and prompted cancellation of the 1961 festival. The 1960 event was also notable for the presence of a rival one that Charles Mingus and Max Roach organized, held at the Cliff Walk Manor Hotel in Newport as a protest against the Newport Jazz Festival paying jazz innovators less than mainstream artists.

In 1961, promoter Sid Bernstein organized Music at Newport, a festival that was a financial flop but provided vocalist and Providence native Carol Sloane with her big break. When the Newport Jazz Festival resumed in 1962, Wein changed its tax status from a non-profit to a for-profit by establishing Festival Productions, Inc., and in 1965, the year Frank Sinatra made his Newport debut, the event moved to Festival Field.

1969: JAZZ, SOUL, R&B, ROCK

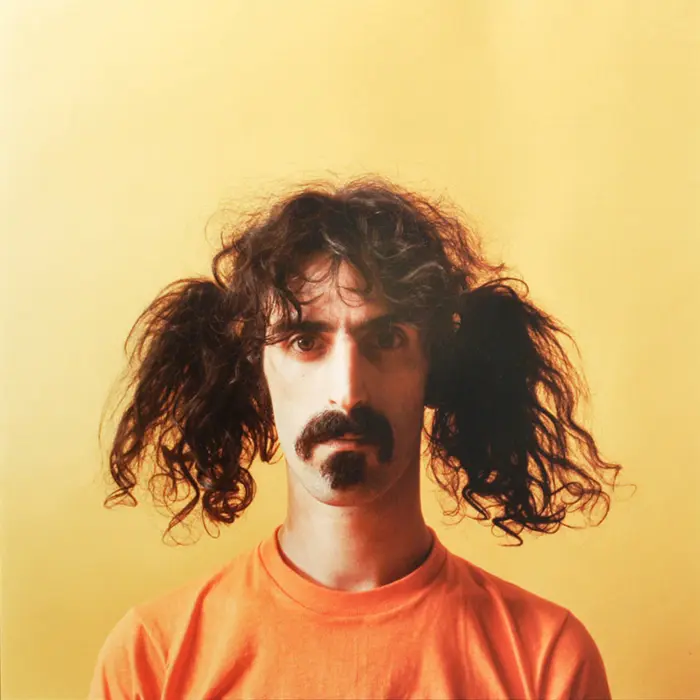

For the 1969 festival, which ran the month before Woodstock, Wein presented jazz, soul, R&B and rock. Artists included Sun Ra, Bill Evans, Sonny Stitt, Buddy Rich, Blood, Sweat & Tears, The Jeff Beck Group, Ten Years After, Jethro Tull, John Mayall, Sly & The Family Stone, Frank Zappa, James Brown, B.B. King, Johnny Winter and Led Zeppelin.

The weekend saw an estimated crowd of 50,000 sitting on a nearby hillside, some of whom surged against the fencing at times. On Sunday afternoon, in a clever effort to reduce the unruly mob, Wein had his people announce that the Led Zeppelin set scheduled for that evening had been cancelled; that wasn’t true, but the overflow crowd diminished and the band played as scheduled.

1970 FESTIVAL, 1971 RIOT

In 1970, the festival reverted to mostly jazz – “maybe too much rock” in 1969, Wein told Billboard magazine – but The Ike & Tina Turner Revue played the final set on the second day. The 1971 festival is the stuff of legend because it ended in a full-scale riot that resulted in the Newport Jazz Festival moving out of Newport for 10 years.

In addition to jazz and R&B acts, the 1971 bill included The Allman Brothers Band and, perhaps since there were no major rock festivals in the US that summer, an estimated 15,000-20,000 rock fans came to Newport to listen from outside Festival Field. On the second night, thousands broke through the eight-foot fence while Dionne Warwick was singing “What the World Needs Now Is Love.” As rioters lit fires and police rushed in, Wein tried to address the mob from the stage but to no avail. The remaining two days were cancelled and the Newport City Council revoked the festival’s license indefinitely.

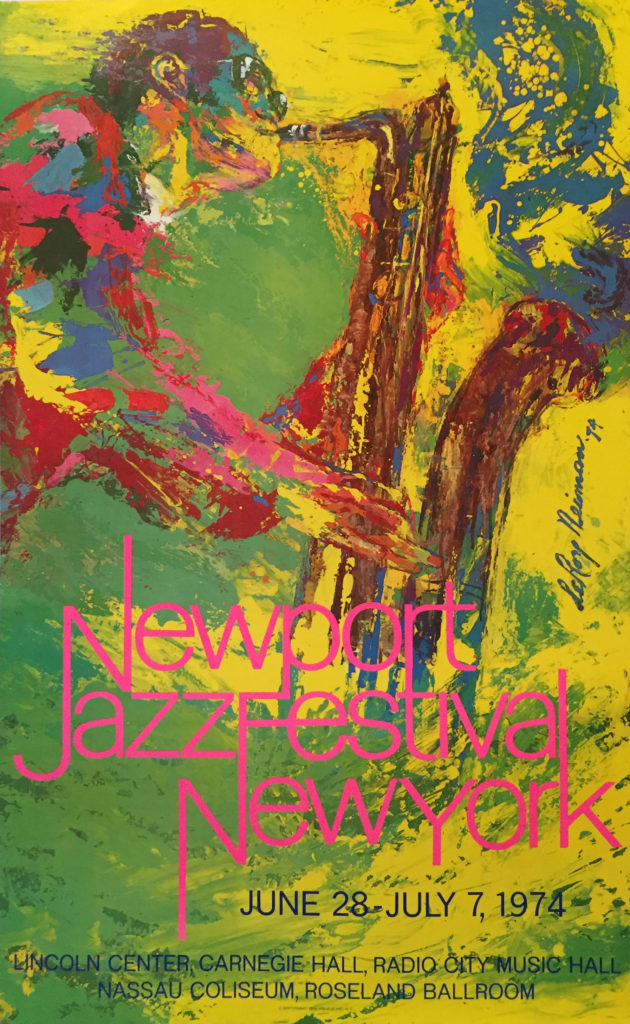

MOVE TO NEW YORK CITY, SARATOGA

In 1972, Wein relocated the event to New York City, renaming it the Newport Jazz Festival New York and splitting performances between Radio City Music Hall, Yankee Stadium, Philharmonic Hall and Carnegie Hall. For the first time, he took on a corporate sponsor and the event was billed as the Schlitz Salute to Jazz.

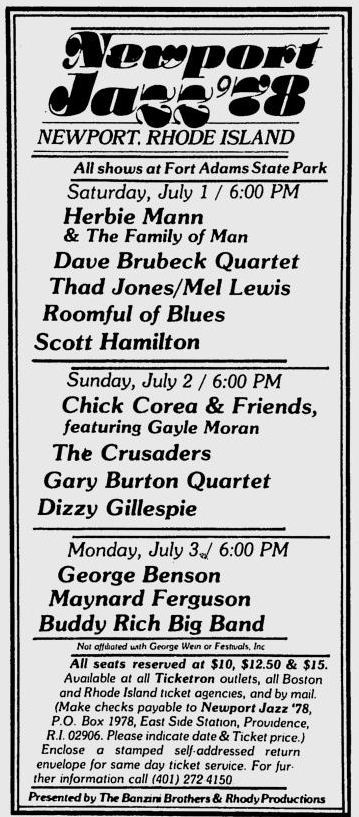

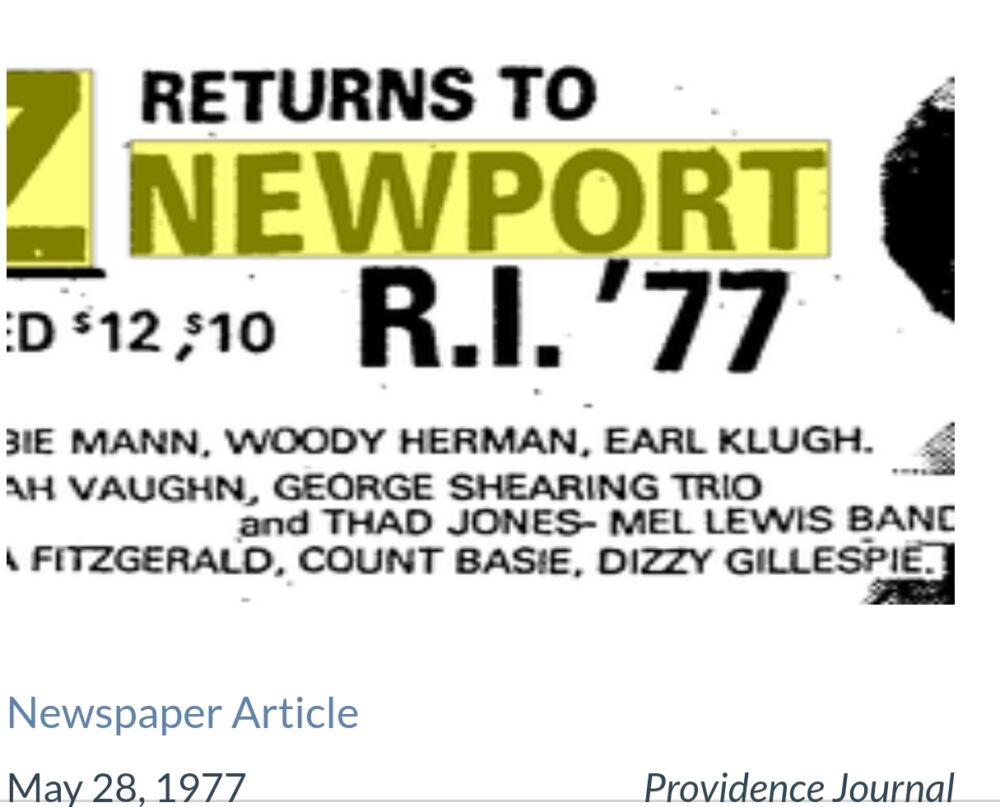

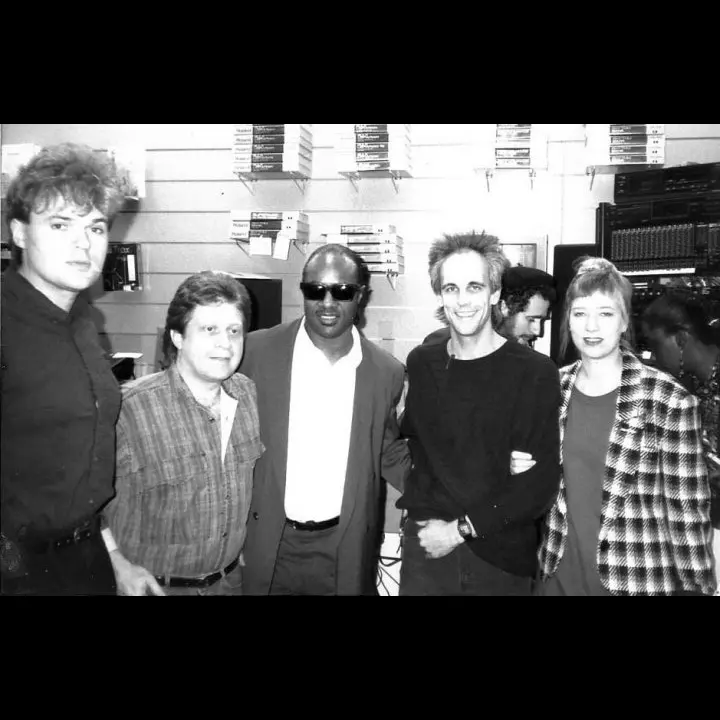

Throughout the decade, artists included jazz greats like Bennie Goodman and younger artists including Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, Freddie Hubbard, Stevie Wonder, Roberta Flack, Grover Washington Jr. and Diana Ross. In 1977, Wein established the Newport Jazz Festival Saratoga in Upstate New York (while continuing the New York City event and holding one in Newport) and for the 25th anniversary festival in 1978, he organized a mini-festival on the White House grounds and held one in Newport.

RETURN TO NEWPORT, 1980S, 1990S

In 1981, the festival returned to Newport as the Kool Jazz Festival; a separate event was held in New York City under the same name that year. Since then, it’s taken place in Newport only, at the 10,000-capacity Fort Adams State Park. In 1984, Japanese electronics giant JVC became the main sponsor; the event was called the JVC Jazz Festival until 2009.

During the 1980s, while there were plenty of traditional acts on the bills, the trend was toward fusion groups like Spyro Gyra and “smooth jazz” players such as David Sanborn and Wynton Marsalis. Artists from other genres took the stage, including blues-rock guitar extraordinaire Stevie Ray Vaughan.

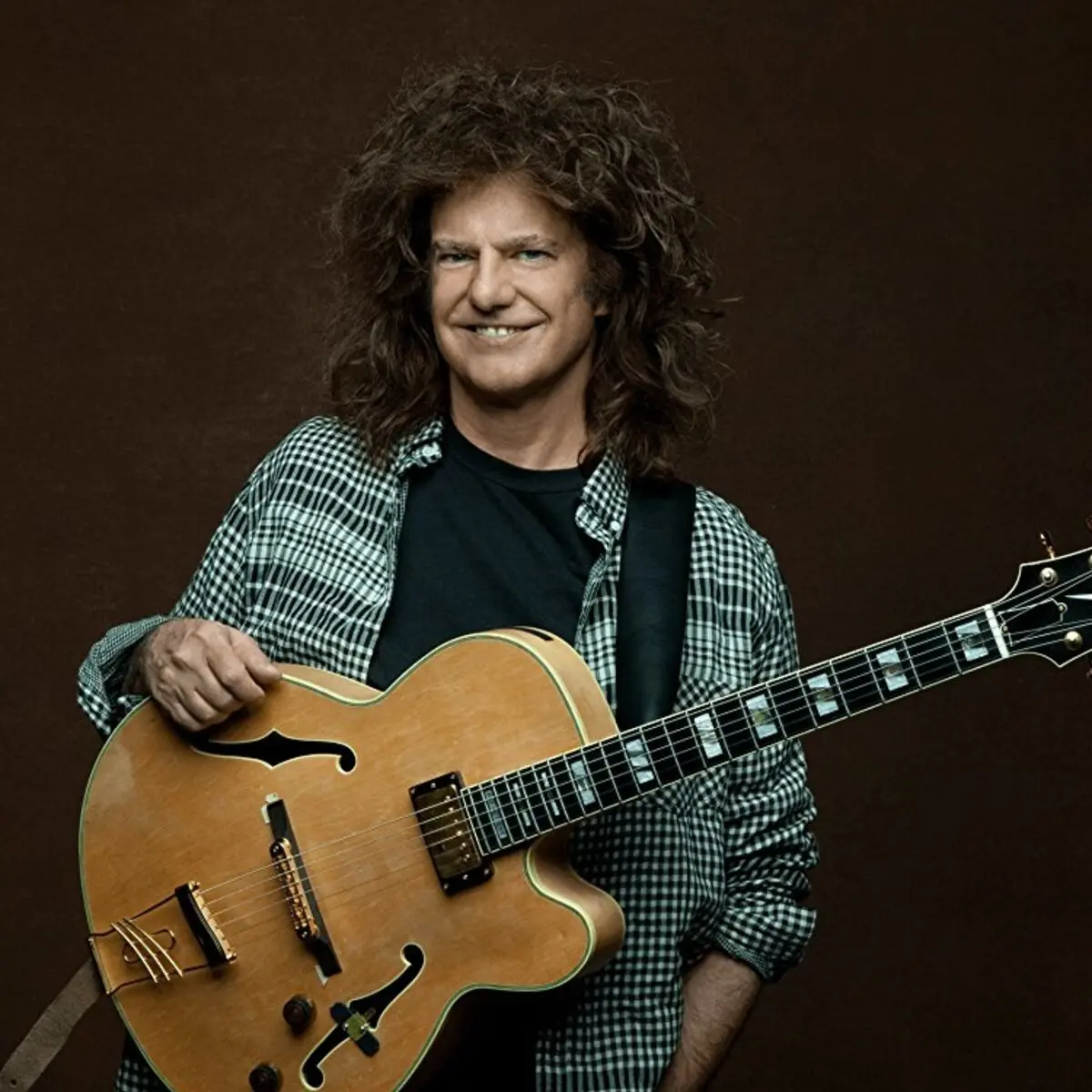

In the early 1990s, the lineup was mostly elder jazz statesmen but a number of blues and R&B artists appeared including Lou Rawls, John Lee Hooker and John Hammond. The variety expanded during the decade with artists such as Al DiMeola, Stanley Clarke, Tower of Power, Jean Luc Ponty, Earl Klugh, Larry Carlton, Lee Ritenour, Bruce Hornsby, Pat Metheny, Ahmad Jamal, The Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Al Jarreau, The Manhattan Transfer, Diana Krall, Béla Fleck, The J.B. Horns and Dr. John.

2000S, WEIN’S DEATH, CURRENT ORGANIZATION

Throughout the 2000s, the festival’s lineup has continued to be a hybrid of upcoming and established artists, essentially a who’s who of what was and what will be in modern jazz. In 2011, Wein returned the festival to its former non-profit status by establishing the Newport Festivals Foundation, which paved the way for new funding and has kept the event financially stable.

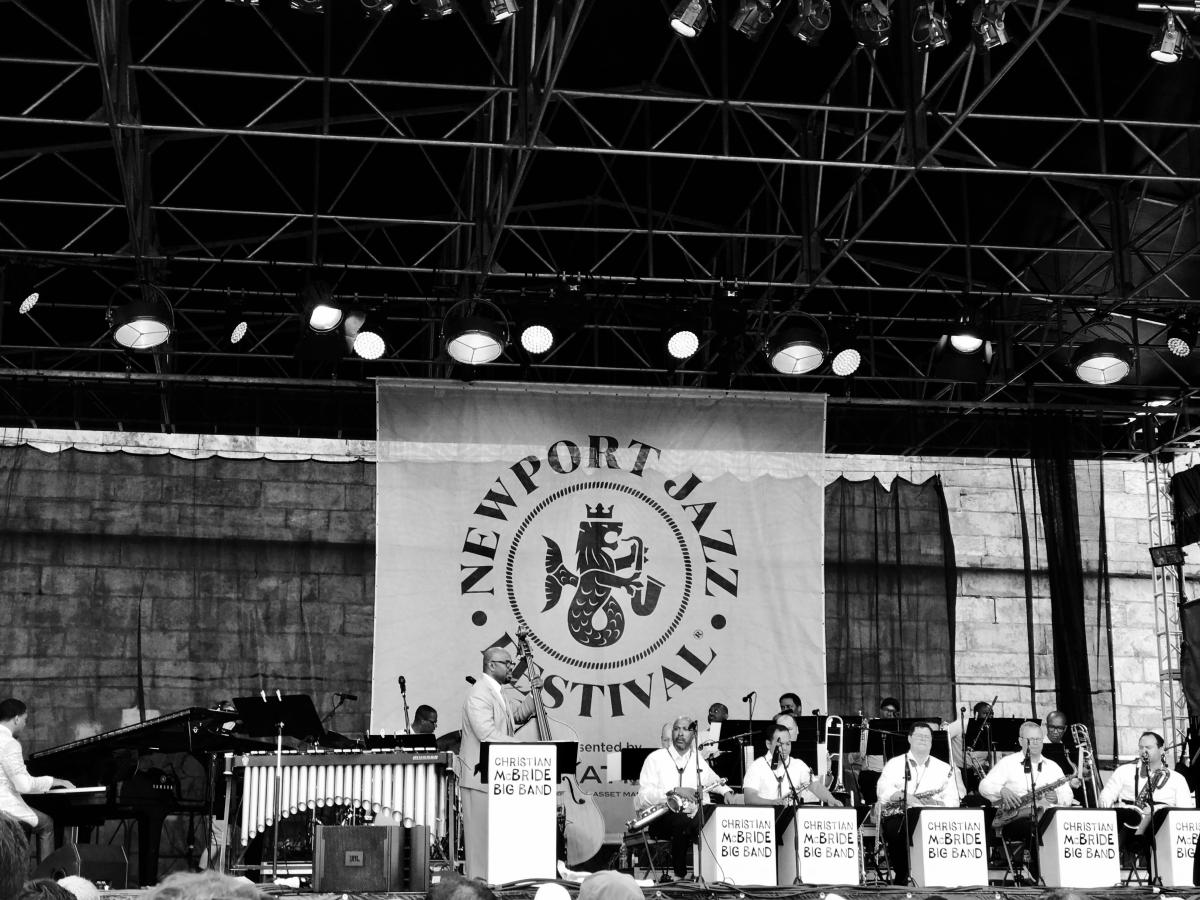

Following the 60th anniversary event in 2014, 89-year-old Wein decided on a plan for future festivals should he be incapacitated or pass away: Jay Sweet, former editor of Paste magazine, would be the executive producer; longtime Festival Productions presenter Danny Melnick would be the producer; and bassist-composer-arranger Christian McBride would handle bookings. When Wein died on September 13, 2021, that organizational structure came into effect.

But McBride says that Wein’s never far away. “Even with George gone, his spirit is very much alive with all musicians who knew him and all the fans who’ve been coming to the festival for many years,” he told PostGenre’s Shepherd in 2022. “I have a feeling that his presence will be felt at Newport for a very long time.”

(by D.S. Monahan)