David Bieber

Where can you find what Dan McCarthy of Sensi magazine called “the Mount Olympus of pop-culture booty” and Joseph Baldassare of Arthouse 18 said is “the largest collection of pop culture on Earth”? Greenwich Village? Nope. Los Angeles? Nope. London? Nope. Tokyo? Nope, nope, nope.

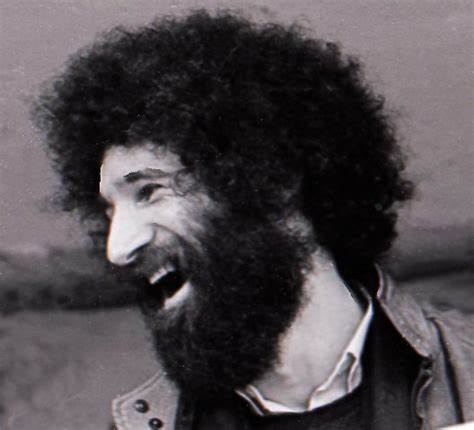

Try Norwood, Massachusetts, a town of some 32,000 about 13 miles outside Boston. That’s where journalist, radio man and collector extraordinaire David Bieber keeps north of a million pieces of memorabilia that he’s amassed over some seven decades, a treasure trove that simultaneously stuns anyone with eyesight and redefines the term “pack rat.”

OVERVIEW

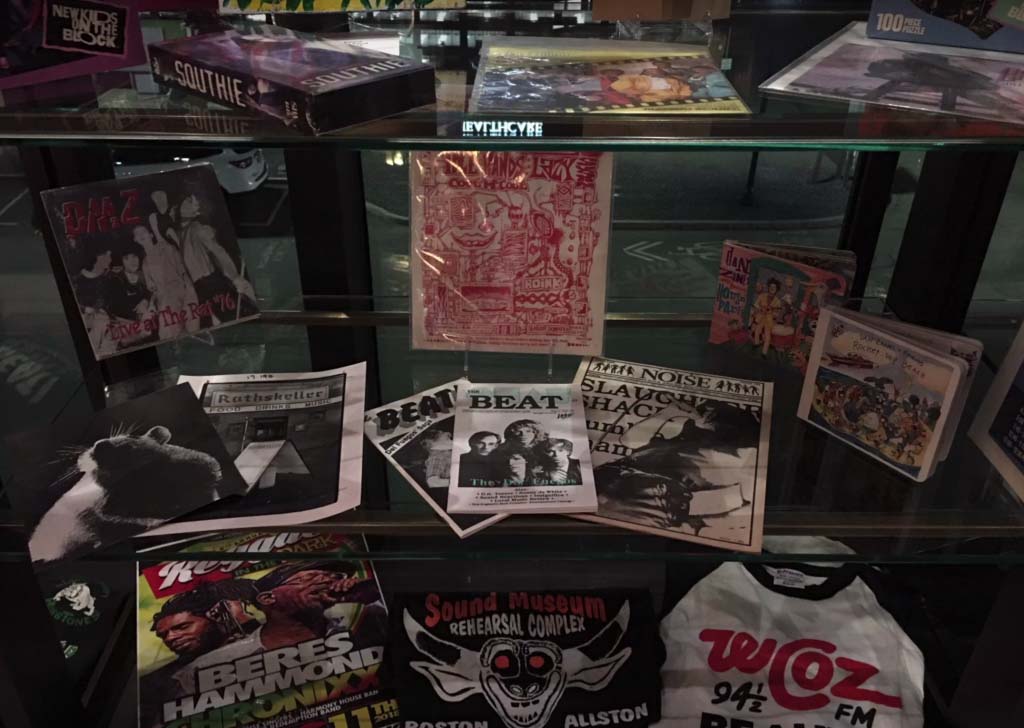

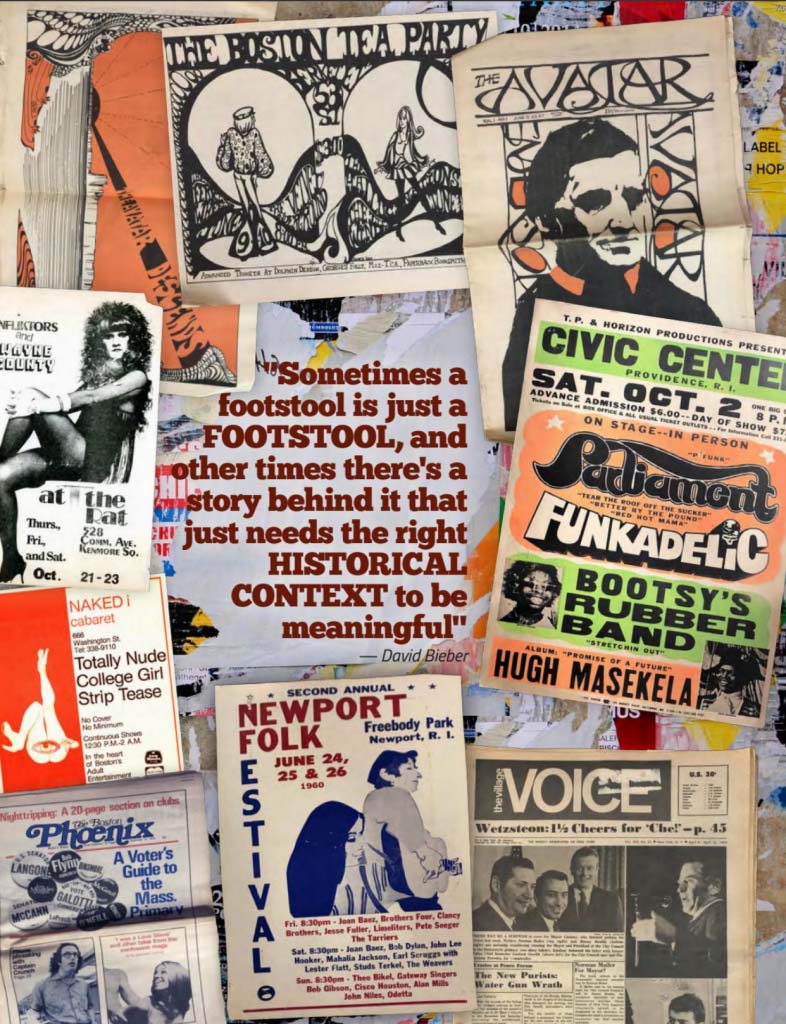

Bieber’s vast archives present a panorama of 20th- and 21st-century popular music, including vinyl albums, 45s, cassettes, eight-tracks, reel-to-reels, VHS videos, CDs, DVDs, concert posters, record-store displays, promo material, t-shirts, ticket stubs, backstage passes, instruments, fanzines, autographs and photos. But the collection isn’t limited to music-related items; it also includes a gobsmacking assortment of books, magazines, newspapers, political banners, comics, press kits, artwork, theatre displays, toys, games, bottles, bottlecaps, trading cards, cans, signage, televisions, stereos, radios, telephones, clothing, dolls, furniture, packaging and other kitschy ephemera.

Bieber’s bevy of notable nostalgia isn’t a museum, however, nor are any of his artifacts for sale. “The archives are not open to the public,” he told the online site Music Mecca in October 2023, “but I want the content to be as available as possible,” adding that he’s held open houses for “a handful of people.”

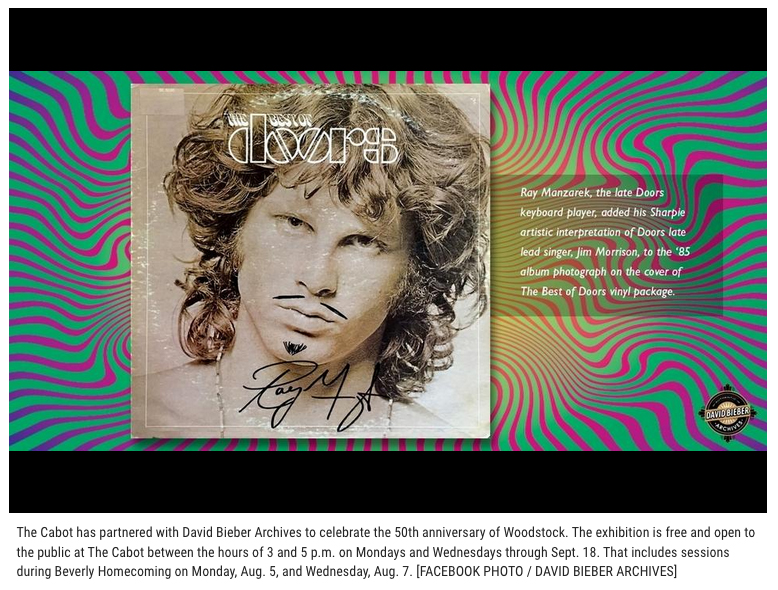

Instead, Bieber leases the items to businesses, non-profits and other entities through the David Bieber Archives – “a multi-disciplined pop-culture media and memorabilia company,” according to its official website – for use in exhibits, installations, publications, documentaries, panels, discussion groups and other purposes. He’s created, contributed to or consulted on projects for The Verb Hotel and The Boch Center in Boston, The Cabot Performing Arts Center in Beverly, the Smithsonian Institution and the audio-streaming platform Spotify, among others.

SCOPE, INTERCONNECTIVITY

While Bieber says he doesn’t know the exact number of pieces, he ventured a guess in a 2021 Boston Uncommon podcast. “I don’t have the ability to count it all but it ranges anywhere from a million and a quarter to a million and a half,” he told the host, Joe Mazzei, adding that there are “probably 125,000” vinyl LPs and 45s.

Asked why he’s kept such a smorgasbord of seemingly random stuff – vintage, modern, commonplace, rare – he said it’s all linked on a certain level. “I like to make a story about the connectivity of everything in our world and how one thing relates to another,” he said. “I want people to connect the dots and see how our culture has spawned, how everything along the way has led us to today. That’s the exciting thing.”

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, EARLY COLLECTING

Born in 1945 and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Bieber says his earliest exposure to music was hearing old-school crooners and pop divas on the family radio that sat atop their kitchen table. “The soundtrack of our life in the 1950s was Patti Page, Eddie Fisher, Johnny Mathis, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Julius LaRosa and Perry Como,” he told Charles Guiliano of Berkshire Fine Arts in 2019. “It was all very safe. For my generation of teenagers in America, we were straight, white and naïve. We made out, but few went all the way.”

In 1958, his parents bought their first turntable so that 13-year-old Bieber could listen to a recording their rabbi had made of the Hebrew songs he was supposed to learn for his bar mitzvah. While attending high school in the early ‘60s, Bieber fell I love with rock ‘n’ roll and – just as significantly – discovered Billboard magazine, which he began reading weekly and for which he wrote while in college.

Bieber told Boston Uncommon’s Mazzei that he collected the same things many kids of his generation did in the 1950s – comics books, baseball cards, marbles – but said his first fascination was with bottle caps, which he began collecting during a family road trip from Cleveland to Montgomery, Alabama, where his father was stationed during World War II. “We stopped at gas stations along the way and I was fascinated by the soda machines, where people would open their soda and the bottle cap would stay behind in a little container,” he said. “I was fascinated by the colors and the designs because they had all these different regional brands that I’d never seen in Cleveland. I started collecting those – fistfuls of them! I was probably about three or four years old.”

UNIVERSITY YEARS, BILLBOARD, MOVE TO BOSTON, WBUR

In September 1963, Bieber enrolled at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, as a business major. After reading a notice in Billboard that the magazine was looking for on-campus correspondents, he leapt at the opportunity. “I had a Billboard reporter’s card and I was off to the races,” he said in 2019. He wrote for the bellwether publication for over four years, submitting concert reviews and interviewing artists including Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, Cannonball Adderley and Frankie Valli and celebrities such as Johnny Carson.

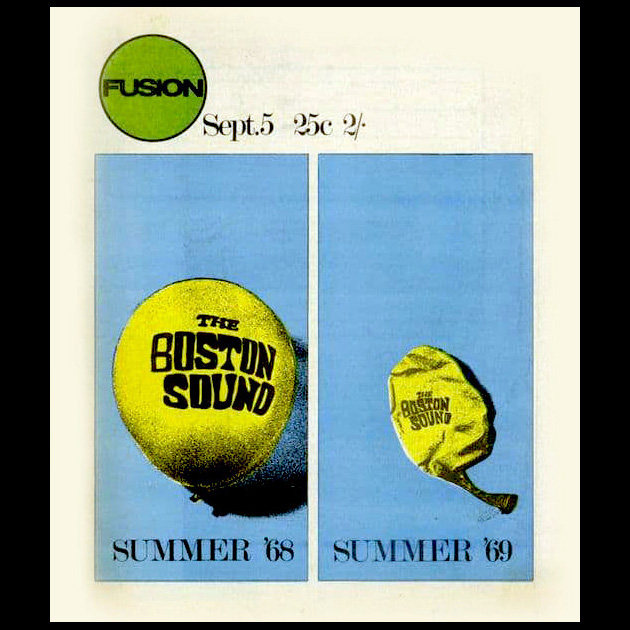

In his sophomore year, when he took a class in journalism – which included photography at the time, not only writing – Bieber decided against pursuing a business degree and transferred to Kent State University as a public relations major. In September 1968, he enrolled at Boston University’s School of Public Communications, earning a master’s in journalism in August 1970 after writing a 150-page thesis on the rise of alternative media. In addition to his Billboard work, Bieber contributed writing and photos to the alternative weekly Boston After Dark and Fusion magazine, among others.

In September 1970, after showing his thesis to the assistant general manager of BU’s 50,000-watt WBUR-FM, Bieber became the station’s music director and began hosting programs himself occasionally. The job ended just a year later, though, when newly hired BU President John Silber slashed the station’s staff from 32 to three.

MUSIC PROMOTIONS, WCOZ, WEEI

In early 1971, Bieber joined Boston-based Music Promotions, an advertising firm that worked closely with the Warner, Elektra and Atlantic labels and did some projects for RCA, ABC, Impulse and others. After Music Promotions shut down in 1973, he freelanced for labels in 1974 and much of 1975 before taking a position in the ad department at WCOZ, the biggest competitor to the station he most admired, WBCN. “I was totally intrigued by WBCN, but they weren’t really paying any money then,” he said in 2019. “It was heartbreaking for me to work for their competitors, but I did.” In 1977, he worked at WEEI, Boston’s soft-rock leader at the time.

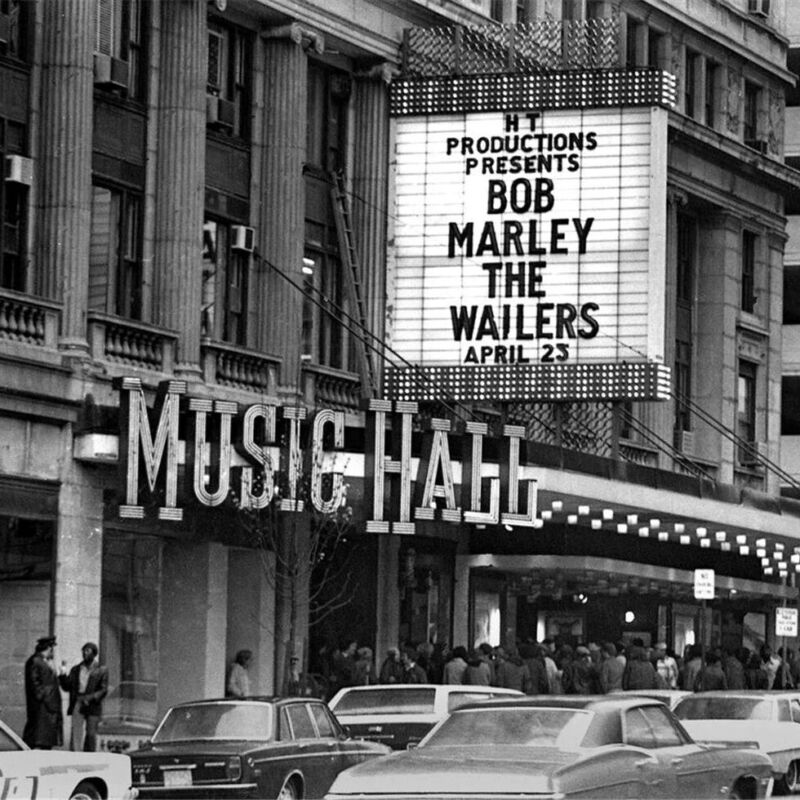

WBCN, ROCK ‘N’ ROLL RUMBLE, WFNX, THE BOSTON PHOENIX

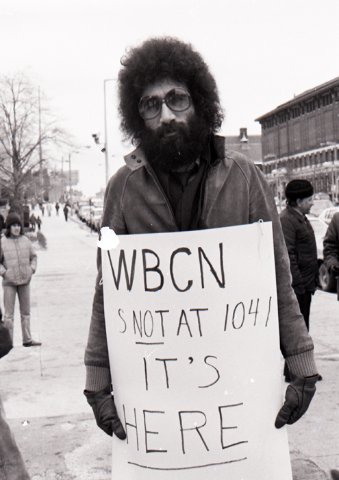

In 1978, Bieber began his 16-year run as creative services director at WBCN. Asked in the Boston Uncommon podcast about his fondest memories, he said one was co-creating the First Annual Spring Rock ‘n’ Roll Festival in 1978 (aka “Rumble Number Zero,” won by La Peste), which was co-sponsored by Inn-Square Men’s Bar in Cambridge and WBCN and was renamed the WBCN Rock ‘n’ Roll Rumble in 1979. “Eddie [Gorodetsky, then WBCN’s head writer] and I came up with the name and concept based on the instrumental song ‘Rumble’ [Link Wray & His Wray Men, 1958],” he said. “We created it not so much as a competition but as a fun event that celebrated local music.”

Soon after joining ‘BCN, Bieber realized he needed significantly more room for his growing collection of music memorabilia. “For most of the ‘70s, I could still live with everything I was acquiring but when I got the full-time job at WBCN in ’78, the onslaught of content was so overwhelming that I had to start taking warehouse space,” he said in 2019. He contributed about 50 items to the 2020 documentary WBCN and the American Revolution.

Bieber left ‘BCN in 1994 to become director of special projects at WFNX, the Lynn, Massachusetts-based station established in 1983 by Stephen Mindich, owner/publisher of The Boston Phoenix. For the next 19 years, until Mindich sold the station and shuttered the paper in 2013, he worked on initiatives for both ‘FNX and the Phoenix.

NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY, THE VERB HOTEL

In 2013, he helped Mindich get the archives from The Boston Phoenix and other Phoenix Media Communication Group companies placed in Northeastern University’s special collections, which he says was an invaluable experience. “Doing that kind of gave me a lesson in more formal archiving,” he said in the Boston Uncommon podcast.

But by far the biggest boost Mindich provided came in early 2014 when he introduced Bieber to Steve Samuels, the owner of Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge Inn at 1271 Boylston Street, which he was converting into the music-inspired Verb Hotel. Bieber and Samuels struck a five-year deal (expanded to 10 years shortly thereafter) for items to be displayed in the lobby; initially, Bieber installed a mere fraction what he kept at home – nothing from his warehouse.

“I was able to do The Verb Hotel based on the one tenth of one percent of works that I had in my house,” he told Berkshire Fine Arts’ Guiliano, adding that he had 230 pallets of memorabilia stored in Avon, Massachusetts, at the time. “My monthly rental bill was brutal,” he said. “I was paying for something that was largely a mirage since nobody had ever seen it or used it.” In the Boston Uncommon podcast, Bieber said the unexpected Verb Hotel project was “like the hand of God from the side of the stage because I had no idea this was going to be like my ‘second act.’”

MOVE TO NORWOOD, OFF OUR BACKS: 150 T-SHIRTS

In 2017, Bieber moved his passion project – some 8,500 boxes – from Avon to Norwood, storing them in an old industrial building called Norwood Space Center, a 10,000-square-foot mixed-used space that was once part of a paper mill. “It’s not laid out like a boring old ‘museum’ but rather like your really hip uncle curated it,” wrote Paul Howard in Music Mecca. Eventually, Bieber wants to have an exhibition at the Space Center like the one at The Verb Hotel, he told The Boston Globe in 2018.

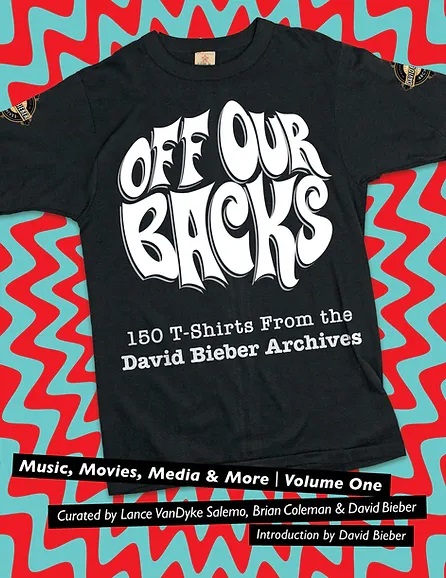

In September 2021, the David Bieber Archives published its first book, Off Our Backs: 150 T-Shirts from the David Bieber Archives, which features 150 photos of t-shirts from the ‘60s onward. Culled from Bieber’s collection of roughly 5,000, some celebrate Boston-based bands and others feature artists as diverse as George Jones and Janet Jackson. The themes run the gamut from music and movies to sports, politics and retail chains. “These now-historic and valued shirts were a badge of honor,” Bieber writes in the book’s forward, “a sort of visible secret handshake.”

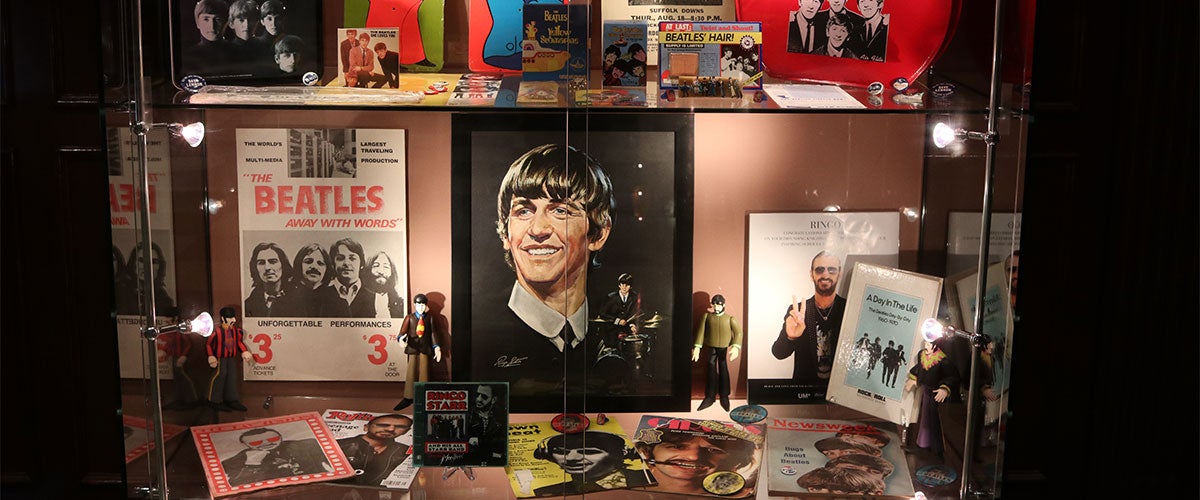

COMMENTS ON FAVORITE ITEMS, SHARING

When Boston Uncommon’s Mazzei asked him about particularly prized pieces, Bieber talked about one that he’s had for 60 years. “When Meet the Beatles came out [in January 1964], there was a great window display in a record store in Cincinnati that had the Beatles’ heads on a motorized stand-up thing,” he explained. “I asked the store owner ‘Could I have that when you’re through with it?’ and he said, ‘You can have it now because they’re sending me another one. This one’s busted.’ What had happened was, there were two heads of George and none of John, so I’m delighted to still have something like that. Such a very unique item!”

Asked what gives him the most satisfaction from his now world-renowned collection, Bieber said it’s sharing his stuff with others. “Really, the thing that’s given me the greatest pleasure is to put these things out there, just sharing them with people,” he said. “To reacquaint people, have people over here so I can say to them with confidence, ‘Your DNA’s probably on some of these items!’”

(by D.S. Monahan)