Magical Nights at Club 47

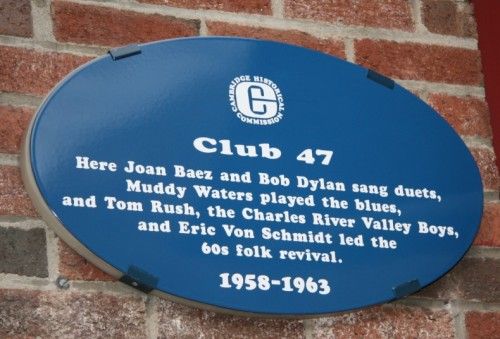

April 1963: On a Sunday night when I should have been sitting in the Harvard Law School library studying for first-year finals, I was standing in a long line waiting to get into a folk music club at 47 Mount Auburn Street in Cambridge, Mass.

I wasn’t much of a folk music fan, having grown up on Long Island as a rock ‘n’ roller listening to Alan Freed and Dr. Jive on the radio. My father had a large collection of classical music 78s, but mixed in with them were a few records by The Weavers, Leadbelly, Josh White and Cisco Houston. My mother liked to tell the story of how she bought lunch at a Horn & Hardart automat for a starving folk singer newly arrived in New York named Woody Guthrie.

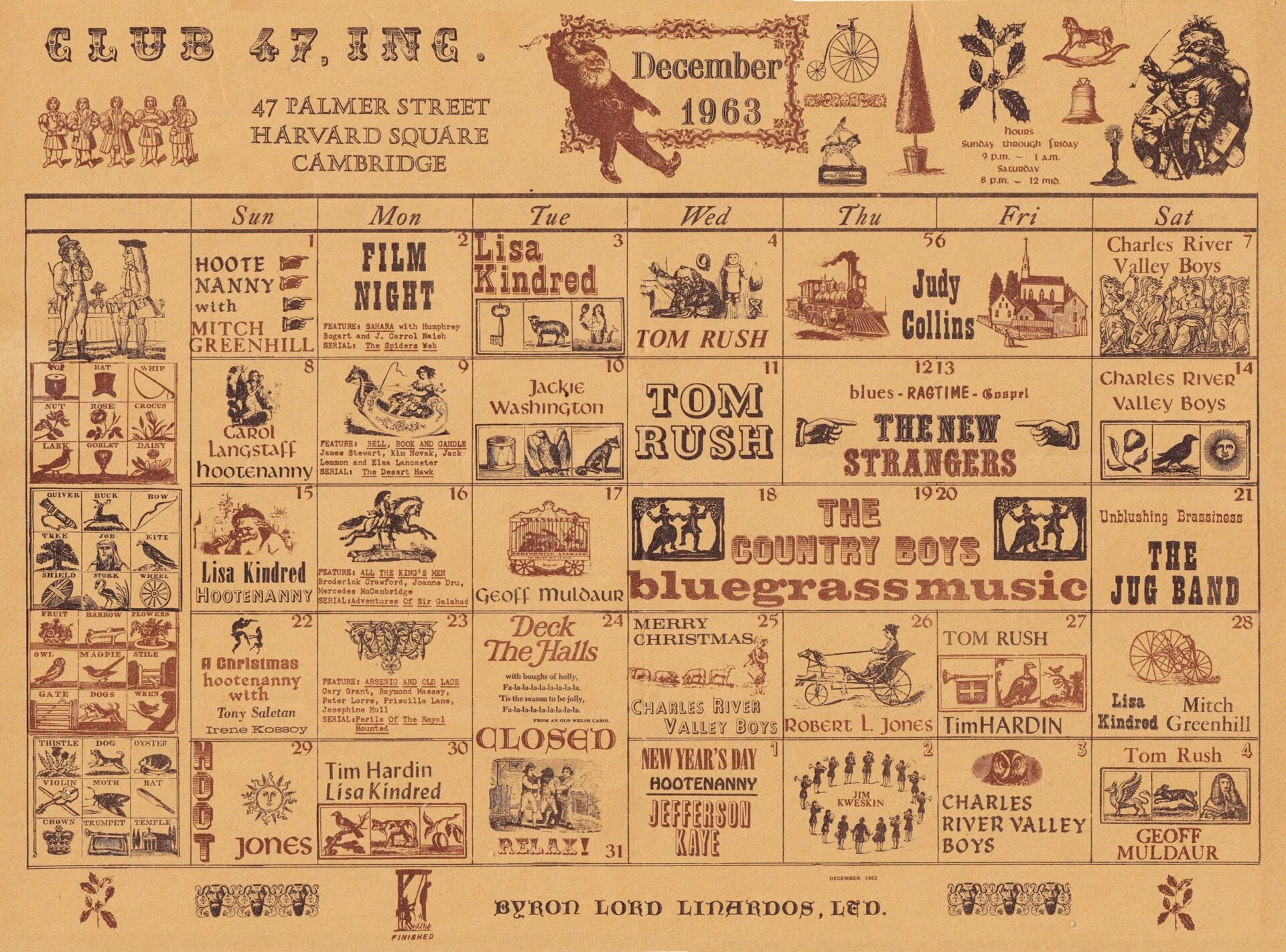

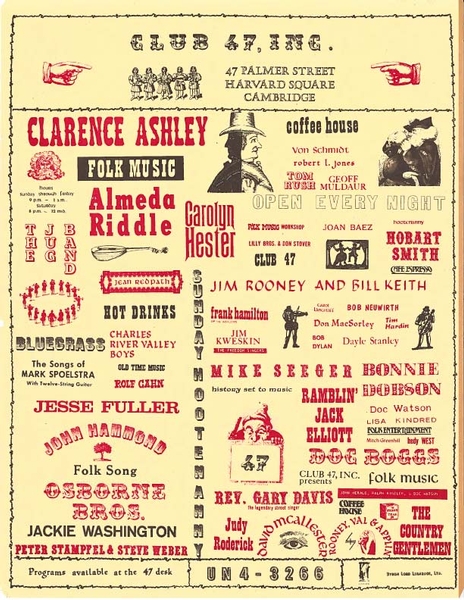

So I knew a little bit about folk music, but had never been to Club 47. I wasn’t even sure what I was doing there that night. But I’d picked up on the buzz around Harvard Square about a folksinger who was going to be appearing at the club. I’d never heard of him, yet somehow was drawn there. Like most Sundays, it was hootenanny night at the 47, when a succession of performers each did two or three songs.

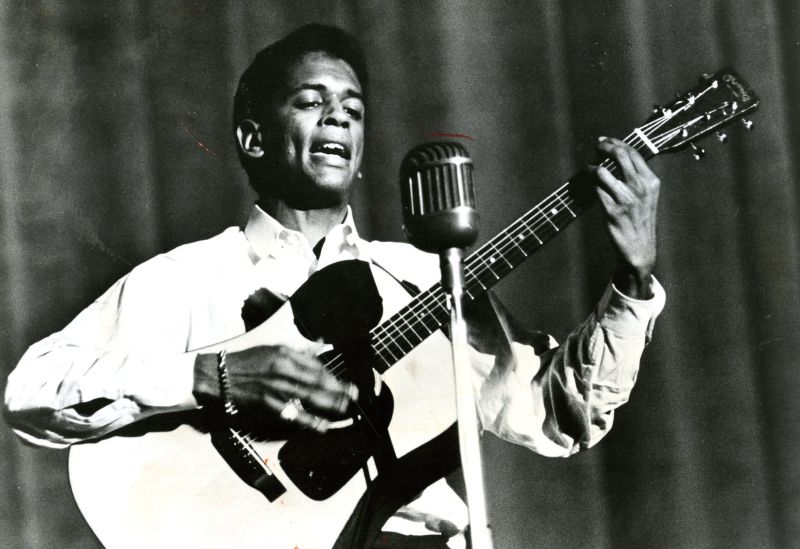

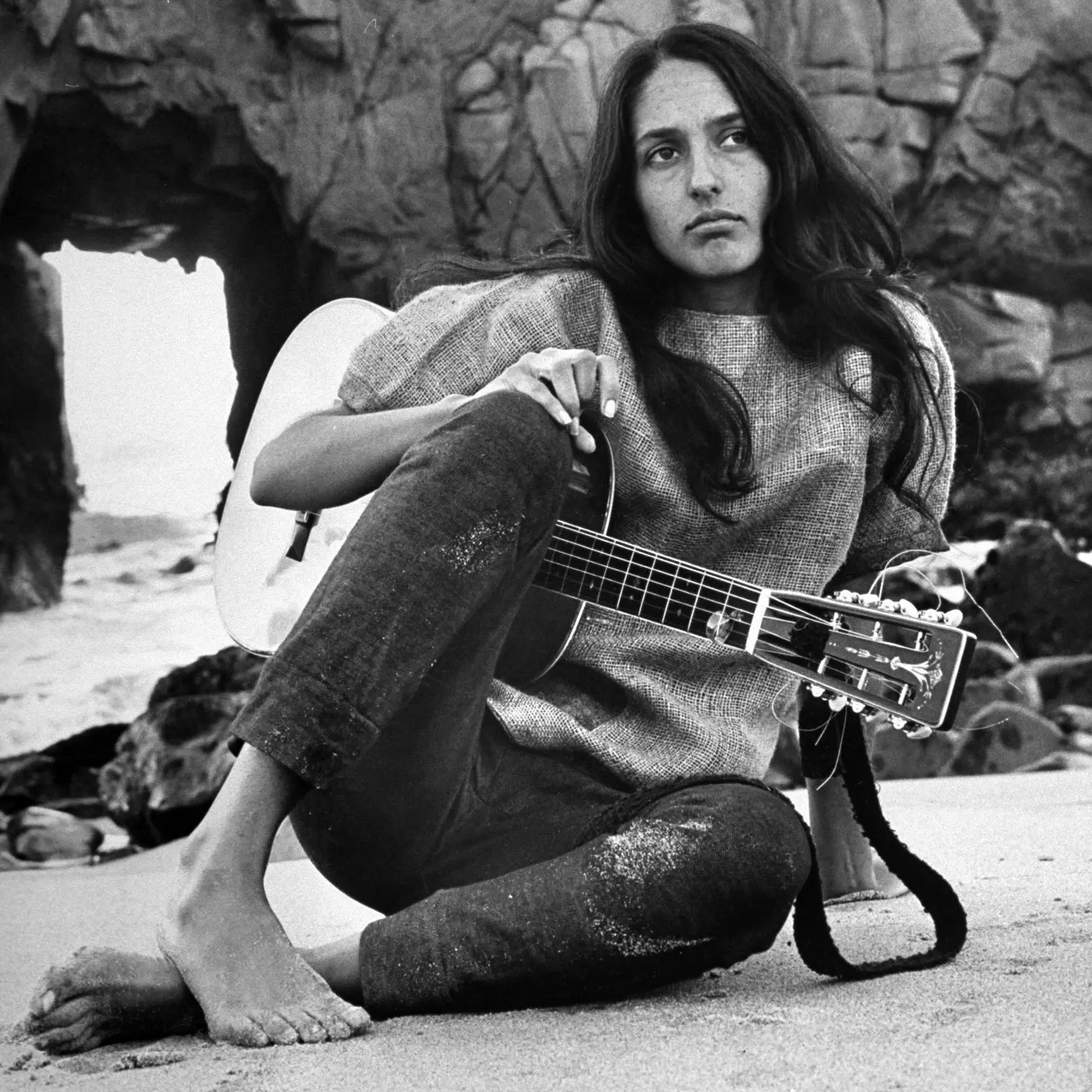

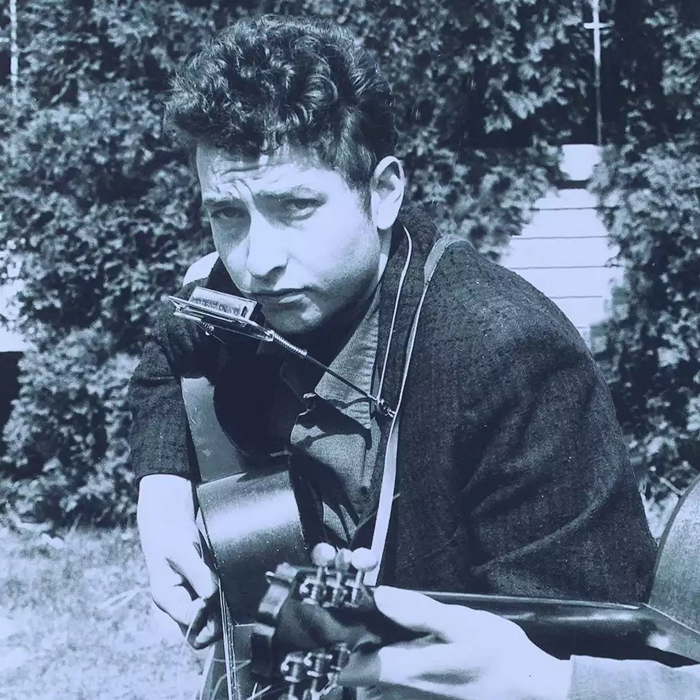

I didn’t know who they were, but the stars of the Cambridge/Boston folk scene came out that night at the hoot. It was a small room; the place was packed. At one point Joan Baez performed. I did know who she was. Then she introduced a scrawny little guy to do his turn. This was who everyone had been waiting for.

His last song, an antiwar anthem with searing lyrics, rang true after the Cuban missile crisis. But it was the power of his delivery that floored me. He was a folkie with an acoustic guitar, but his music hit me in the gut, like hearing Elvis sing “Heartbreak Hotel” for the first time. I’d never heard anything like it, half-sung half-spoken in a nasal voice while pounding out a repetitive rhythm on the guitar. The song was called “Masters of War,” his name was Bob Dylan.

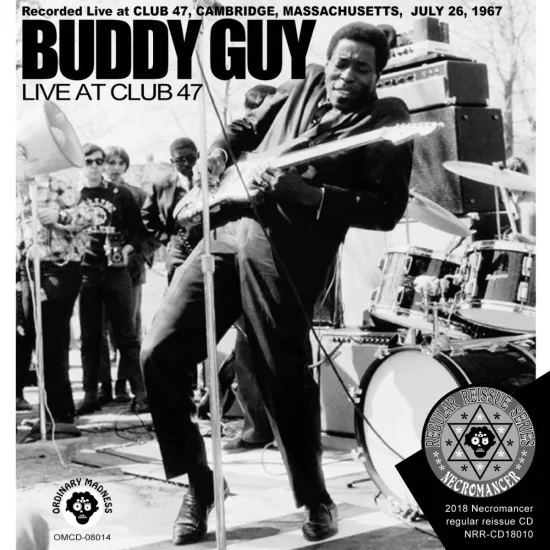

April 1967: After graduating law school and going to work in Washington, DC at the headquarters of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, I was back in Cambridge. I’d left my job and the law, a draft resister living in exile in Harvard Square. By now my musical tastes were expanding, thanks to Club 47.

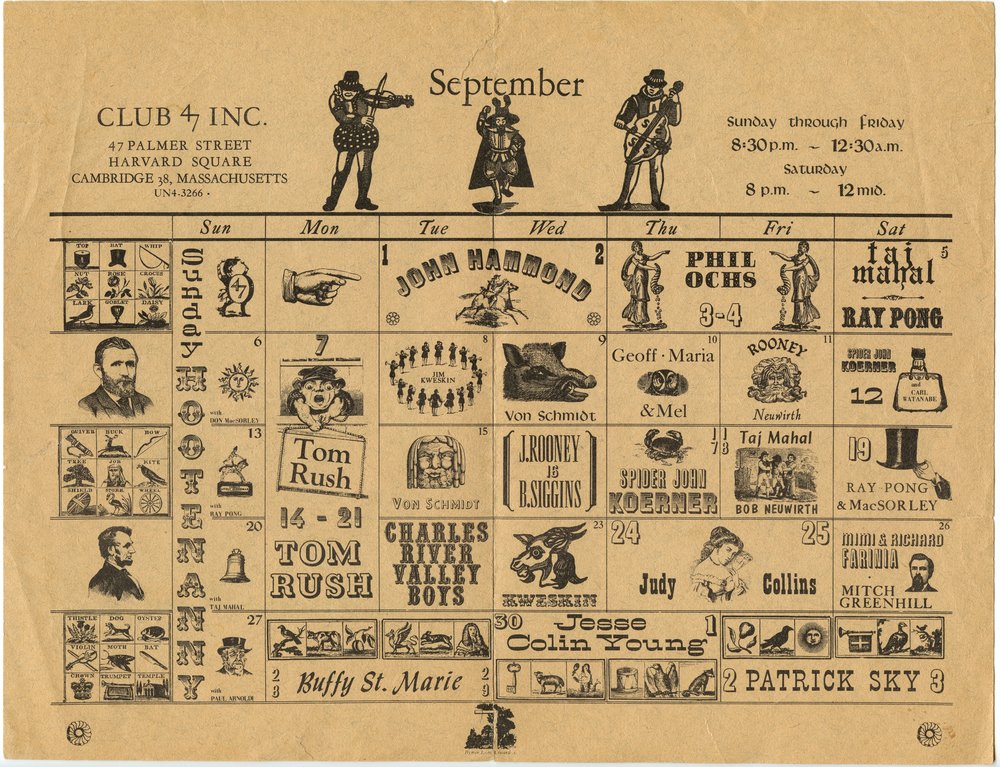

It had moved from its original location on Mt. Auburn Street to a space behind the Harvard Coop, downstairs at 47 Palmer Street. My life was in turmoil and I didn’t have much money, but admission was cheap, so I went there a lot to nurse a cup of tea and a light snack while listening to the music.

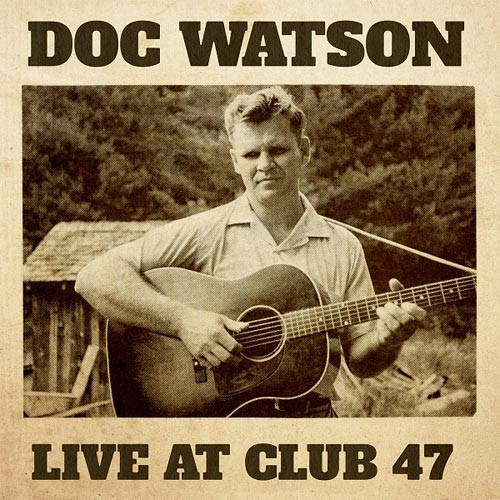

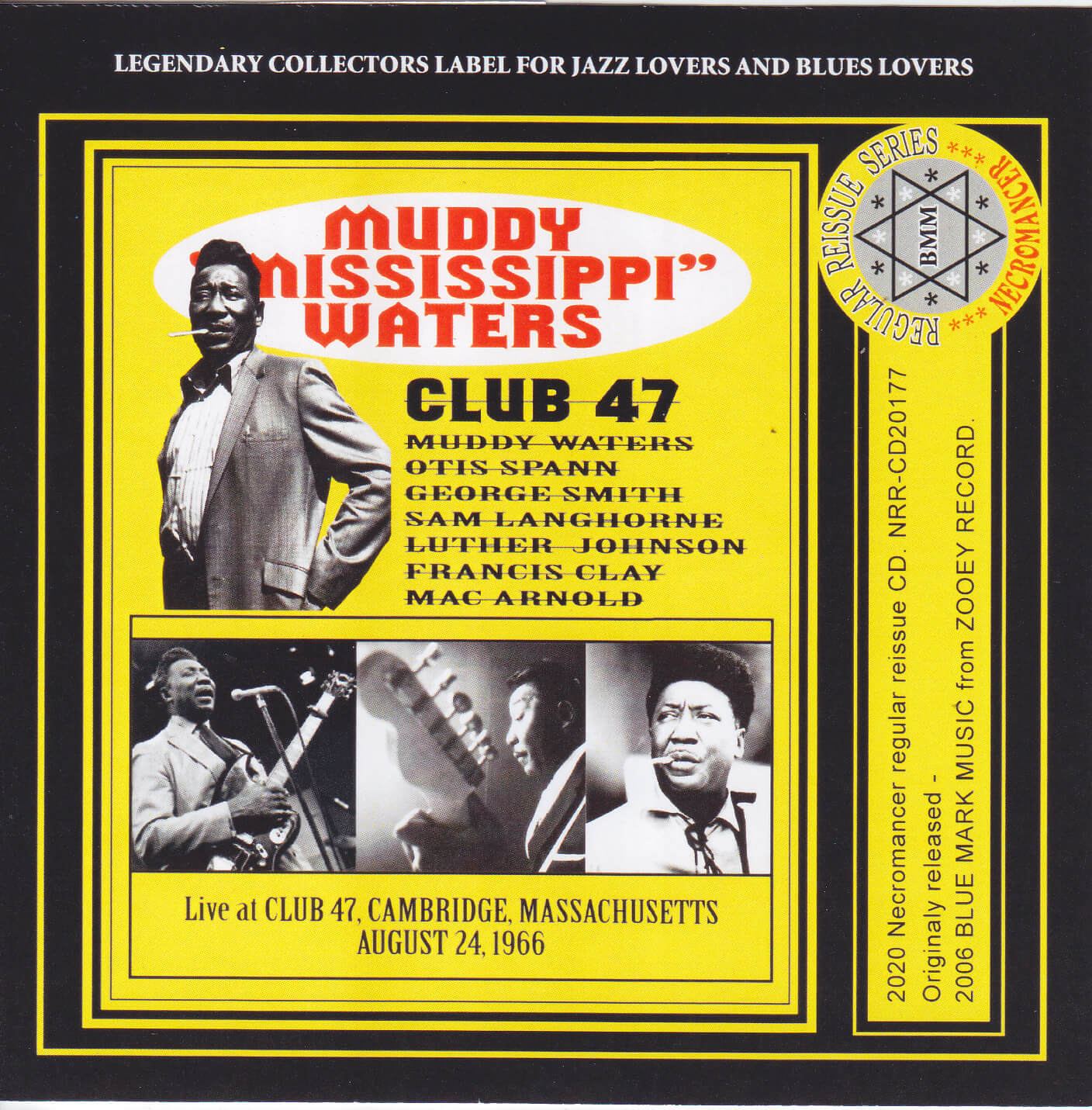

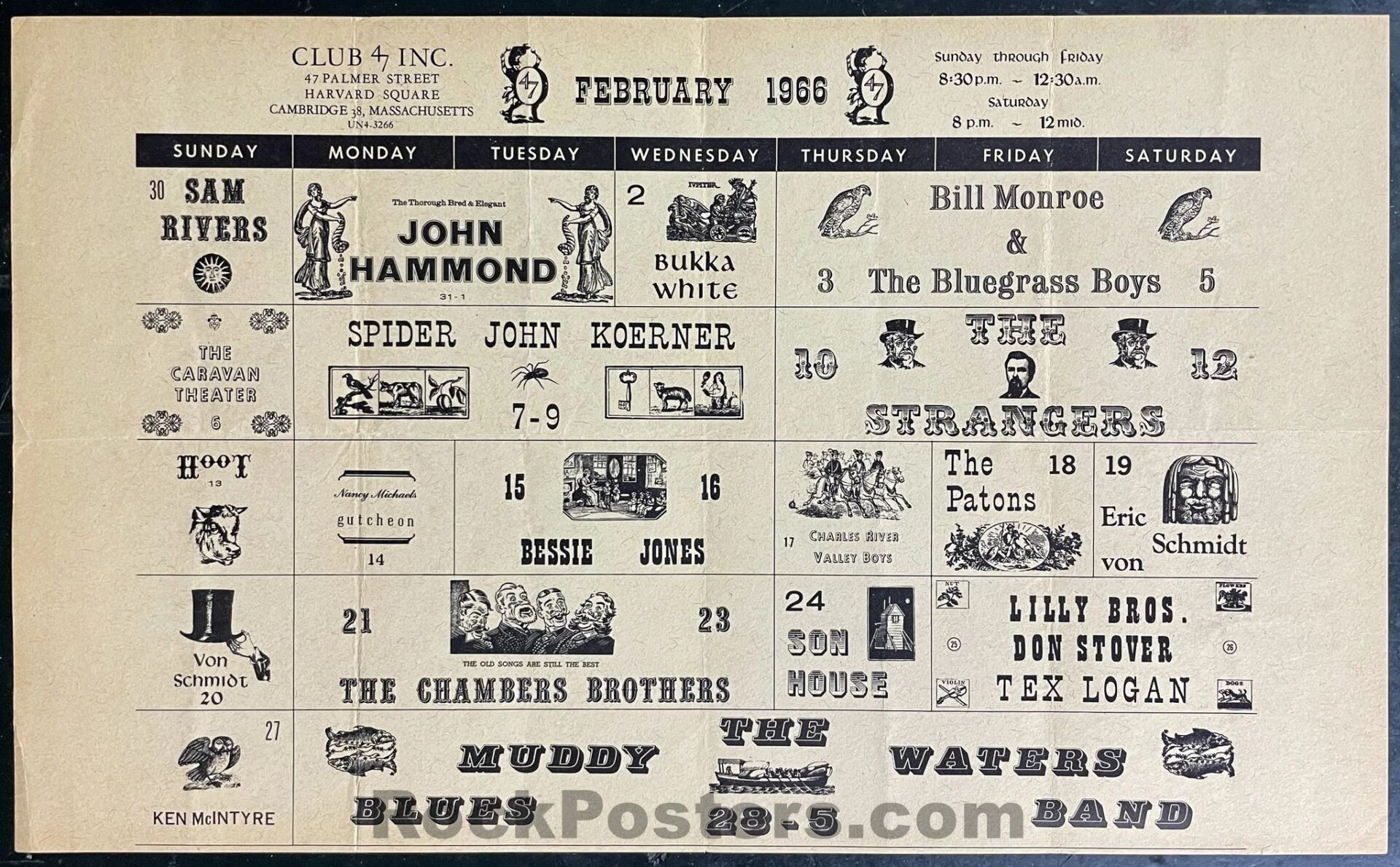

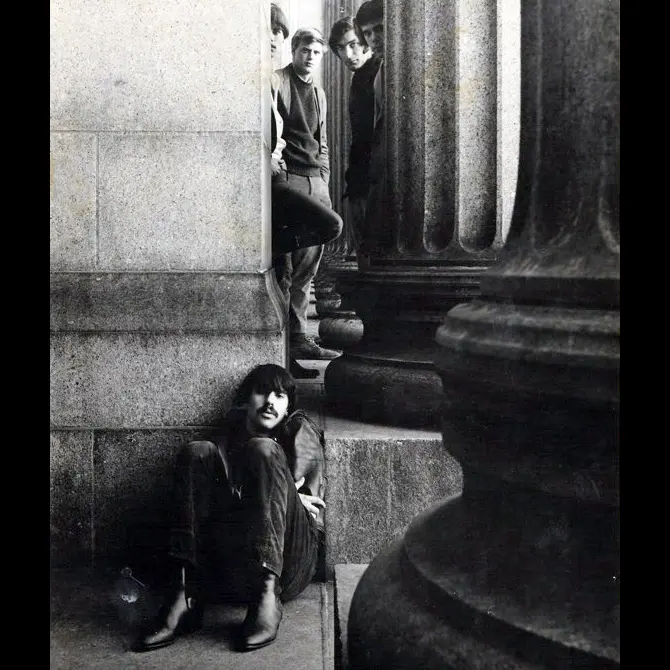

The lineup of performers that month was incredible. A young Joni Mitchell in a duo with her husband Chuck. 47 favorites Jackie Washington and Eric Andersen. It was the electric blues of Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker that drew me there, and I got turned on to the bluegrass picking of The Charles River Valley Boys and the good-time music of The Jim Kweskin Jug Band. It put a rare smile on my face to watch Fritz Richmond plucking a single-string washtub bass or huffing and puffing into a jug.

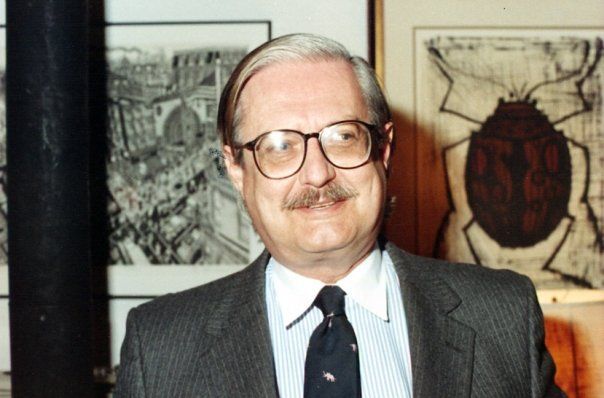

I also went to hear The Velvet Underground at The Boston Tea Party, a rock joint across the river. After the show I met one of the co-owners, Ray Riepen. When he decided a couple of months later to buy out his partner David Hahn, he needed to hire a manager. He talked with Jim Rooney about leaving his job as the manager of Club 47. But instead, Ray hired a guy with no experience running a club but who was into the kind of music the Tea Party audience wanted to hear – me.

April 1968: When I came on board, the Tea Party was open only on Friday and Saturday nights. But by the next spring, the club was so successful that we launched a series of shows on Thursdays, beginning on April 4th with Muddy Waters, followed by, among others, John Lee Hooker.

Club 47 shut its doors that month. I saw one of the last performances there, by Tea Party house band The Hallucinations, Peter Wolf’s first group. With a seating capacity of perhaps 100, the 47 was too small to afford to continue paying the acts who’d performed there over the years and to compete with new and larger venues like the Tea Party.

I felt a twinge of guilt for helping to put the club under by bringing many Club 47 regulars into the Tea Party: Muddy and John Lee, Howlin’ Wolf, Richie Havens, Eric Andersen, The Chambers Brothers. But at the same time, I believed those artists deserved a bigger audience and more money than they could get at the 47.

Ironically, the space at 47 Palmer Street reopened in 1969 as Passim, while the Tea Party closed down after 1970, unable to afford the escalating fees of rock bands that made big bucks at larger venues. Club Passim, now with its music school, has continued to this day to play a unique and vital role for generations of American folk music.

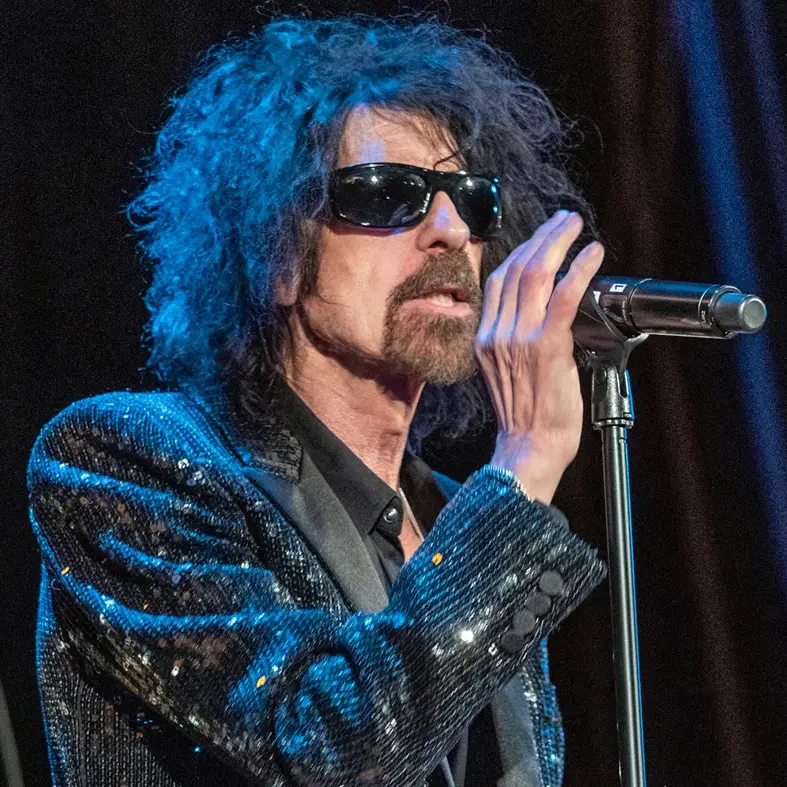

April 2006: The stars of the 1960’s Cambridge/Boston folk scene came out again one night at Club Passim to remember Fritz Richmond, who had passed away. It was amazing to hear them playing again in that room, a sad yet joyous celebration of Fritz and Club 47. They were joined by Fritz’s close friend John Sebastian, former leader of a rock band with jug band roots, The Lovin’ Spoonful (a name suggested by Fritz).

The Spoonful’s biggest hit was “Do You Believe in Magic?” At Club 47, we all did. There were so many magical nights there, none more so than that night for Fritz.

(by Steve Nelson)

Adapted from Steve Nelson’s memoir Gettin’ Home: An Odyssey Through The ‘60s (available from Amazon).

Steve Nelson was a co-founder of the Music Museum of New England.