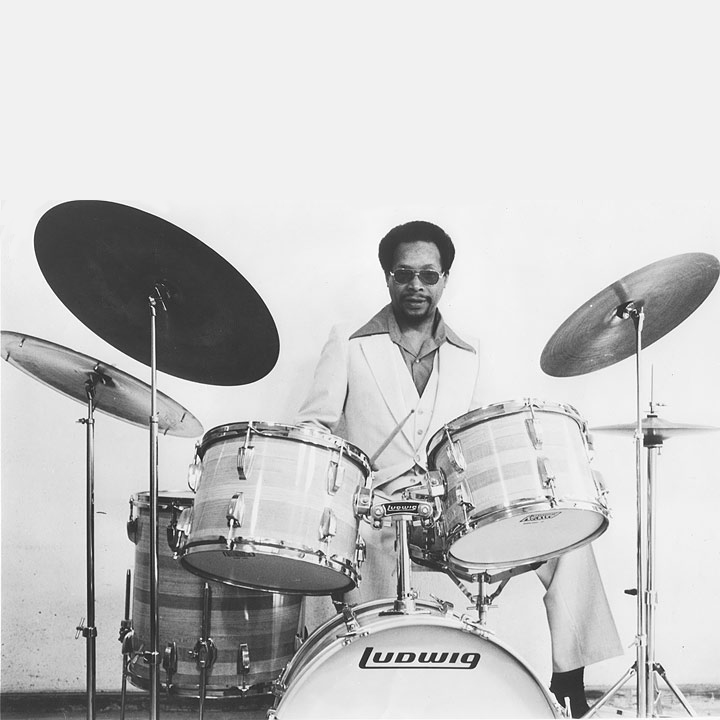

Lloyd Trotman

Consider these six songs, all of which rocketed up the charts and became defining examples of pre-Beatles American pop: Ray Charles’ “Mess Around” (#3, 1953), The Coasters’ “Yakety Yak” (#1, 1958), Jackie Wilson’s “Lonely Teardrops” (#1, 1959), The Drifters’ “Save the Last Dance for Me” (#1, 1960), The Tokens’ “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” (#1, 1961) and Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me” (#4, 1961).

Equally iconic and indelibly inked on the hearts and minds of music lovers across generations, each is unforgettable after a single listen, an earworm with all the essential elements that turn a simple tune into an instant classic. And they have one other thing in common: the double bassist from Boston who played on them all.

Overview

With impeccable intonation, an uncanny ability to weave complex patterns into basic grooves and a gift for bridging ‘60s-pop orchestration with ’50s-era doo-wop harmonies, Lloyd Trotman helped establish the bass lines that remain the bedrock of blues, soul, R&B, jazz, pop and rock today.

After cutting his teeth in various Boston jazz clubs from his mid-teens to mid-20s, he moved to New York City in the mid-1940s and soon became a first-call session cat for labels including RCA Victor, Mercury, King, Okeh, Vik, Cadence, Brunswick and Atlantic. During that time, he worked alongside a multigenred assortment of artists accurately called “legends” including Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, James Brown, Sam Cooke, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, The Isley Brothers, Jimmy Witherspoon, Paul Anka, Bobby Darin, Neil Sedaka, The Platters, Big Joe Turner, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, The Moonglows and The Everly Brothers.

Musical beginnings

Born in Boston on May 25, 1923, and raised on Shawmut Street in Boston’s Bay Village neighborhood, Trotman was surrounded by classical music at home. He studied piano from age four to age 12 at the school that his father ran, Music Lovers’ School for Music & Drama, which sponsored and hosted concerts, theatre productions and dances, mostly in Boston’s South End. “That’s where I learned harmony, solfeggio, how to read the notes, all the tone-appreciation things that go along with playing music,” Trotman said in tapes he recorded in 2006.

His passion for the double bass – and ensuing disinterest in piano – ignited when he was 12, sparked by listening to the symphonic ensemble his father led while they rehearsed in his family’s living room. “That’s when I first heard the big bass violin,” he said. “When the bass player drew that bow across the strings, it sent a thrill through me which I will never forget. I was hooked and knew I was destined to play that instrument.”

Unable to afford a double bass of his own, he joined his school’s student orchestra since they provided an instrument and offered weekly lessons for members. “From then on, it was practice, practice, practice,” he said. “My dad was a bit disappointed in me for [switching from piano to double bass] because he thought I’d developed quite a skill as a piano player, but I knew how I felt so I just went ahead with it.”

Going pro at age 14

In 1937, 14-year old Trotman’s professional music career began when he joined locally renowned bandleader Tasker Crosson’s orchestra – in which pianist Sabby Lewis had played and drummer Alan Dawson played several years later – after Crosson’s original bass player was drafted into the military. “He left his bass behind for me to use,” Trotman said. “That was my own basic training in bands, thanks to him.”

About two years later, while still below the legal drinking age – then 17 in Massachusetts – he moved to what jazz historian Richard Vacca has called “probably Boston’s best band then,” The Alabama Aces, led by Joe Nevils. He remained with the group for two years, gigging at top Boston clubs like the Savoy Cafe, the Roseland-State Ballroom and The Hi-Hat .

First tour, The Joe Nevils Sextet, USO performances

In 1940, just weeks after finishing high school, Trotman toured the US with jazz singer Blanche Calloway (Cab Calloway’s older sister), then returned to Boston to join Nevils’ newly formed sextet. He stayed with the group for the next five years, gigging in Boston for the most part, while taking classes at New England Conservatory.

In 1944, when he turned 21, he received draft orders but didn’t pass the physical exam because of a nervous stomach condition. Though he never served in uniform, from early 1944 until the Japanese surrender in August 1945 he played shows for free with a number of bands at the USO centers in Massachusetts and Connecticut. “I felt good that I was able to do my part for the war effort in this way,” he said.

Move to New York City

In mid-1946, the 23-year-old stage veteran – who hadn’t played on a single record, was recently married and had a newborn daughter – moved to New York City, thinking it was the best place for any serious jazz musician to achieve long-term financial stability. “When I got married and became a father, I knew that I would have to move to New York to make a living,” he said. “So, I went over to those 52nd Street jazz clubs and I got work with [violinist] Stuff Smith, [saxophonist] Pete Brown and [trumpeter] Charlie Shavers, then started backing Billie Holiday, playing clubs like the Copacabana, The Zanzibar, The Three Deuces, The Metropole Cafe, that kind of thing.”

No interest in bebop

The bebop era was nearly in full swing by the time Trotman arrived in the Big Apple, but he had no particular interest in jazz’s newest subgenre. “It really did not appeal to me musically,” he said in the 2006 tapes. “It featured a whole lot of notes but no identifiable melodies. It just showed off the great skills of the players.”

Trotman was highly regarded for the eloquence of his own melodic approach, which he said was influenced Jimmy Blanton of the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra and Leroy “Slam” Stewart – the latter of whom trained at Boston Conservatory (now Boston Conservatory at Berklee) – and was inspired by the Dixieland and the Latin rhythms he’d discovered during his years with Crosson’s and Nevils’ orchestras.

The Duke Ellington Orchestra

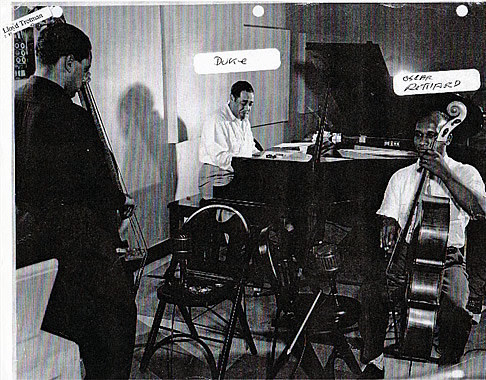

Within several months of arriving in New York, Trotman landed the gig of a lifetime: Duke Ellington chose him to replace Junior Raglin, based on a strong recommendation from Skippy Williams, a member of Ellington’s band in 1943 and 1944. He stayed with Ellington for only four months, however, deciding that being close to his wife and baby daughter was his top priority. “I didn’t want to spend nine months of the year on the road,” he said.

Despite the extremely brief tenure, Trotman often told reporters that he owed everything in his later career to the opportunity Ellington provided. His months with the Duke led to him being named one of Esquire magazine’s “New Stars of 1947,” an accolade the ever-reserved Trotman said he appreciated but never let go to his head.

Apollo Theatre house band, Early recordings

After leaving Ellington’s orchestra, he played in the house band at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, recorded with bassist/cellist Oscar Pettiford and worked with other artists including bandleader Woody Herman, singer/pianist Hazel Scott, pianists Bud Powell and Billy Taylor and saxophonists Boyd Raeburn and Al Sears. In the late ‘40s, he performed in Boston multiple times at venues including Wally’s Paradise (now Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club) and in 1950 he played in the sessions that resulted in Ellington’s LP Good Times! (issued in 1964 by Riverside Records).

Johnny Hodges All-Stars, The Coronets

In 1951, Trotman joined The Johnny Hodges All-Stars, recording tracks for their album Castle Rock that year (issued in 1955 by Norgran Records) and appearing with the group for one-week stand at Storyville in Boston in May. Also in 1951, Trotman cut four sides for Mercer Records as part of The Coronets, a septet comprised of Ellington’s current and former sidemen, in Boston at Trans Radio Productions, then located at 178 Tremont Street.

Notable session work, Notable hit songs

Trotman’s period with the Cambridge, Massachusetts-born Hodges provided him with the exposure that “likely got him into the studios,” according to jazz historian Vacca, author of The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Troy Street Publishing, 2012). With his far-reaching repertoire, expertise in multiple rhythmic styles and superb sight-reading skills, Trotman was one of the most in-demand session players in New York City from the early ‘50s through the late ’60s.

His bass lines formed the foundation for jazz, blues, boogie-woogie and R&B sessions with artists including pianists/vocalists Viola Watkins and “Champion Jack” Dupree, vocalist Pleasant ”Cousin Joe” Joseph, guitarists/vocalists Mickey and Sylvia, bandleader “Lucky” Millinder, Ray Charles and Ben E. King, among others.

In addition to the songs mentioned already, Trotman was the double-bass-tone backbone on Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll (#1, 1954), The Moonglows “Sincerely” (#1, 1954), Screamin’ Jay Hawkins‘ “I Put a Spell on You” (#80, 1956), The Platters’ “My Prayer” (#1, 1956), The Isley Brothers’ “Shout” (#47, 1959), Dinah Washington’s “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes” (#1, 1959) and Sam Cooke’s “Chain Gang” (#2, 1960).

Newport Jazz Festival, Rock & Roll Orchestra, Solo album

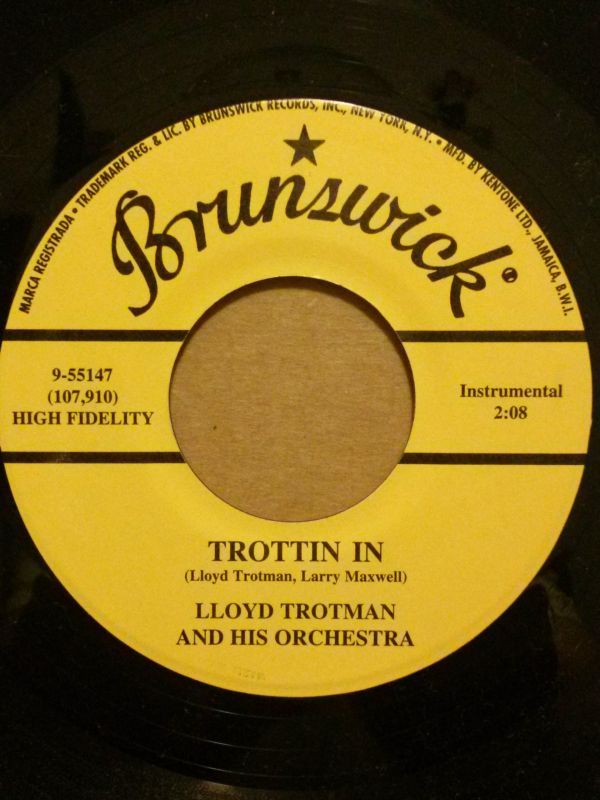

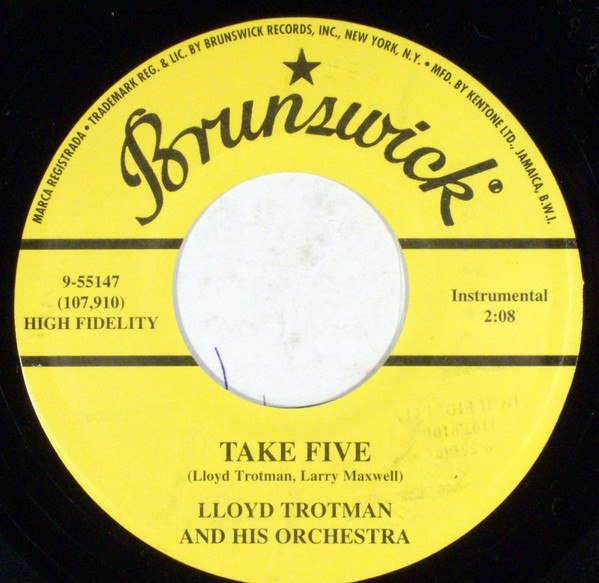

In addition to his studio work, Trotman appeared at the Newport Jazz Festival three times (with different ensembles) and was part of Alan Freed’s Rock & Roll Orchestra in the late ‘50s. In 1959, he recorded a disc under his own name for Brunswick that featured two originals, “Trottin’ In” and “Take Five,” the latter completely unrelated to the famous Dave Brubeck track also released that year.

Retirement, Death

By 1969, demand for double bassists had plummeted and the lucrative pop-music sessions centered in New York City had begun migrating to Los Angeles. With work drying up, Trotman decided to walk away from the studio altogether – at age 47. Some theorized that his surprisingly early retirement was the result of his never having switched to electric bass; others said he was simply tired of the daily commute from Long Island, where he’d lived since 1962.

Trotman continued making live appearances and in the mid-‘70s he formed a duo with English pianist Henry “Billy” Roland, former sideman for Benny Goodman and Perry Como. When Roland died in 1985, 62-year-old Trotman retired from being a full-time musician and took as job as a teller at the Bank of Long Island, eventually becoming a loan officer. He played occasional gigs on weekends with various combos until he passed away at age 84 on October 3, 2007.

Career reflections

Reflecting on his nearly five-decade career in the tapes he recorded in 2006, Trotman said he was fortunate to be able to provide people with the unique joy that music brings. “Music is one of God’s most wonderful gifts given to us along with life and breath,” he said. “It adds joy to almost everything in our lives. I have been blessed with the gift of music and I am so happy and grateful that I developed the talent to pass it on for all to enjoy.”

(by D.S. Monahan)