Music Hall / Wang Center / Boch Center

A number of significant New England music venues have had several different names, among them Boston Music Hall (which became the Orpheum Theatre, then the Aquarius Theatre, then the Orpheum Theatre again), Boston Garden (which became the Fleet Center, then TD Garden), Club Mount Auburn 47 (which became Club 47, then Club Passim) and the Majestic Theatre (which became the Saxon Theatre, then Cutler Majestic Theatre).

But the one that takes the prize as the most multi-monikered of all the region’s major music meccas has had more marquees than any of the above – six, to be exact. It opened as the Metropolitan Theatre then became Music Hall, the Metropolitan Center, Wang Center for the Performing Arts, Citi Performing Arts Center and, currently, The Boch Center Wang Theatre. And call it whatever you like because – like each of the other venues noted above – while its signage hasn’t been consistent through its history, what matters most always has: the multigenred mix and unquestionable quality of the music within its walls.

Opening, Cost, Capacity, Design

The venue opened on October 25, 1925, as Metropolitan Theatre (“the Met” to locals) at 252-272 Tremont Street. The first owner was the Publix Theatres Corporation (a chain with venues across New England and the greater US) and it was built at a cost of $8.5 million (about $138 million in 2022). The Met had a capacity of 4,400, the biggest theatre in Boston at the time and a quintessential example of the grand “movie palaces” that were wildly popular during the Roaring Twenties.

The building was designed by esteemed architect Clarence Blackall who, like Bullfinch, trained at L’ École Nationale Supérieure Des Beaux-Arts in Paris and, unlike Bullfinch (whose sole Boston project was Federal Street Theatre), designed 12 additional buildings in the city including three other theatres (Gordon’s Olympia, the Colonial and the Wilbur) and the Copley Plaza Hotel. It was built on the grand architectural scale of the city’s first major theatrical venue, the Federal Street Theatre (1793-1852, also called the Boston Theatre), which was designed by Charles Bullfinch (a Bostonian who also designed the US Capitol building’s rotunda and dome).

The 14-story Renaissance Revival-style structure boasted one of the most ornate façades in New England – fluted Ionic columns, recessed spandrels, Corinthian pilasters, decorative dentil cornice and granite palmettes engraved with theatre masks – and was called a “palazzo skyscraper” in the press (“palazzo” meaning a “large, imposing building” in Italian). The Met’s owners promoted it as “a public castle with 1,001 wonders.” The Louis XIV-style interior, modeled on the Palais Garnier opera house in Paris, featured French-marble doorways, jasper-toned pillars, gold-plated chandeliers, burnished-bronze detailing and murals by Edmund Philo Kellogg adorned with $10,000 worth of gems (about $148,000 in 2022).

Early events, Sophisticated vibe

Opening-weekend events featured music, theatre and film including an orchestra performing Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture,” a stage presentation of “The Melting Pot” – a 1908 play about a Jewish family emigrating to the US from Russia that some New Englanders compared to their own emigration from the UK – and the new Paramount Pictures silent romantic comedy The King of Main Street. Met manager Ralph E. Crabill said that each show sold out.

The Met’s entertainment offerings became as extravagant as the theatre itself, with showings of the latest films and performances by its resident ballet corps, 100-voice chorus, 55-piece orchestra and headliners including Rudy Vallée, Al Jolson, Burns and Allen, Jack Benny and Bob Hope, with admission ranging from 35-75 cents (about $5.50-$12.00 in 2022).

Like Symphony Hall and Cocoanut Grove, the venue had a sophisticated vibe, with 40 meticulously mannered, uniform-attired ushers guiding ticket holders to their seats. Other patrons sat within the sybaritic splendor of the lounge listening to the house chamber orchestra or dining in the theatre’s art-deco restaurant, opened in 1932.

Becoming “Music Hall,” First rock concert

In 1962, Sack Theatres bought the Met and renamed it Music Hall., which became the home of the Boston Ballet and staged performances by the Bolshoi Ballet and the Kirov Ballet. It also hosted New York’s Metropolitan Opera and the Stuttgart Opera while continuing to stage other musical productions and show first-run films. In August 1963, The Beach Boys became the first group classified as “rock ‘n’ roll” to perform at Music Hall – a harbinger of the venue’s near future – but rock acts didn’t start appearing regularly until five years later.

Commercial threats, Saved by rock ‘n’ roll

In the mid-‘60s, Sack Theatres faced two dire threats to its core businesses: first, showing films had become less lucrative than before, since the increasing ubiquity of suburban movie theatres led major film distributors to stop offering exclusivity agreements; second, due to Music Hall’s comparatively small stage and its significantly outdated production facilities, many larger touring companies began opting for larger, more modernized venues.

That rapidly changing commercial tide forced Sack Theatres to steer Music Hall in a significantly different direction. And the rudder they chose to do so was a musical genre still in its relative infancy at the time – what kids in the ‘50s had called “rock ‘n’ roll” but what those in the ‘60s called simply “rock” – which successfully steered the perilously low-profit venue into smoother financial seas until 1980, like a Titanic that avoided the iceberg.

Early concerts, Most frequent acts

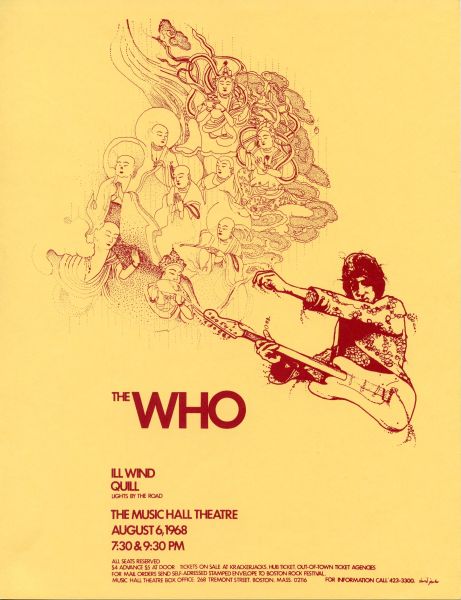

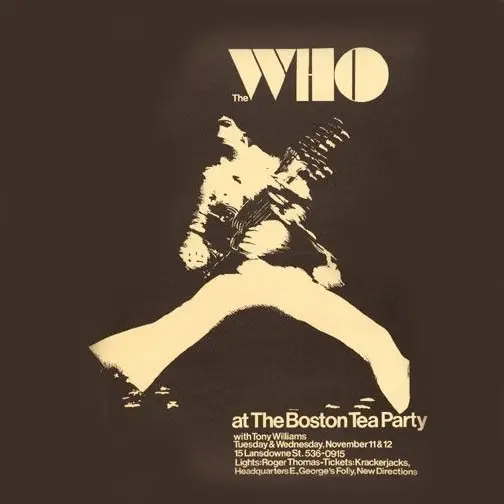

In August 1968, The Who appeared at Music Hall, the first of dozens of rock bands that would do so over the next dozen years. The next were The Beacon Street Union, The Grass Roots and The Beach Boys, who played on a triple bill in November, followed in 1969 by three more rock acts – Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane and Donovan – and shows by Johnny Cash, José Feliciano, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem.

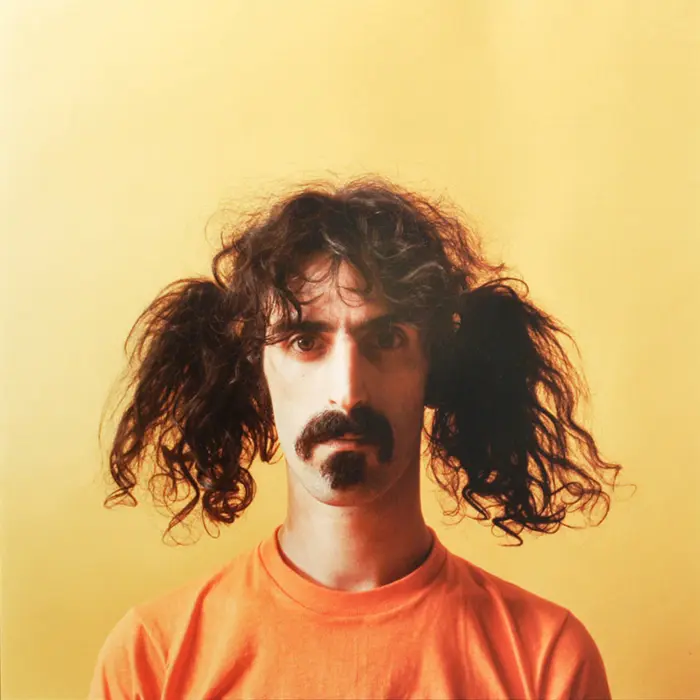

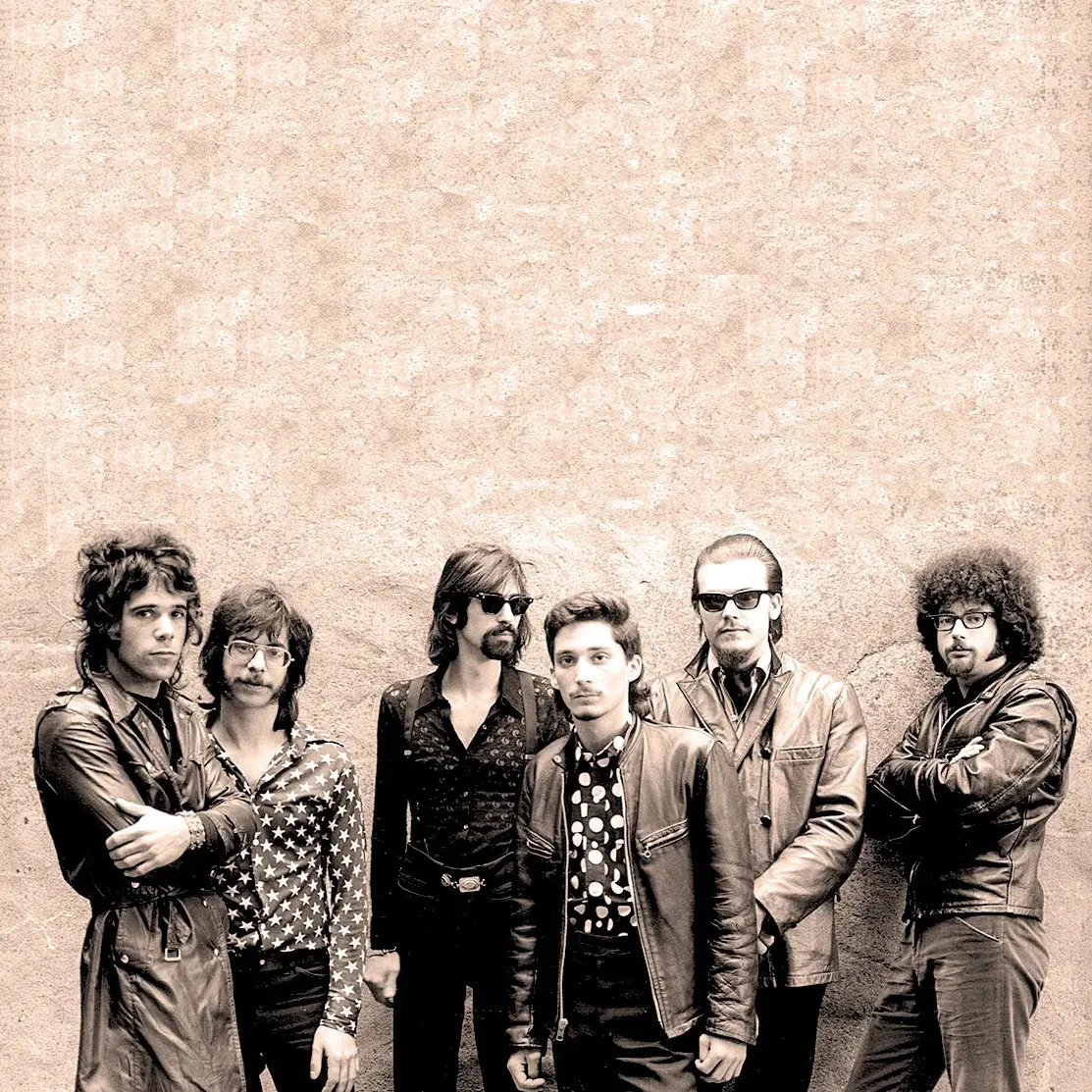

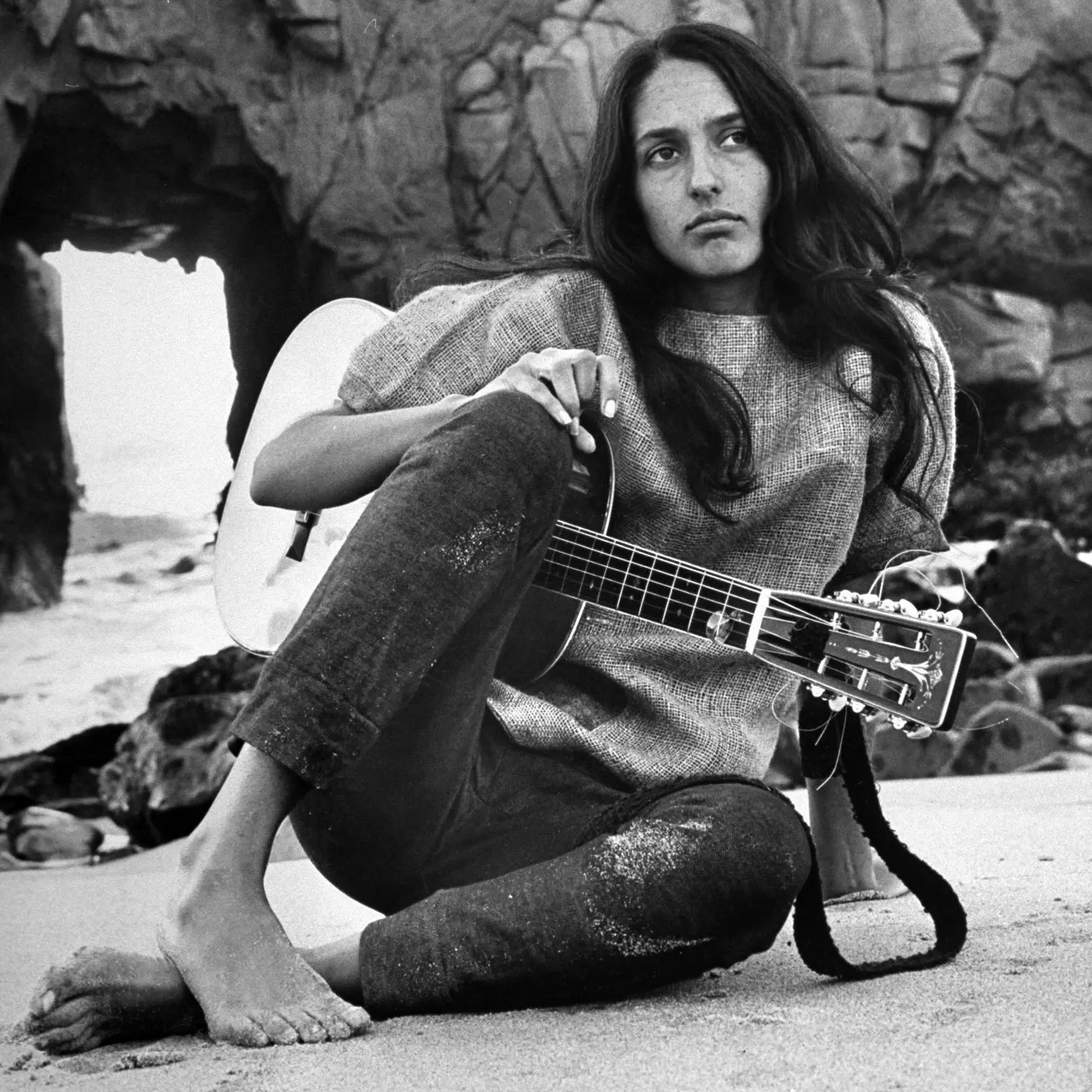

From 1970 until Frank Zappa played the final rock concert at Music Hall in May 1980, the Grateful Dead appeared the most – 15 times – followed by Zappa (11), Bruce Springsteen (10), Cat Stevens (7), The Beach Boys, The Kinks, Aerosmith and The Cars (6 each). Other New England-rooted acts that hit the Music Hall stage were Van Morrison, The J. Geils Band, James Taylor, Joan Baez, Boston, Bonnie Raitt, Sha Na Na and Donna Summer.

Other notable appearances

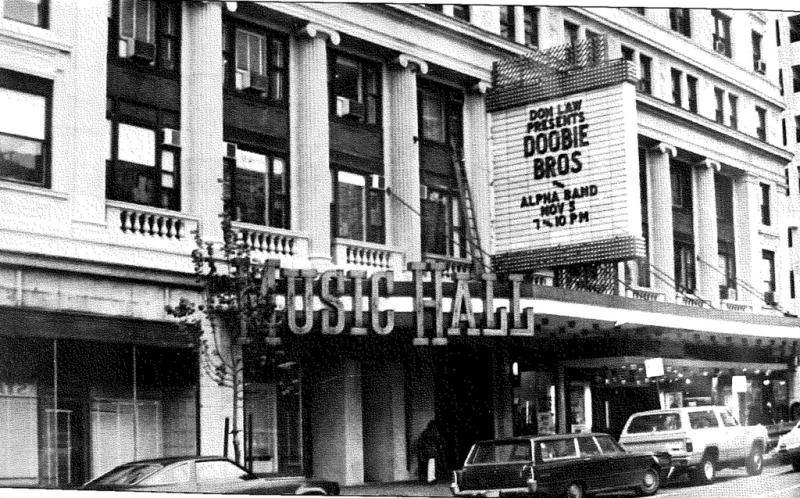

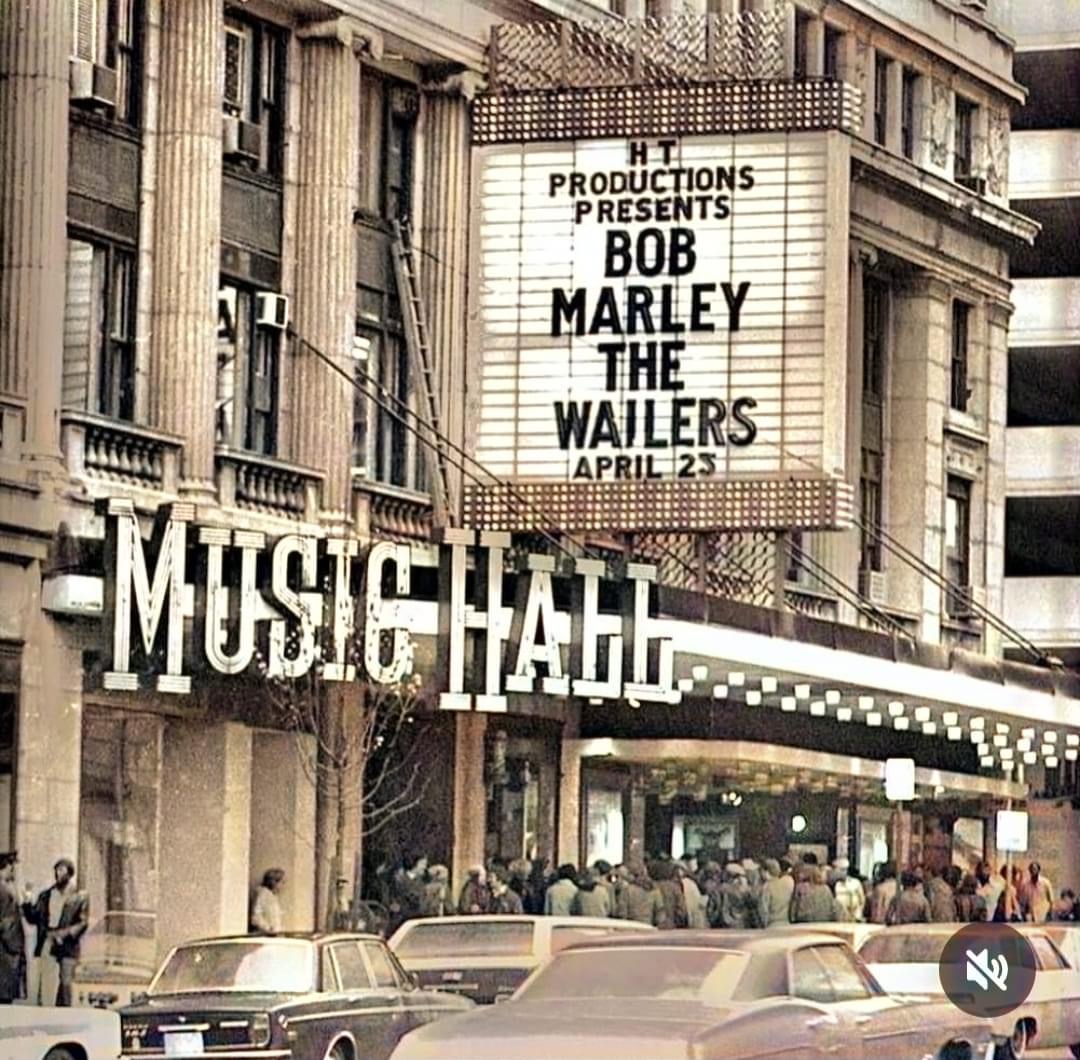

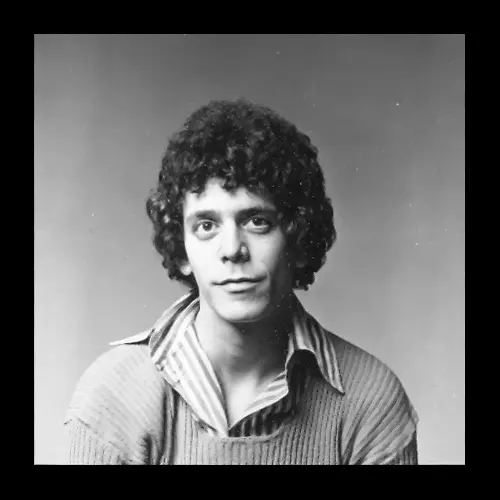

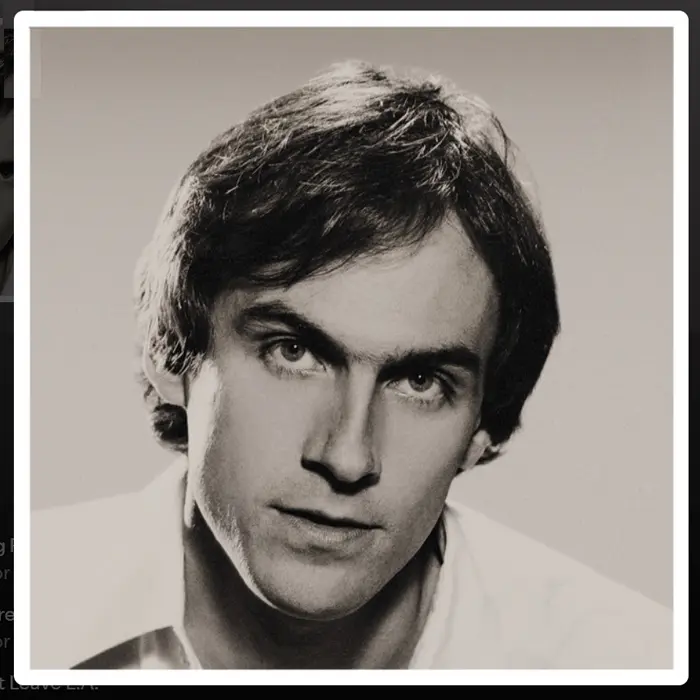

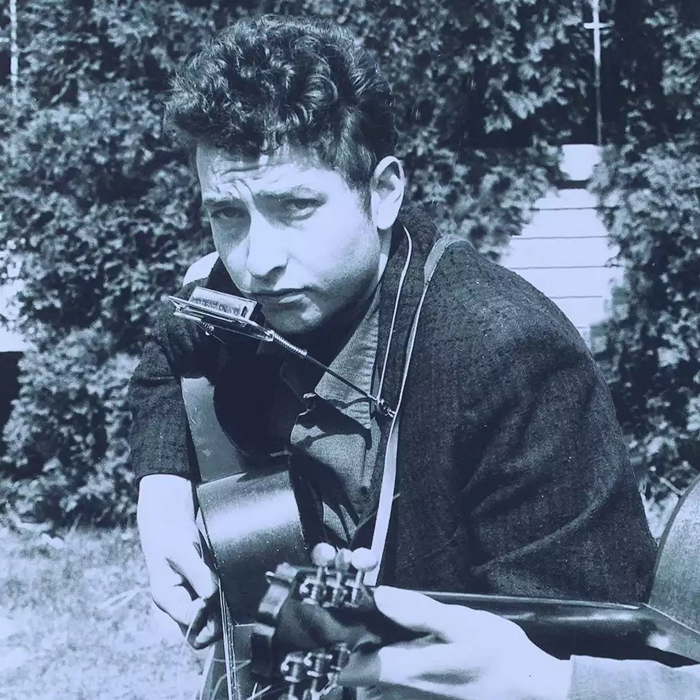

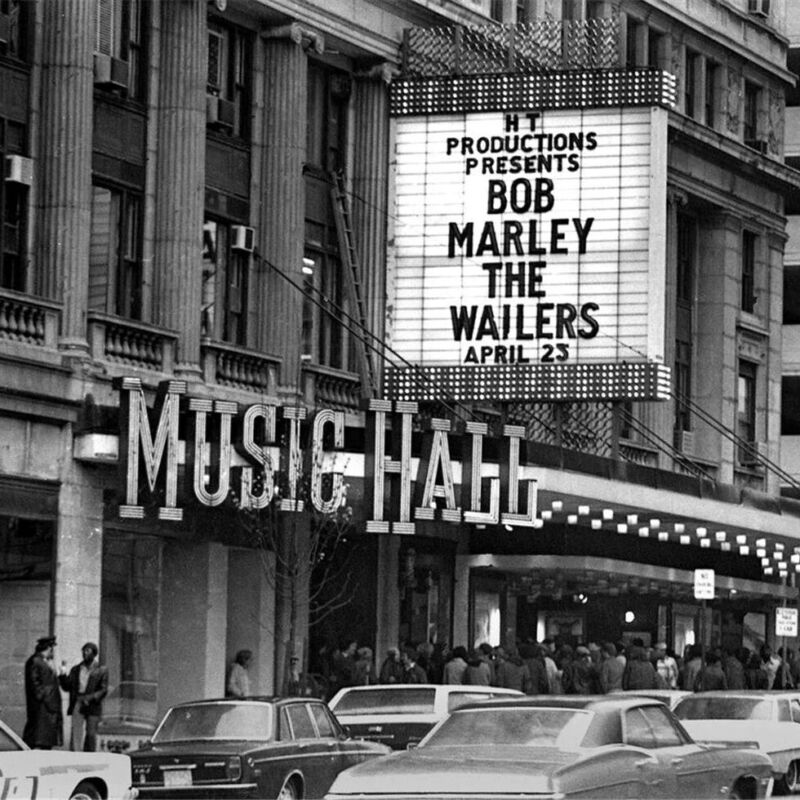

When it comes to other artists who appeared, anyone even vaguely familiar with ‘60s/’70s-era American radio will recognize most – and probably all – of the names. Among them are Muddy Waters, Frank Sinatra, Chuck Berry, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Queen, Elton John, Lou Reed, The Doors, David Bowie, Fleetwood Mac, The Band, The Doobie Brothers, Joni Mitchell, Alice Cooper, Paul Simon, Blood, Sweat & Tears, The Allman Brothers, Jeff Beck, Heart, Pink Floyd, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Steve Miller Band, Bob Seger, Santana, Neil Diamond, Jackson Browne, The Eagles, Cheap Trick, Sly & the Family Stone, Hall & Oates, The Moody Blues, Black Sabbath, ABBA, Lynyrd Skynyrd, ZZ Top, The Pointer Sisters, Deep Purple, Jimmy Buffet, Procol Harum, Patti LaBelle, Yes, Jethro Tull, Barry Manilow, Foghat, Johnny Winter, Blue Öyster Cult, Genesis, Supertramp, Earth, Wind & Fire, Bad Company and Bob Marley & The Wailers (whose June 1978 Music Hall show Island Records released in 2015 as Easy Skanking in Boston 1978).

Metropolitan Center, Wang Center, Joe Spaulding

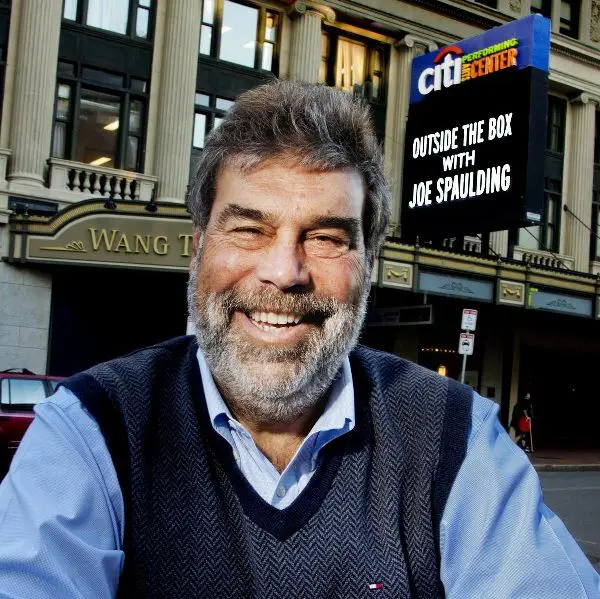

In 1980, with substantial repairs necessary but coffers too empty to afford them, Music Hall became the Metropolitan Center, a nonprofit, and modest restoration of the stage and backstage were enough to attract some major Broadway shows. In 1983, the theatre received an extraordinary donation from Wang Laboratories co-founder Dr. An Wang and his wife Lorraine and was renamed Wang Center for the Performing Arts, with renowned entertainment-business entrepreneur Joe Spaulding becoming its CEO in 1986, a position he holds to this day.

Restoration, Citi Perfoming Arts Center, The Boch Center

Between 1989 and 1992, Spaulding and his team raised $9.8 million, then commissioned Boston-based Finegold Alexander Architects to restore the theatre to its full ‘20s-era glory, with a capacity of 3,500 and one of the five largest stages in the US. In 1990, the Boston Landmarks Commission designated Wang Center a Boston Landmark as part of the Piano Row district; it’s also on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2006, as part of a 10-year partnership with Citigroup, Wang Center became Citi Performing Arts Center and in 2016 it became The Boch Center, which includes The Wang Theatre and The Shubert Theatre.

Current program, Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame

Along with concerts by a broad array of musical acts, The Boch Center presents a dazzling array of world-class Broadway, family, comedy, dance and educational programs. Since 2019, it has housed the Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame, exhibiting hundreds of displays, artifacts and pieces of memorabilia in addition to hosting concerts, lectures and other events related to each of those three genres.

According to its website, Wang Theatre at Boch Center aims to provide “high-quality, diverse and culturally relevant arts and entertainment,” and for untold thousands of music lovers across New England that will come as no surprise. After all, that’s precisely what the venue has been doing for almost 100 years – whatever its marquee happened to be.

(by D.S. Monahan)