Monoman + Oil Truck = Mission of Burma?

I spent my high school years in Darien, Connecticut, a leafy suburb of New York City, ravenously consuming music from all spheres – Soft Machine to Slade, Ornette to Iggy, Beefheart, Bowie and always, always, The Kinks. About the only person who could keep up with my own eclectic listening habits was Jeff Conolly, who was a year younger than I was and – though I’m loathe to admit it – possibly even more music-deranged than myself. He and I once threw a band together for a high-school talent show and played tunes as varied as Zappa’s jazz-fusion instrumental “Peaches en Regalia” and Otis Redding’s hit “Can’t Turn You Loose.”

I discovered New York’s underground music scene and would slip into Greenwich Village often to catch The New York Dolls at Max’s Kansas City, showing up the next morning in math class at Darien High School with smeared eye makeup. Around ’75, the glitter scene – heavily based on retro-activating primitive rock energies and outrageousness – was evolving into something entirely new, refreshingly strange and absolutely captivating. There were the clipped, austere sounds of a RISD trio, the hard, compact pop pellets from leather-clad cartoon toughs from Queens and the florid guitar ecstasies from a group calling themselves Television. You’d see the same 40 or 50 people at these shows in the legendary dive on the Bowery.

My life was changed. Those new sounds utterly upended my world. I’d moved on to college in Rochester but I’d regularly make the long pilgrimage to NYC to dose up on the enormous energies exploding out of a small corner in the city’s downtown district. It was the birth of a whole new world and I would messianically carry this message back to my puzzled classmates at school.

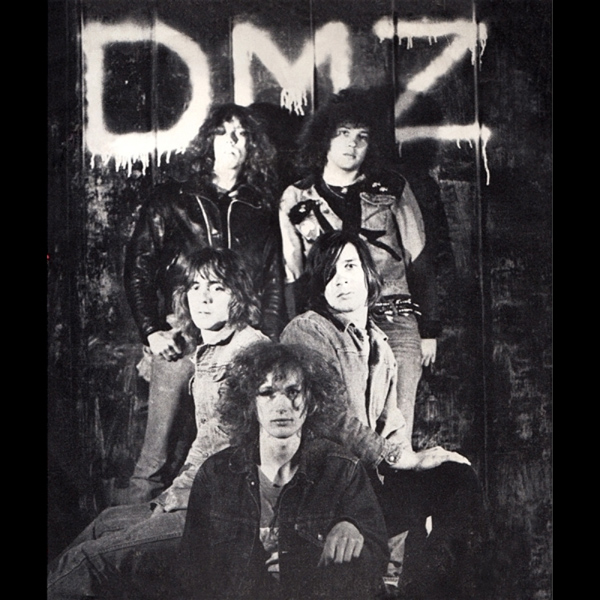

One person who totally got it was my old Darien friend, Jeff Conolly. He was going to Boston University and had started playing with a band in Kenmore Square at a place called The Rathskeller. The group was DMZ and he told me they played Iggy songs, Sonics songs and their own stuff. He also told me that demi-goddess Patti Smith had bestowed her bohemian blessing upon them by joining them on stage. Jeff was so excited, so transformed, that he’d adopted a new name: Monoman. I was intensely envious. He’d had taken the first big step while I was still standing on the outside looking in.

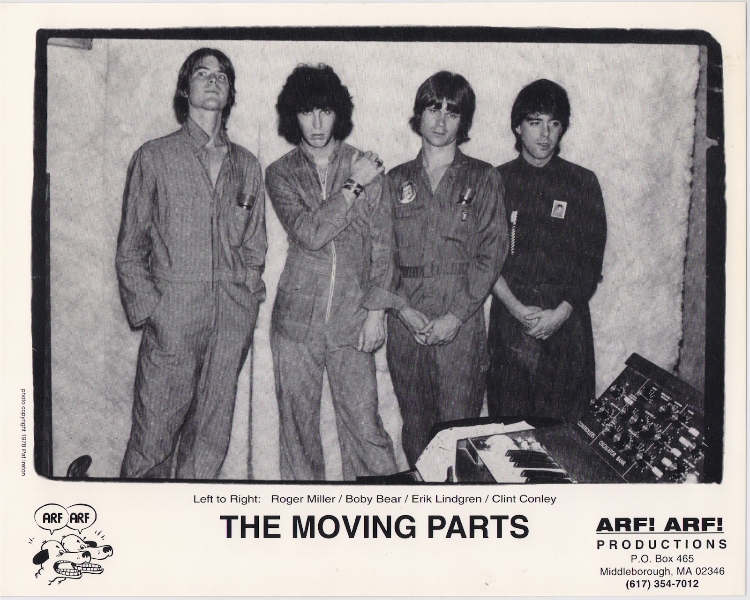

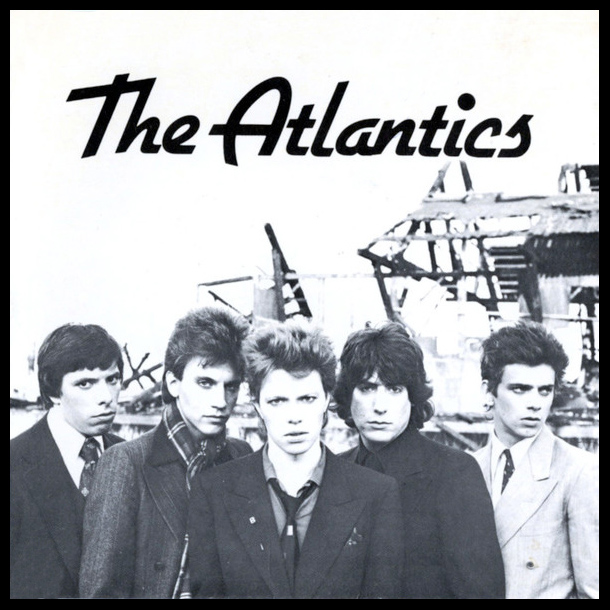

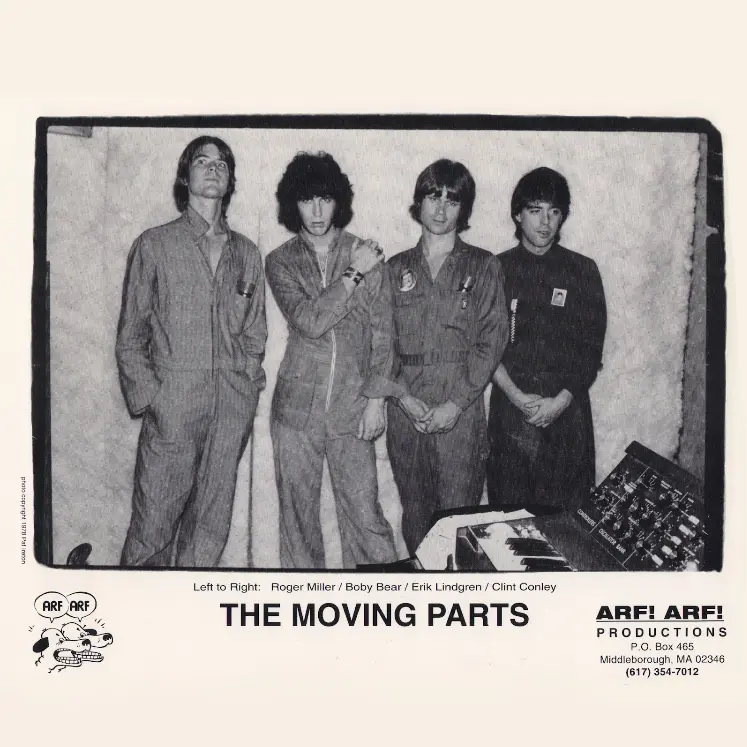

Given all this, I jumped at the chance when a friend of a friend was starting a band in Boston. Erik Lindgren, a quirky record collector friend of my journalist friend Chip Lamey, had a masters in composition counterbalanced by an appreciation for raw, elemental rock. Perfect. He’d recruited Boby Bear, formerly of The Atlantics and prince of a man, on drums. Perfecter. Lindgren’s parents had a house on Cape Cod where we could woodshed for a few months in the winter before unleashing what was sure to be a revolutionary sound on Boston. Perfectest. Let the mad rock life begin…!

Except we weren’t allowed to have our girlfriends visit. And there was no drinking permitted in the house. And we subsisted on huge vats of underseasoned lentils. And if you’ve ever spent a few months in the offseason on the Cape, you’ll know that the sunny summer playground morphs into a lonely, forelorn, windswept wasteland that can be relentlessly corrosive to any sense of happiness and well-being. It may have been closer to a monastery than the dissolute, crazy-action life I thought I’d signed on for.

That said, Erik was an entertaining and charismatic character, his songs were cool, complex and challenging and Boby’s humor and sense of the absurd helped keep the entertainment factor high. We recruited a local guitarist whose unusual style earned him the nickname “The Alien,” put together a dozen songs, moved to a house in Brighton Center and decided to call ourselves Moving Parts.

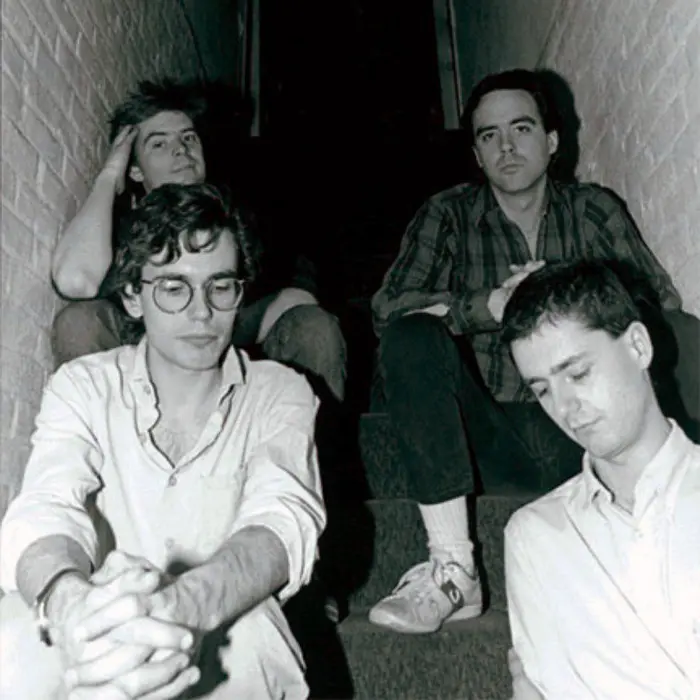

We were finding our way into the nascent art-school wing of the Boston music scene – playing gigs with Human Sexual Response, The Girls and La Peste – when I had an unfortunate encounter with an oil truck during the Blizzard of ‘78. Since that meant many months of recuperation, we had to stop playing together. The Alien decided this might be a good time to sneak back to the Cape and resume playing Joni Mitchell songs so Moving Parts placed an ad for a new guitarist in The Real Paper. A personable fellow showed up at the door with long hair and a bottle-green velvet frockcoat. There was a bit of confusion since he thought he was auditioning for bass but he said he was game for trying guitar.

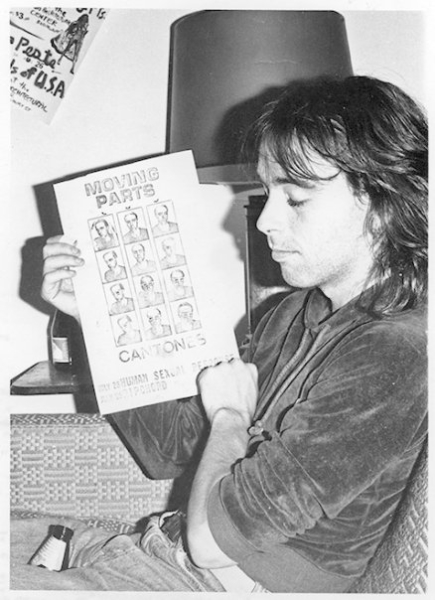

He said he was from Ann Arbor and that his name was Roger Miller. He played some startling whole-tone solos and told us he wrote music, too. The song he showed us that night was “Max Ernst.” I felt my life changing again.

(by Clint Conley)

Clint Conley was the bassist for Mission of Burma and a producer for WCVB-TV’s program Chronicle. He co-formed the band in early 1979 with Roger Miller and Peter Prescott and their first single was “Academy Fight Song” b/w “Max Ernst.”