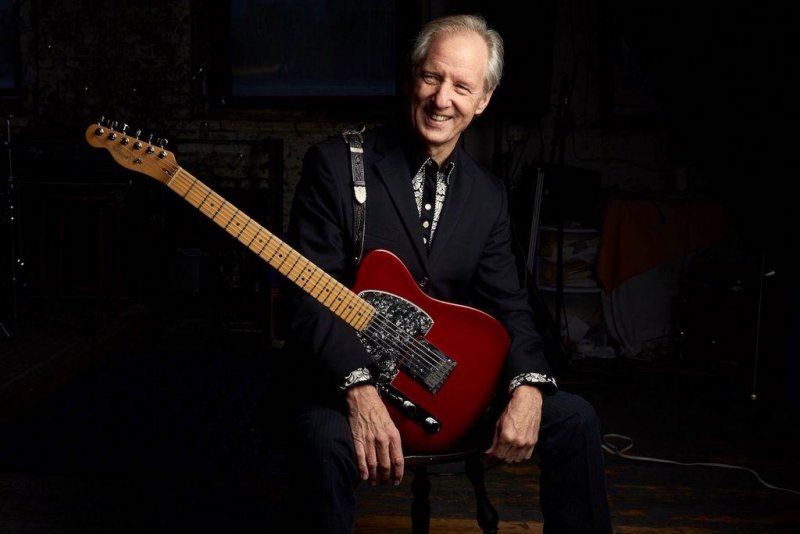

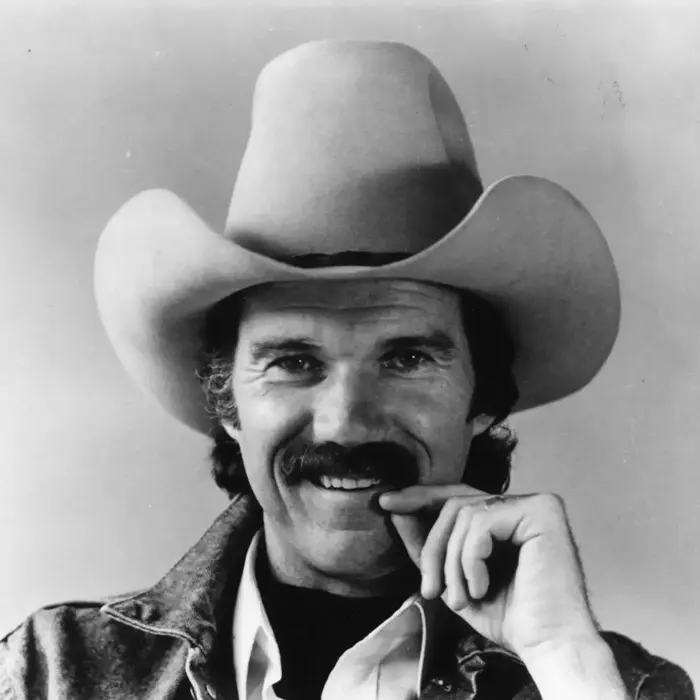

Chuck McDermott

It’s hard to imagine, but there was a time when people congregated at music clubs as one of the only ways to meet up and to meet other like-minded people. The city streets were packed, especially on the weekends, but even on weeknights, live music thrived, almost as a means of tribal identification.

In those years, Harvard Square still served Massachusetts as the unofficial headquarters of what was left of peace, love and freedom – and definitely of sex, drugs and rock and roll – and it was a neighborhood of tribal identification, too. The clubs were vibrant, whether at Charlie’s Place on Bow Street (where you might catch Springsteen), Jack’s on Mass Ave, or further afield at the Orson Welles Cinema. It was all happening. Palmer Street, off Brattle, was in the nexus of the Square and Jonathan Swift’s was right there directly across from the old Club 47, now Passim. You could count on a line at the door of Swifts, especially when Chuck McDermott and Wheatstraw were playing.

I remember the November night in ’74 when I was standing in line at Swifts, waiting to get in to see Chuck’s show. You could see your breath. Once we got through the door, I got stuck behind a pole – the only place left to stand. The place was slamming and Chuck was rocking. I’d heard of him and we shared an agent in Frank Neer, but this was the first time I’d ever seen him perform and I didn’t have the pleasure again for over 35 years. But more on that later.

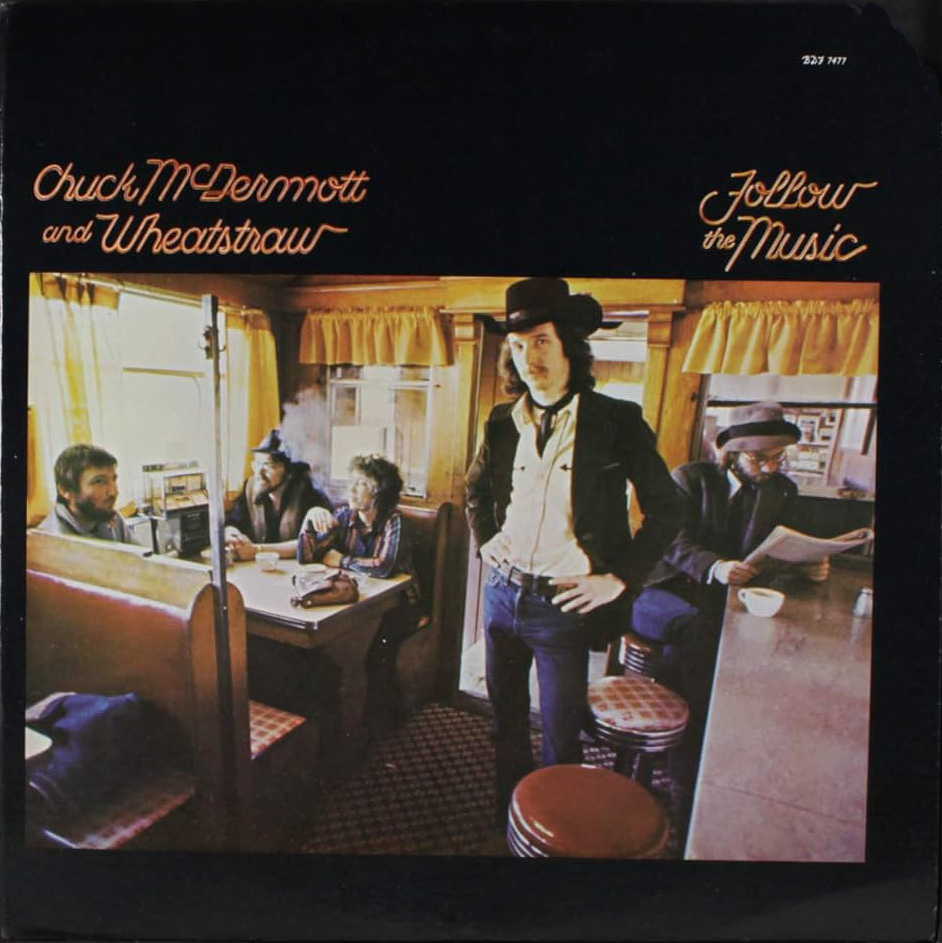

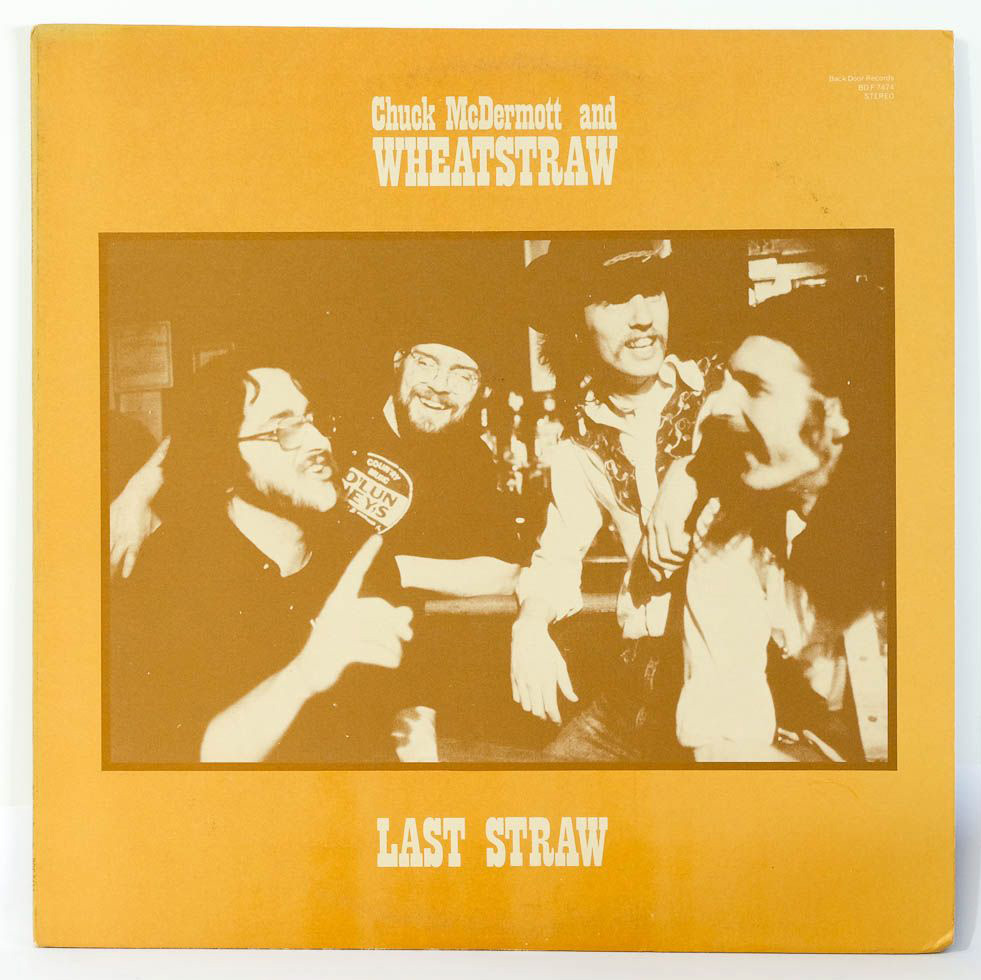

Everyone at Swifts saw that Chuck had brought something new to rock and roll: country music. Like fellow local John Lincoln Wright, he’d found a way to weave in his influences – Tammy Wynette, Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams – so that it wasn’t in-your-face country like the Merle Haggards of the time. It was rocked out like the Stones, or Poco, or The Byrds, so it was still “cool” to jam to, and jam we did, with many others, as Chuck and Wheatstraw developed a loyal and growing following of urban roots-rockers long before “Americana” was a musical category.

Wheatstraw continued to grow in the region and in New York, where they became an early favorite at the Lone Star Café, attracting the attention of writers like Rolling Stone critic Robert Christgau, among others. The band started opening for country acts like Ricky Skaggs and Asleep at the Wheel and, as their reputation grew, artists like Johnny and June Cash came to see them and Willie Nelson sat in. The Belushi brothers checked them out. Rolling Stone boosted their second album, comparing Chuck to Gram Parsons. Okay, now it’s all starting to make sense. And then the record business came calling with a development deal in Nashville that paired Chuck with an A-list band and the opportunity to move to LA as part of the package. So, off Chuck went for the big push and…boom! The same old music business story as countless others, meaning the financial bottom fell out of the label, leaving Chuck out there in LA with no Plan B.

But, as fate would have it, a call came from way out of left field. His old friend Joe Kennedy asked him to work on his uncle Ted’s presidential campaign, and of course that’s what he did for the next 10 months. This is an important part of Chuck’s story, as you will see.

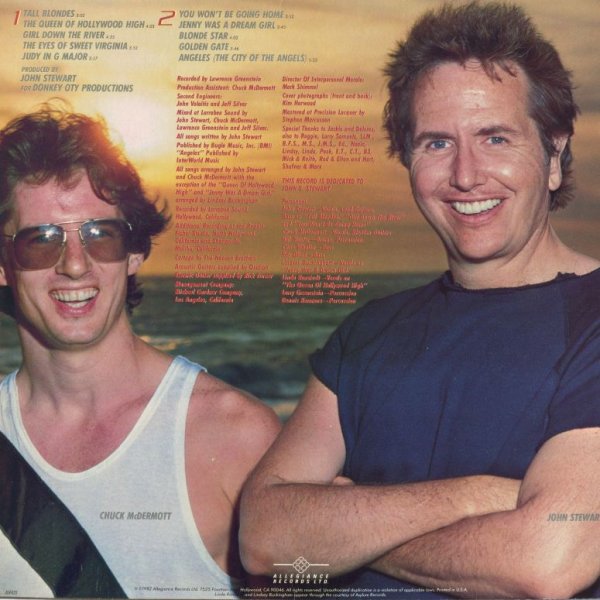

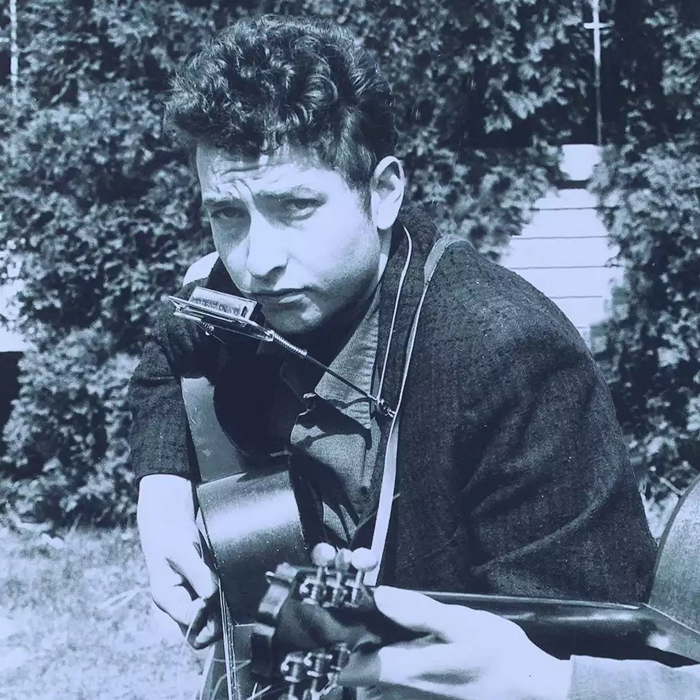

After the campaign, Chuck returned to LA, re-energized and became a favorite at the legendary Palomino Club. Elektra Records stepped up, recorded some demos and, in a twist of fate, one of Chuck’s early muses, John Stewart of The Kingston Trio, invited him to record some demos with him at Larrabee Studios for what then became a four-year working relationship, with John and Chuck working as a duo. This relationship elevated Chuck’s game since John brought artists like Linda Ronstadt, Bonnie Raitt, Lindsay Buckingham and Roger McGuinn into the mix. He was able to continue his solo career with an album completed at the famous Shangri-La studios in Malibu, and was able to find distribution on a UK label, but this was in 1984 and, once again, the times they were a-changin’.

By now, Chuck had become a father, and as he stared down his new responsibilities, Joe Kennedy called again with an offer to join him in a low-cost energy company that served the poor. Thus began a 25-plus year career in the environmental business for Chuck, which continued concurrently with regular gigs on the East and West coasts.

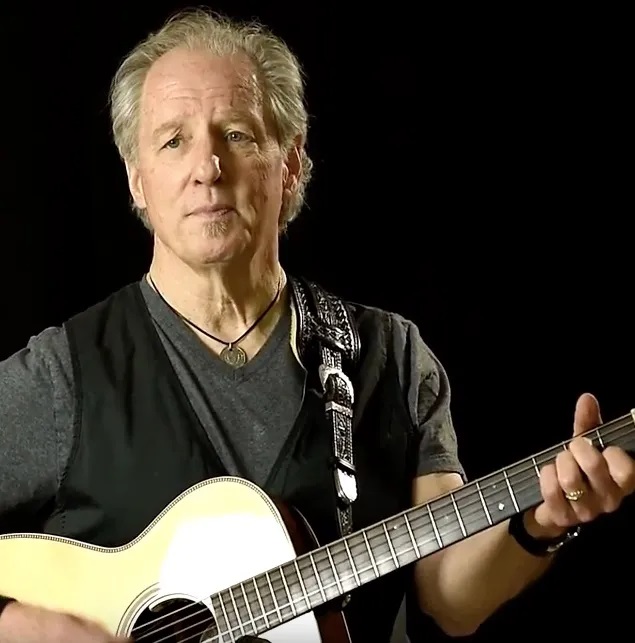

In 2012, our old mutual pal and agent Frank Neer engineered a meet-up and Chuck and I finally got to get to know one another on a personal level. Not only did we overlap in music, but I, too, had spent some time in the environmental business while on a musical hiatus, so now we joke about ourselves as “the only two musicians from Boston who were also in the garbage business.” As he moved away from his career in eco-friendly enterprise, he moved deeper once again into music. As it happened, this was occurring when Chuck and I met, so I got a birds-eye view of Chuck’s return to making music the center of his life, just as I had some years earlier.

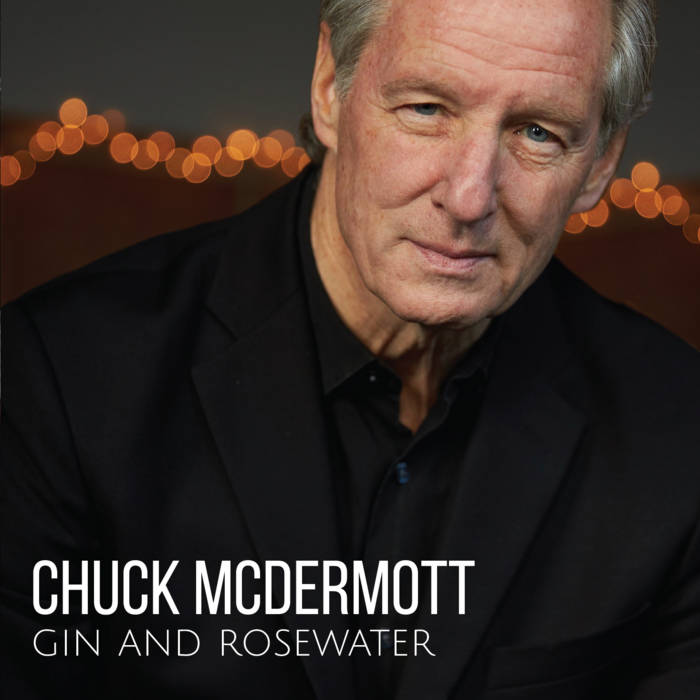

By now I had seen Chuck’s longtime (since the Palomino days!) West Coast ensemble on several occasions backing both Chuck and former Tower of Power singer and Malibu resident Lenny Goldsmith, which gave me a professional sense of just how good Chuck’s band was. And then I watched Chuck dive headlong into the Boston roots rock scene and emerge with some of the best players in the region, including guitar slingers Duke Levine (Bob Dylan) and Kevin Barry (Emmylou Harris), both of whom (along with a Steven Stills cameo) form the gritty center of Chuck’s first album in over 35 years, Gin and Rosewater.

Looking at Chuck through this 40-plus year lens has given me an appreciation for him as a visionary in both Americana music and the environment, which are related, in a very real way as treasures that need to be preserved. And Chuck continued his steadfast stewardship of these two treasures with a mighty new musical statement, Gin and Rosewater.

As one would expect from an authentic, real-deal American artist like Chuck, the centerpiece of the album is the powerful “Hold Back the Water,” a song about – you guessed it – rising sea levels and climate change. But before you smirk about “another protest song,” remember that this is Chuck’s actual experience and this experience is backed by the artist who pioneered American roots-rock with The Byrds, Gram Parsons and John Stewart. And, by the way, it features some of the best musicians in America. Timely? Yes. Contrived? No.

Life is beautiful and it’s beautiful to watch it unfold over time. That guy who I saw at Jonathan Swift’s from behind a pole in 1974 is now a father, an accomplished environmental pioneer and a journeyman singer-songwriter. He’s a legend. I hope you’ll grab a copy of Gin and Rosewater and check out a Chuck McDermott show sometime. He’s a friend of mine – and he’s one of Boston’s best.

(by John Cate)