Dick Waterman

At first glance, “Dick Waterman: Blues Savior,” the headline of a 2020 interview with him in American Blues Scene, might seem hyperbolic. But it isn’t.

In fact, given the promotor-manager-writer-photographer-archivist’s remarkable role in helping to resurrect the careers of older blues legends like Son House and his invaluable support of younger artists like Bonnie Raitt – plus his extraordinary knack for capturing a musician’s spirit on paper and in pictures – the messianic reference is as accurate as it is clever. And the Blues Hall of Fame acknowledged that when it made Waterman its first non-performer inductee in 2000.

Musical beginnings

Born July 14, 1935, Waterman was raised in Plymouth, Massachusetts, roughly 1,100 miles from the Mississippi Delta whose music he championed. He’s cited his first musical passion as Dixieland – both the Chicago and New Orleans styles, but more the latter as personified by Louie Armstrong and Kid Ory – and as a teenager he also enjoyed early rock ‘n’ rollers like Dion and Buddy Holly. By the time he was in his early 20s, he’d added reggae and calypso to his musical diet.

After graduating from high school and serving in the Army, Waterman enrolled at Boston University, majoring in journalism and writing mostly about boxing, football and baseball, his favorite player being Joe DiMaggio and his favorite team being the New York Yankees. “I was a contrary kid,” he explained in the “Blues Savior” interview. “Who does everybody [in Boston] love? Red Sox. Who does everybody hate? Yankees. So I said, ‘That’s my team!’”

Move to Cambridge, The Broadside, Early promotions

Around 1961, when the folk revival was at full tilt, Waterman moved to Cambridge, an epicenter of the thriving scene on par with Greenwich Village, where he became enthralled with folk blues, also known as “country blues,” “rural blues,” “downhome blues” and “backwoods blues.” He’d already seen a number of acclaimed artists of the genre perform in New York, including Reverend Gary Davis, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee, Jesse Fuller and Josh White, but his interest deepened through his exposure to the thriving scene in Cambridge.

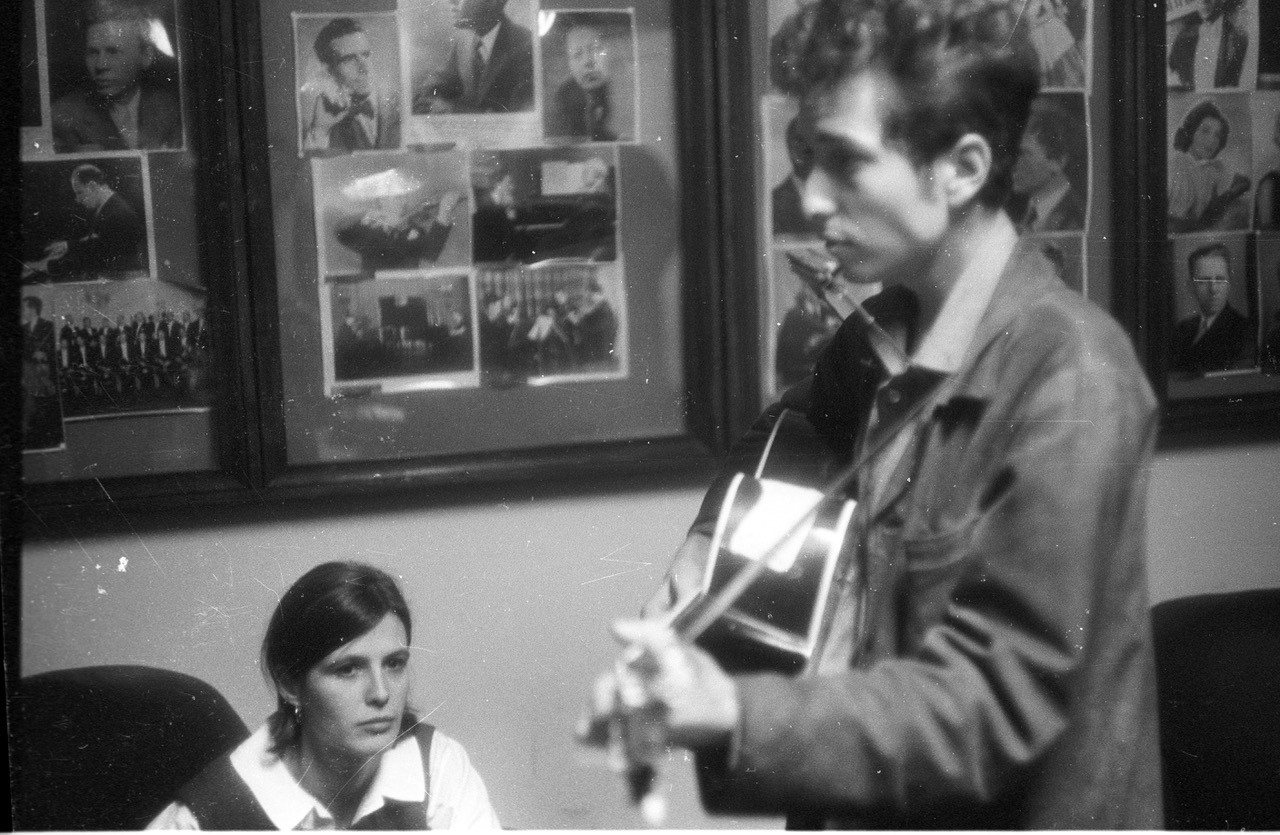

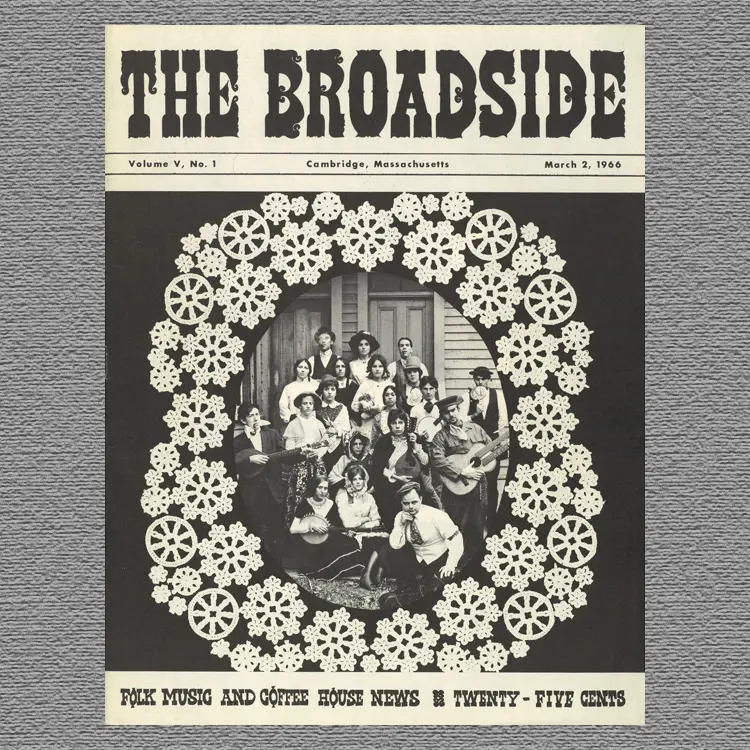

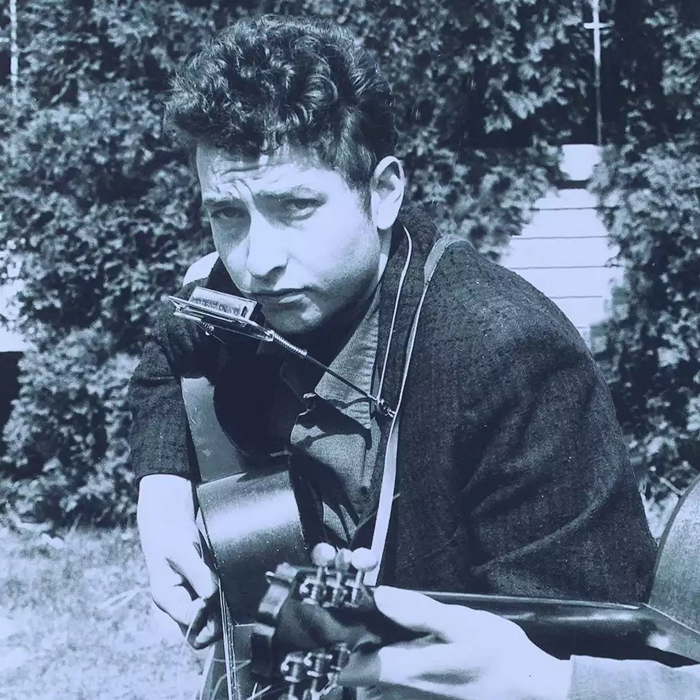

In 1962, he began submitting articles to the Cambridge-based folk bi-weekly The Broadside, including front-page stories on Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk and Woody Guthrie, and in 1963 he became the paper’s features editor. “I moved to Cambridge in the ’60s and I was very fortunate to be there with Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, Tom Rush, Tim Hardin, all of those people,” he said in a 2015 interview. “Just a really good time to be there. Really great people.”

In 1963, Waterman began promoting shows in Cambridge and Boston featuring artists including Mississippi John Hurt, Booker “Bukka” White and Mississippi Fred McDowell – who, despite his snappy stage name, grew up in Tennessee – but at the time he viewed doing so as a temporary hiatus from writing. “I thought, ‘I’ll do this music thing for a few months or so and go back to sports writing,’” he said in 2015.

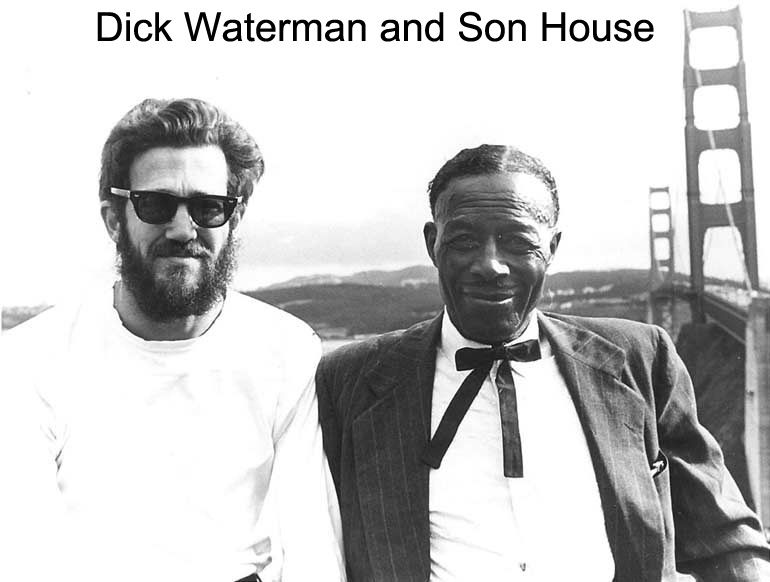

Finding, Booking, Managing Son House

But in June 1964, everything changed. Initiated by discussions with Bukka White about legendary bluesman Son House’s whereabouts, Watermen and two friends, Nick Perls and Phil Spiro – all passionate collectors of folk-blues 78s – traveled to the Mississippi Delta to find the reclusive singer, who was a formative influence on Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and others in the 1930s but had been out of the public eye since around 1943. After about a month of searching, they found House living in Rochester, New York, and Waterman booked the 63-year old to perform in Cambridge in early July.

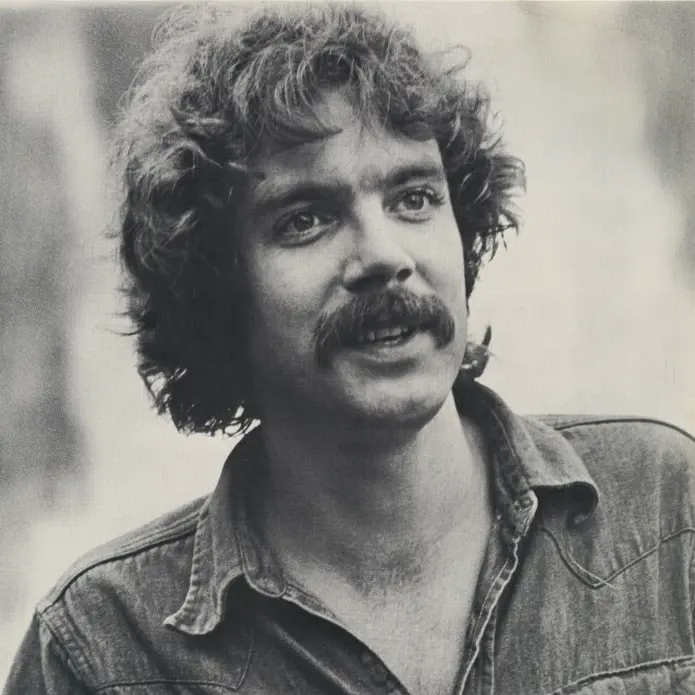

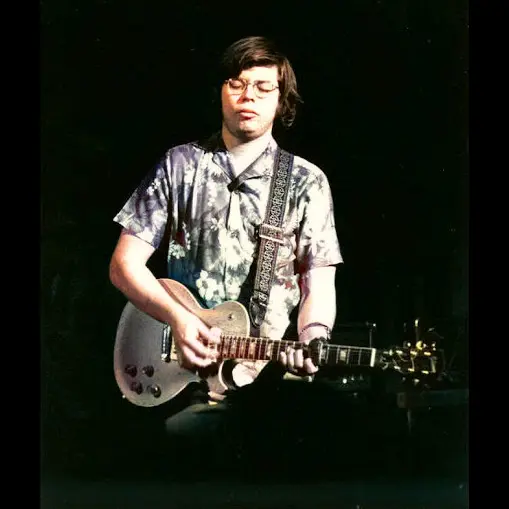

Emaciated and ashen after decades of heavy drinking, House had forgotten how to play many of his songs, so 21-year old Arlington native Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson, later the co-founder of Canned Heat, helped him relearn them. House went on to play at the Newport Folk Festival that summer and, with his career jumpstarted thanks largely to Waterman (who landed him a contract with Columbia Records), recorded his final two albums, Father of Folk Blues (Columbia, 1965) and Delta Blues and Spirituals (Capitol, 1995, recorded in 1970), with Wilson playing guitar on each.

Avalon Productions, Move to Chicago

By 1965, inspired by House’s astonishing comeback, a host of other artists asked Waterman to manage them, including Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James and Mississippi Fred McDowell, prompting Waterman to establish Avalon Productions, the first management agency to handle blues artists exclusively, which he named after Hurt’s hometown in central Mississippi, where the shotgun shack in which he was raised has been turned into a museum.

Around 1967, Chicago-based producer and Delmark Records founder Bob Koester – who also ran the Jazz Record Mart in that city, promoted as “the world’s largest jazz and blues specialty store” – encouraged Waterman to bring his management skills westward. “He said, ‘There’s a lot of young musicians here in Chicago that are dying to get out and are really talented,’” Waterman recalled in 2020. “’Muddy’s on the road and [Howlin’] Wolf is on the road and there’s a lot of guys that really need your help.’”

Taking the advice, Waterman soon found himself in the Windy City signing Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Luther Allison, J.B. Hutto, Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins, Magic Sam, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Mance Lipscomb, Robert Pete Williams, Otis Rush and others to management deals. “As the years went by, I realized I wasn’t going back to being a sports writer and that this music thing was what I was going to do,” he said in a 2015 interview.

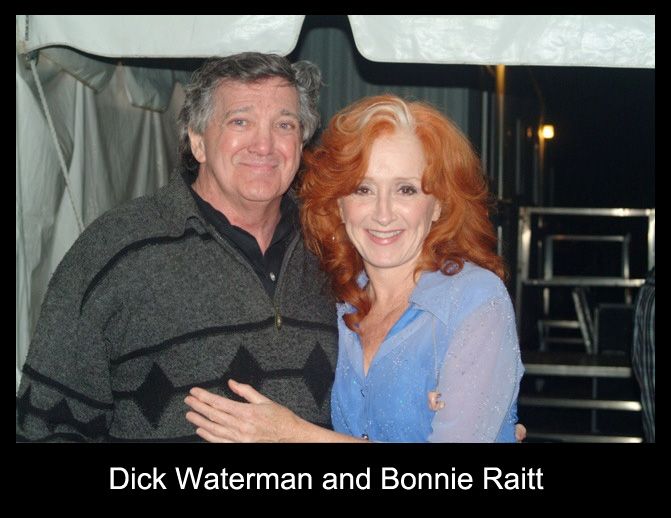

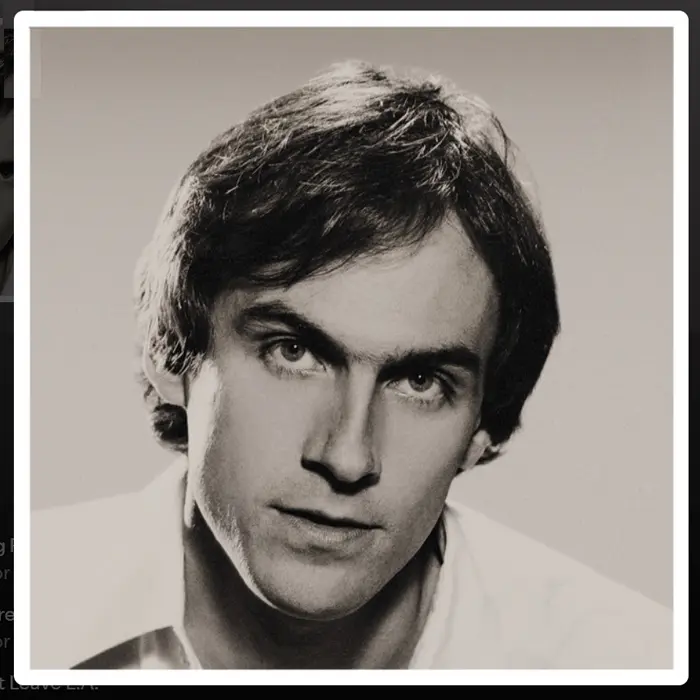

Discovering, managing Bonnie Raitt, Other notable artists

“About ‘69 or so, I met Bonnie Raitt who was going to college [at Radcliffe in Cambridge],” he said in the same 2015 interview. “I got her a contract with Warner Brothers. That kind of moved me into a different level. I was now into big band, pop, rock ‘n’ roll kind of stuff.” In mid-1970, Waterman landed 20-year old Raitt a spot as the opener for The Rolling Stones on their 18-city, September/October tour of Europe; he was her manager for the next 15 years.

“Dick and I became close friends, much to the chagrin of my parents, who didn’t expect their daughter to be running around with 65-year-old bluesmen,” Raitt told O, The Oprah Magazine in 2002. “I was amazed by his passion for the music and the integrity with which he managed the musicians.”

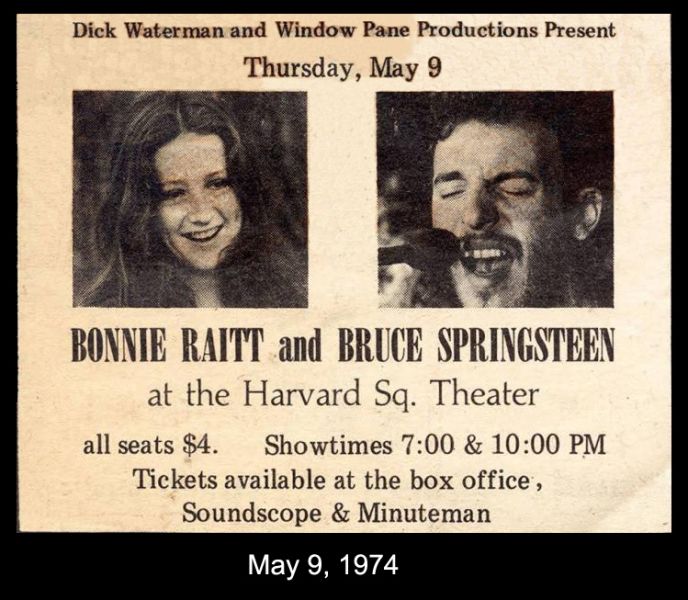

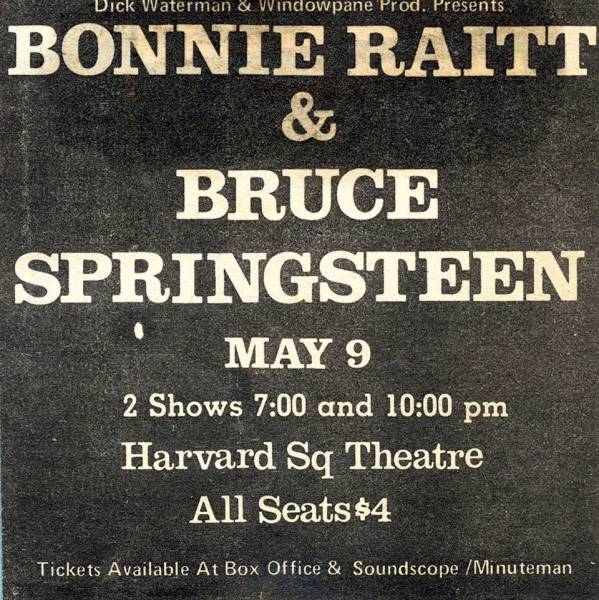

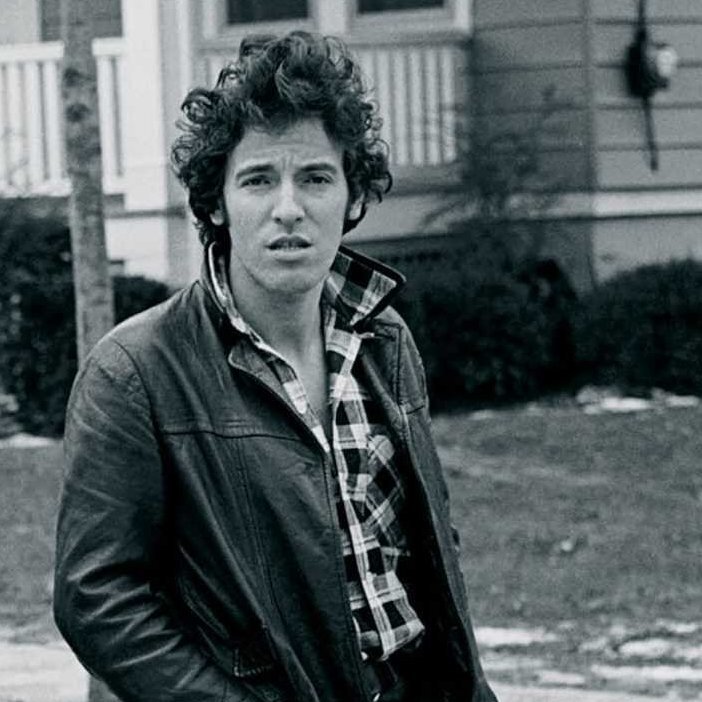

While maintaining his impressive list of managerial clients, virtually all of them born in the very early 20th century, Waterman also became an active promotor of concerts by artists of Raitt’s generation including Bruce Springsteen, Cat Stevens, Eric Clapton and James Taylor while coordinating shows for blues greats such as B.B. King and John Lee Hooker.

Clients’ rights, Royalties advocate

A tireless advocate for his clients, Waterman is known for his exhaustive efforts to protect them from commercial exploitation and for fighting for all monies due. He was instrumental in recovering the royalties owed to Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup after Crudup went uncompensated for the covers of his songs that Elvis Presley sold in the millions, and Avalon Productions continues to take care of the estates of many artists Waterman managed. In 1993, with funding from Raitt through the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund, Waterman arranged to place a new headstone on the grave of Mississippi Fred McDowell, as his name had been misspelled and his year of birth was incorrect on the original one.

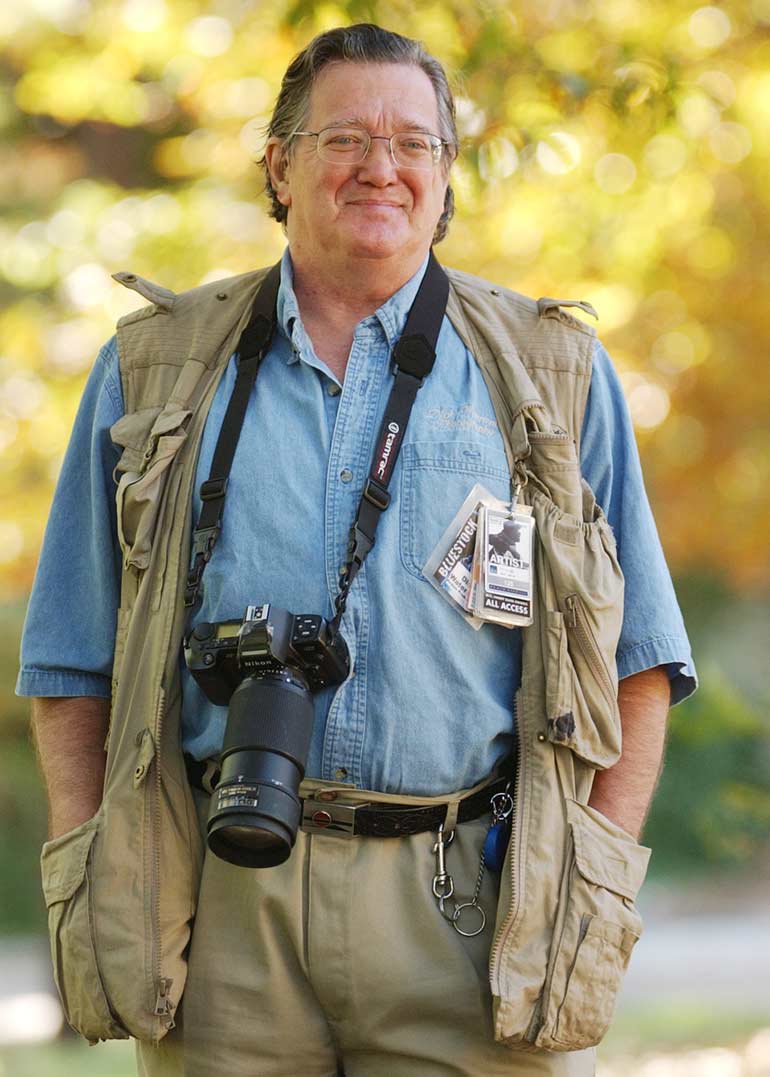

Move to Mississippi, photography career

In the 1980s, after spending much of the ‘70s living in Philadelphia, Waterman moved to Oxford, Mississippi, and began a new career publishing the photos of blues, folk, country and jazz artists that he’d take since the early ‘60s. His work is displayed in A Gallery For Fine Photography in New Orleans and The Govinda Gallery in Washington, DC. In 2004, Insight Editions published Between Midnight and Day – The Last Unpublished Blues Archive, a collection of 100 of his images – many taken at folk and blues festivals across the US – that is now out of print but remains available on Waterman’s website.

Awards, Accolades, Authorized biography

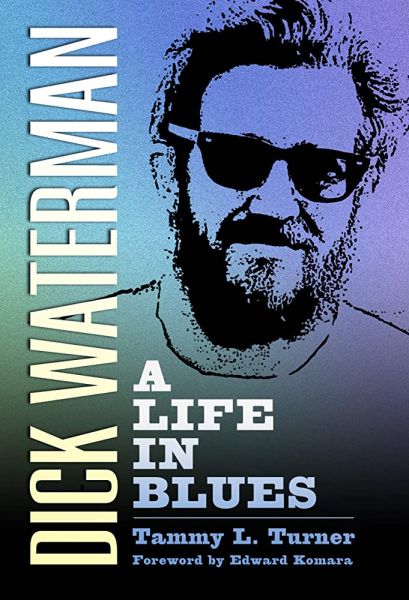

In 2014, Waterman received a Keeping the Blues Alive Award for Photography from the Memphis-based Blues Foundation, in 2017 he received a Brass Note on Beale Street in Memphis and in 2020 he was induced into the Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis. In 2019, University Press of Mississippi published the authorized biography Dick Waterman: A Life in Blues, gleaned from interviews with Waterman himself and over 40 others who worked with him.

Comments on Blues Hall of Fame induction

Asked in 2015 about his induction into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2000, the year an exhibition of his photographs was presented at the Russell Senate Office Building in Washington, DC, Waterman demonstrated characteristic optimism and humility. “Well, I have a tendency to feel that if you do something long enough, something good will come,” said the 87-year-old “blues savior,” who lives in Mississippi to this day. “And when you look around and you see Muddy and B.B. and Wolf and Son and Charlie Patton and those people and they say, ‘You’re their equal, we want you to come into the Hall of Fame,’ well, that’s just very special.”

DEATH, LEGACY

Dick Waterman died on January 26, 2024, at an assisted-living center in Oxford, Mississippi, at age 88. According to K.T. Leary, his longtime friend and executor of his will, the cause was congestive heart failure. “Mr. Waterman’s photos, direct and often poignant, reflected the intimacy and rapport he had with the musicians he chronicled and represented,” wrote The Washington Post‘s Harrison Smith in a detailed obituary.

“Waterman was up close with pivotal artists in a most personal way,” wrote Don Wilcock in an obituary published in American Blues Scene. “He changed their lifestyle from day laborers to full-time musicians with enough money to live in relative comfort. And he did this from the perspective of having a degree in journalism from Boston University and an ability to be extremely anecdotal. He could take you there.”

(by D.S. Monahan)