DAAAAAHHHHHEEEEE: In Praise of Guitar Feedback

Lou Reed's Drones

The guitar has been around for at least 900 years. But in the 1940s and 1950s it evolved into something else altogether, not an acoustic instrument that projected the vibrations of its strings from its hollow body, but essentially an input device to control the electronics of an amplifier which emitted the sounds. The Fifties rock ‘n’ roll pioneer Bo Diddley played a guitar with a cigar-box shaped body that loudly proclaimed “this ain’t no acoustic guitar.”

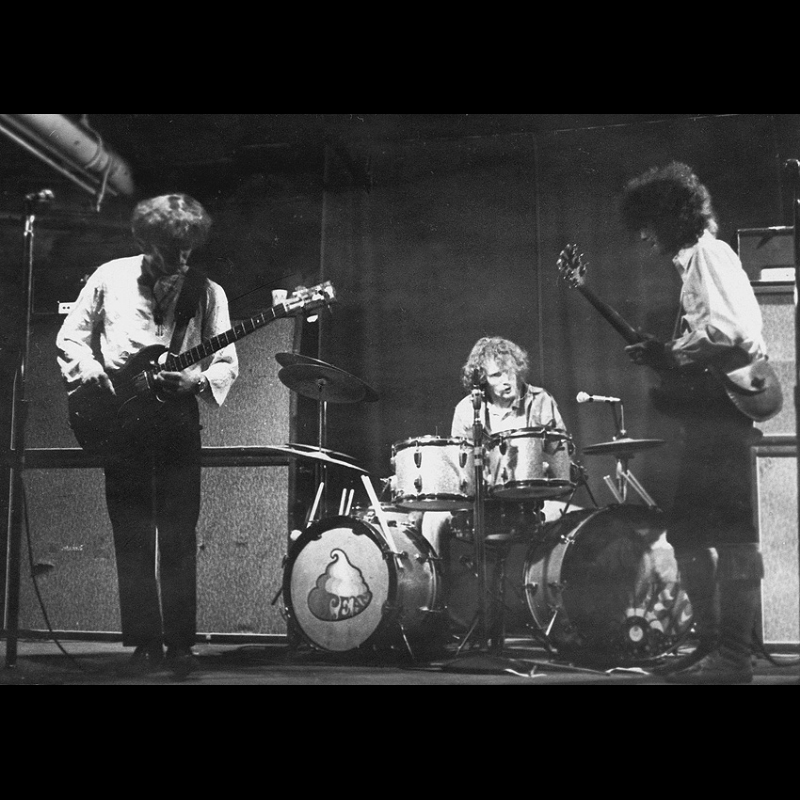

The musical explosion of the 1960s was driven by musicians exploring new sounds they could wring from their electric instruments live and with the evolving electronics of the recording studio — guitar gods like Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, B.B. King, and many more. Name your favorite.

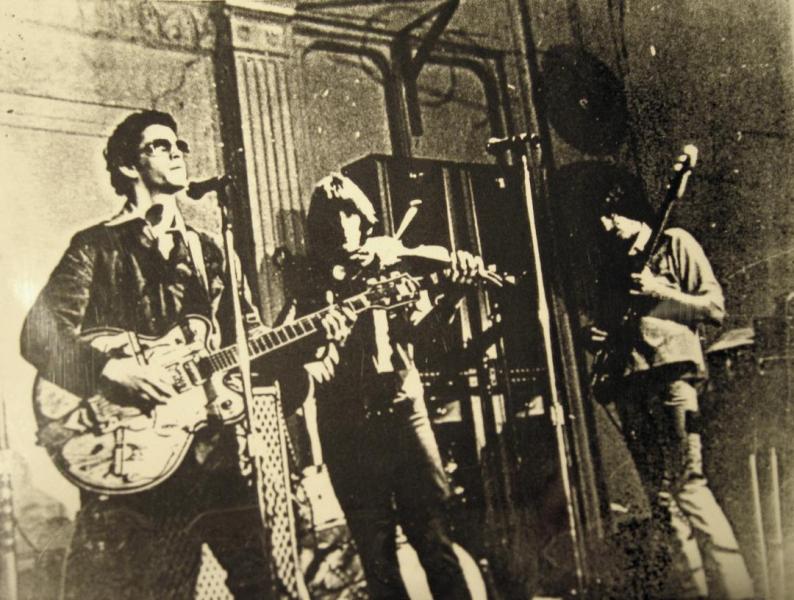

In the late Sixties I was a rock concert producer in Boston and western Massachusetts, and promoted many shows with a band that to me was one of the most exciting and innovative of that era, The Velvet Underground. Rolling Stone magazine later agreed, recalling them as “the most influential American rock band of all time.” Their leader Lou Reed usually played rhythm guitar, but took off on wild flights of soloing and feedback. Lead guitarist Sterling Morrison entwined rockabilly and country-inflected playing with Lou’s burning guitar runs. When the Velvets did a twenty-minute rendition of their classic “Sister Ray” at The Boston Tea Party, their favorite place to play, the whole room vibrated.

In a 1978 interview with the Los Angeles weekly newspaper Open City (“All Tomorrow’s Parties,” Issue #78) Lou explained what he’d experienced with the VU playing a guitar with a fuzz pedal: “You go like this on the fuzz, daaaaaaaaaa – and what happens is that you don’t get just one note like a guitar, you may get eight notes, like daaaaahhhhheeeee…. You start hearing some really strange things…. We used to call it the Cloud, and like, on certain songs, we used to consciously enter the Cloud and you just hear all these funny things. They’re not you, but you know they’re being caused by the guitar, right?”

On August 10, 2019, almost six years after Lou died, I attended a concert caused by his guitars, “Laurie Anderson Presents: Lou Reed Drones.” It was at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, where Laurie had long been involved with events and exhibitions. When the doors opened, several hundred of us walked into the performance space, which was already resonating with the loud drone of feedback. In the dim light I took a seat in one of the folding chairs scattered around the floor, feeling a little unsteady from the sound swirling around me, while other people perched in bleacher seating. There was no stage as such, but I could see the source of the sound, an array of seven guitars leaning against seven amps in a semi-circle.

Lou had a large collection of instruments and amps, and was fastidious about their care, which was overseen by his guitar tech Stewart Hurwood. He and Laurie, Lou’s widow, had conceived this event. It was Stewart who “sets a soundscape foundation, manipulates and interacts with the guitars; the feedback is altered by the location and movement of people present in the space.” He explains that “what we’re dealing with is interference patterns so that guitars are going to be playing against each other” (RNZ Music, 3 March 2020).

Since there was no performer on whom to focus their attention, people did move around during the show, perhaps out of confusion or restlessness. They unintentionally became part of the performance by affecting the feedback. Some left well before the show ended, unable to endure being bombarded with sound at the decibel level of a jet engine. I recognized a couple of friends in the crowd, including Jay Reeg, a noted collector of Velvets memorabilia and former member of the board of the Andy Warhol Museum. He’d driven out from Boston for the event, but it was impossible to have a conversation above the din.

About halfway through the event Laurie came out and plugged in her solid-body electric violin. It was an instrument Stradivarius would not have recognized as anything he might have crafted. Playing at the opposite end of the hall from the guitars, she improvised along with the feedback, adding to the intensity of the sound. For me it harked back to the original Velvet Underground lineup with John Cale on electric viola, tearing up the Tea Party.

After the show I chatted with Stewart and Laurie about my connection to The Velvet Underground. I doubt there were many people in the audience, if any, who had seen them live, certainly not as many times as I had. I wondered, but did not ask, how she felt to be accompanying her late husband’s guitars.

I’d heard Lou using a lot of feedback in his solos, when he and Sterl were in “the Cloud.” Despite numerous recordings of the VU, I hadn’t heard any which fully captured the wild energy of those solos. Now I got a headful of feedback live for two straight hours of “Lou Reed Drones.” And on that night, the electric guitar had evolved to where it no longer needed a guitarist.

(by Steve Nelson)