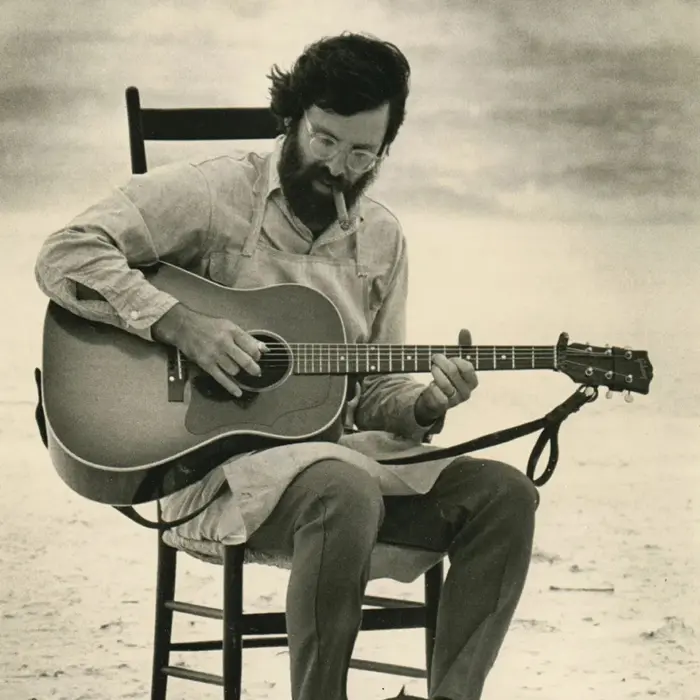

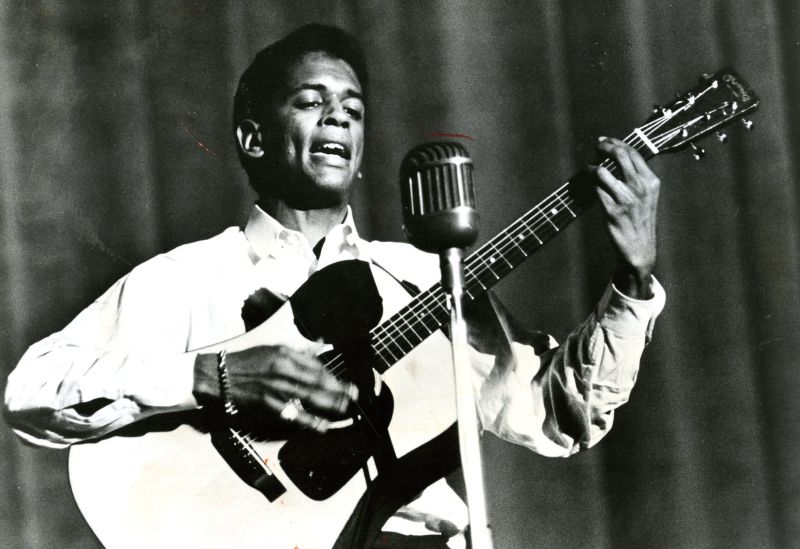

Jackie Washington

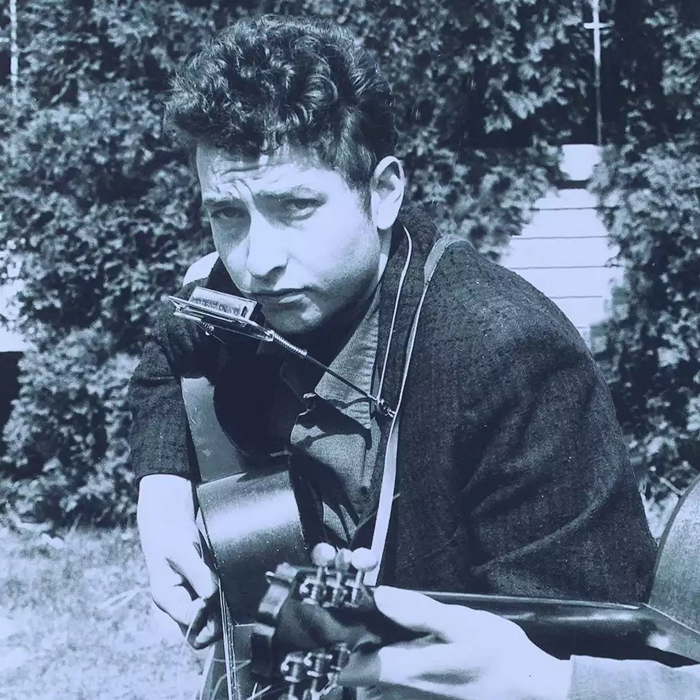

Despite his indisputable contributions to the thriving Cambridge folk scene in the ‘60s and the major influence Bob Dylan and Joan Baez have said he had on their own work, singer-songwriter Jackie Washington’s entirely undeserved fate seems to be that he’s either confused with the Canadian bluesman of the same name or forgotten altogether.

Like treasured rare coins that have somehow fallen between the floorboards of time, none of the four albums he recorded for Vanguard Records in the ’60s are available on CD or any other digital format. And the first page of nearly every web search for “Jackie Washington” lists sites about the Ontario-born blues singer, not the Puerto Rico-born folk singer.

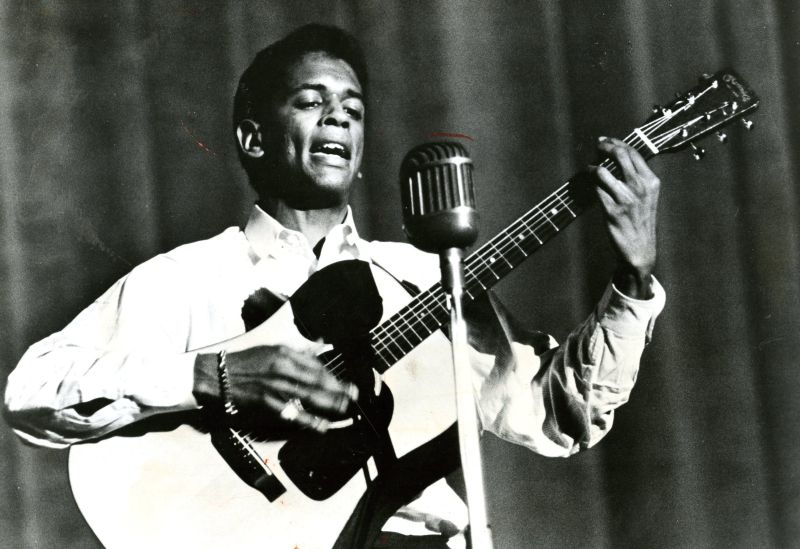

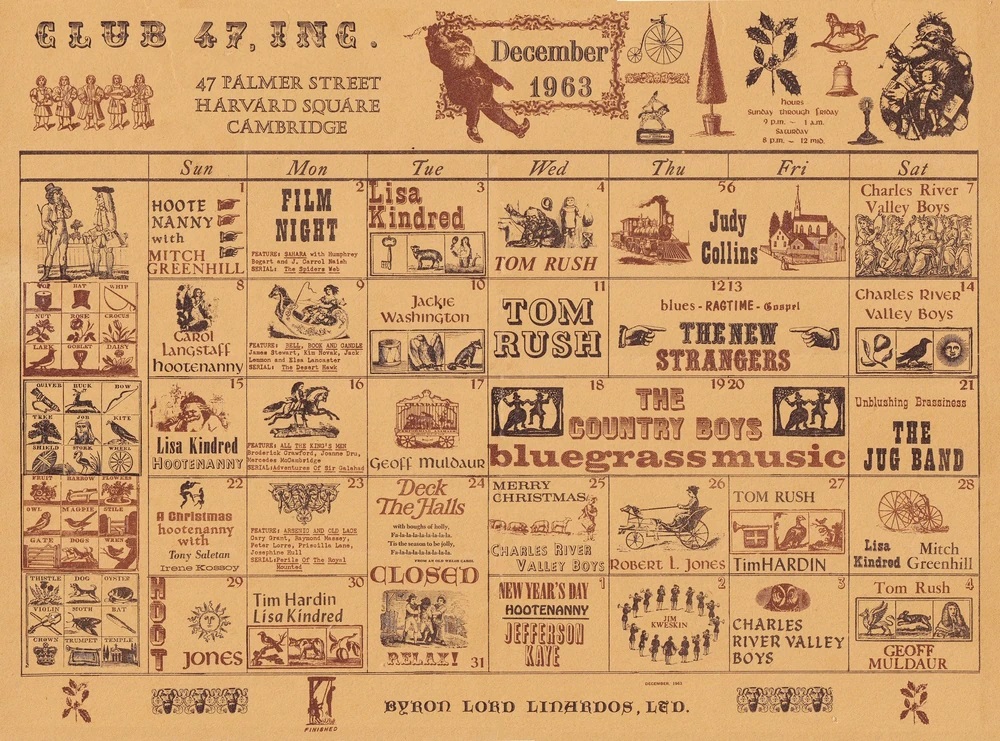

Though never viewed as a particularly strong songwriter in his own right, Washington’s uncanny ability to rework folk ballads across a broad range of traditions – combined with his onstage charm and wit – made him one of the most frequent performers at Cambridge’s Club 47 from 1962 to 1967. During that time, he grabbed the attention and gained the respect of folk icons like Dylan, Baez and Eric von Schmidt in addition to countless other artists and music lovers.

Musical beginnings

Born Juan Cándido Washington y Landrón on June 2, 1938, in Puerto Rico and raised in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Washington grew up surrounded by a wildly eclectic range of music and – unlike his white contemporaries – he was steeped in what’s now called “world music” long before he started playing guitar at age 13. His family played records by Puerto Rican artists like “the king of Jíbaro music” Ramito and singer-bandleader Tito Rodríguez plus Mexican bolero trio Los Panchos while listening to Bing Crosby, contralto Kate Smith and singer-trumpeter-bandleader Vaughn Monroe on the radio. Washington has said that he listened to the Grand Ole Opry “religiously.”

“I’m a Puerto Rican black man, and folk music was not something I ‘discovered’ at Club 47,” he said in 2014. “It was part of my daily life and the lives of my family and neighbors. I’d heard gospel music and R&B hits blared from speakers in the record stores where they sold tickets to those artists’ shows. I was familiar with the music of people like Clara Ward and the Ward Singers, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and the Blind Boys of Alabama. At the parties I attended I heard records of Johnny Ace, the Clovers and Ruth Brown. I loved folk music, but I also liked Dean Martin, Harry Belafonte, Eartha Kitt and I loved Pearl Bailey. And I could listen to all of that at the same time. I didn’t think it had to be separated or pigeonholed.”

Emerson College, Debut album, Dispute with Dylan

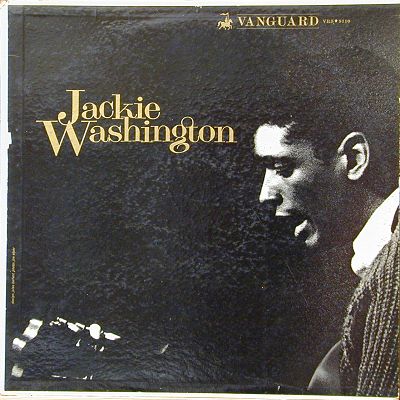

In May 1960, while a Theatre Arts major at Emerson College, Washington made his debut at the Indian Neck Folk Music Festival in Branford, Connecticut, along with 19-year old Dylan and a clean-cut quintet formed in 1958 at Wesleyan University, The Highwaymen. By March 1962, he’d built such a loyal following that he began a five-year stretch playing at least four times per month at Club Mount Auburn 47 – which became Club 47 in 1963 and Passim in 1969 – and signed with Vanguard, which released his self-titled debut in 1962. Manny Greenhill, the founder of Folklore Productions, managed Washington and Baez – and later Livingston Taylor – and Vanguard promoted Washington as Baez’s male version.

In August 1962, Washington debuted at Gerde’s Folk City in New York, starting what in the folk community was a well-known a dispute between him and Dylan, who was in the audience that night and whose eponymous debut Columbia had released in March that year. According to Washington in Baby, Let Me Follow You Down: The Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years (co-written by von Schmidt and Jim Rooney), Dylan asked Washington to replay his rendition of the standard “Nottamun Town” several times and in May 1963, when Columbia released Dylan’s second LP, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Washington claimed the song “Masters of War” was a blatant rip-off of his “Nottamun Town” arrangement. Though he never sued Dylan, he swung back passive-aggressively in his self-penned 1967 song “Long Black Cadillac,” an obvious parody of Dylan’s 1965 classic “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Jackie Washington/Vol. 2, Newport, Jackie Washington at Club 47

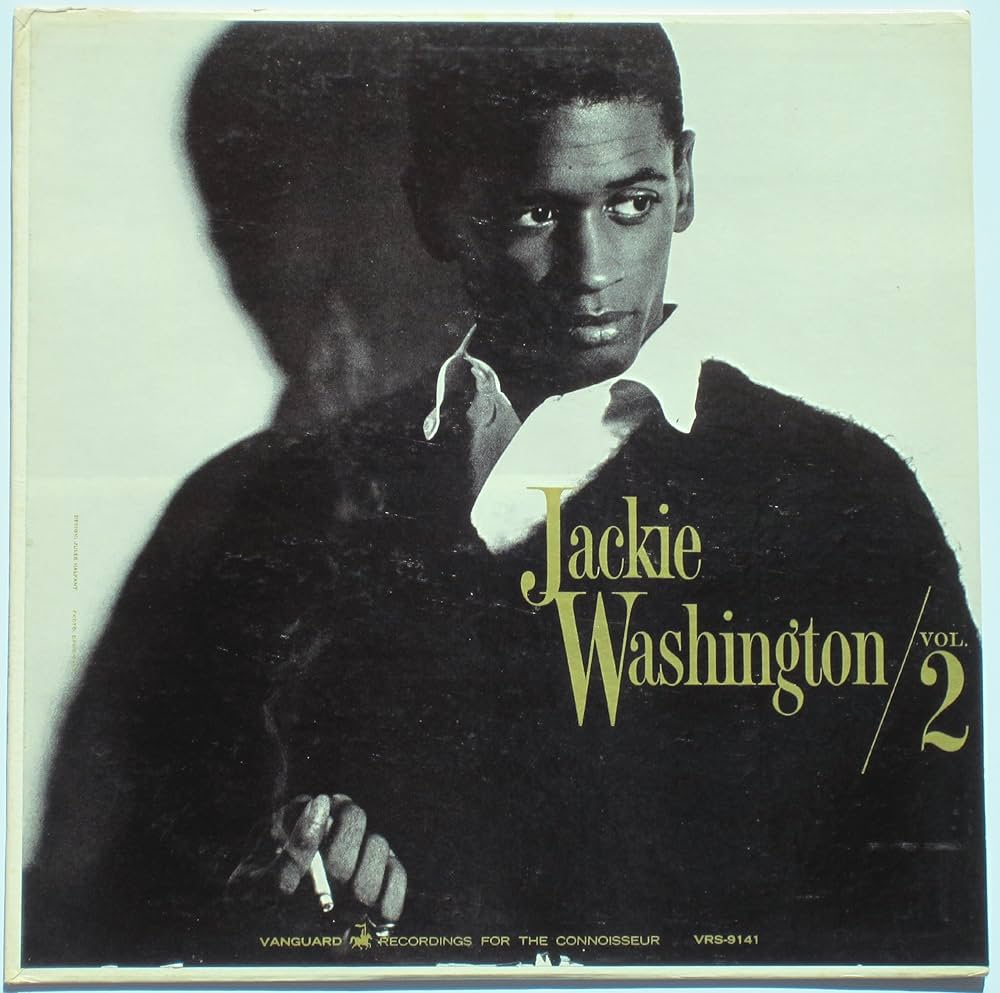

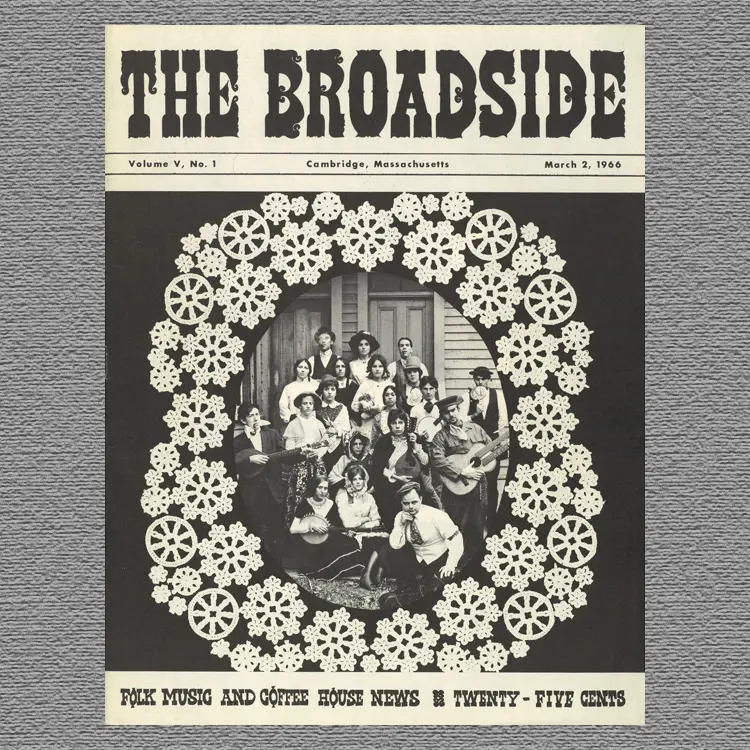

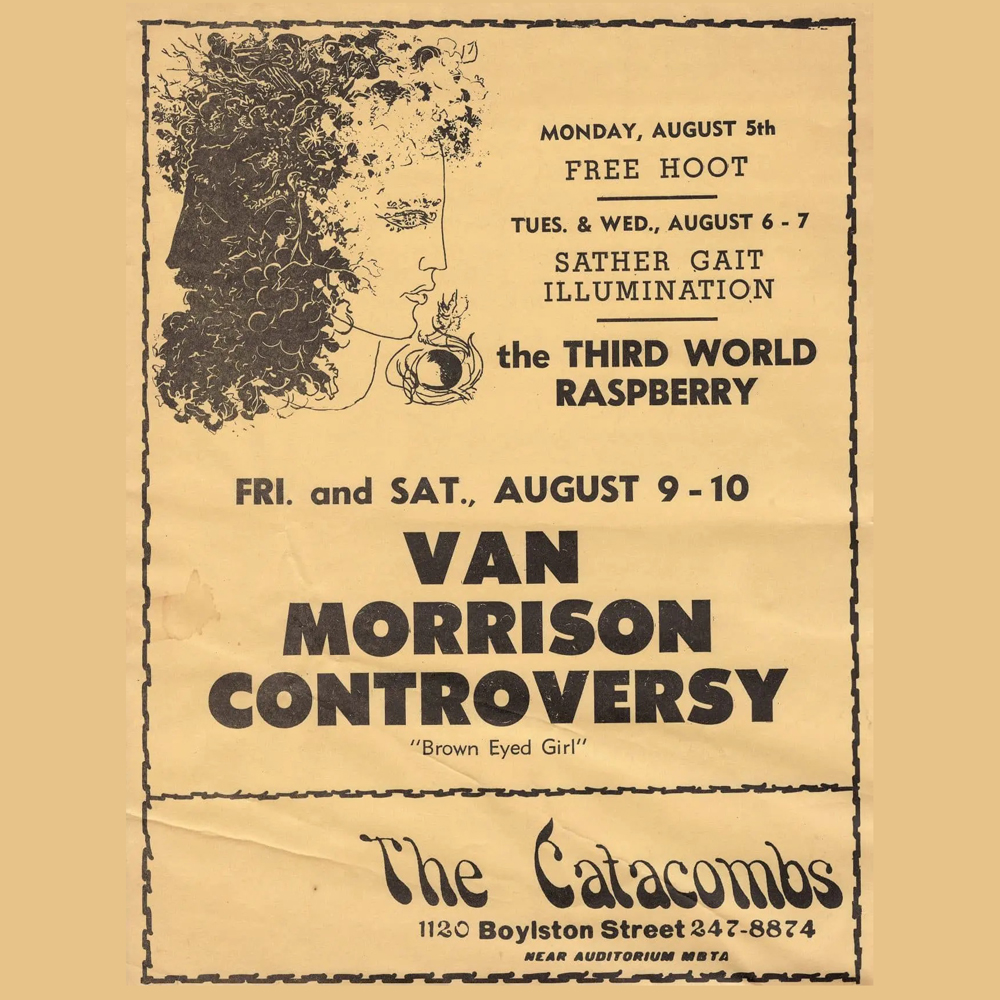

In December 1962, after being featured in the Cambridge-based bi-weekly The Broadside in September, Washington appeared at the debut Boston Folk Showcase along with the Charles River Valley Boys and von Schmidt. In 1963, Vanguard released his second LP, Jackie Washington/Vol. 2, and Washington made the first of many future appearances at the Unicorn Coffee House and The Catacombs while debuting at the New England Conservatory and the Newport Folk Festival and opening for Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band at Symphony Hall. Baez has said that Washington taught her Phil Ochs’ “There But For Fortune” that year, which became her first charting single in 1964.

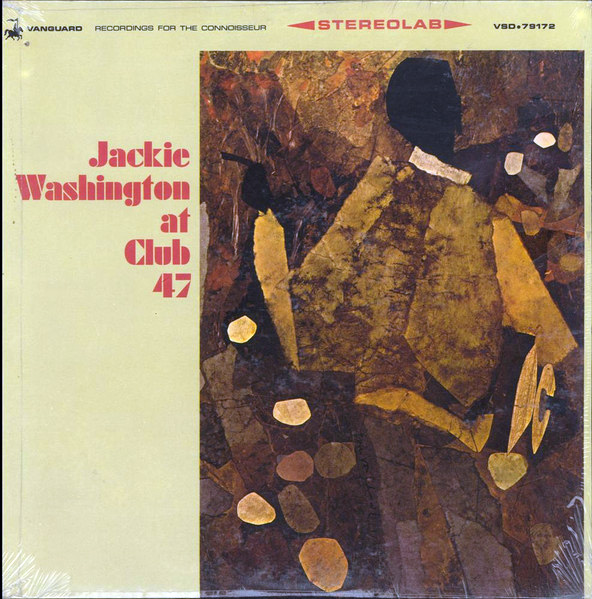

In 1965, Vanguard released the live album Jackie Washington at Club 47, which features a cover collage by von Schmidt, a renowned illustrator. An excellent example of his stage act and proof of why Washington considers himself a storyteller above all else, it includes him talking to the audience between songs to establish the context of the next tune while offering amusing personal anecdotes, revealing his lifelong love for the work of comedian Bill Cosby.

Move to New York City, Name change, Morning Song

In 1967, a year after Washington moved to Manhattan to pursue acting under the name Jack Landrón, Vanguard released Washington’s final album on the label, Morning Song, his first with a full band. To all ears, he seemed to be following Dylan’s controversial lead by “going electric” the way Dylan had done on the first side of his 1965 LP Bringing It All Back Home and at Newport that year. Featuring drummer Alvin Rogers, guitarist Mitch Greenhill of Dorchester and arranger Felix Pappalardi (who would later become co-vocalist and bassist of Mountain and appear on their 1970 hit “Mississippi Queen”), the album included only Washington’s originals, highlighting his remarkable development as a songwriter.

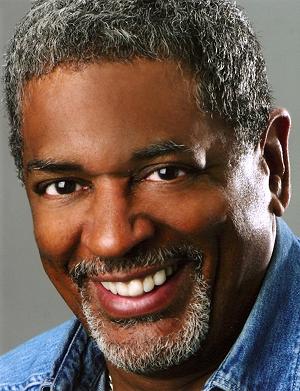

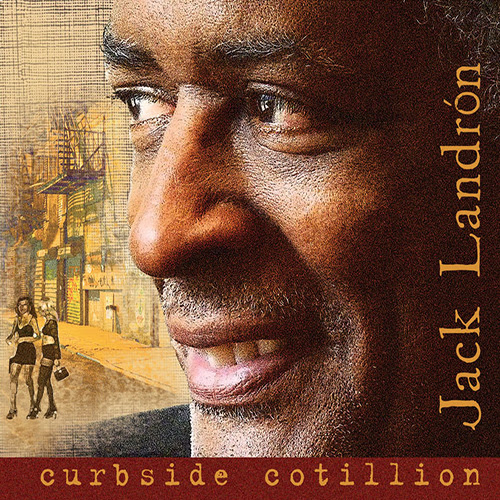

Move to Los Angeles, Curbside Cotillion, For the Love of the Music

In 2009, Washington relocated to Los Angeles, where he lives today. In 2012 Kingswood Records released his first album in 45 years, Curbside Cotillion, under the name Jack Landrón. Recorded with a full band, the 12-track LP also includes Washington’s originals only and features a relaxed, cabaret-like vibe chock full of Latin rhythms. In February 2013, Washington played at Club Passim, formerly Club 47, and appeared in the documentary For the Love of the Music: the Club 47 Folk Revival along with Baez, Tom Rush, Taj Mahal and Maria Muldaur.

Comments on legacy

Asked in a 2013 interview with The Boston Globe about his musical legacy more than 60 years after his debut, Washington laughed. “I am an antique in that I don’t know a lot of things,” he said. “Somebody showed me Wikipedia and Googled me, and there’s a whole lot of material about me that I didn’t know was there. I didn’t, and I don’t to this day, know how it gets there or who puts it there.”

(by D.S. Monahan)