Fort Apache Studios

Every band needs a place to call home. Chances are, if you were gigging about Boston in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Fort Apache Studios was yours.

The list of acts that logged time at the Fort is lengthy, beginning first with local rock heroes and later some of the biggest acts of the alt-rock era. Radiohead recorded their first two records the studio’s Camp Street location, Hole cut their 1994 album Live Through This at the Fort and Weezer assembled there in 1996 for their lovesick masterpiece Pinkerton.

It’s an impressive resume, but even more interesting than the work that came out of Fort Apache is the DIY ethic that drove its operation. The studio that helped define the sound of the city and much of alternative rock in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s came to fruition in much the same way many of the bands that recorded there did. It was an experiment, something its creators did for no other reason than because they could. “We just wanted to have a studio and we did it,” said Sean Slade, one of the studio’s co-founders, in a 2016 interview with Consequence of Sound.

Opening, “a never-ending blank canvas”

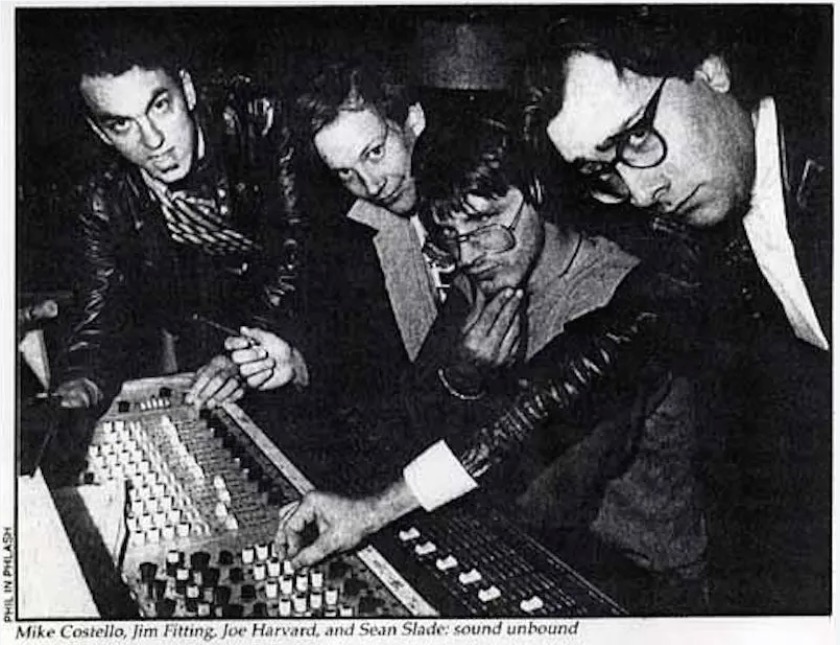

Slade’s words more or less define the Fort Apache aesthetic. He, Paul Kolderie, Jim Fitting and the late Joe Harvard didn’t have any grand scheme in place when they first set up shop in Roxbury in 1986, and that was in large part the very point. The foursome treated the studio like a never-ending blank canvas; every band that walked through the door offered an opportunity to play around and try something brand new. For a group of guys in their 20s unsure of where to go or what to do post-college, it was a challenge worth diving into – happily.

Yale beginings, The Sex Execs

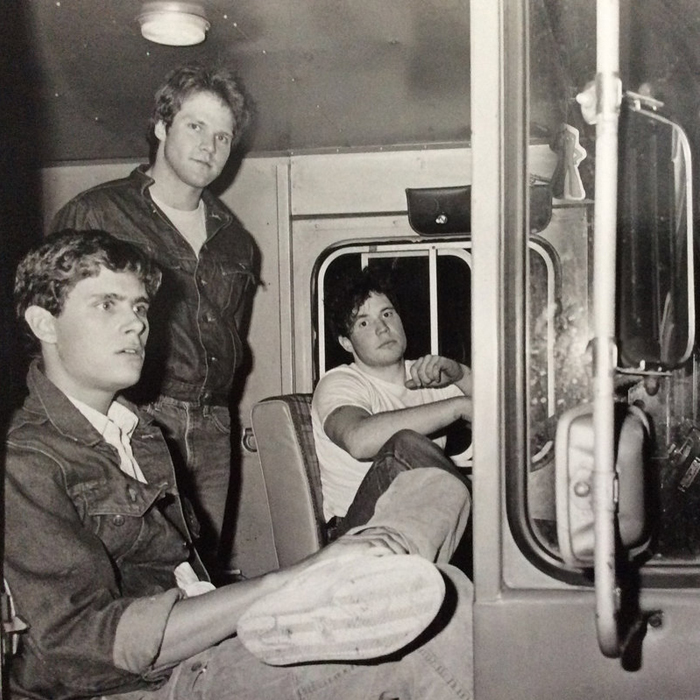

Slade, Kolderie and Fitting met at Yale, where they were misfits in the otherwise white-collar Ivy League crowd. The three shared the same dorm – “They might have done it on purpose,” Slade once said of the school’s housing overlords – and eventually formed their own band, The Sex Execs. The group was a somewhat overlooked product of the early ‘80s New England music scene, but managed a few releases nonetheless before breaking up. The three continued to make music together, but not as a formal unit. “When the band broke up, we kind of felt like that was the next step, to build a studio,” Kolderie told Consequence of Sound.

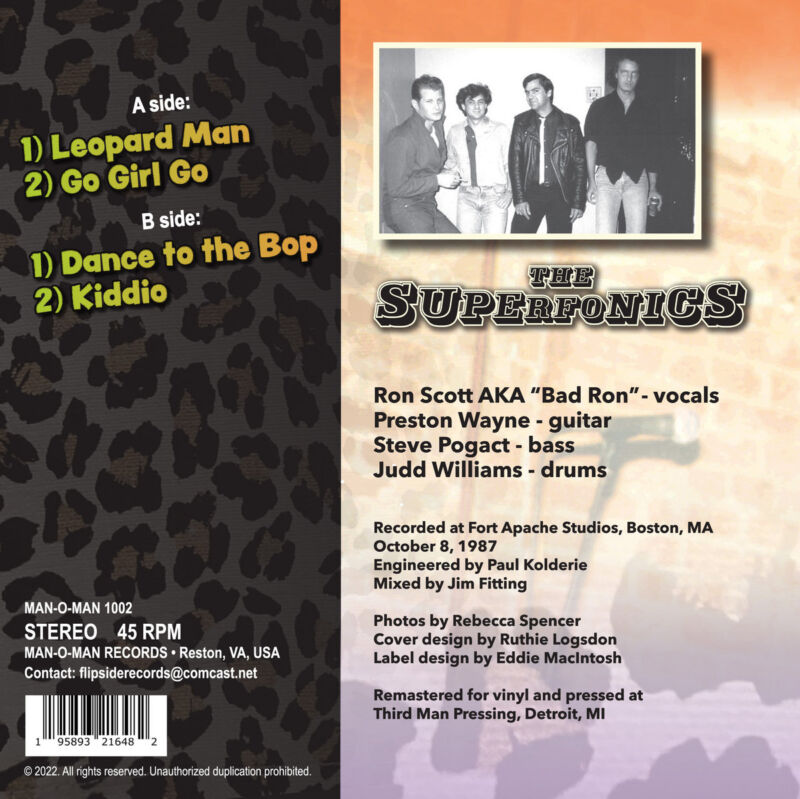

First recordings

The guys moved to a house in Dorchester, where they took their earliest stabs at studio production on a four-track. One of the first bands they recorded was The Bones, through which they met Joe Harvard. A graduate of his namesake university, Harvard was also dabbling in production at the time so it made perfect sense for him to join forces with his Yale counterparts. “We knew each other from bashing around,” Harvard told Consequence of Sound. “I realized from watching them that ’Hey, you can do this!’”

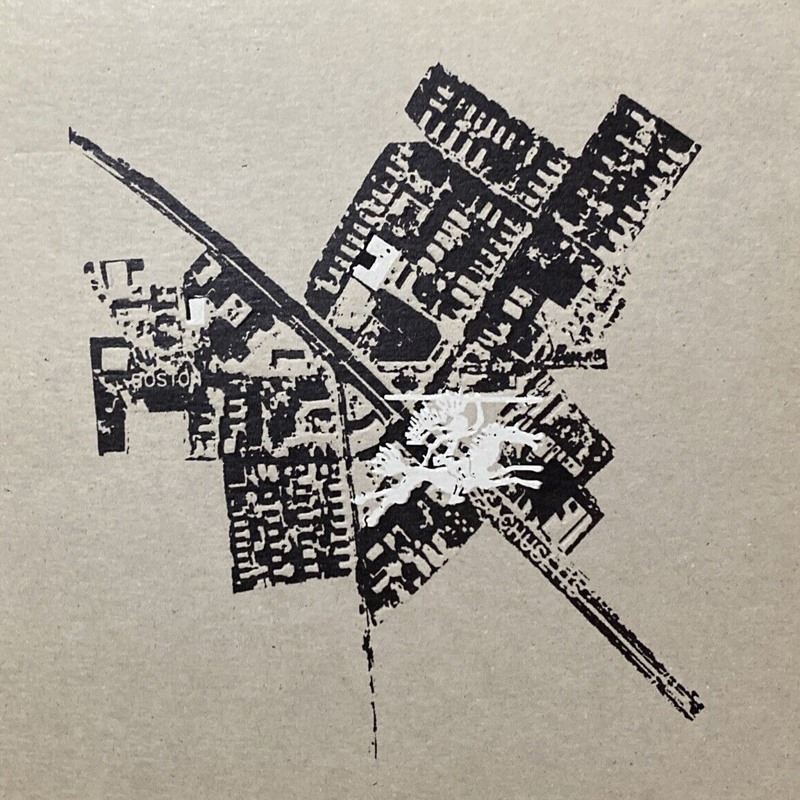

Financing, 169 Norfolk Avenue location

In fact, it was Harvard that played the biggest hand in financing Fort Apache, the name being a caustic nod to the studio’s dangerous surroundings in Roxbury at the height of the ‘80s crack epidemic. Harvard had taken to dealing weed with the expectation that he was going to start a family. That didn’t happen, but by the time he realized as much he had socked away enough money to enter into a lease on property at 169 Norfolk Avenue in Roxbury.

The building, a former commercial laundry business, occupied a full city block. A wall was put up to separate the studio from the rest of the space, and with that the shell of the studio was in place. “I think we had the idea that there could be a studio somewhere in between,” Kolderie recalled. “It could be cheap but have good recording gear. And there was a need by bands to record. There were a lot of good bands with good songs and they needed demo tapes. We just saw an opportunity there.”

Studio set up

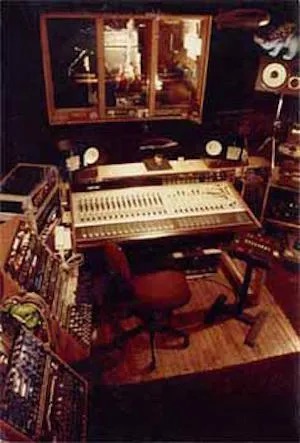

In late 1985, Harvard drove out to Chicago to buy a used console. Dana Colley, who would go on to play saxophone in Morphine, supplied the guys with ample amounts of shag carpeting secured through various construction jobs around Boston, which was put up on the walls to absorb sound. Glass was put up to separate the control room from the musicians and equipment, and that more or less covers the original studio set up. “The plan was, ‘Get a control room, get a playing room, get the wiring right, get a console, and then just start recording,’” Slade said.

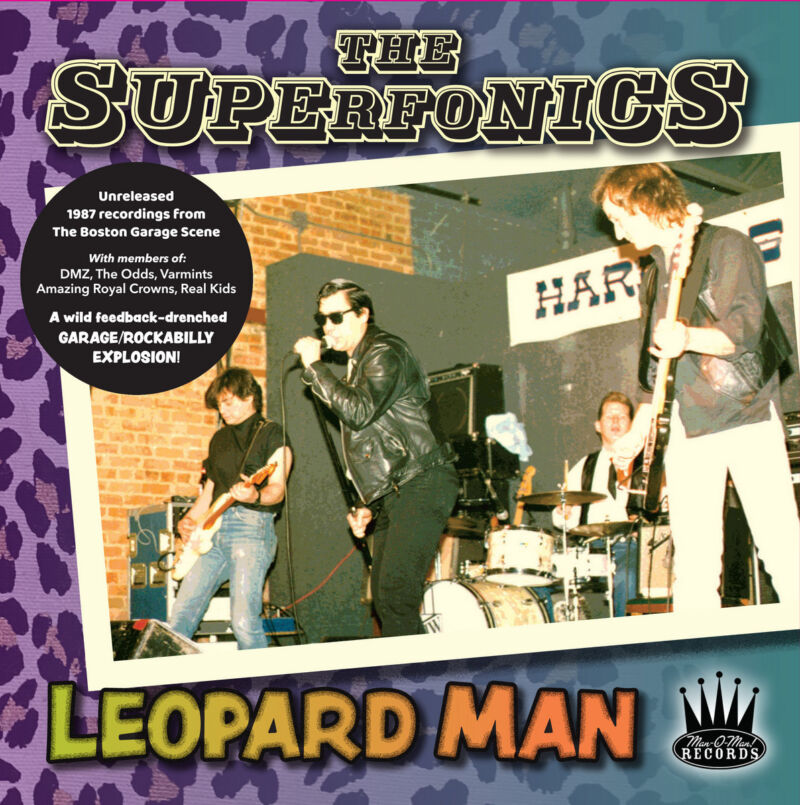

Grueling schedule, Notable early recordings

And record they did – pretty much non-stop. Kolderie recalls working as many as 54 straight days in the studio in its earliest days of operation, a testament both to the work ethic of its operators and the abundance of bands in Boston in need of an affordable recording space.

According to Harvard, the studio’s first paid job was a three-song demo by The Connells, a Raleigh, North Carolina-based band that had a few songs in minor rotation on MTV. The snowball hurdled downhill from there, as the studio produced records by bands including Big Dipper, Volcano Suns, The Lemonheads, Buffalo Tom, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Moving Targets, Miracle Legion and others. “Those guys, that team, they worked around the clock,” Bosstones frontman Dicky Barrett said. “They got obsessed with working on whatever was in front of them. If those tapes were running, they were there. They didn’t want to stop, the same way we didn’t want to stop.”

“We didn’t want to be all things for all people,” said Slade. “We only wanted to record bands. People said, ‘You’re crazy. You’ll never get any business.’ But we got tons of business because we got every single rock band in town.”

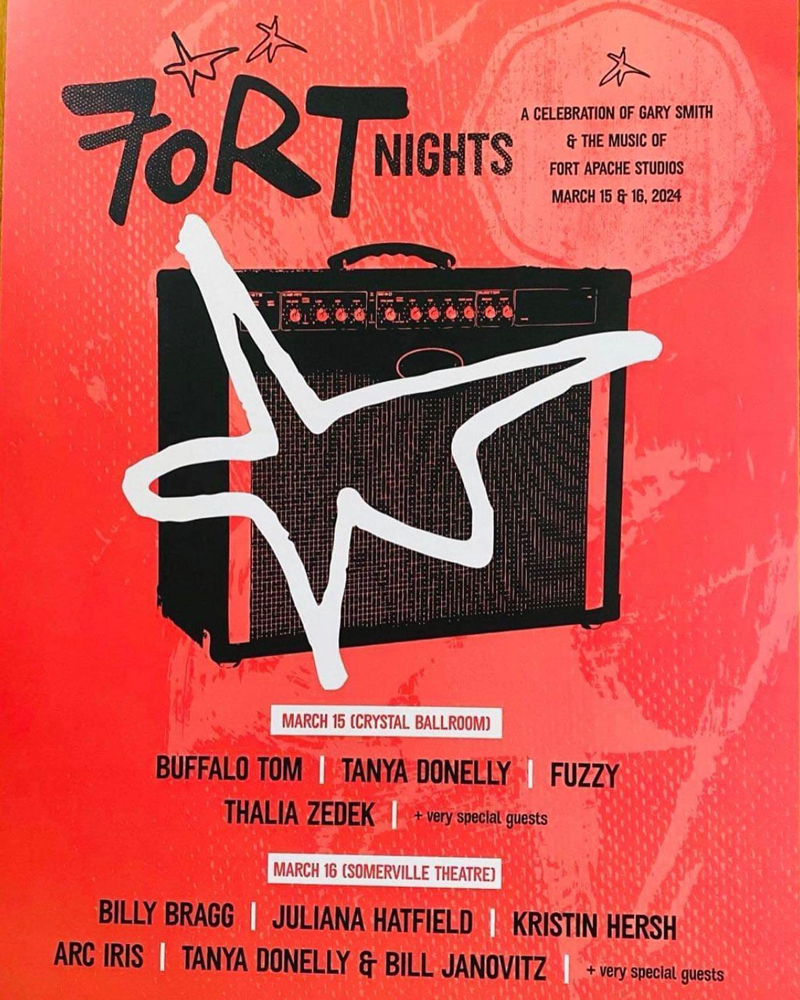

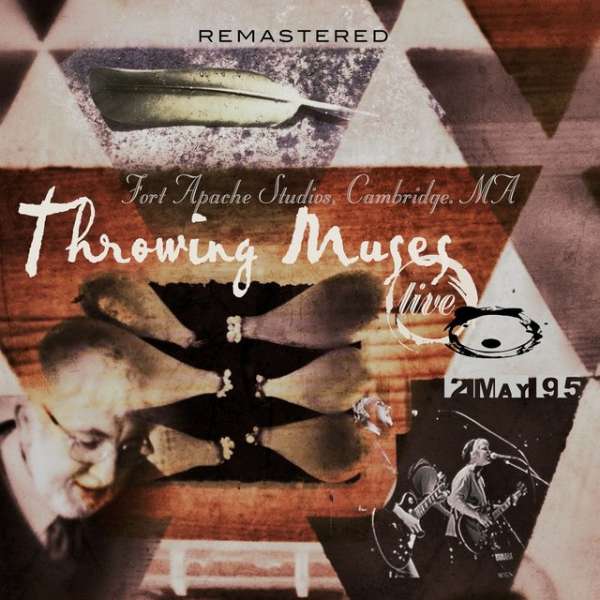

Gary Smith, Throwing Muses, Pixies, The Breeders

The original four got Fort Apache moving at a fast clip, but bringing Gary Smith into the fold took the studio’s operations to the next level. He managed acts including Juliana Hatfield and Throwing Muses, both of whom recorded at the Fort’s Norfolk Ave. location. In a major coup, he brought Pixies into the studio in 1986 to record their debut EP, Come on Pilgrim. “We drank a lot of Jolt Cola and I remember spending the night on the floor of the control room,’ said Pixies’ bassist Kim Deal, who went on to record again at the Fort with The Breeders. “It was non-stop. We barely slept the whole weekend.”

Smith eventually took on the role of managing the studio and under his watch Fort Apache became a more legitimate operation. “We started the studio without him, but it never would have been as successful as it was without Gary,” Kolderie said. “He came in and got us organized, installed some accounting so records could be kept and taxes could be paid. He turned it into a real business.”

Relocation to Cambridge

But growing business and increased demand eventually forced the studio to expand beyond its Roxbury origins and Harvard heard through a friend about a studio space in Cambridge on Camp Street. Located above Rounder Records, the 24-track studio was the perfect space for the Fort to capitalize on the increased demand for its services. Realizing immediately that it was beyond Fort Apache’s price range, Harvard, who had since taken on the role of sole proprietor of the Fort, negotiated a price with the Camp Street studio’s then-owner, John Nagy.

“I think he wanted $300,000 and I knew it was worth it,” Harvard said. “But there was no way I was getting that kind of money together. So I told him, ‘We work our asses off. We’re hungry and we love what we do. We’ll take your beautiful thing and we’ll do something special with it.’ I got that place for $75,000.”

“Fort Apache South,” “Fort Apache North”

By 1988, there were two studios in operation. The Roxbury location, known locally as Fort Apache South, continued to record demos and records for bands on a smaller budget. Camp Street became known as Fort Apache North, a spot that welcomed in bigger acts with more money to play with. “It was a great room with these checkerboard tiles, and the recording room was a nice, big room with a little isolation booth on the side,” said bassist Lou Barlow, who recorded at both spots with Sebadoh and Dinosaur Jr., of the Camp Street location. “It was a big studio, but it was also kind of compact. The control room was really great. They had a big board, big speakers on each side and a big window. The setup was extremely logical.”

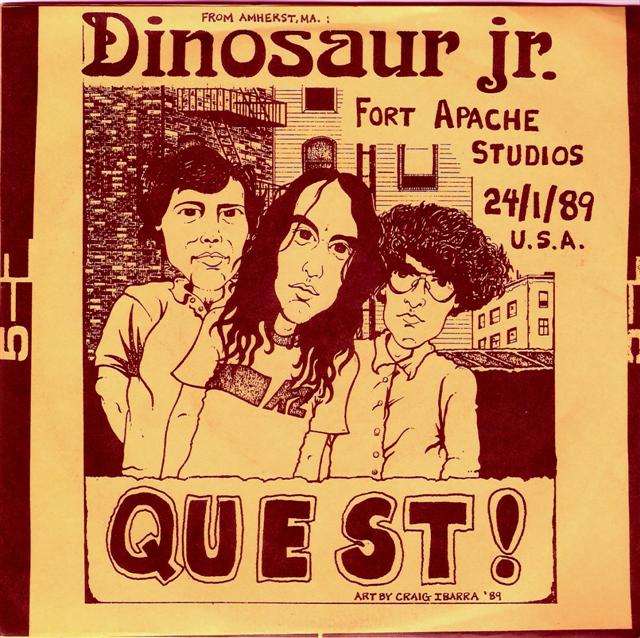

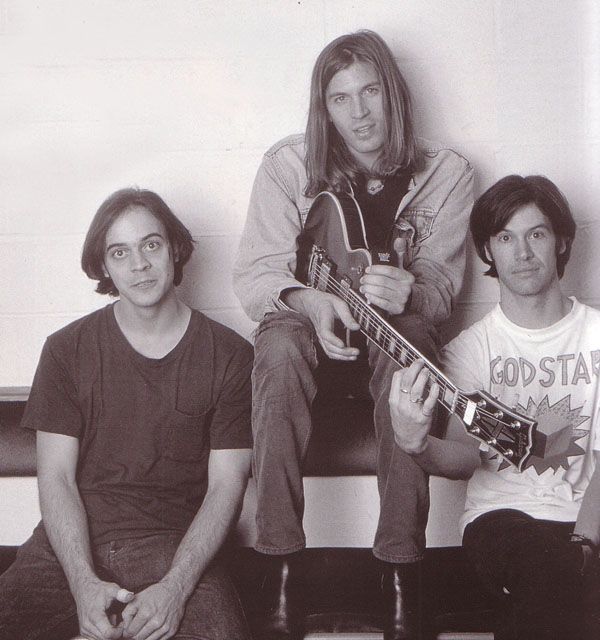

Dinosaur Jr.’s Bug

Barlow was with Dinosaur Jr. when the trio recorded their widely-influential third release, Bug, at the new Camp Street digs. The recording got off to a rocky start, between both the members of the band and the band and the Fort Apache crew. The common denominator was frontman J Mascis, who at the time had assumed an almost dictatorial control of the group’s music. “J was sort of left alone to do all of his stuff,” Barlow said. “[Drummer] Murph and I went in and did our parts and then just got the fuck out of J’s way. At that point, he just wasn’t happy, so we stayed clear of him.”

“I would say when Dinosaur Jr. first came in, J refused to talk to us,” Slade said. “Whenever we made a suggestion like, ‘What if we put the amplifier over here?,’ he’d say, ‘I don’t know.’ But we had a breakthrough the next day when I turned around and said, ‘What’s all this ‘I don’t know’ shit?’ He started to laugh, then we became friends.”

Label Attention, Adding Engineers, Alt-Rock/Grunge Boom

Those issues aside, Bug became an underground hit and Slade credited the record with further building the studios reputation. “Throwing Muses and Dinosaur Jr. put us on the map for major labels,” he said. “They showed we were a real 24-track studio that could make major-label records.” The studio also brought additional engineers into the fold, including Tim O’Heir and Lou Girodano, both of whom would go on to establish themselves as reputable producers in their own right.

Things at Fort Apache remained busy and by the early ‘90s the studio had positioned itself perfectly to reap the rewards of the alt-rock/grunge boom. The guys wooed Radiohead on the strength of their work with Pixies and Miracle Legion and the band’s 1993 debut, Pablo Honey, was mixed at Camp Street. “Fort Apache had this thing going for it,” said Bill Janovitz of Buffalo Tom. “Radiohead came, Hole came, Uncle Tupelo came, Weezer came. It became this place that bands from around the world came to.”

Further Expansion, This Is Fort Apache Compilation

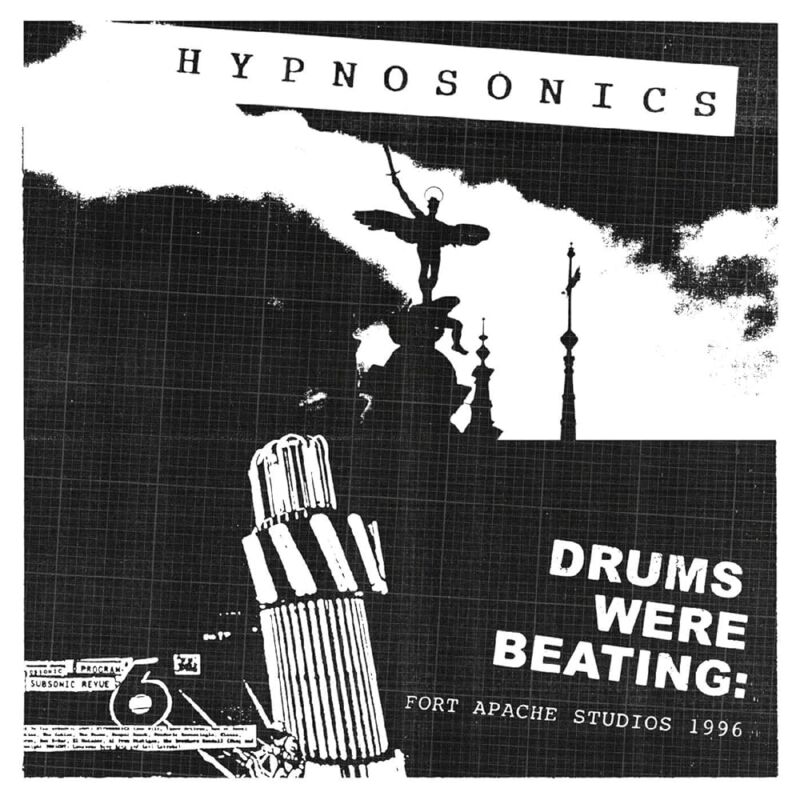

In the mid-‘90s, Smith, who in 1991 bought Fort Apache outright from Harvard alongside Billy Bragg, worked on expanding the studio’s professional reach even further. He purchased studio space on Edmunds Street, not far from the Camp Street location, where the studio recorded live performances for radio stations including WBCN and WFNX.

A collection of those performances by the likes of David Bowie, Goo Goo Dolls, The Lemonheads, Throwing Muses, Radiohead, Belly, Come and others was released on the compilation This is Fort Apache in 1995. But, as Slade recalled, the Edmunds Street venture in retrospect marked the beginning of the end of the studio’s “classic” era. “I personally never liked that place,” he told Consequence of Sound.

Relocation to Vermont, Rise of the Internet, ProTools

By 2000, Smith moved Fort Apache’s operations out of Cambridge to his home in Vermont to little success. The Roxbury studio had long since run its course, and work on Edmunds Street had also been shuttered. Efforts to give the Camp Street studio a second life also failed to bring things back to Fort Apache’s heyday.

Kolderie ran the spot as Camp Street Studios from 2002 to 2010, but drastic changes in the recording industry brought on by the Internet and technological advancements such as ProTools made keeping the business afloat difficult. “You used to get $200,000 to record a band, then it was $20,000,” he said. “Now it’s $2,000, y’know? I was maintaining a place that had hundreds of thousands of dollars of vintage equipment and instruments … and people just stopped caring.”

Post-Fort Apache activity

Kolderie continues to record from his home in New York while Slade has found a second career in academia, teaching music production and engineering at Berklee College of Music, a “godsend” career move, as he puts it. “I really needed a regular job,” he said. “The whole thing of being a freelancer, I was just too old to do that kind of stuff.” Harvard became something of a cultural guru in Asbury Park, New Jersey, where he ran the gARTen, an outdoor trash art collection. Pat Schiavino, a city artist and developer, hired Harvard to engineer sound at the Wonder Bar when he owned the Ocean Avenue nightclub in the mid-aughts. He died of cancer in March of 2019 at the age of 60.

“Joe is one of our original artists, musicians, bohemian people that came into Asbury Park when people were just starting to move here,” Pat Schiavino, who worked with Harvard when the former owned the Wonder Bar in Asbury Park, told the Asbury Park Press following Harvard’s death. “He brought a tremendous talent and creative energy to the city and had a real positive effect on all of us and everything that’s happened, as recently as his garden on Cookman.”

Here in Boston, Harvard and the rest of the Fort Apache crew continue to be remembered for the hand they had in helping put the city’s rock scene on the global map. “I don’t think Fort Apache’s impact can be overstated by any of us,” Buffalo Tom’s Janovitz said.

(by Ryan Bray)