Music Inn

For almost 30 years, and most profoundly in its first 10, Music Inn was a dynamic microcosm of American popular music and culture, a rare panoramic showcase of aesthetic and acoustical adaptations, creative cross-pollination and the country’s sweeping societal shifts. And that’s precisely what its founders intended.

From its opening in 1950 in the bucolic splendor of Lenox, Massachusetts, near classical-music mecca Tanglewood, they wanted Music Inn to be more than just a music venue: a place where music could be played, enjoyed, dissected, debated, and discussed; where the connection between artist and audience was symbiotic; where musicologists taught the roots of multiple genres; and where America’s post-WWII cultural transformations could be played out on and off stage. Throughout its years as a jazz nexus in the 1950s, a folk-blues hub in the 1960s and a rock-n-roll nirvana in the 1970s, Music Inn’s appeal was beyond music alone.

Opening, Ownership

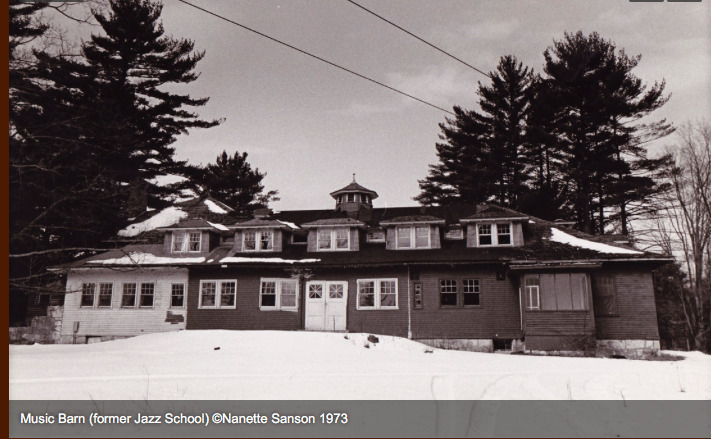

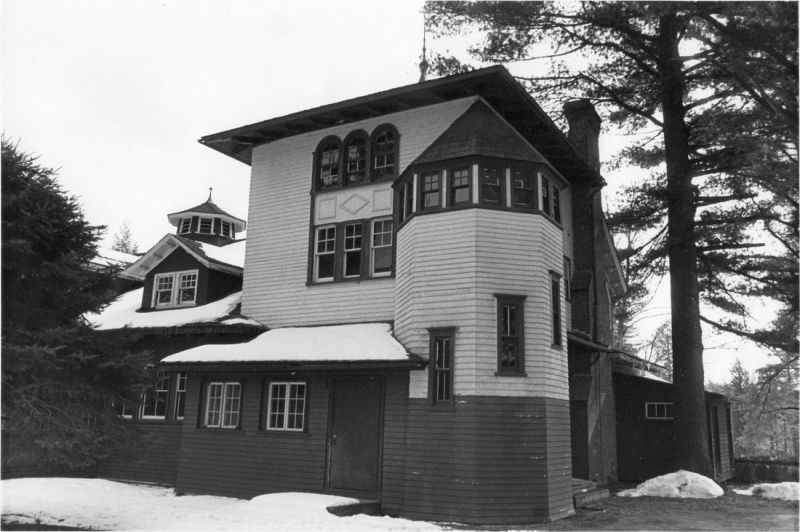

Open from 1950 to 1979, the venue’s history begins in 1947, the year after heiress Gloria de Heredia died and the Boston Symphony Orchestra bought 22 acres of her estate and Wheatleigh, her mansion, to be a dorm for Tanglewood students. In early 1950, New Yorkers Stephanie and Philip Barber purchased the remainder of the property – around 125 acres with a barn, stables, carriage house, potting shed, greenhouse and ice house – intending to create a cultural oasis to attract the big-city atmosphere they enjoyed. The couple, who were friends of folk singer Alan Lomax and writer-activist Langston Hughes, converted the barn into a 65-guest inn that doubled as a summertime bohemian boutique with live music (by African-American artists in particular) and music education.

It was a radical concept in the rather parochial region, the Barbers recognized at the time, but they were strongly determined to import multiculturalism to their adoptive home. “Black people were not popular in New England,” Stephanie said in 1998. “People in the village didn’t approve of what we were doing. But, in good New England fashion, they believed we had the right to do it.”

First Concerts, Folk and Jazz Roundtables, Notable 1950s appearances

Music Inn held its first concerts on July 2, 1950, when Alan Lomax, Woody Guthrie, Rev. Gary Davis and Pete Seeger appeared, and jazz critic-historian Marshall Stearns, a Cambridge native, led “Folk and Jazz Roundtable” discussions. The environment was relaxed and extremely unique in that musicians, critics and scholars lived together at the inn, which DownBeat editor Nat Hentoff compared to “being on shipboard.” The next weeks featured calypso, African drumming and ragtime, each performance followed by lectures and discussions.

By the mid-1950s, jazz greats including Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Dave Brubeck, The Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) and free-improvisation trailblazer Jimmy Giuffre were playing at the venue. In 1954, the same year the two-day Newport Jazz Festival began, the Barbers held a three-week jazz celebration. In 1955, after opening the 750-capacity Music Barn, they expanded to a five-week season.

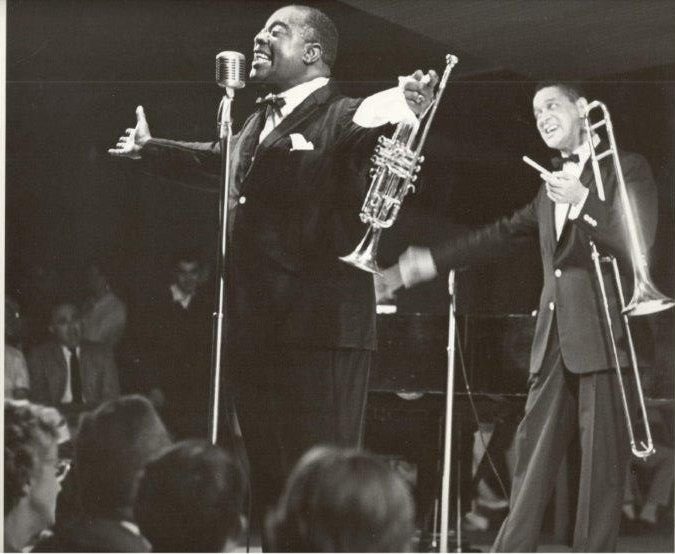

In 1956, Louis Armstrong played the Barn’s opening night to a standing-room-only 1,000-plus crowd and MJQ held a weeks-long residency , recording …at Music Inn, Vol. 1 for Atlantic Records. Also that year, Atlantic issued Historic Jazz Concert at Music Inn featuring bassist Oscar Pettiford, clarinetist Pee Wee Russell, drummer Connie Kay, pianist George Wein and others. In 1958, Sonny Rollins recorded the live album …at Music Inn and Atlantic released MJQ’s …at Music Inn, Vol. 2.

School Of Jazz, Expansion, First ownership change

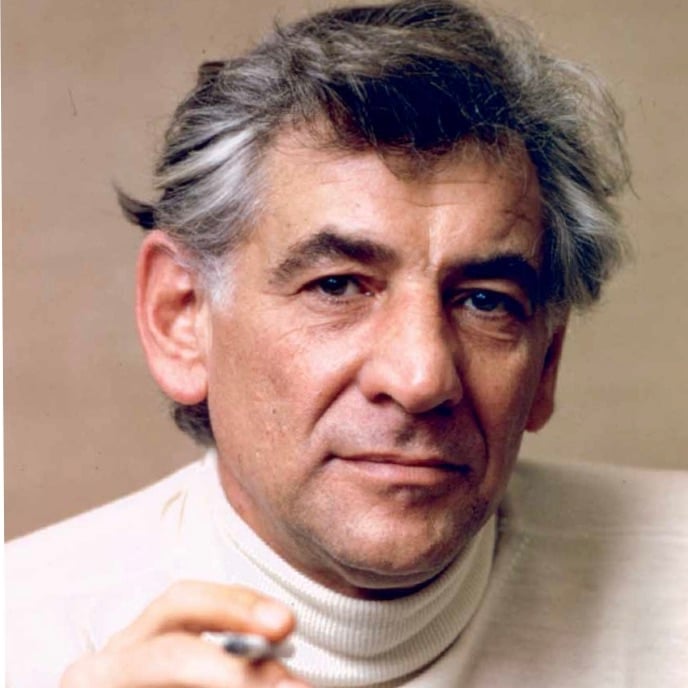

In 1957, the Barbers opened the School of Jazz under the directorship of MJQ founder John Lewis. Students including free-jazz maverick Ornette Colman studied under Lewis, Giuffre, Dizzy Gillespie, Lennie Tristano and Max Roach while jamming after hours with Tanglewood musicians, often with composer-conductor Leonard Bernstein observing. By 1958, Music Inn was considered a world-class jazz venue and educational facility and in 1959 the Barbers expanded further by renovating the potting shed for live music. With roughly 150 guests living on the premises and 27 events held that summer, their vision had become extraordinarily real.

In 1960, however, things changed dramatically when financial pressures forced the Barbers to sell everything but Wheatleigh to Don Soviero, a famously flamboyant entrepreneur who had modernized Pittsfield’s Bousquet ski area years before. The Barbers closed the School of Jazz in 1961 and Soviero ended all lectures and roundtables while expanding capacity to over 5,000, placing loudspeakers around the grounds and converting the potting shed into an upscale restaurant.

Notable 1960s appearances, Second ownership change

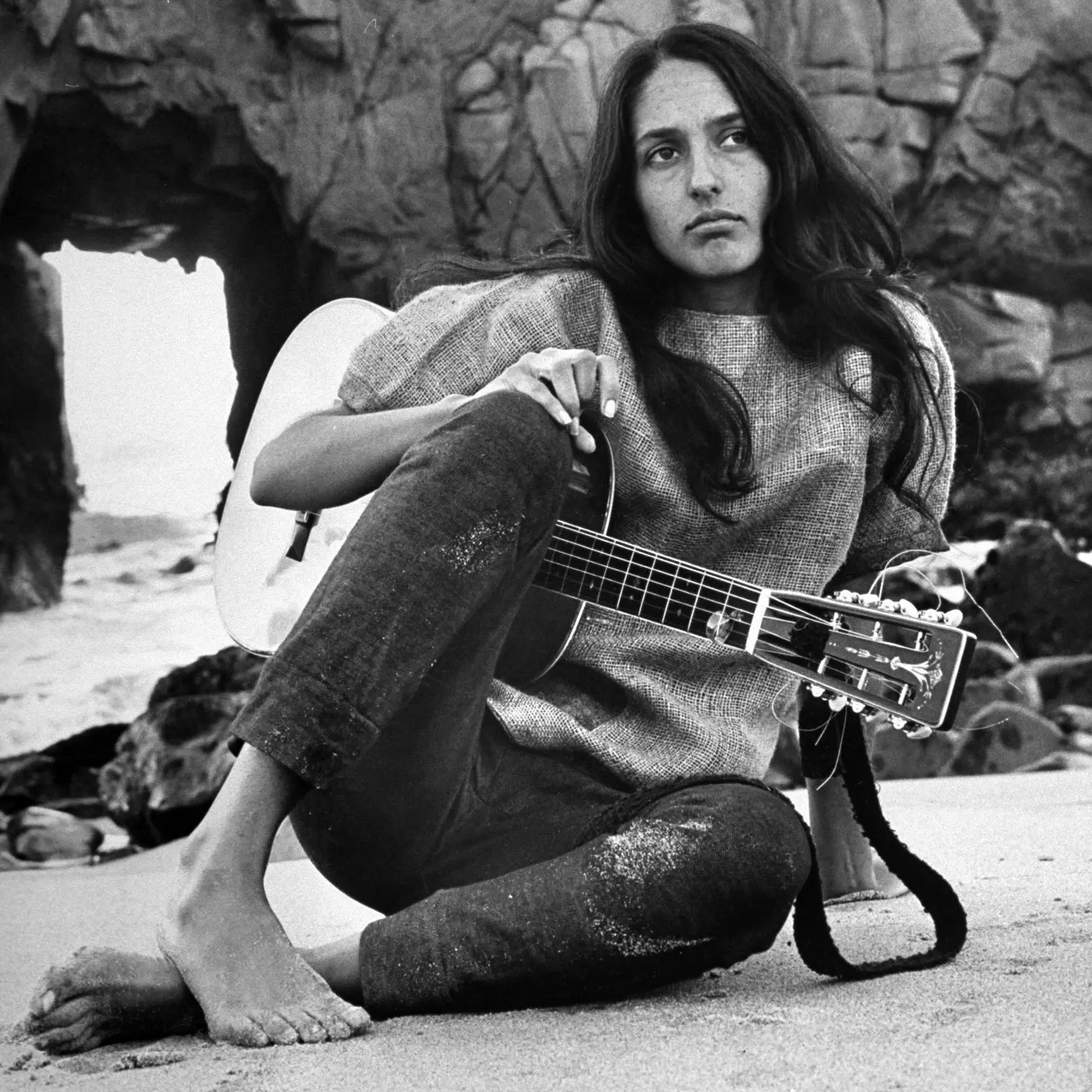

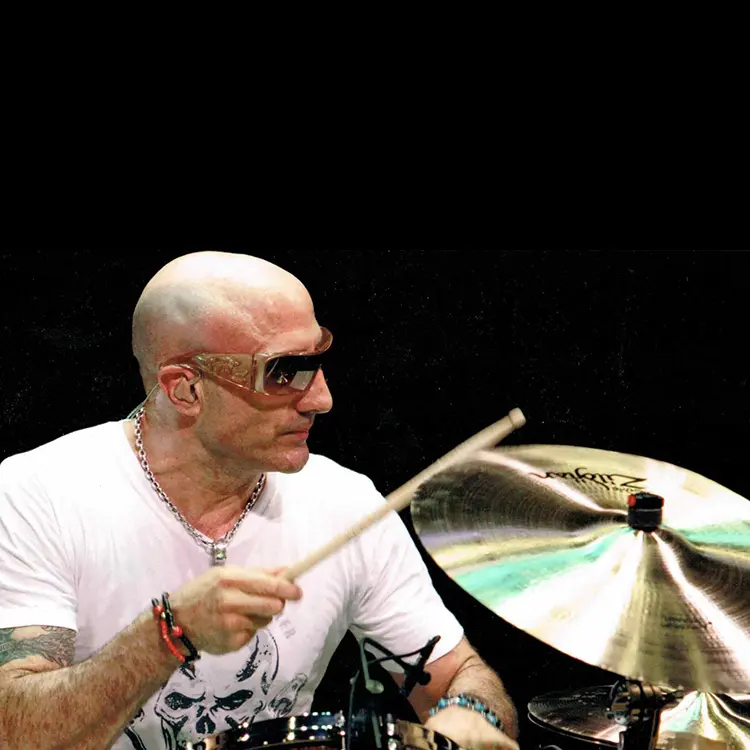

Until 1967, when Soviero went bankrupt and sold Music Inn, the repertoire still included jazz – Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughn, Ahmad Jamal and others debuted while Armstrong, Monk, Brubeck and MJQ returned – but shifted toward folk and blues. Among the acts that appeared were The Simon Sisters (featuring Carly Simon), Don McLean (years before recording his 1971 classic “American Pie”), Joan Baez, Odetta, Mahalia Jackson, Rev. Gary Davis, John Lee Hooker and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. The venue remained the go-to place for teens like renowned session/touring drummer Kenny Aronoff, a Stockbridge native who says he can “still smell the air and see the fireflies.”

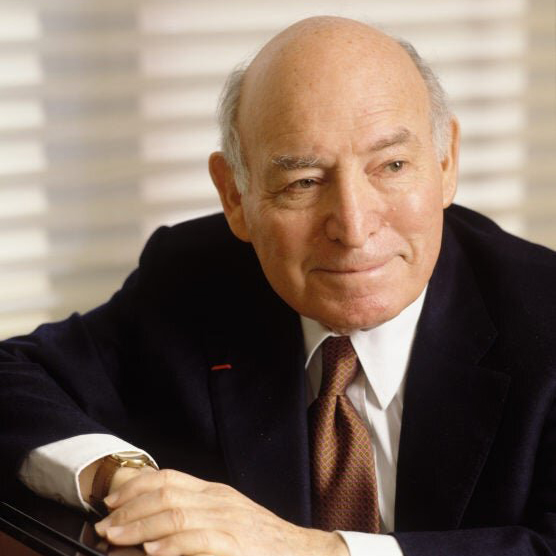

In 1969, architect-developer David Rothstein bought the entire property and, depending on who you ask, he either saved it or destroyed it. While there was a pervasive “Woodstock vibe,” according to most, Rothstein commercialized the grounds considerably – and controversially – by adding an art gallery, a movie theatre, a music shop, a head shop and two bars.

Notable 1970s appearances, Factors leading to closing

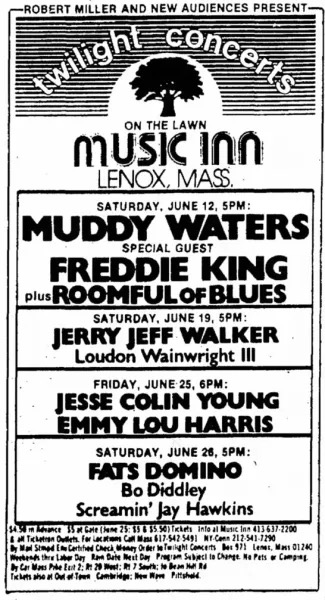

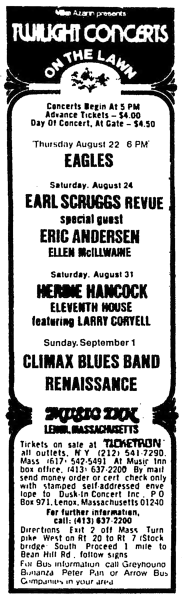

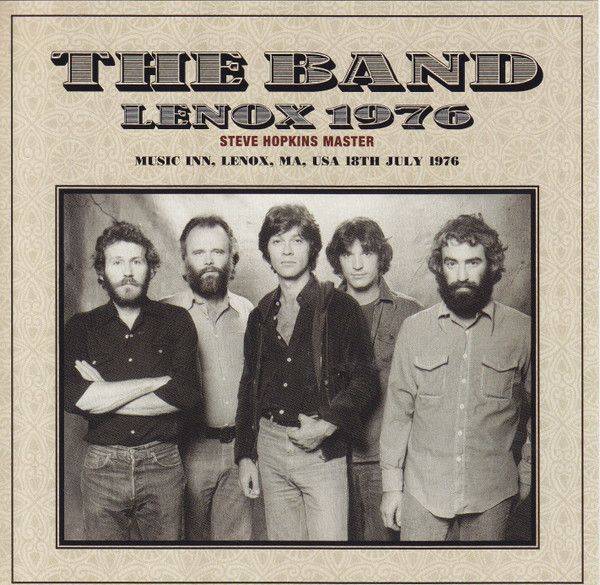

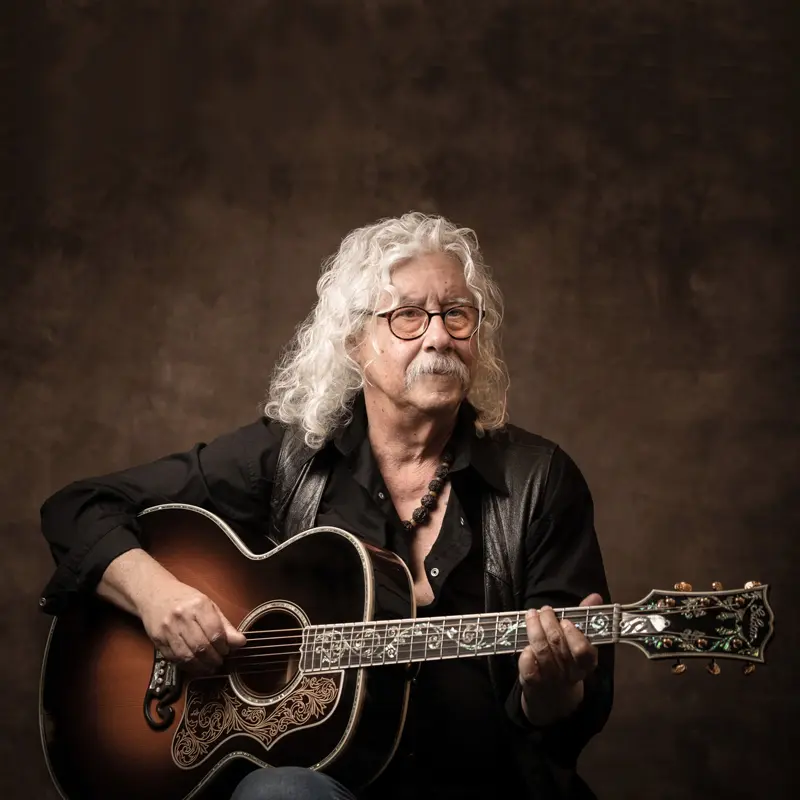

On July 4, 1970, Arlo Guthrie played the new decade’s first show at Music Inn – almost exactly 20 years after his father had done the same – and through the early 1970s folk was the mainstay with acts including Tom Rush, Janis Ian, The Byrds, America, Poco, Aztec Two-Step, Richie Havens, James Taylor and Taj Mahal. From 1974, however, the venue hosted primarily roots, rock and blues with shows by The Eagles, Bruce Springsteen, The Band, The Kinks, Hot Tuna, New Riders of the Purple Sage, Van Morrison, Bonnie Raitt, Lou Reed, Roomful of Blues and NRBQ. A few jazz-fusion acts appeared including Weather Report, the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Herbie Hancock.

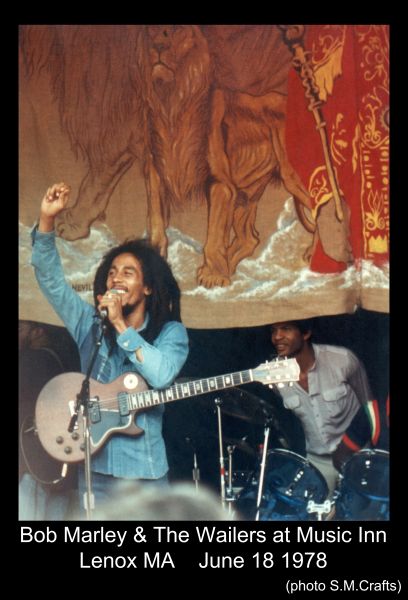

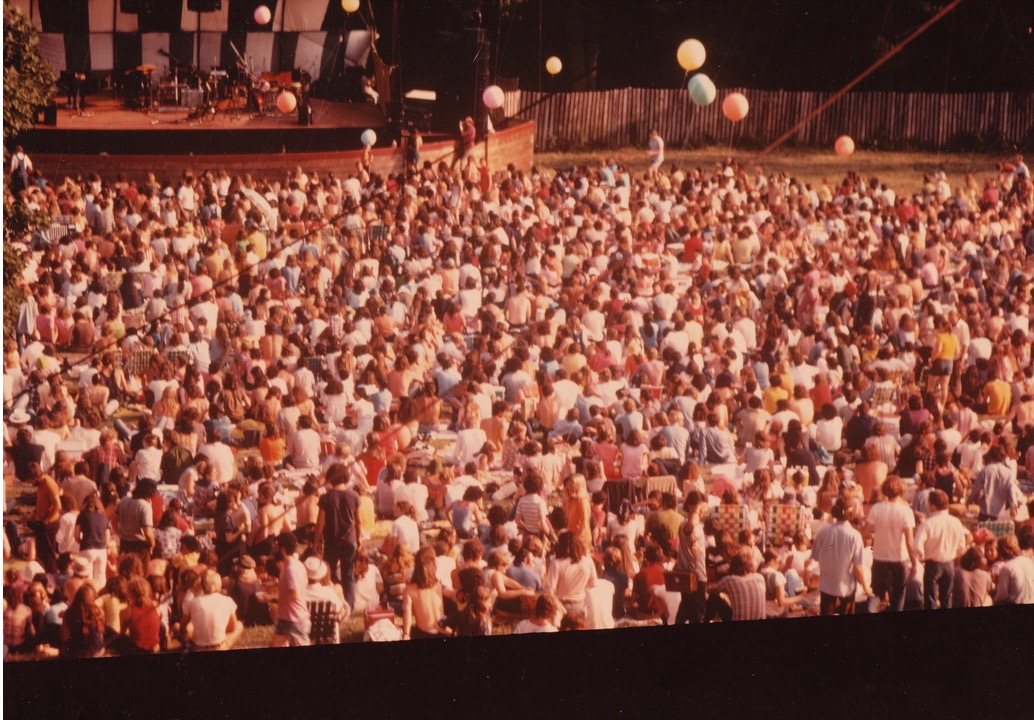

By 1978, when reggae icon Bob Marley and blues legend Muddy Waters played at the Inn, there were several factors that eventually lead to Rothstein closing it down, he said in 2017. First, increasingly boisterous crowds of up to 15,000 resulted in him spending countless hours meeting with selectmen and attorneys to fight legal actions by neighbors; second, the live-music business itself had changed, with artists demanding minimums and guarantees unlike before; and third, promoter Don Law was steering acts away from Music Inn in favor of Tanglewood, which had started hosting non-classical events, and other venues he controlled.

Final concerts, 2005 documentary, Legacy

The final straw came on August 26, 1979, when a rowdy crowd stormed the gates at an Allman Brothers concert, making it a near riot. Rothstein decided to close Music Inn but Arlo Guthrie secured permission for one last show, which he and Pete Seeger headlined in early September – poignantly, since Guthrie’s father and Seeger headlined Music Inn’s very first concert in 1950.

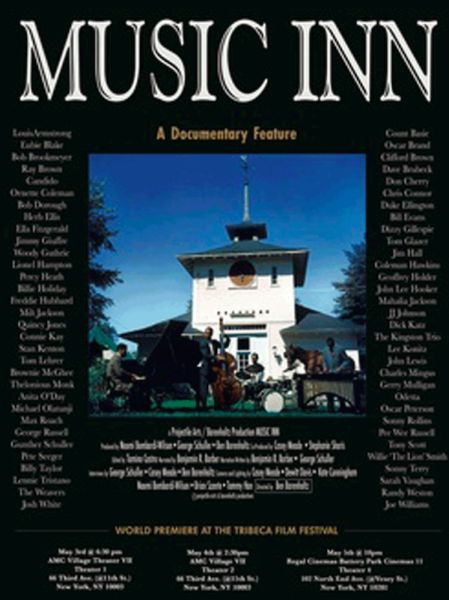

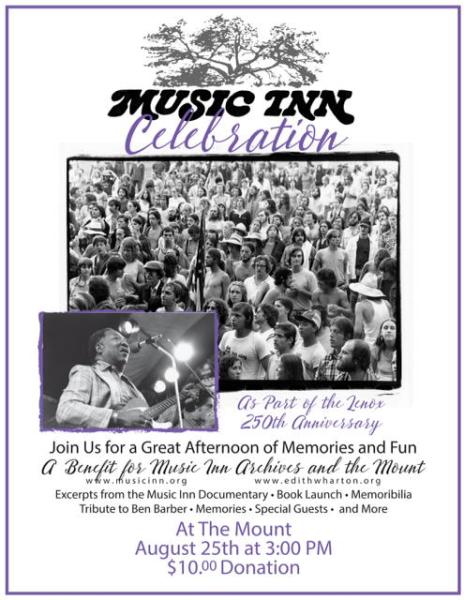

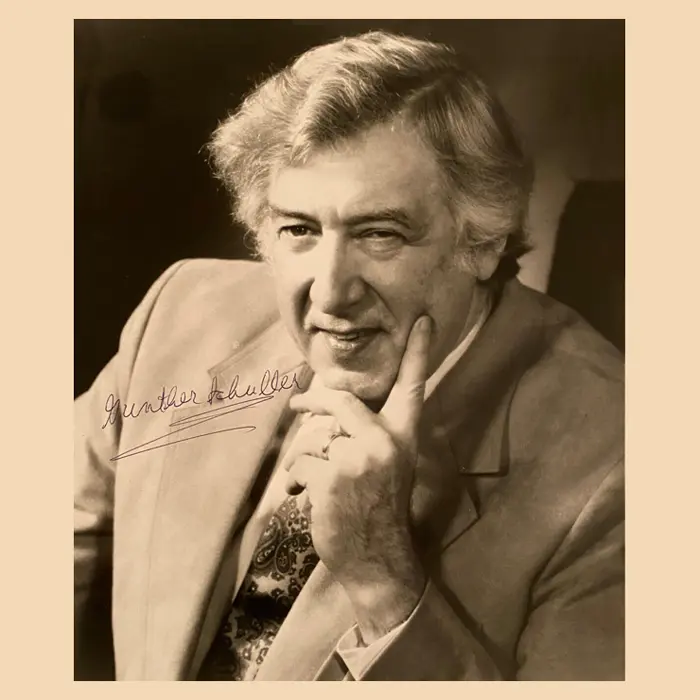

In 2005, Projectile Arts released a documentary about the venue’s 1950-1961 period, Music Inn, co-produced by George Schuller (Gunther Schuller’s son) and narrated by Benjamin Barber (founder Philip Barber’s son).

Asked in 1995 about Music Inn’s reputation and legacy, Stockbridge native Nancy Fitzpatrick, a regular patron who owned the venerable Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge with her husband from 1968-2013 – and whose daughter and granddaughter run it to this day – said it was far less threatening than people thought. “Tanglewood was kind of the establishment; Music Inn was the renegade concert venue,” she recalled. “Everybody’s parents worried about what went on there. They would have been disappointed to find out how innocent it all was.”

(by D.S. Monahan)