Cocoanut Grove

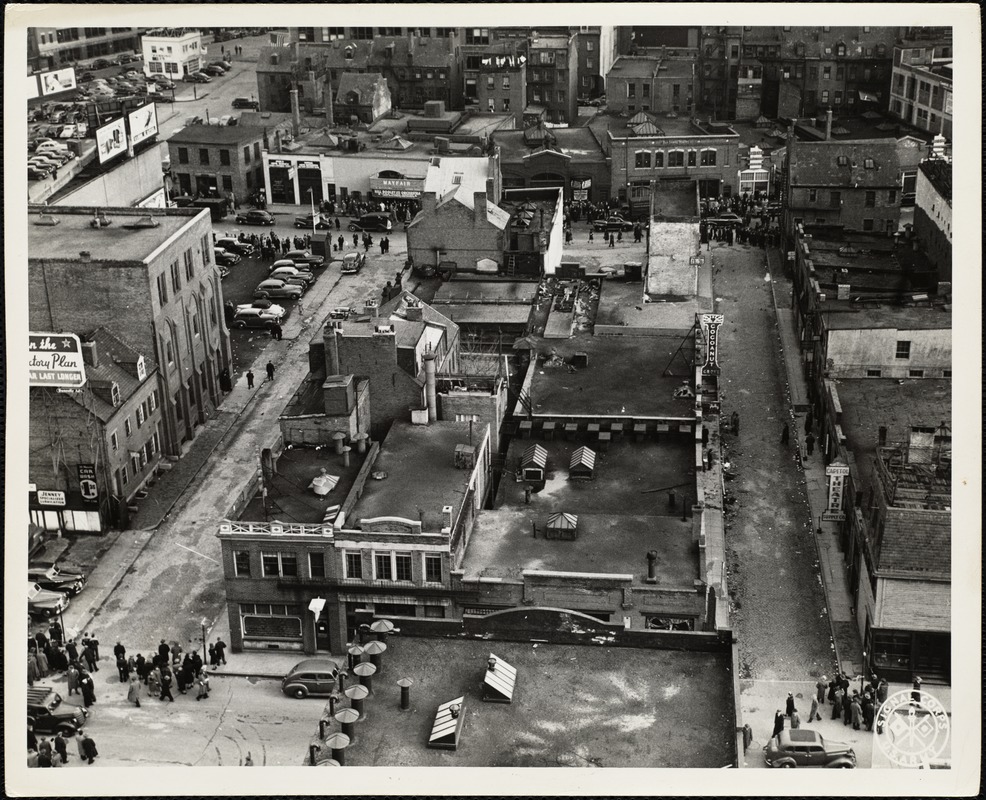

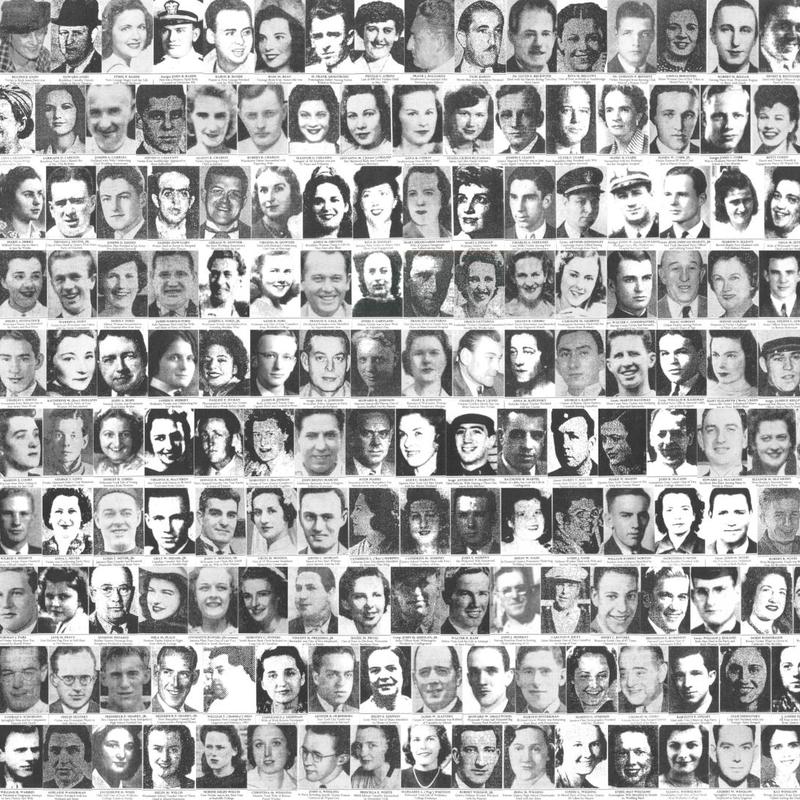

On November 28, 1942, as World War II engulfed Western Europe and the Asia-Pacific, something happened in Boston that dominated headlines throughout New England and across the world the next day, overshadowing the gruesome reports of horrific battles and escalating casualties: In the deadliest nightclub fire in US history, the Cocoanut Grove burned to the ground, killing 492 people.

And while that harrowing story has become well known over the decades, what’s less remembered is the club’s fascinating pre-inferno past. Before the blaze, it hosted the most illustrious musical acts of the era, including a suave 25-year old singing sensation named Frank Sinatra in 1941 – as part of Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra, before going solo in 1942 – and was equally known for its owners’ organized-crime connections as for its patrons’ influence, wealth and glamour.

OVERVIEW

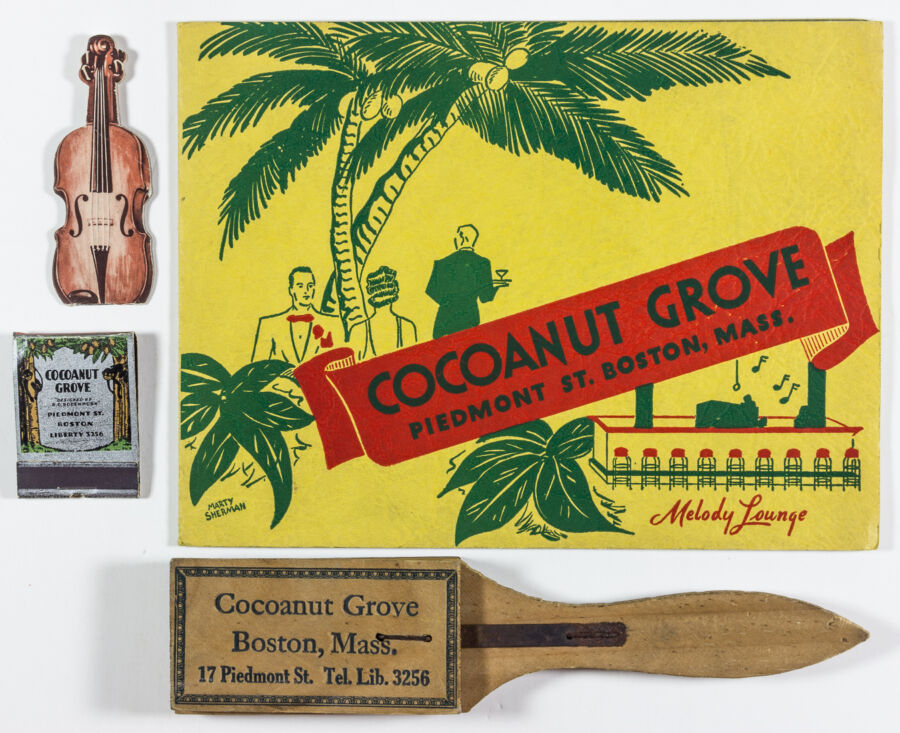

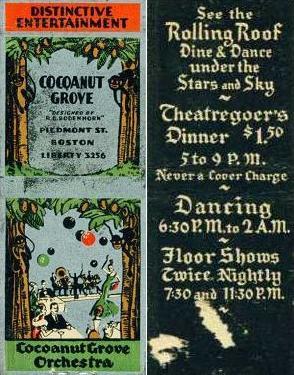

When it came to the most stylish, sophisticated, swingin’ spots in post-WWI, pre-WWII America, New York had the Copacabana, Los Angeles had the Café Trocadero, Chicago had the Club DeLisa and Boston had “the Grove,” as it was known. Extravagantly decorated with swanky furnishings, enormous artificial palm trees, Polynesian-style accoutrements and, of course, coconuts – plus a roll-open roof so patrons could “Dine & Dance under the Stars and Sky,” as the promo posters said – the venue was, for most of its 15-year existence, an uber-chic spot frequented by socialites, sports stars, military brass, vaudeville greats and Hollywood celebrities.

From 1931 to 1933, however, the Grove lost much of its original respectability by functioning as the de facto nighttime headquarters for Boston’s most infamous, feared and high-powered mobsters; the venue became their go-to place for wining, dining and otherwise bribing politicians and law-enforcement officials. By the late 1930s, the club’s reputation had been restored and it was hosting the most acclaimed bandleaders of the day, including Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, Sammy Kaye, Artie Shaw, Harry James, Claude Thornhill, Woody Herman, Buddy Clark, Frankie Carle and Les Brown, in addition to a regular rotation of lesser-known local, regional and national acts.

OPENING, ORIGINAL OWNERS LOCATION, INTERIOR

Opened on October 27, 1927 with a revolving door as its main entrance/exit – tragically, as it jammed during the fire due to the crush of panicked patrons – the Grove’s first owners were 23-year-old Mickey Alpert, a locally renowned crooner who’d appeared in theatre productions and on radio broadcasts, and nationally celebrated bandleader Jacques Renard, a 33-year old classically trained violinist born in modern-day Ukraine who moved to Boston as a child. Renard had often performed with his orchestras on top radio shows including George Burns’ and Gracie Allen’s and Eddie Cantor’s, and his 1925/’26 band occasionally included an ambitious 22-year old trombonist who became a household name in the ‘30s/’40s fronting his own orchestra: Glenn Miller.

Despite its prime location at 17 Piedmont Street near the Park Square theatre district, Prohibition made the club a risky commercial proposition. Still, Alpert and Renard were convinced that world-class live music would draw throngs of people to the 460-capacity, alcohol-free club and they adhered strictly to the national liquor ban. The Grove’s main area had a dining room, several small bars, a ballroom, a grand piano and a bandstand for jazz combos/singers. Big bands including the resident Cocoanut Grove Orchestra performed in the basement-level Melody Lounge which – as tragically as the club’s main egress being a revolving door – had only one exit, a four-foot-wide set of stairs leading to the foyer.

CHARLES “KING” SOLOMON, BARNETT “BARNEY WELANSKY

Initially, Alpert and Renard planned to finance the Grove through Jack Bennett, who used the pseudonym Jack Berman to conceal his checkered past, but they chose to fund it themselves after learning that Bennet was a well-known grifter who intended to launder money through the club. However, with Prohibition making it virtually impossible for the pair to turn a profit after all, Alpert and Renard sold the Grove to Charles “King” Solomon in 1931 for $10,000 (about $207,000 in 2024). Solomon, a nationally notorious, Russian-born mob boss who controlled nearly all of Boston’s and much of greater New England’s bootlegging, illegal narcotics and illicit gambling, operated the Grove as a speakeasy until January 1933, when a rival gang shot him dead in the men’s room of The Cotton Club on Tremont Street.

The third and final owner, Solomon’s heavily mob-connected lawyer Barnett “Barney” Welansky, transformed the Grove from an unsavory mob hangout back into the elegant retreat for the elite it had been from 1927 and 1931, hiring original co-owner Micky Alpert as full-time emcee. Ironically, given his well-publicized involvement with gangsters, he’d forged a close relationship with Boston Mayor Maurice Tobin over the years and spoke candidly about refusing to follow what he called “silly” building-code requirements and fire-escape regulations.

FIRE, SURVIVORS, FATALITIES, ARTHUR FIEDLER

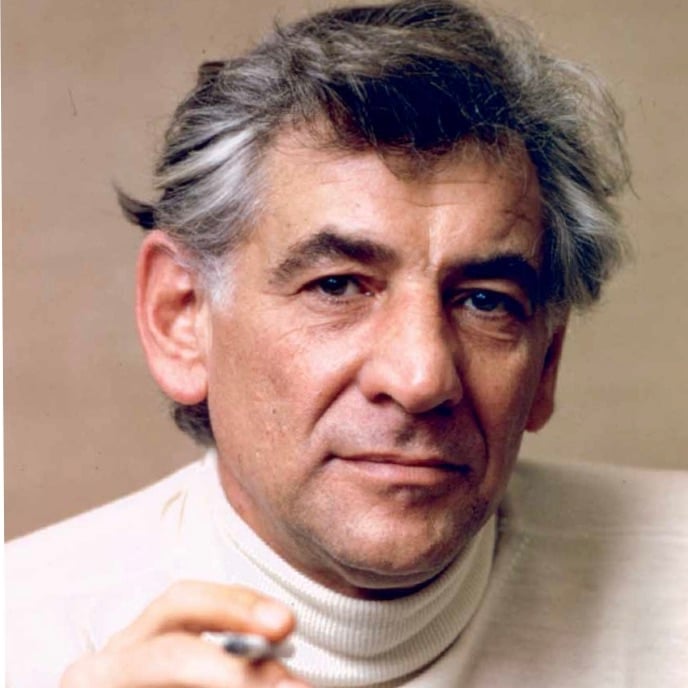

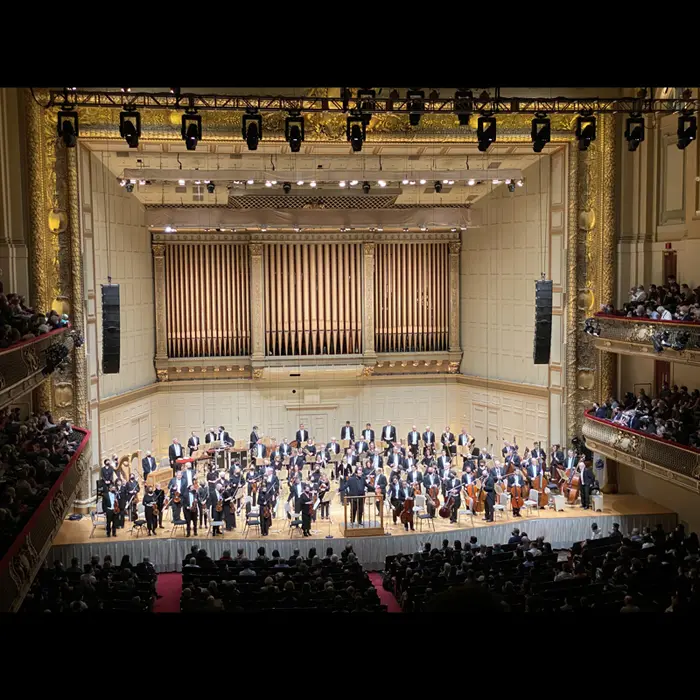

On the night of the five-alarm fire, when an estimated 1,000 people were in the club – more than double its official capacity – and six of its nine doors were locked, Alpert was singing onstage. He was backed by a band that included pianist Bernie Fazioli and bassist Jack Lesberg, a Boston native who survived after using his double-bass to smash open a wall, a breathtaking escape that Charles Mingus recounted in his autobiography Beneath the Underdog (Alfred A. Knopf, 1971). Lesberg went on to perform with jazz greats including Louis Armstrong, Earl Hines, Jack Teagarden, Sarah Vaughan and Benny Goodman and as part of the New York Symphony under the directorship of Lawrence, Massachusetts native Leonard Bernstein.

Alpert also survived, moving from Boston to New York City shortly afterward to establish a new career as a casting director. Fazioli did not make it out alive, however, along with several other band members and the Hollywood cowboy-movie star Buck Jones, who was in Boston as part of a national tour to sell war bonds. According to Arthur Fiedler’s official biography, Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1981, by former Boston Symphony Orchestra first violinist Harry Ellis Dickson), the then 48-year-old Boston Pops principal conductor assisted with rescue efforts at the scene of the fire.

WELANSKY’S CONVICTION/PARDON, RENARD’S POST-GROVE ACTIVITY

Welansky was convicted of 19 counts of negligent manslaughter for failure to secure the necessary building and alcohol permits and for allowing highly flammable materials and shoddy wiring in the Grove – among other things – and sentenced to between 12 and 15 years in prison. After serving just three and a half years, however, he was pardoned by the newly appointed Governor of Massachusetts, his good friend and former Boston Mayor Maurice Tobin.

After selling the Grove to Solomon in 1931, Renard enjoyed a successful career on stage and on the radio, making over 60 78-rpm recordings on the Victor label and becoming the musical director for CBS radio programs. He appeared in two Warner Brothers short-subject films alongside other established radio performers: Nick Kenny’s Radio Thrills No. 2 (with vocalist Arthur “The Street Singer” Tracy, violist and Boston native Leo Reisman, Native American jazz singer Mildred “The Queen of Swing” Bailey, British tenor Donald Novis and actor-singer Buddy “America’s Boy Friend” Rogers); and Rambling ‘Round Radio Row #5 (with vocal duo Reece & Dunn, comic trio The Funnyboners, country-western singer Sykes “Smith” Ballew, actress-singer Frances Langford and Arthur “The Street Singer” Tracy).

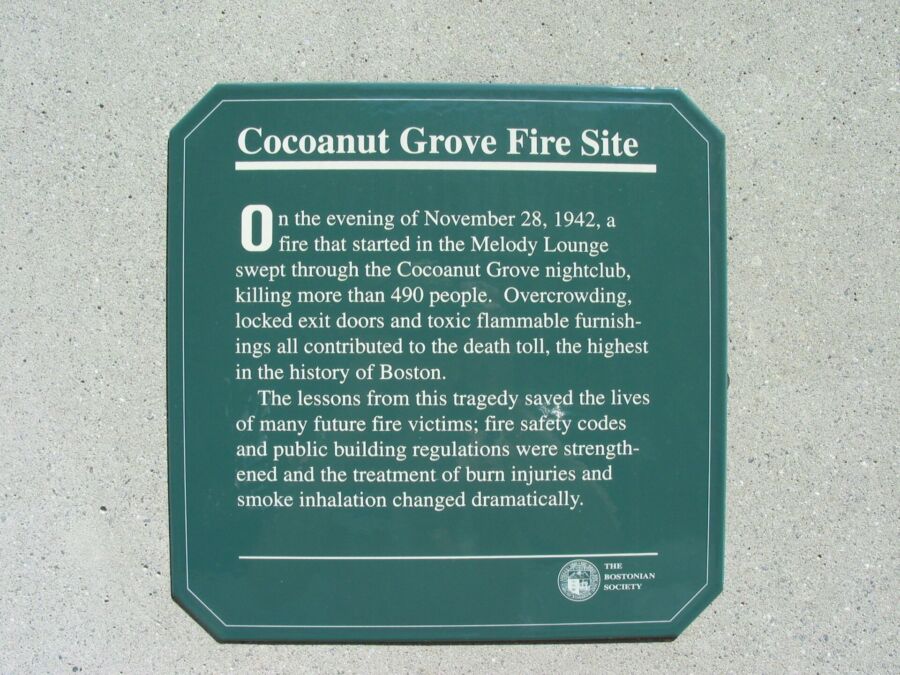

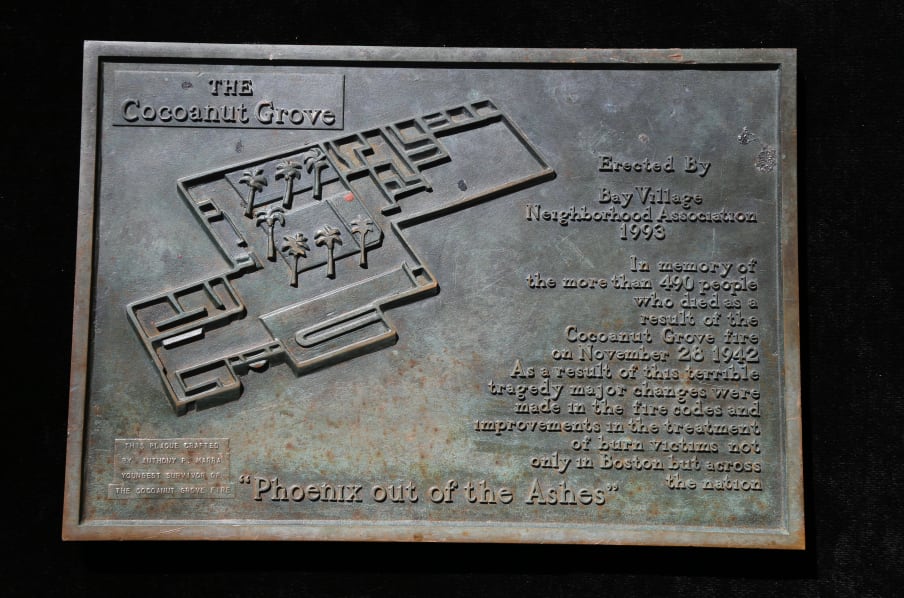

SIDEWALK PLAQUE, SIX LOCKED DOORS: THE LEGACY OF COCOANUT GROVE

In 1993, the Bay Village Association embedded a plaque in the sidewalk outside Cocoanut Grove’s former location which reads “In memory of the more than 490 people who died as a result of the Cocoanut Grove fire on November 28, 1942. As a result of that terrible tragedy major changes were made in the fire codes and improvements in the treatment of burn victims not only in Boston but across the nation. ‘Phoenix out of the Ashes.’”

In 2017, the 75th anniversary of the fire, WGBH aired the debut broadcast of the 70-minute documentary Six Locked Doors: The Legacy of Cocoanut Grove, which features archival footage, photographs and interviews with survivors, many in their 90s who had never spoken publicly about the event. The film, which also includes in-depth review and analysis of the incompetence, greed and corruption that led to the tragedy, won the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the 2020 Massachusetts Independent Film Festival.

Upon the documentary’s release, the Quincy, Massachusetts-based Fire Protection Research Foundation’s Executive Director Emeritus Casey Grant stressed its significance even decades after the disaster. “We are continually fighting complacency,” he told the Associated Press, citing the 2003 fire at The Station nightclub in West Warwick, Rhode Island that killed 100 people and the 2016 Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland, California that killed 36. “Films like this are hugely important to remind us about the lessons of history.”

(by D.S. Monahan)