I arrived quietly and without much fanfare to Boston in the summer of 1967, when the folk revival was in full bloom. Before then, while going to high school and college in Providence, I got my folky feet wet at the Tete a Tete Coffeehouse with my band, Loose Ends, which did quite well at fraternity parties covering early Stones, The Beatles, The Searchers and others acts of the era. One my friends and I opened a coffeehouse called Café Innisfree in the dining room of our University of Rhode Island fraternity house in the summer of 1963 that became quite popular. Paul Geremia was a regular and rocked the joint.

When I arrived in Boston, I rented a small room on Hancock Street that had a fire escape window where I put my little hibachi; a short walk to the North End for food completed my new home. I soon found out that Haskell’s Cafeteria on Charles Street was a popular gathering place and usually packed at mealtime, with Herbie, the owner, yelling, “Buy or goodbye! Don’t block the aisle!” And he allowed us, within reason, to play guitars and jam. One of the first musicians I met was Paul MacNeil, an extraordinary songwriter who influenced us all, and I covered a few of his songs (as did everybody else). Zelda was always there, sitting alone in a back booth reading and applauding for songs she liked, though getting applause from her was rare. Rocky Rockwood was always ready to add his great harmonica playing to the jams.

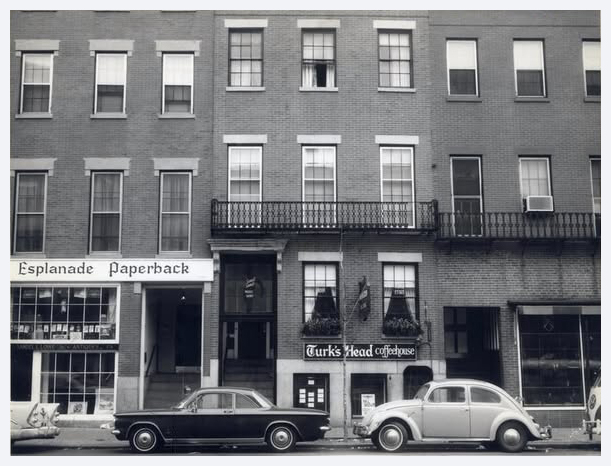

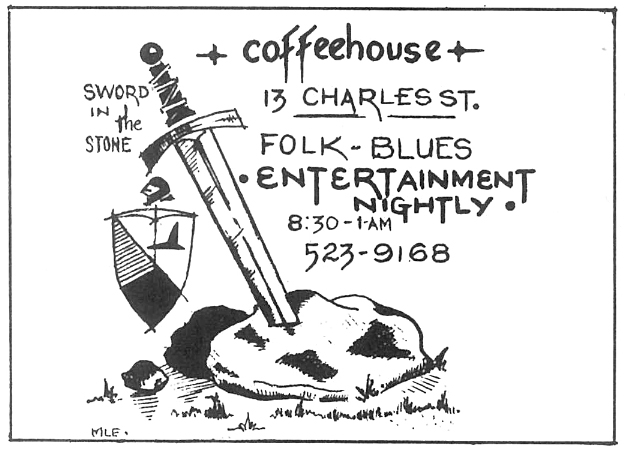

There were a bunch of popular coffeehouses on Charles Street including The Sword In The Stone, which was run by Mark Edwards, who wore a goatee and a beret – a reminder of the bygone beatnik era – and was very supportive but also argumentative with those who played at what he called “his Sword.” Another was the revered Turk’s Head Coffeehouse, run by Doc Cummins who, shortly after I arrived, sold it to Jossette Benzaquin, a flamboyant, lovely woman who at one point wanted to end the music there and turn it into a French bistro but never did. It was considered an honor to play there, and it was conveniently located next to The Sevens, a famous watering hole where you could sneak in a beer on your break when playing at the Turk’s.

The following spring, I rented a third-floor apartment on Revere Street that had a short stairway leading to the roof. I remember playing with Bill Staines at one of the many rooftop gatherings. He played guitar left-handed, I played right-handed, we both finger-picked and the sound was amazing. One morning, I was looking out the bay window from my apartment to Revere Street below and saw a rather beaten-up old two-seat Thunderbird drive up and park. In it was a beat-up-looking guy with blond hair and a guitar case in the passenger seat. Grabbing the guitar as he got out, he came up to my place, knocked on my door, asked if I was Bill Madison, said he hadn’t been able to find me anywhere and told me that he wanted us to play guitar together and become famous. His name was Kenny Girard, who remains one of the greatest guitarists I have ever met. Lightning fast and never missing a note, he blew everybody’s mind with his playing and quickly became a feature act at the Sword’s hoot nights, which were on Mondays and usually hosted by Sword regular Dan Gravas, a big, “bull in a china shop” kinda guy who lacked even a touch of finesse.

Gravas played thundering guitar, not always in perfect tune but always with huge rhythm, and acquired a reputation as our own “two-fisted guitar player.” Another regular at hoot nights was Alan B. Rotman, a master of Yiddish-laced comedy who considered nothing sacred. One night, he announced that he going to be a folk singer and put everyone to shame, borrowing a guitar, hitting the stage and starting to play Quicksilver Messenger Service’s “Pride Of Man.” When he reached the chorus, he sang it in his own, mispronounced way – “Oh God, the pwide of man bwoken in the dust again…” – and everyone was on the floor in fits of laughter.

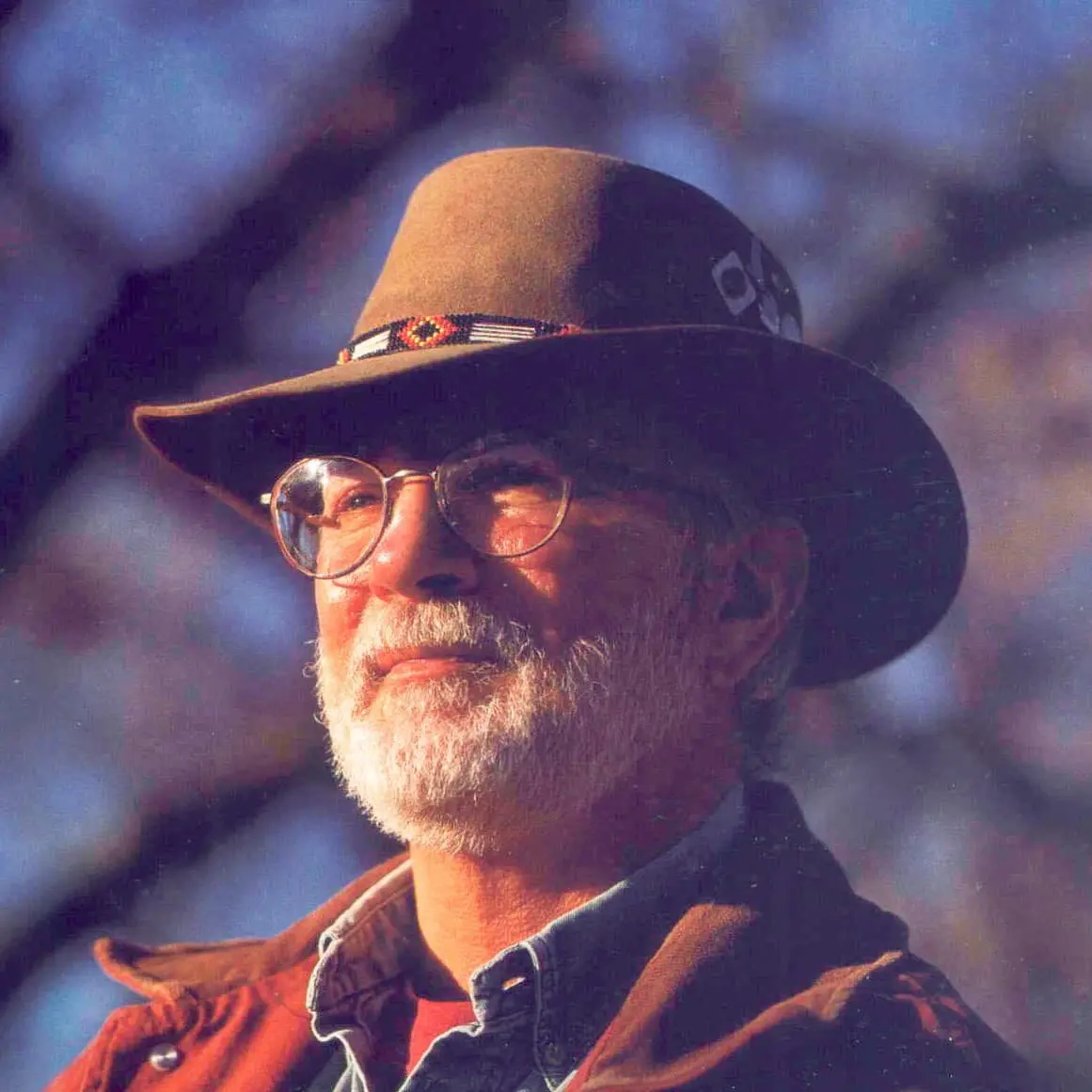

Another fascinating figure on the scene was Tom Hall, who stood out from the rest of us in his tweed coat and graying beard and played regularly at another Charles Street coffeehouse, The Loft. He knew everything there was to know about folk music, like a walking anthology of every traditional folk song there ever was, and his rendering of sea shanties were extremely popular. Hall started a tradition on Charles Street: celebrating poet Robert Burns’s birthday, which we did with fervor in parties that often lasted for days, during which Hall would “bore” us by reciting many of Burns’s long, contemplative verses from memory. Then there was Diane Gagner, a young girl who arrived to one of the hoots at the Stone accompanied by her parents and blew us all away with her amazing voice and style. Backed by Kenny Girard most of the time, she had no trouble navigating her 12-string Guild, which rang out in perfect tune with her lovely voice, and eventually became a songwriter. She appeared on a few sterling recordings with Paul MacNeil and her best-known tune is “Love Maybe.”

One afternoon, just days after he’d been discharged from the Navy, Chris Biggi walked into the Turks Head – still in uniform! – and said the music was so great that it should be recorded. Soon he began showing up at gigs with a Wollensak tape recorder, which was the start of my recording career and that of many others, and eventually Chris built a studio in his place on Mountfort Street in Kenmore Square, which was where some pretty serious recording took place. When I was recording my first album in 1972, Chris was the engineer and we worked together on the album concept and design. He continued recording and archiving for the rest of his life, building a big studio at his Hampton Falls, New Hampshire home along the way.

There were several other brights spot on Charles Street in the late ‘60s that weren’t coffeehouses, including Philip’s Drug Store on the corner of Cambridge Street, famous for cold, cold ice cream, and Harvard Gardens, an old-time bar where you could get a glass of beer for 10 cents and a shot for a quarter. And across from Philip’s was Buzzy’s Roast Beef, which served what many still consider to be the best roast beef sandwich on the planet.

Those of us who gigged along Charles Street were a world unto ourselves, usually ignored by those on the Cambridge folk scene but always highly acknowledged by our loyal fans on Beacon Hill. We all moved on to other areas eventually, but we always carried the dream and love of music with us. I, for one, moved north to Newburyport, Massachusetts, a small city that’s had a big music scene since at least the ‘30s, and a brand-new scene developed there that included Charles Street veterans Paul MacNeil, Kenny Girard, Diane Gagner and Chris Biggi, among others. I’m proud to be part of that scene, but most of all I’m proud that I was able to be part of the original one that took root and blossomed in the coffeehouses along Charles Street more than 60 years ago.

(by Bill Madison)