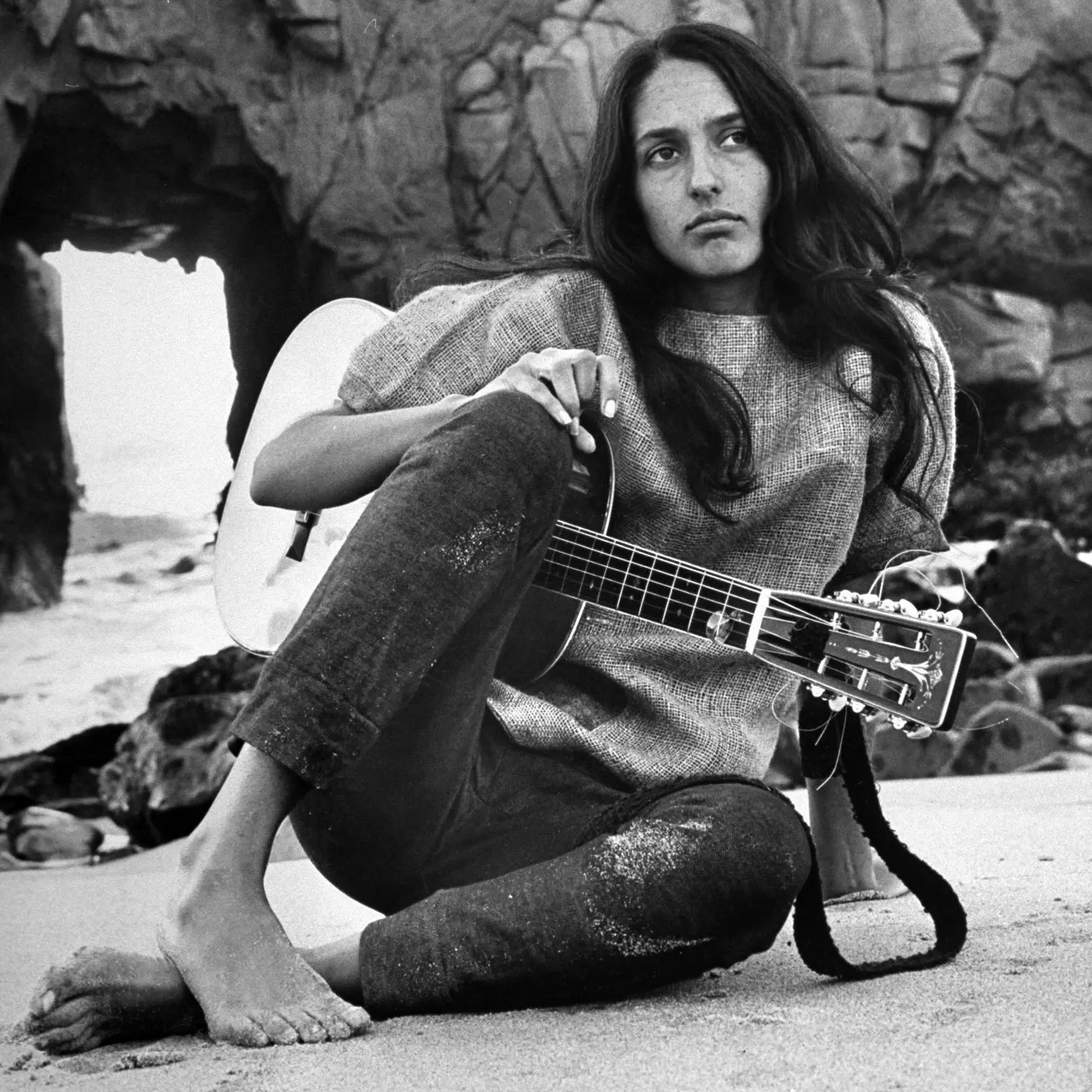

Dar Williams

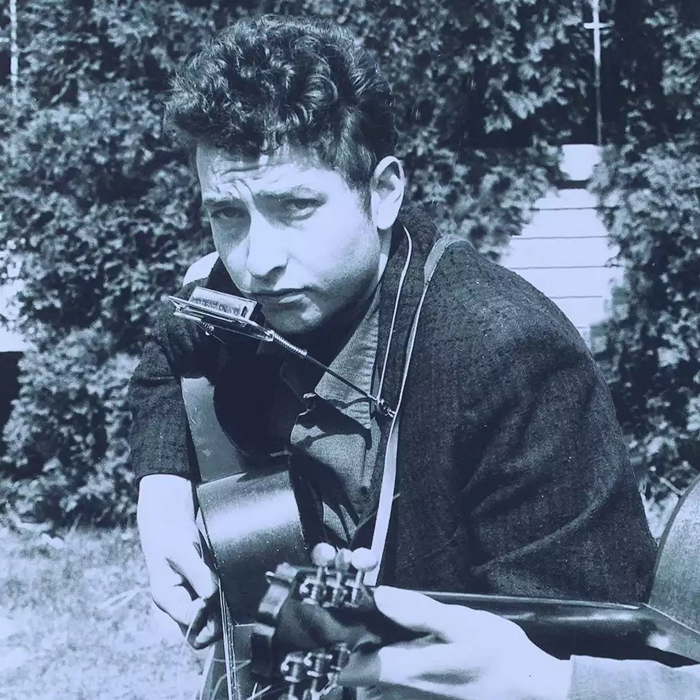

At the risk of oversimplification, you could say Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Chuck Berry and Bob Dylan built the foundation for rock and pop songwriting as we know it today. Guthrie contributed his outsized part in the ‘40s; Williams built on that in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s; Berry added swagger, hot licks and teen-friendly themes in the mid-to-late ‘50s; and Dylan mixed the styles of all three with sardonic sneer to create something radically “other” in the early-to-mid-‘60s.

But while those geniuses “wrote the book” on songwriting – and Dylan wrote essays about other artists’ material in The Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster, 2022) – none of them penned an actual book on how to put a tune together. Dar Williams has, though – How to Write a Song That Matters (Hachette, 2022) – and that shows how very seriously she takes her craft. It also demonstrates the blend of passion and vision that’s established her as one of contemporary folk’s most influential and oft-imitated figures.

OVERVIEW

With lyrics that combine acute observations and warm wit, Williams uses an eclectic range of musical expression – from finger-snapping pop to melancholic laments – and became a significant force on the folk scene around 1998, after the release of her third album. Along with Ellis Paul and Shawn Colvin, she’s part of what’s known as the “Boston school of songwriting,” a style that’s simultaneously literate, introspective, provocative, topical and romantic. In her book, she defines “as song that matters” as “something that gives a certain reality to poetic thinking in a way that helps us understand all our thinking.”

Williams is viewed as one of the most naturally gifted songwriters of the post-Beatles era. Though she appears frequently at folk festivals and many of her songs reflect traditional-folk influences, a significant number of her tunes are keester-kickin’ rockers and others have “top 40” scrawled all over them. On one album, she covers the Pink Floyd classic “Comfortably Numb.”

A prolific songwriter, Williams has recorded 14 LPs over the past 30 years. Her material addresses a broad range of themes including alienation, hypocrisy, religion, ageism, relationships, anti-commercialism and self-loathing. She often returns to the topics of gender roles, gender inequity and body image and has amassed a wide following in the LGBTQIA community. In a November 2001 profile in The Advocate subtitled “Dar to be different,” she explained what it’s like for her to be “a straight woman who gets the lesbian psyche.”

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Born Dorothy Snowden Williams on April 19, 1967 in Mount Kisco, New York, Williams was raised in Chappaqua (about 30 miles from New York City). She began using the nickname Dar because one of her sisters had trouble pronouncing ”Dorothy” and she has described her parents as “liberal and loving,” saying that they supported her songwriting career from its earliest stage.

Williams started playing guitar at age nine and began writing songs at age 11. She developed an enduring interest in theater after appearing in a high school production of Godspell and by the time she graduated she was writing plays. While at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, she studied theater and religion, took voice lessons and her rendition of her song “You’re Aging Well” appeared on the 1985 compilation Boston Women’s Voice.

The ever-eclectic nature of Williams’s material is no surprise considering what she cites as her three primary influences: her parents’ collection of folk-rock albums from the ’60s; her father’s love of classical music; and New York City radio of the mid-’70s, which played a virtually endless loop of disco.

MOVE TO BOSTON, OPEN-MIC NIGHTS

In 1990, Williams moved to Boston to begin a career in theatre – “a friend said I could get a bagel and a cappuccino for less than two dollars here,” she once joked – and landed a job at the Opera Company of Boston as a stage manager. She worked there for about a year, writing songs, recording demos and building up the nerve to sing in public, which she’d never done. “I went to a song circle, and decided that I had a crush on one of the guys there so I could pursue the open mics and pursue him at the same time,” she’s said.

Before long, she was a regular part of the local scene, playing open-mic nights at venues including the Old Vienna Kaffeehaus in Westborough and O’Brian’s Bar & Grill and the Nameless Coffeehouse in Cambridge, often sharing the stage with other up-and-comers like Ellis Paul, Shawn Colvin, Cheryl Wheeler, Patty Larkin, Vance Gilbert and Patty Griffin.

I HAVE NO HISTORY, ALL MY HEROES ARE DEAD, THE HONESTY ROOM

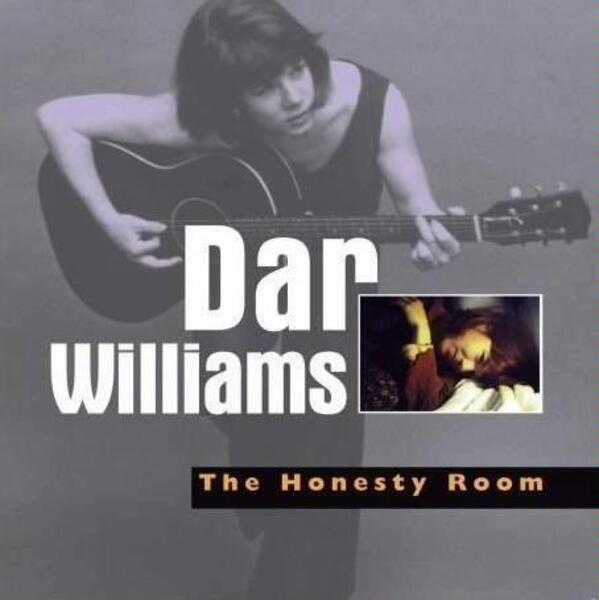

In 1990, Williams recorded a six-song, cassette-only EP I Have No History at Oak Grove Studios in Malden, Massachusetts. A year later, she recorded All My Heroes Are Dead (also on cassette only), mostly at Wellspring Sound in Newton. Among the tracks was “Mark Rothko Song,” which she included on her 1993 album, The Honesty Room.

In 1993, Williams moved to 100 miles west of Boston to Northampton, Massachusetts, and recorded her first vinyl disc, The Honesty Room, at Shoestring Studio in nearby Belchertown. Guest artists included Nerissa and Katryna Nields of The Nields and Williams released it on her own label, Burning Field Music. In 1995, she secured a licensing-and-distribution deal for Burning Field with Razor & Tie Records, which rereleased the LP in 1995 (with two re-recorded bonus tracks) and distributed Williams’ next 10 albums.

The record saw strong reviews overall and went on to become one of the top-selling independent folk albums of the year but was not without criticism. “Although she is a lyricist of striking originality and endearing humor, and although she can craft a hooky tune with the best of them, there’s still a certain preciousness that creeps in when she’s not being careful,” wrote critic Rick Anderson, “She [sings] with the light, fluttery consonants and flattened vowels that make so many of today’s female singer-songwriters sound like 13-year-olds.”

JOAN BAEZ, RING THEM BELLS, MORTAL CITY

All such critiques aside, Williams was about to get the biggest boost of her early career: After she opened at a Joan Baez concert, the folk legend was so impressed that she invited her to join a full tour featuring her, Indigo Girls, Mary Chapin Carpenter and Mary Black, captured on the live disc Ring Them Bells, released in 1995. On the LP, you hear Baez inviting Williams on stage for a duet of Williams’ song “You’re Aging Well.”

Williams showed her desire to stretch far beyond standard folk with her next album, 1996’s Mortal City, using a more aggressive approach on the rip-rockin’ opening track, “As Cool As I Am,” and a few others. Critics praised songs like “The Christians and the Pagans” for their hilarity and the album was very well received both critically and commercially. Guest artists included The Nields and singer-songwriter John Prine.

END OF THE SUMMER, CRY CRY CRY

By 1997, she recorded The End of the Summer, which was a major breakthrough because it sold extremely well considering that an independent label (Razor & Tie) released it. It was also the glossiest and most boisterous of her studio efforts to date which – in a reminder of Dylan “going electric” on his 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home and at the Newport Folk Festival that year – resulted in some fans criticizing her new direction. Others were effusive about the LP, including critic Anderson. “It’s slick,” he wrote, “but slick is only bad when it means soulless, and her soul is in fine shape.”

In 1998, Williams, Richard Shindell and Lucy Kaplansky formed the band Cry Cry Cry as a way to pay homage to some of their favorite folk artists. They released one album and toured from 1998 to 2000. The group reunited for benefit shows in 2017 and 2018, and in 2020 the online audio distribution company Bandcamp issued a recording of the group’s final show, Live @ the Freight.

2000S ALBUMS, BOOKS

Williams has recorded 10 albums since 2000, starting with that year’s The Green World. Others have been Out There Live (2001), The Beauty of the Rain (2003), My Better Self (2005), Live at Bearsville Theatre (2007), Promised Land (2008), Many Great Companions (2010), In the Time of Gods (2012), Keeping Me Honest (2014) and Emerald (2015), the last one on her own label, Dar Williams Records, with guest artists Richard Thompson, Jim Lauderdale and Jull Sobule. Williams’s most recent studio outing is 2021’s I’ll Meet You Here on the Renew label, an Americana imprint distributed by BMG. “Every song is a grand slam in its own way,” wrote Jon Apice in Americana Highways. “Maybe Dar has finally found her niche.”

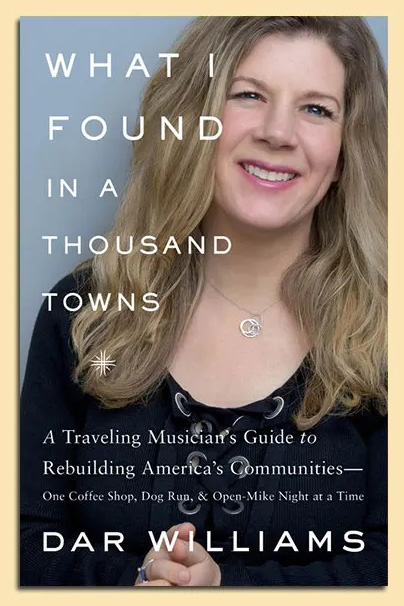

In addition to How to Write a Song That Matters, Williams is the author of The Tofu Tollbooth: A Directory of Great Natural & Organic Food Stores (Ardwork Press, 1994), which was inspired by her inability to find suitable dining during months on the road. She co-authored a second edition with Elizabeth Zipern. She has also written two works of fiction, Amalee (Scholastic, 2004) and Lights, Camera, Amalee (Scholastic, 2006), and a review of why she believes some towns flourish and others fail called What I Found in a Thousand Towns: A Traveling Musicians Guide to Rebuilding America’s Communities – One Coffee Shop, Dog Run, & Open-Mike Night at a Time (Basic Books, 2017).

COMMENTS ON SONGWRITING

Williams has called herself a “lazy, distracted person” except when it comes to writing and performing music; when she has an idea for a new song, she tries to be as attentive as possible. “If a weird song comes through my head,” she once said, “I don’t ever dismiss it. I assume that it’s a growth opportunity.”

Asked in a 2021 interview how she gets the ideas for her songs, she said that they’re usually the product of her innate curiosity. “You know, a little thing will pop into my mind. And I think at this age [then 54]…you take that little thing seriously, and you follow it,” she told NPR’s Scott Simon on Weekend Edition. “So with the song ‘Time, Be My Friend’ [from 2021’s I’ll Meet You Here], thought, well, haven’t I been a good friend to time? And I thought, ’no, I haven’t been a good friend [laughter].’

“And that’s when I start what I call ‘the file cabinet’ around all of the times that I have either been a good friend to time or have not, what I’ve asked time to do for me and how things have turned out when I’ve let that go and let time do its thing. So that’s how songs start. A little phrase comes in. And then I get curious about it. And I explore it.”

(by D.S. Monahan)