Mother’s Lunch

In the dark days of America’s past, it was very difficult for an itinerant Black musician on the road to find a place to stay after a gig was over since most hotels were open only to whites. Boston was no exception; even a bandleader as polished as Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, whose orchestra made regular summer tours of New England beginning in the mid-1920s, had to stay at a private residence in the South End when he played in the area.

Over time, Ellington became familiar to the daughter of one woman who would rent a room to him when he passed through town. When the young girl was allowed to attend a performance by the Ellington orchestra for the first time, she turned to her mother when the band started to play and said, “I didn’t know Uncle Eddie played the piano!”

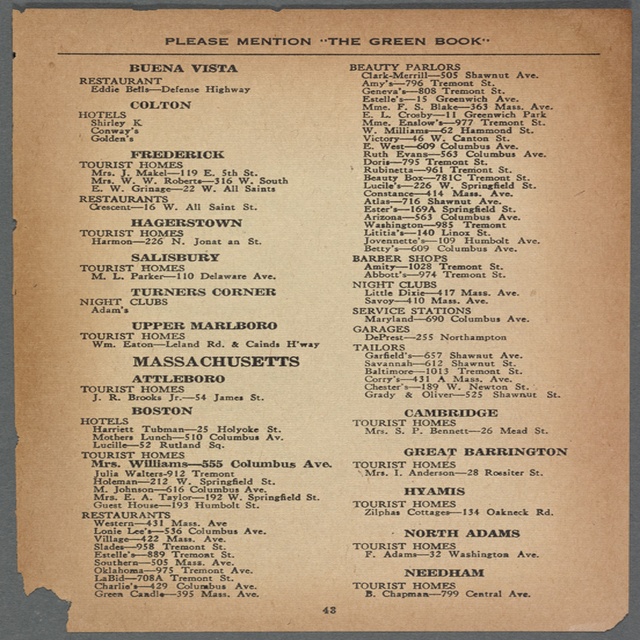

As a result of this color line in hotel accommodations, the jazz fraternity created a demand that was filled by a word-of-mouth network that could be tapped by making inquiries among the Black community. For musicians traveling through Boston, they were often directed to two places: “Chicken Lane,” a “real swinging place . . . out toward Roxbury,” according to Count Basie, or Mother’s Lunch, which operated out of various locations closer to the center of town, including one on Tremont Street and another at 510 Columbus Avenue.

Whilhelmina Garnes, Notable guests, Preferred over hotels

The “Mother” in question was Wilhelmina Garnes who, The Boston Chronicle claimed, “was known to the theatrical and music trade from coast to coast.” Among the jazz luminaries who stayed at Mother’s were Basie, Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Andy Kirk and J.C. Higginbotham, a trombonist who lived in Boston for five years. Mother’s Lunch had rooms to let upstairs, and Basie’s band would commandeer them all when they played Boston. Downstairs was a restaurant that expanded to a sidewalk café during the summer and a rehearsal space. On the second floor was The Tangerine Room, a nightclub that operated into the early morning hours.

Boston hotels began to admit Blacks in the mid-to-late 1930s; Count Basie recalled that both he and Billie Holiday were able to book rooms at the Ritz-Carlton in 1937, saying that was “a very big deal back in those days.” Once Black musicians were able to gain admittance to high-class hostelries, though, they sometimes found that the grass on the other side of the fence had only appeared to be greener. “I spent most of my time out at Mother’s Lunch,” Basie said after he’d been allowed to register at the Ritz-Carlton. “That was where the band stayed,” he said, noting that he found the atmosphere there to be more congenial than at the hotel.

Andy Kirk, the Kansas City bandleader, had the same reaction after Mother’s Lunch was taken over by a woman named Ann Johnson. “There was a regular network of homes and small black hotels across the country, north and south,” he said, then provided a sample conversation between two musicians before a Boston in 1939. “Where you stayin’?” asks the first. “Mom’s Lunch,” says the second. “Not the Waldorf. Homier.”

Jazz fan mecca, “Best Jazz in Boston,” Closing, Legacy

Naturally, the traffic of musicians in and out of such places made them quite a significant attraction for jazz fans. George Frazier, the acerbic critic who wrote the first column devoted to jazz in an American newspaper, The Boston Herald, noted that the first-floor rehearsal space at Mother’s Lunch provided the “best jazz in Boston” one week in 1942 when “Louis Armstrong rehearsed his band daily” there.

The end for Mother’s Lunch and similar informal lodging arrangements for jazz musicians around the country came when hotels began to integrate, which didn’t occur on a widespread basis until the 1950s. No one regrets the passing of segregated places of public accommodation, but something was certainly lost when places such as Mother’s Lunch were no longer around to serve as magnets for jazz talent. As Count Basie said about Chicken Lane in Roxbury, “A lot of fine beautiful people used to hang out in there.”

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).