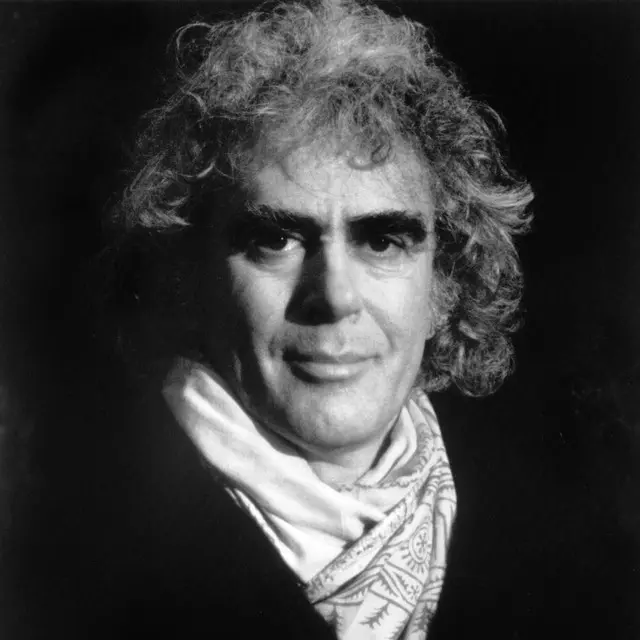

Jaki Byard

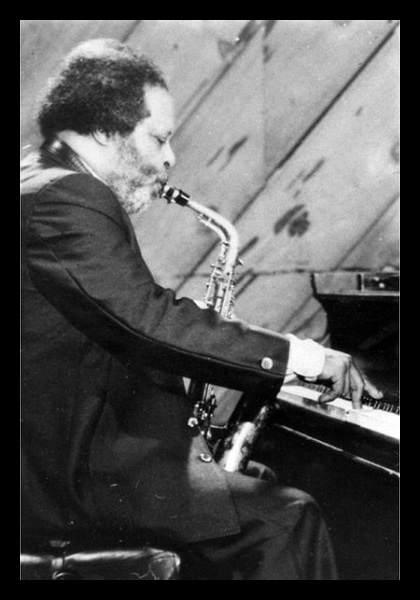

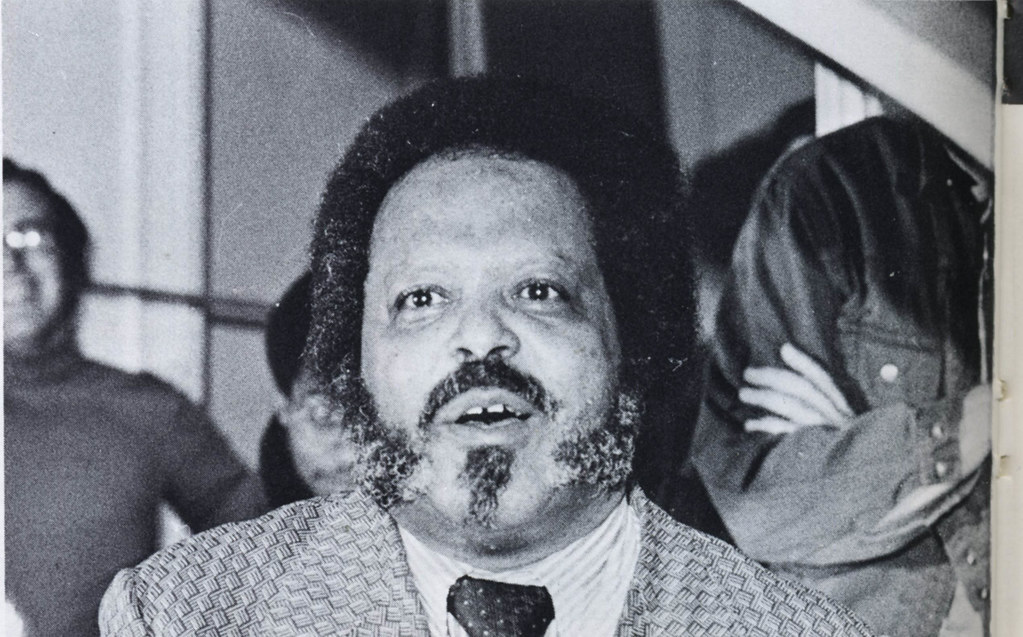

By all accounts, and putting the music aside, Jaki Byard was the type of person everyone just wanted to be around. To all that knew him, his wit, incredible sense of humor and general positivity no matter what the situation, were truly remarkable traits that spoke volumes about the man. The fact that Byard was a true musical genius was just another area where his greatness was on display, and obvious to everyone that has ever listened to the multi-instrumentalist’s unique style and delivery.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, MILITARY SERVICE, CANNONBALL ADDERLEY

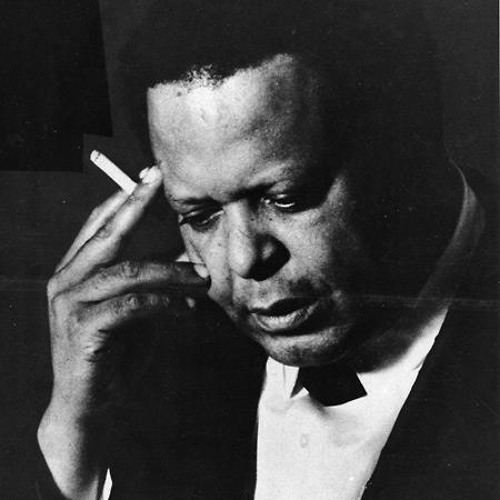

Byard was born John Arthur Byard Jr. on June 15, 1922 in Worcester, Massachusetts, and both of his parents played instruments, his father the trombone and his mother the piano. Growing up with music being a main theme around his house, it was perfectly natural that Byard started taking piano lessons at age eight.

Byard was inspired at an early age by big band and swing music, and those influences were reflected in the distinctive style of jazz for which he became known. Unfortunately, the Great Depression forced his family to discontinue his piano lessons, so young Byard began playing a trumpet that belonged to his dad. During these early years, he also spent as much time as possible going to concerts in Worcester (often at Lake Quinsigamond) to see Benny Goodman, Chick Webb, Fats Waller and other jazz greats, which led to him falling in love with and mastering trombone, saxophone and drums.

Like millions of his contemporaries, Byard was drafted into the Army 1941, at age 19. The only positive side was that he was paired in the service with Earl Bostic, with whom he collaborated in later years Byard studied music theory while in the military as well as the works of classical composers such as Chopin and Stravinsky. While serving, he met Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, who became something of a tutor to the young saxophonist.

EARLY BANDS, SOLO ALBUMS, CHARLES MINGUS, EDWARD DOLPHY

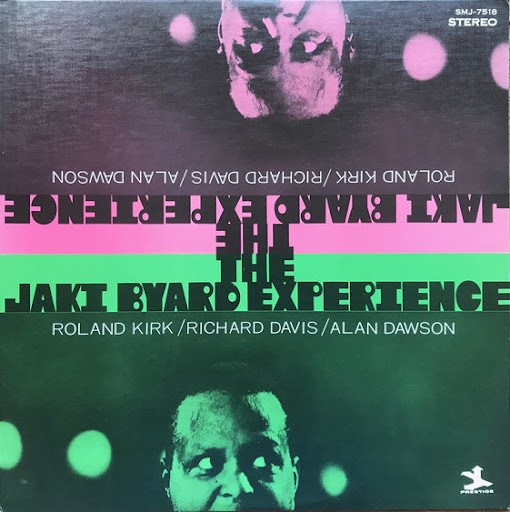

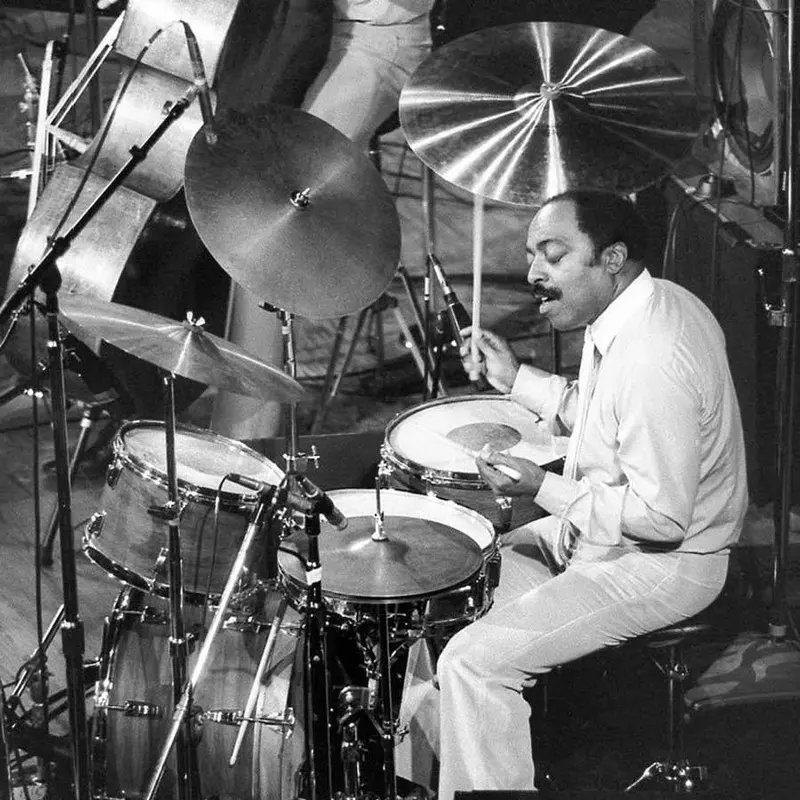

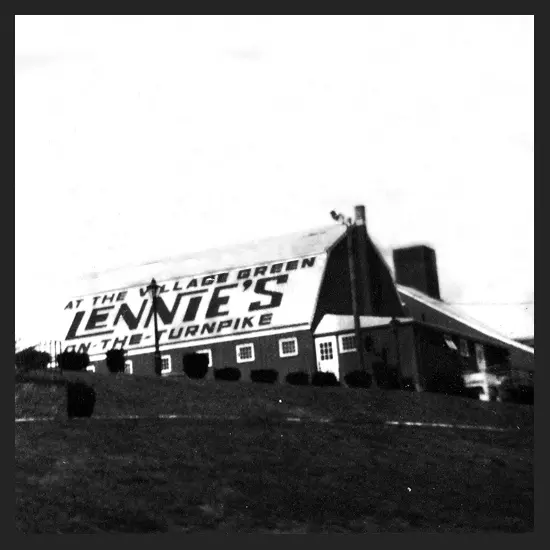

Byard’s military service ended in 1946, and his career started gaining traction until the late ‘40s and early ‘50s; the list of prominent musicians that he played with during this period seems almost endless. He joined Bostic’s band in 1947, then returned to the Boston area and played with Joe Gordon and Sam Rivers, eventually joining forces with Charlie Mariano and playing gigs in Lynn and West Peabody at Lennie’s on the Turnpike. From there, Byard played tenor saxophone in Herb Pomeroy‘s band for three years, recording with him in 1957. His first solo effort was 1960’s Blues for Smoke; other albums in a trio format soon followed, including 1964’s Out Front! (with Roy Haynes on drums on one track). He played piano on Charles Mingus’s 1963 offerings The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady and Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus.

His work on Eric Dolphy’s debut album Outward Bound (New Jazz, 1960) is regarded as a true classic among Jazz aficionados. The mystifying reality was that despite being a tremendously talented multi-instrumentalist and playing with some of the most prominent musicians of his day, Byard never got the recognition one would expect. He remained relatively ignored outside of the inner circles of the Jazz world.

NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY, DUKE ELLINGTON, AWARDS, DEATH

Byard was always known to put a high value on and its vital role in any artist’s development so it is no coincidence that he became a professor at New England Conservatory and several other institutions, giving his students instruction and insights based on his experience and deep knowledge of his craft. His former bandleader Herb Pomeroy, who’d become a Berklee College of Music professor, recognized Byard’s teaching talents publicly, calling him “the force behind younger musicians in Boston learning about the changes in music.” While at New England Conservatory, Byard continued to tour and fill in for Duke Ellington on piano when needed. In 1979, the formed a New York City-based big band called The Apollo Stompers.

In 1988. Boston Mayor Raymond Flynn awarded him the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Award for Outstanding Contributions in Black Music and Presence in Boston and in 1995 New York City Mayor Rudolph Guliani presented him with an award for his contributions with The Apollo Stompers. Tragically, Byard was shot and killed in his home in Queens in 1999 in a bizarre (and still unsolved) homicide. He’s missed by his family, his students, fellow musicians and all the others who knew him, but the legacy of the both man and his music will live on forever.

(by Mark Turner)