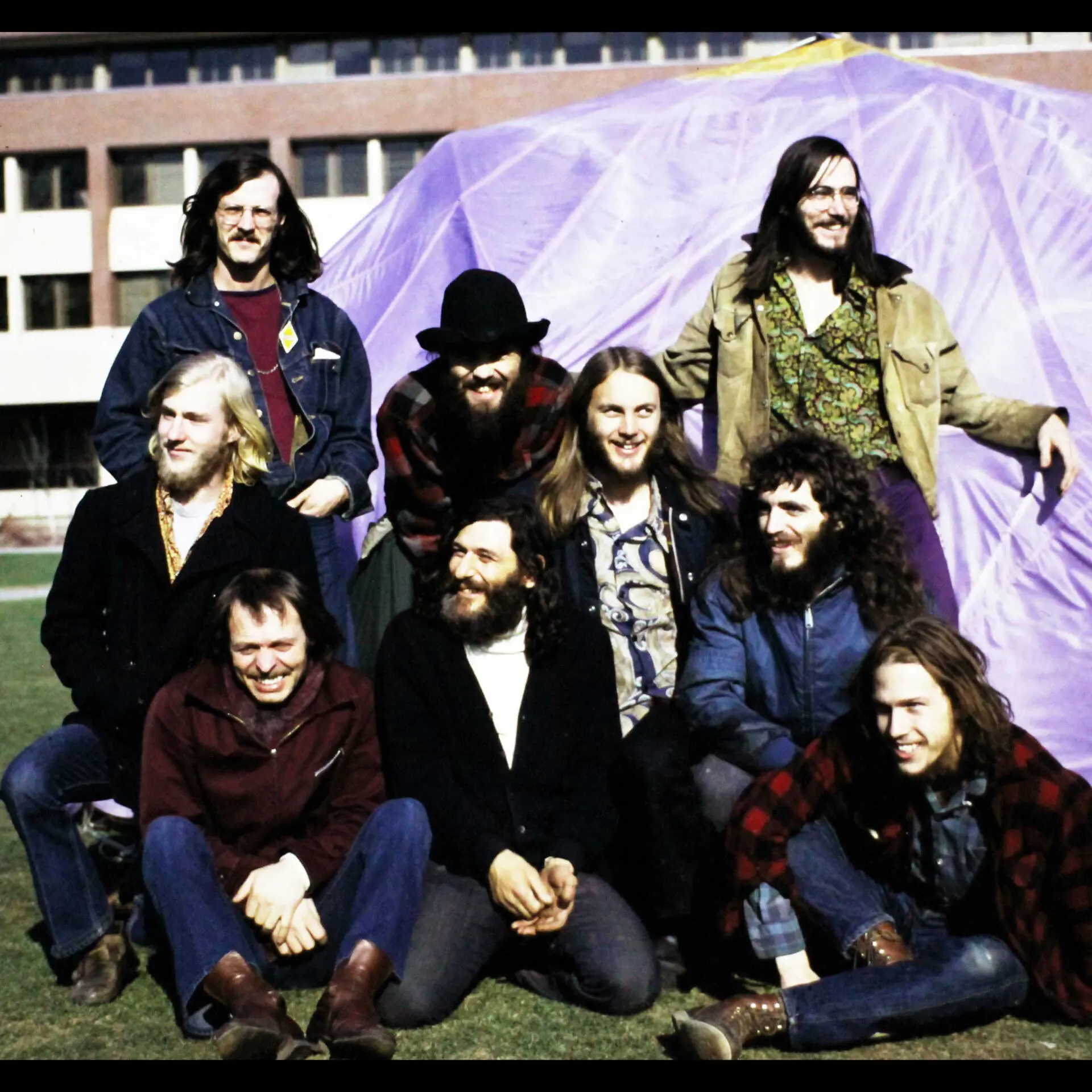

Far Cry

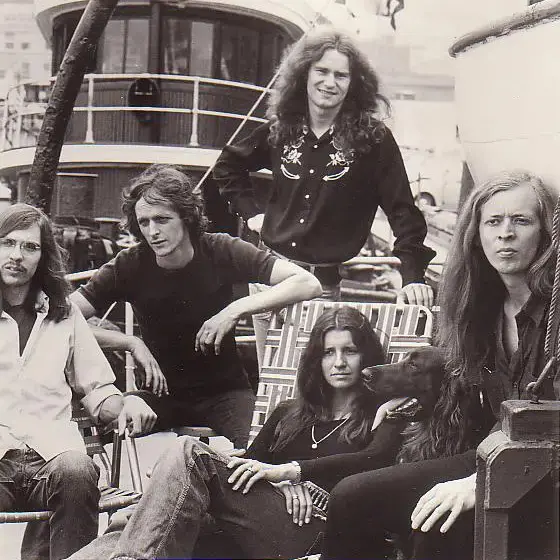

In the summer of 1968, in South Hampton, New York, Boston-based group Far Cry became the house band at Long Island’s newest, biggest dance club, The Alley, a converted bowling alley. For about six weeks, they played for a young audience, some hip, some straight. Being a spacey blues-rock band that would sometimes play only three songs in an hour-long set, however, the fit was not what anyone would consider “good.”

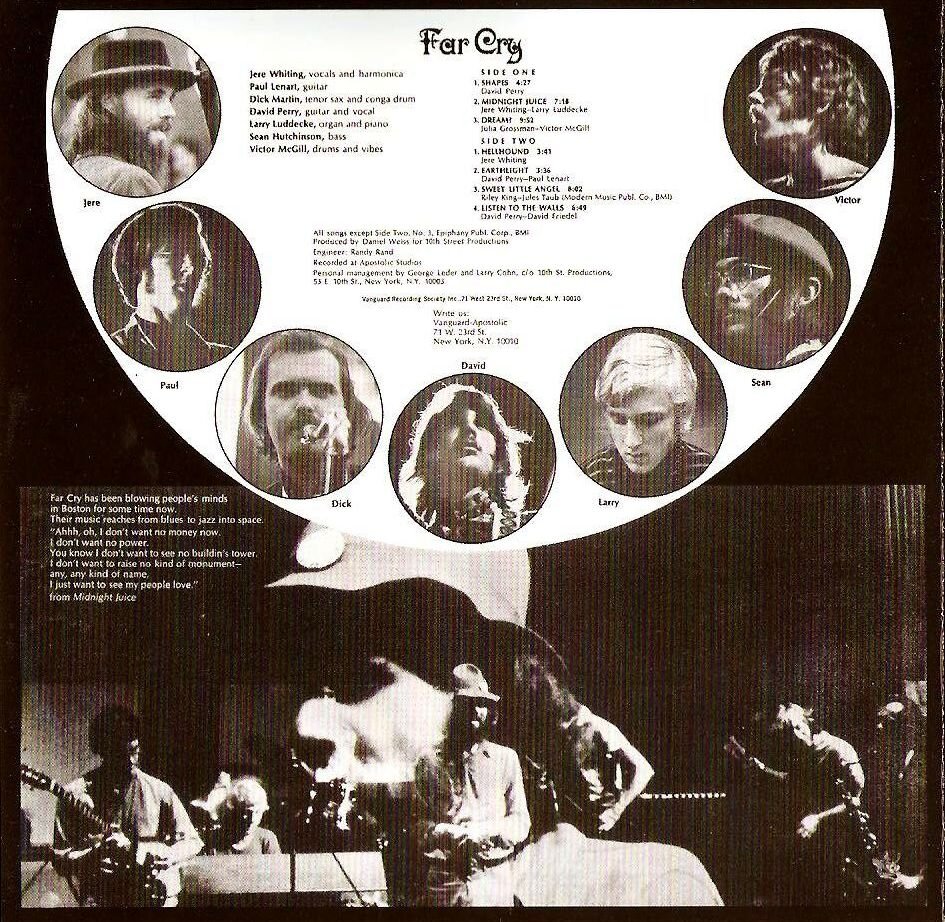

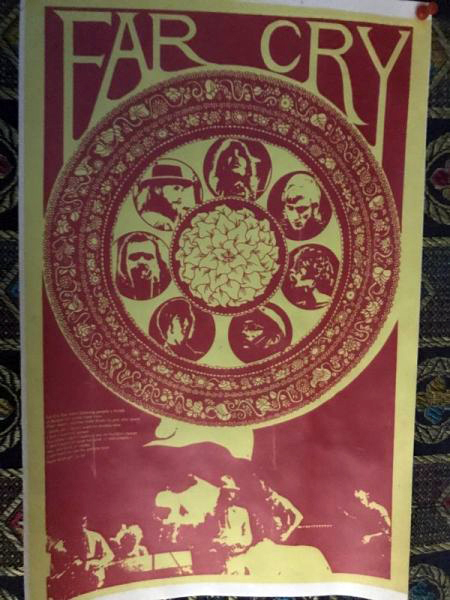

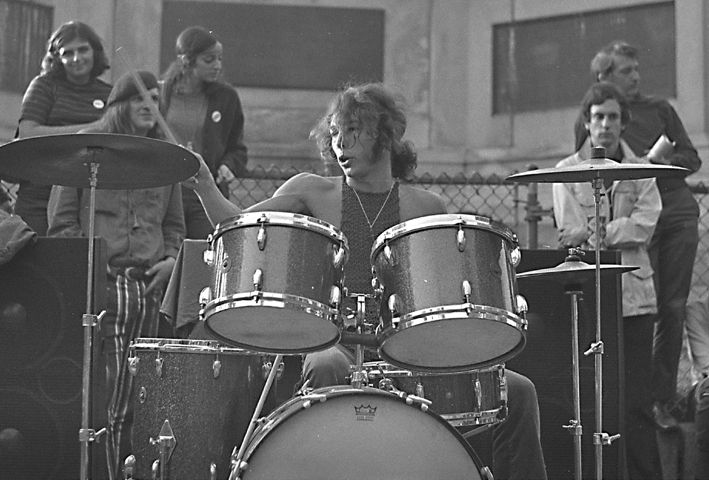

The band was all over the map in terms of influences, from jazzy sax and drumming to rock tunes by bassist Sean Hutchinson and keyboardist Larry Luddecke, who had gone to high school together. Lead singer Jere Whiting and guitarist Paul Lenart came from a more traditional blues background, with people calling the former a mixture of Howlin’ Wolf and Captain Beefheart. It was new and free-form and shows varied from night to night – sometimes brilliantly, other times disjointedly – but it seemed to be working. They had a substantial following at the Electric Circus and played at Washington Square and outdoors at Lincoln Center.

DEBUT ALBUM, RETURN TO BOSTON

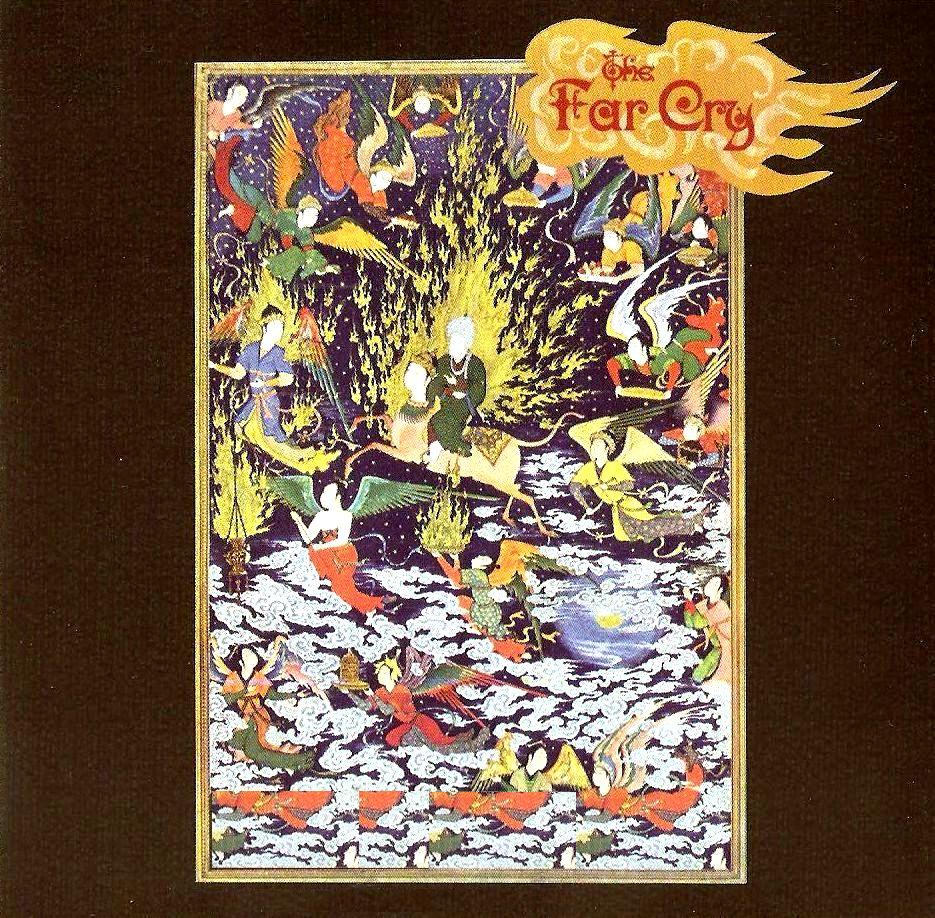

The managers of The Alley believed in the group so strongly that they helped land them a deal with newly established Vanguard/Apostolic, a Vanguard offshoot that wanted to jump on the rock bandwagon, having previously been (just like Vanguard) a rootsy Americana label. Far Cry went to Apostolic Studios on East 10th Street. for about 10 days and recorded their sole album, Far Cry. Then they packed up and headed back to Boston, some to school, some to work. The packaging and promo was left to the label and the managers.

Guitarist David Perry returned to Harvard while Lenart and Hutchinson went back to Tufts. Luddecke was just starting at Harvard and saxophonist Dick Martin was a graduate student there. Whiting was the son of a Harvard professor. The rhythm section was Victor McGill on traps and David Earl Johnson on congas and percussion. In between all the colleges in New England, the festivals and the protests going on, weekend work was plentiful.

LOYAL LOCAL FOLLOWING, GREENVILLE FARM

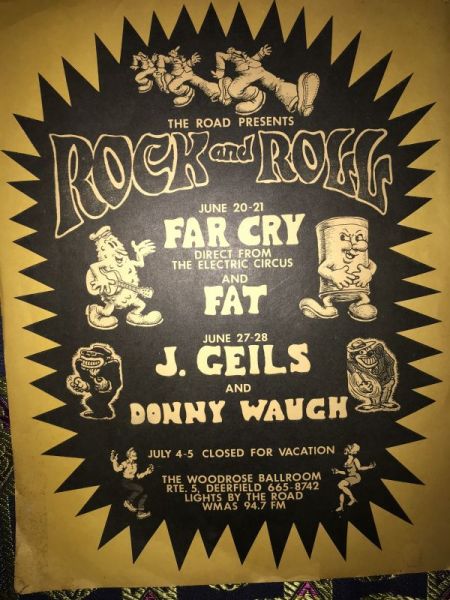

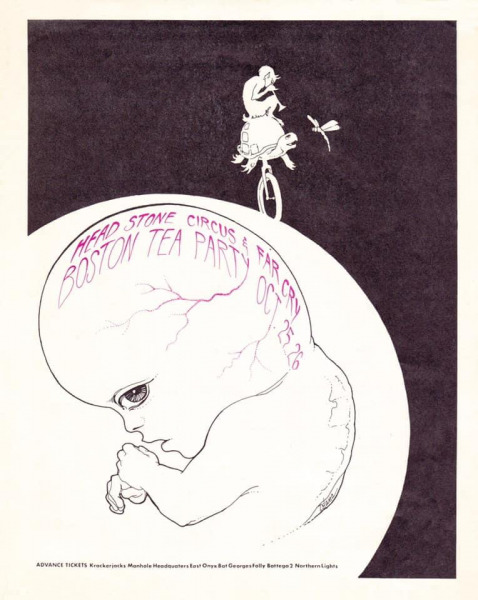

The band developed a loyal following in Boston and Cambridge from gigging at popular clubs and the free Sunday concerts on the Cambridge Common. The other regular acts there were more representative of the emerging “Bosstown Sound” like Ultimate Spinach, The Beacon Street Union and Ill Wind and 17-year-old Jonathan Richman often played solo in between set changes. Throw in out-of-town bands who might have played at The Boston Tea Party the night before, like the then-unknown Allman Brothers, and each week was a very solid show.

During the school year, the students in the band had dorms or apartments in Cambridge. The others ventured up to Greenville, New Hampshire and found half of a huge old farmhouse to call home. During the summer of ’69. the rest of the band moved up to the farm/commune, where they jammed endlessly while leaving on weekends to play gigs from in upstate New York, Connecticut or in New York City.

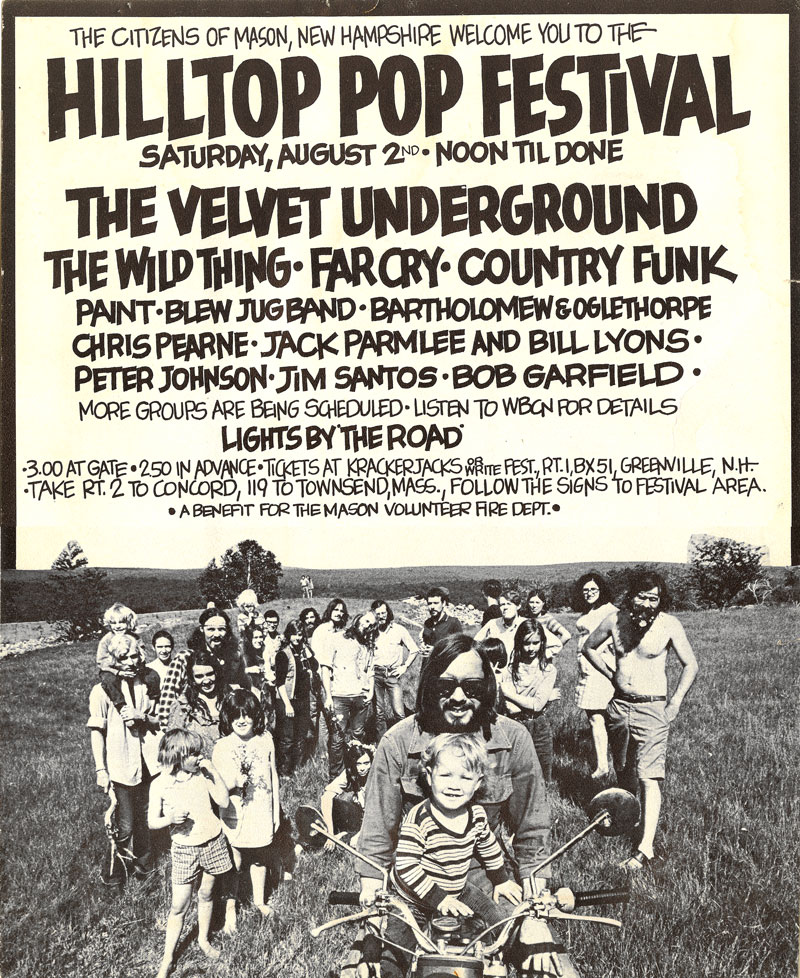

HILLTOP POP, ARTHUR BROWN GIG

In early August 1969, two weeks before Woodstock, neighboring Mason, New Hampshire, threw its own festival, Hilltop Pop, headlined by Far Cry The Velvet Underground, Country Funk and The Wild Things. At the last minute, Van Morrison signed on to complete the bill. It was a great gig on a beautiful day with an infamous after-party at the farm (where Morrison stalked around for most of the night).

After a break when some of the band went to Woodstock, the band resumed their routine. One day the band got a call from the Boston Tea Party saying that Arthur Brown was booked that night but he had been tripping for three days and fired his whole band. Would Far Cry come down and back him up? Sure, why not? The band loaded up the rusty old van and rumbled down to Boston. They knew “Fire,” Brown’s biggest hit, and opened with that before launching into a blues number before Brown invited the entire crowd up on stage. Ten minutes later, the show was over.

“BIG BREAK” FLOP, DISBANDING

When the students went back to school in September, the farm was more than the others needed so they found a smaller house with a barn over in Mason. It was unheated save for a wood stove, so rehearsing was difficult. Gigs were still there but the music was stagnating. What they thought was going to be their “big break” came in November 1969: a slot at the Fillmore East on “new music Tuesday.” They rumbled down to New York with their gear and best stage clothes. After a sound check and some nervous hours of down time, it was show time. The house was pretty empty but a bunch of big cheeses from the labels were supposed to be there. It was not a particularly inspired night musically, especially after Hutchinson broke a bass string in the fourth song. That never happens, so he didn’t have a spare. Far Cry’s manager managed to rent/bribe a bass from the next act after a plea to just borrow it was turned down. The show went on but a good portion of the band’s allotted time had been lost on bass negotiations.

Thus, the big break was essentially a big flop. The big cheeses had not shown up so the band rumbled back to the farm, and not in a positive frame of mind. In the winter of ’69, there were still some college gigs, long drives to Syracuse through blizzards (in a van with dodgy heat at best), then home to weekend rehearsals in a freezing-cold barn, no matter how hard the wood stove was working. Those still living in town had started playing gigs with other local musicians, so momentum was rapidly dissipating and by spring it was clear that the end was near. The band members still got along fine but the weekend rehearsals had stopped and there was no light at the end of the tunnel.

In June of 1970, two years after that first gig at the Alley Discotheque, Far Cry chose to disband; the decision was amicable. Some are gone, some are off the grid and some are still in touch (“band chicks” and “old ladies,” too. Lenart and Luddecke are still playing and writing music together over 50 years later.