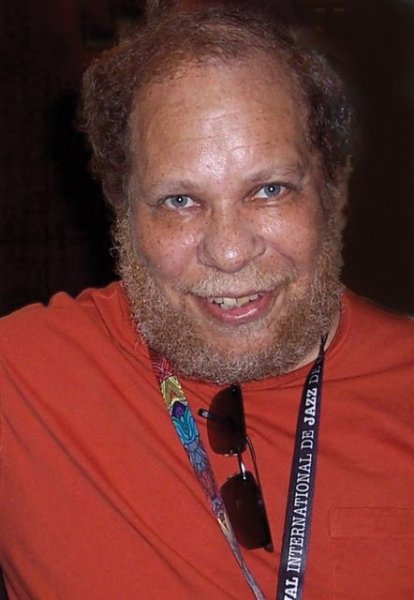

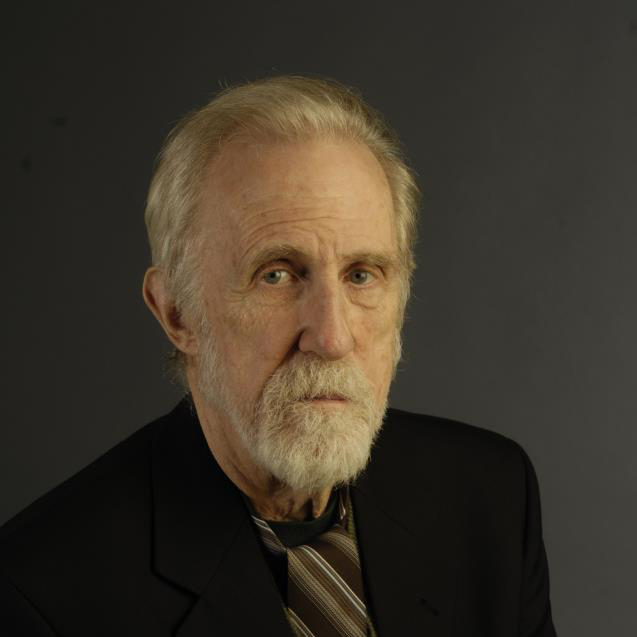

Eric Jackson

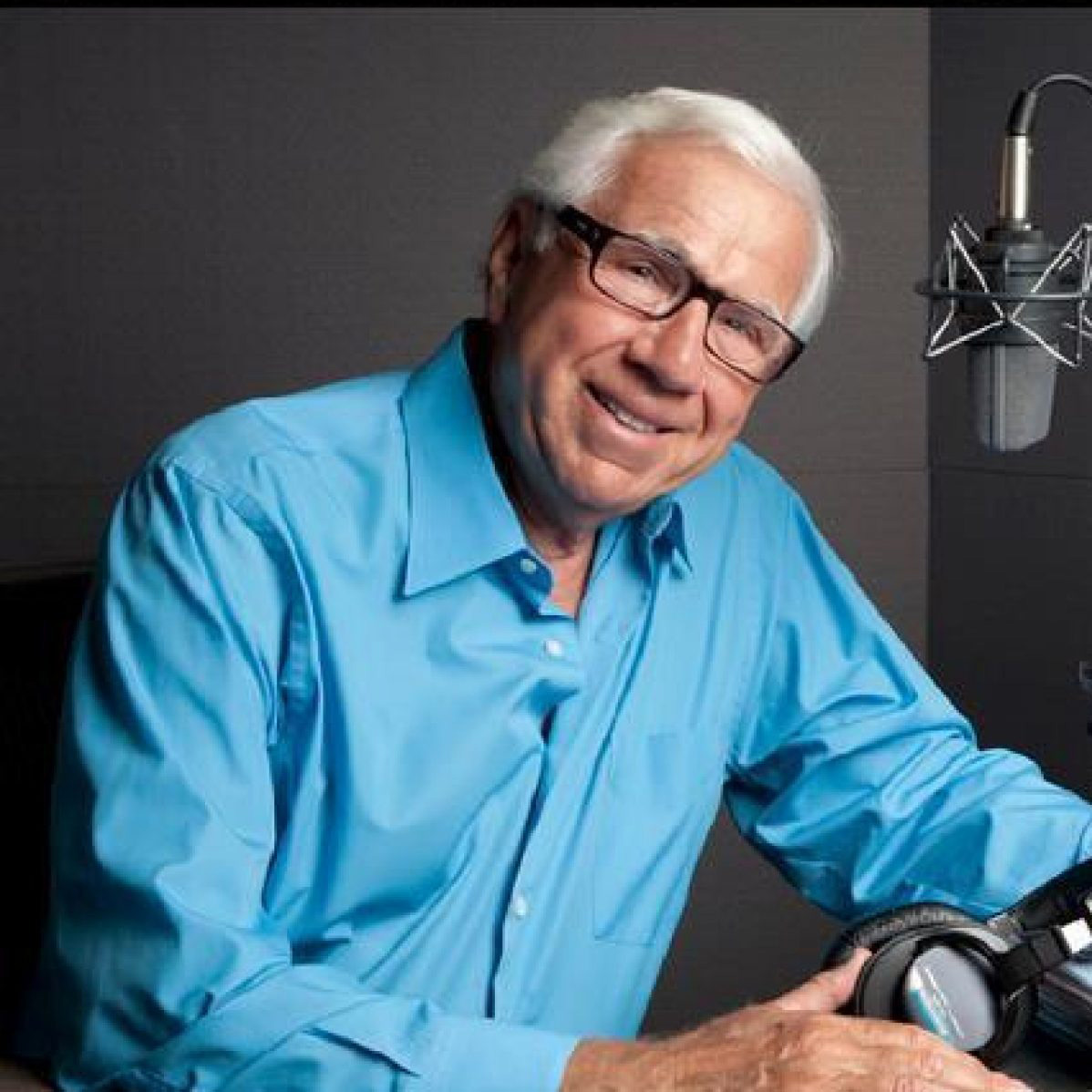

With an encyclopedic knowledge of jazz akin to Ron Della Chiesa‘s of classical and Dick Pleasants‘ of folk, Eric Jackson hosted Boston radio’s signature jazz program for over four decades and manned the city’s airwaves for more than five. And his expertise on everything from early jazz, bebop and hard bop to smooth jazz, fusion and avant-garde – combined with his deep understanding of the broader history of African-American music – earned him the nickname by which he was and continues to be known: “The Dean of Boston Jazz Radio.”

But it wasn’t just the quality of his programming that put Jackson at the front of the pack in his chosen profession, both locally and nationally. Other elements were the calmness in his voice, his cool-headed delivery and his utter absence of self-promotion, both on and off the air. “He’s always, absolutely in service to the music he plays,” said former WBUR deejay and WBZ producer Steve Elman in 2011. “In a business driven by ego, he seems to be selfless. And that warm, genial presence is something special and rare, especially in a world of media that never seems to stop shouting.”

Jackson played songs from thousands of albums over the decades, referring to every show he hosted as “a musical adventure,” and at times he improvised his selections, much like the artists whose records he spun. He introduced acts at events including the Newport Jazz Festival and annual John Coltrane Memorial Concert in Boston and interviewed some 3,000 musicians on the air, among them Dizzy Gillespie, Ornette Coleman, Wynton Marsalis, Danilo Pérez, Abdullah Ibrahim and Ran Blake. In 2011, Jackson cited Cecil Taylor and Sun Ra as his favorite artists, though he rarely played their music on his programs, he said, because their audiences were too narrow. “People who like the music aren’t as vocal,” he told Jon Garelick of The Boston Phoenix, “whereas if I put on Cecil Taylor, I guarantee people are going to call up and complain.”

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Jackson was born on January 31, 1951 in Providence, Rhode Island but was raised in Camden, New Jersey since the electronics company for which his father worked, RCA, was headquartered there. In 1947, before moving his family to Camden, the elder Jackson became the first Black radio personality in New England, working as a jazz deejay at a Providence station until 1950. A huge jazz fan, he was also an amateur singer who once won first place in a talent show in which future jazz vocal great Billy Eckstine finished second.

Like many in his generation, Jackson gravitated toward R&B and Motown in his early teens, though his father made every effort to develop his taste for jazz. “I grew up in a household where jazz was there,” Jackson told JazzTimes in 2015. “My father had control over the music in the house and that’s what was played. I still don’t know anything about classical music because there was no classical music in my house.” Occasionally, Jackson’s father returned home in the wee hours from area clubs with musicians including trumpeter Cat Anderson and drummer Sam Woodyard of Duke Ellington’s orchestra, providing his son with a rare opportunity to chat with them. For 27 years, until his father passed away in 2009, the regular Father’s Day feature on Jackson’s Eric in the Evening show was him and his father playing and commenting on Ellington compositions.

While in high school, Jackson often listened to Philadelphia-based stations WWDB and WDAS, which had very different musical formats. “In those days, I identified music by moods and each of those stations had a very distinct sound,” he said in 2011, noting that WWDB featured famed announcer Sid Mark and his all-Sinatra program (Fridays with Frank) while WDAS leaned toward soul. Throughout his career, Jackson said that setting the right mood was a key element of his programming approach. “The show has to have a flow,” he said in 2011. “The first half-hour, the first song, those are extremely important to me.”

MOVE TO BOSTON, WTBO, WBUR

In the fall of 1968, Jackson moved to Boston to attend Boston University, planning to enroll in medical school after graduation and pursue a career in psychiatry. In early 1969, after answering a classified ad posted by BU’s WTBU-AM for an announcer – “no experience necessary,” it read – he started hosting a show on the station, playing what he called “mixed music,” meaning a blend of jazz-inflected pop and R&B that included tracks by Sly and the Family Stone, Blood, Sweat & Tears and Herbie Hancock.

Though the music he played with completely outside the realm of the rock and pop of the era, he soon became one of the WTBU’s most popular personalities and wound up doing three (sometimes four) four-hour shows per week. When he asked why he was getting so much air time, the station manager replied with a comment that Jackson never forgot: “Because I know that when you’re on the air, I get quality radio.” In 2011, Jackson told the Phoenix’s Garelik that that was the first time he ever thought, “Oh, so I’m good at this?”

In early 1970, Jackson moved to BU’s FM station, WBUR, where he hosted a show called The Grotto. Around that time, his musical interests segued from R&B to the cutting-edge jazz of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, inspired largely by the latter’s 1965 album A Love Supreme. “In my sophomore year in college, I carried that album around with me and if you invited me to your dorm room or apartment, and I was there for maybe 15 minutes, I’d say, ‘Could you put this on, please?’” Jackson told JazzTimes in 2015. “I became a jazz snob. I didn’t want to hear any other kind of music but jazz.”

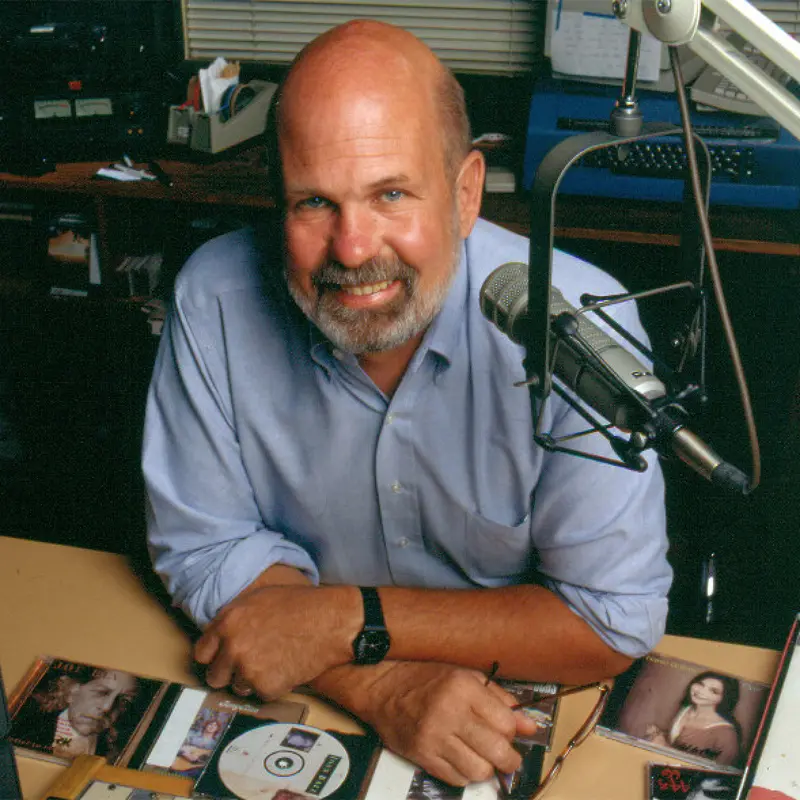

WHRB, WBCN, WGBH, ESSAYS IN BLACK MUSIC, ARTISTS IN THE NIGHT

In 1971, Jackson hosted Going East on Harvard’s WHRB and in mid-1972, after graduating from BU, he made his foray into commercial broadcasting as the host of a Sunday afternoon show on WILD while appearing at clubs as vocalist for The Phil Musra Group. Later in 1972, he moved to WBCN, where he was assigned with the task of doing “a 60% jazz show with a heavy emphasis on other forms of Black music,” he said, “but some white music, too.” During his roughly five years on the air at ‘BCN, he also produced and hosted a weekly public-affairs forum, Third World Report, and he wrote and narrated a 35-part series on African-American musical history, Essays in Black Music, that aired weekly on WGBH in 1975.

In mid-1977, after ‘BCN laid him off, Jackson began filling in occasionally for WGBH’s late-night jazz host Hayes Burnett. He joined the station’s regular lineup later that year as the host of the overnight jazz show Artists in the Night and quickly established himself as among the most knowledgeable – and one of the most popular – on-air personalities in public broadcasting anywhere in the US.

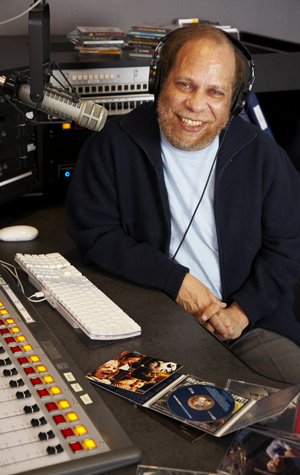

ERIC IN THE EVENING

In 1981, four years after Jackson arrived at WGBH, the station premiered what became one of its most iconic programs, Eric in the Evening, which Jackson hosted for 41 years. During most of his tenure, the show aired for five hours on four weeknights (Monday to Thursday, 7pm to midnight), but the station eventually reduced that to four hours (8pm to midnight) and, in 2012, cut it further to nine hours on weekends (Friday, Saturday, Sunday, 9pm to midnight). Jackson opened every show with Tommy Flanagan’s rendition of Horace Silver’s “Peace” (from Flanagan’s 1978 album Something Borrowed, Something Blue).

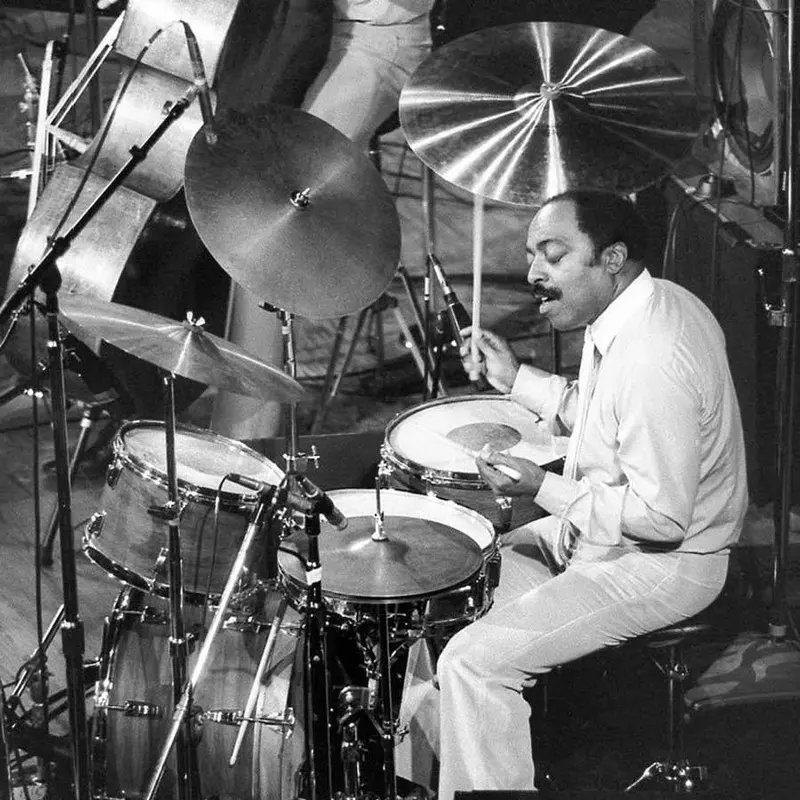

While he played a blend of old and new material – by jazz legends, up-and-comers, international stars and local artists – Jackson’s playlists reflected the jazz that caught his ear in his late teens, including Coltrane’s “classic” quartet (with McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones), Davis’ “second classic” quintet (with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams) and virtually anything Duke Ellington ever recorded. He avoided playing much of the “smooth jazz” that gained commercial traction in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s and he rarely spun anything he believed his listeners might consider too avant-garde. Jackson often hosted remote broadcasts from local venues such as Scullers Jazz Club, Regattabar and Ryles Jazz Club and live performances from the ‘GBH studios (with his late colleague Steve Schwartz).

TEACHING, LECTURING, AWARDS, ACCOLADES

In addition to his radio roles, Jackson was on the faculty at Northeastern University, where he taught a course called “The African American Experience Through Music.” He lectured at Simmons University, Longy School of Music, Wheelock College, The Leeds College of Music, New England Conservatory, the Peabody-Essex Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of African American History and provided programmed music and writing for exhibits at the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

In 2006, the Cambridge City Council named Jackson a Cultural Ambassador for the Arts and the National Jazz Journalists Association presented him with their Willis Conover-Marian McPartland Award for Excellence in Jazz Broadcasting. In 2008, Jazzweek named him Major Market Programmer of the Year; JazzBoston presented him with the Roy Haynes Award in 2011; and he received the Duke Dubois Humanitarian Award in 2012. Massachusetts College of Art and Design included Jackson in its list of the “100 most culturally influential Bostonians of the 20th century,” Berklee College of Music has recognized him for his role in “advancing careers in music” and he was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2022.

DEATH, LEGACY

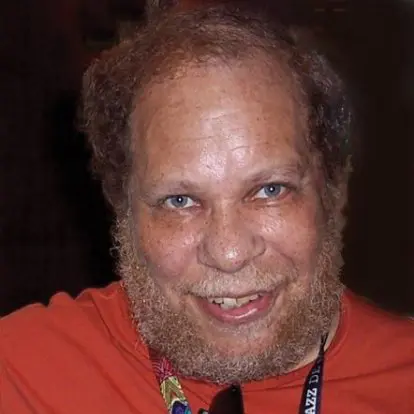

Jackson passed away on September 17, 2022, at age 72 at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital of long-term health issues and heart complications. On the night of his death, a Saturday, his Eric in the Evening fill-in Al Davis opened the show with “Peace,” as usual, followed by Coltrane’s “Dear Lord” and Aretha Franklin’s rendition of “Drown in My Own Tears.” In a written statement, WBGH General Manager Anthony Rudel called Jackson a “legend,” who always “used his warmth and intimate knowledge to connect listeners to the music.”

“Others will continue to play jazz on the radio, but no other jazz host has ever been blessed in the way that Eric Jackson was blessed,” wrote Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame board member Steve Elman in an obituary for The Jazz Fuse. “He became the Voice of Jazz in his adopted home, always the first person you wanted to have emcee a jazz concert, always the guy you wanted to interview you when you had a new recording, always the guy to tell you about a new artist who was doing something important, always the guy who put some peace into your heart when you needed it. Here in the land where jazz was born, only a handful of radio hosts have become the Voices of Jazz for their cities, and no one else has ever been a Voice of Jazz as long as Eric Jackson was.”

(by D.S. Monahan)