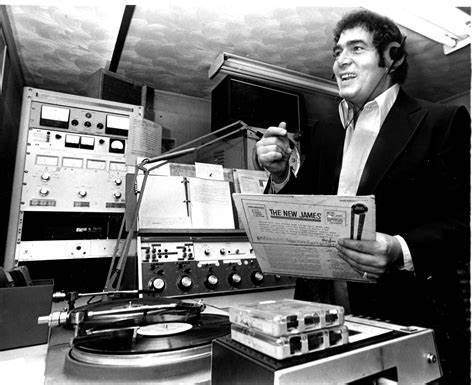

Bill Marlowe

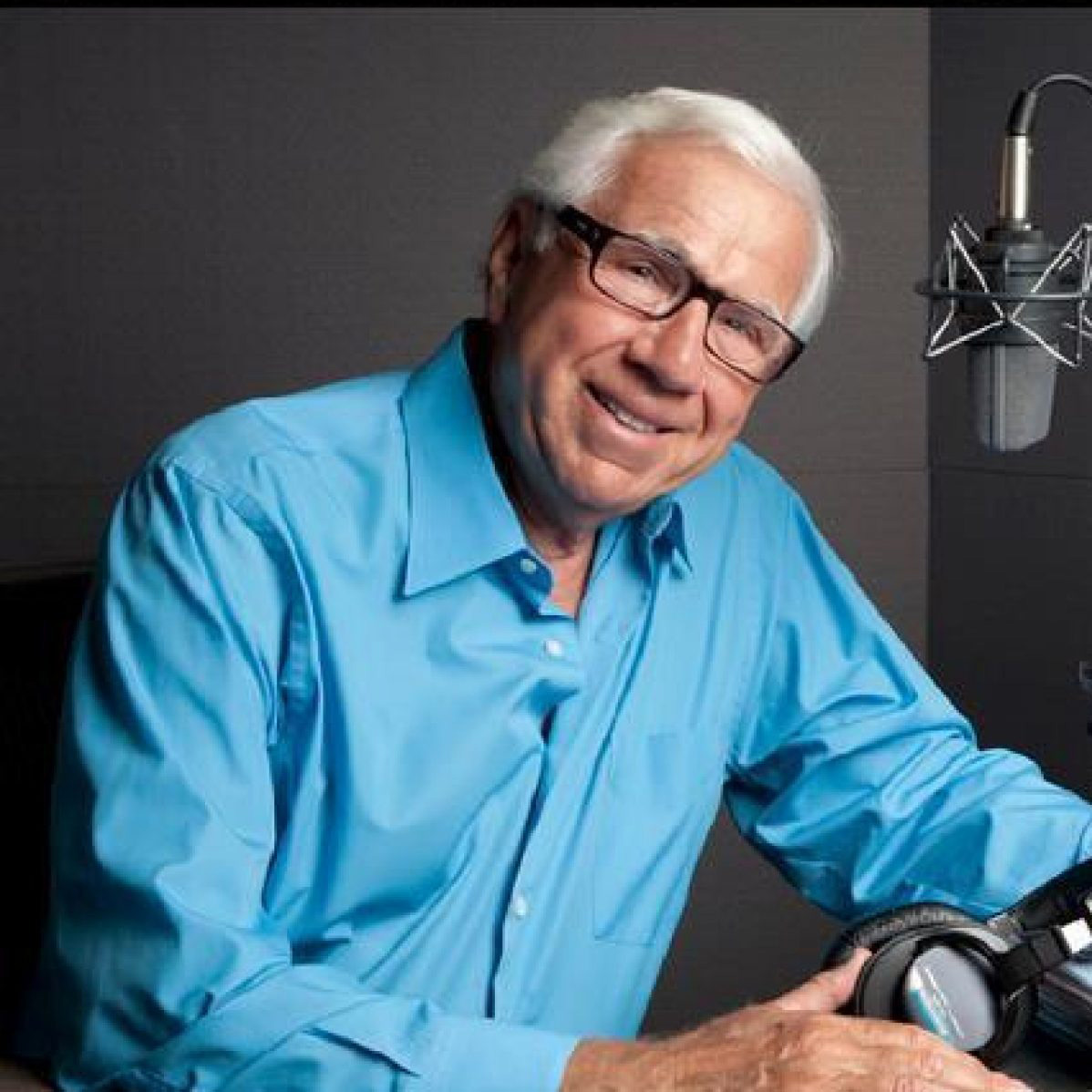

Bill Marlowe was known as “the announcer with the golden voice” and fans praised his exhaustive knowledge of jazz and big-band music. He knew many of the top names personally, including Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Mel Tormé, Tony Bennett, Buddy Greco and Sammy Davis Jr.; some of them visited him at his home when they were performing in Boston.

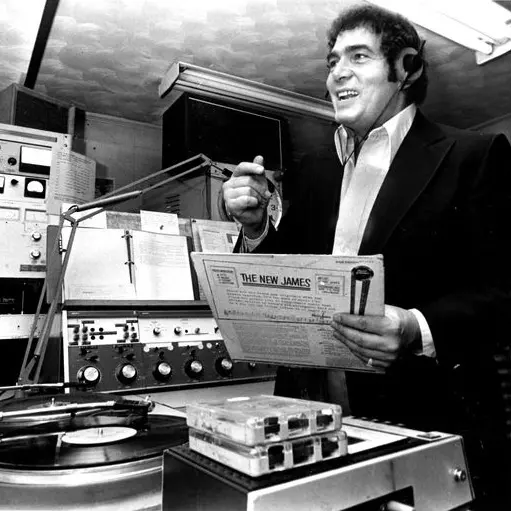

Marlowe began his career in late 1940s and during his four decades on the air, he saw firsthand how radio completely transformed. In the late ’40s and early ’50s, many stations still played the music he loved – jazz and pop standards. But rock ‘n’ roll began commandeering the charts in the mid-‘50s and mellifluous-voiced announcers were steadily replaced by fast-talking top-40 deejays who spun songs that Marlowe refused to play because he regarded the new genre as “noise.” As a result, fewer stations wanted to hire him as the years passed, but Marlowe persisted; he believed in what he was doing and he refused to compromise, even if that meant working at smaller stations and/or losing some of his prior fame. Throughout his career, he championed what he referred to as “good music” and remained an outspoken critic of rock ‘n’ roll, reminding his listeners at every opportunity that he played “M-U-S-I-C, not N-O-I-S-E.”

Radio beginnings, WCCM, WVOM, WBMS

Marlowe was born William Moglia, Jr. in Boston’s North End in August 1924 and grew up in nearby Medford. He appeared on the radio briefly at age nine, he once said, when he recited the soliloquy from “Hamlet” on Boston’s WEEI, and he listened to the radio constantly in high school. In 1944, he enrolled at Emerson College and completed a two-year program called “Special Courses in Radio,” according to Emerson’s archives.

By the summer of 1947, he’d landed his first full-time on-air gig at WCCM in Lawrence, Massachusetts. While there, he began using the on-air handle “Bill Marlowe,” since ethnic-sounding names of any kind, including Moglia, were discouraged at the time. Gradually, his career took off. Between 1948 and mid-1953, he worked at WCCM, WVOM (“the voice of Massachusetts”) in Brookline and WBMS in Boston. In June 1954, he started at Boston’s WCOP where, despite his love of jazz and big-band records, he was a top-40 deejay and had to play rock and R&B.

Record hops, Other live appearances

While at WCOP, Marlowe often hosted record hops and appeared at local events. On one such occasion, a carnival held by MIT in March 1956 at which Marlowe was the emcee, both he and rock ‘n’ roll itself received some terrible press. The event included games, contests and performances by well-known bands to raise money for a few educational charities, but an unexpectedly large crowd showed up and didn’t want to just watch the show; they assumed it was a record hop and wanted to dance, too. When they were told that the venue wasn’t equipped for dancing, pushing and shoving ensued, fights broke out and the show had to be stopped. The police were called in to restore order, at least one person was arrested and another was hospitalized. One officer on the scene blamed rock ‘n’ roll for the violent outbreak – the genre attracted “troublemakers,” he said – and the mayor of Cambridge said he would ban Marlowe from all future record hops in the city.

Most of Marlowe’s live appearances were without incident, however, and he became one of Boston’s most popular deejays. Years later, he expressed regret that he’d played any top-40 at all, though few (if any) listeners realized at the time how much he despised the music he was directed to put on the air. Very cleverly, sometimes he found a way to work in a song or two that he did like.

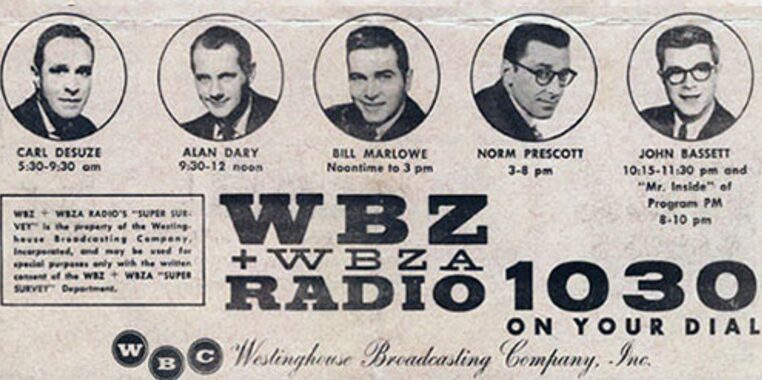

WBZ Years, Payola, Promoting future stars

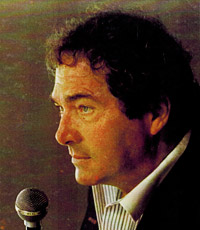

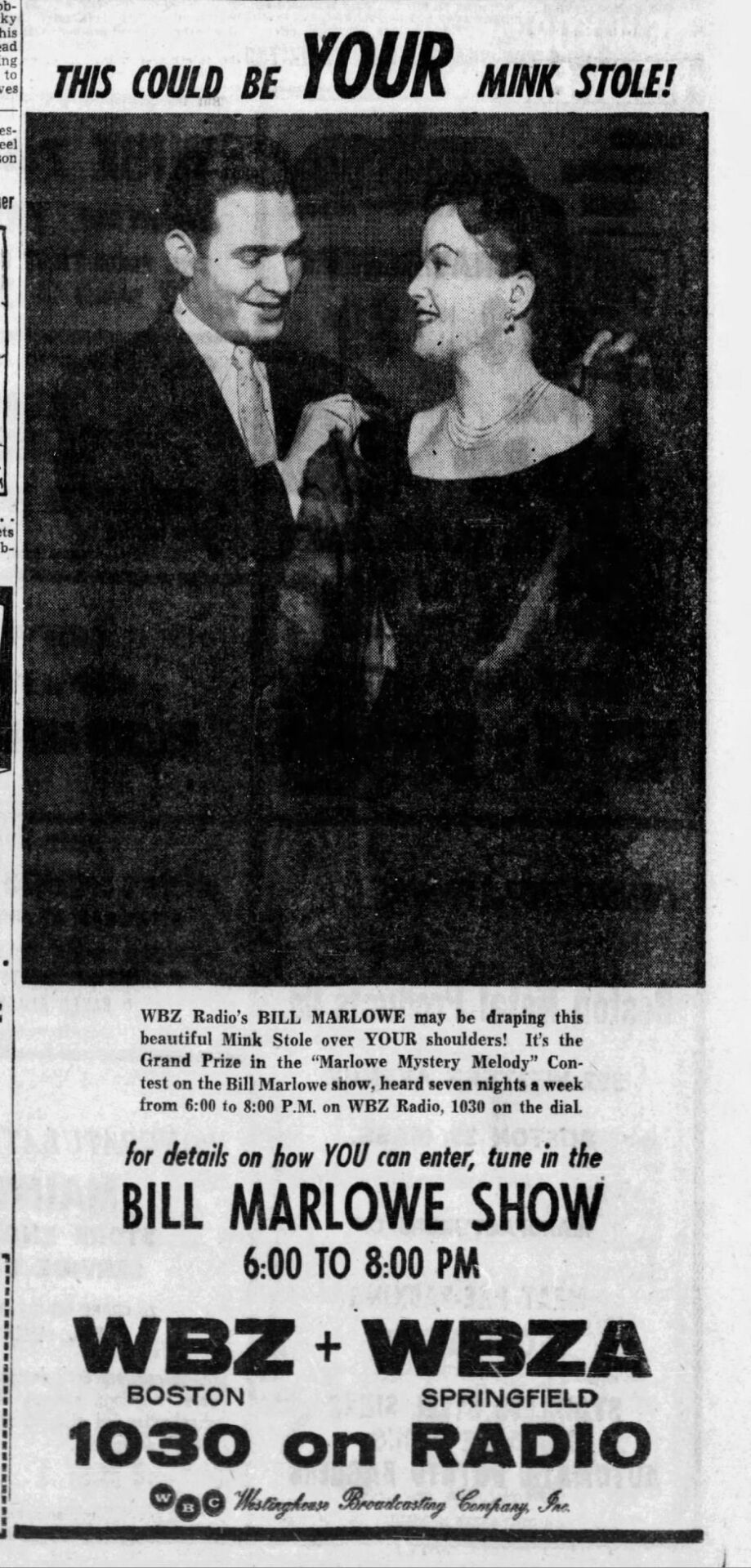

Marlowe continued that practice after leaving WCOP in March 1957 to join WBZ, which had a 50,000-watt signal that gave it the furthest reach of any station in the Northeast. While he played the hit records on the station’s playlist, he also aired “good music” like Carmen McRae, Lester Lanin and George Shearing, which earned him heaps of praise from newspaper columnist Bill Buchanan, who covered the Boston media scene and shared Marlowe’s distain for rock ‘n’ roll. In April 1958, Buchanan wrote that Marlowe had “done more to promote good pop and jazz music than any other disc jockey [in Boston]” since “he plays more jazz records a week than any other disc jockey and he’s respected by the artists themselves.”

And Buchanan was not exaggerating. Marlowe was totally plugged in to the Boston nightclub scene, often serving as an emcee and inviting artists to appear on his radio program. No matter where he worked in the late ‘50s, he was one of Boston’s top-rated deejays, and when he liked an artist’s work, he gave it maximum exposure. It was the payola era (when many deejays took bribes in return for airplay), but Marlowe insisted that he never took a single dime. Rather, he said, he genuinely thought certain artists were more talented than others and believed that the public should hear them.

Marlow helped numerous artists to gain greater prominence, among them Erroll Garner (whom he nicknamed “The Elf”), Dakota Staton, Bobby Short and Stan Kenton. Many of those he supported were quick to express their appreciation in public; local jazz pianist Al Vega recorded a song called “Marlowe’s Mood” in 1957 and Stan Kenton thanked Marlowe during a concert in Lynn in 1958. Years after iconic cabaret singer-pianist Bobby Short had a huge hit with “Sand in My Shoes,” he told reporters that the song succeeded in Boston largely because Marlowe put it into heavy rotation.

WILD, WNAC, WNAC-TV, move to New York, Return to Boston

In December 1958, Marlowe left WBZ and joined WILD where, along with playing current hits, he devoted several hours on Sundays to Frank Sinatra’s songs. In December 1959, he joined WNAC (now WRKO), which aired a pop-standards format that allowed him to play some jazz. In addition to his radio roles, he hosted a television show featuring hit movies, Hollywood’s Greatest Stars, on WNAC-TV in 1959, but that wasn’t his first time as a TV personality. In early 1958, he hosted Storyville, a short-lived jazz series on WBZ-TV; among the guests were Bobby Hackett and His Sextet, Sarah Vaughan, Jonah Jones and Abby Lincoln.In 1968, he narrated a TV documentary about Stan Kenton, Bound to Be Heard.

In the spring of 1965, Marlowe left WNAC and moved to New York City, where he worked at WCBS and WHN but – in what he later acknowledged had been a recurring theme – he had frequent disagreements with the stations’ program directors over musical direction, since he wanted to play the music he loved, not top-40 hits. After three years in the Big Apple, he returned to greater Boston. He hosted a film series on Channel 56 and, in March 1968, joined WNTN in Newton, a new station where he was allowed to play the “good music” that he loved. He continued to emcee concerts, including one in April 1968 at Boston’s Symphony Hall featuring Stan Kenton, June Christy and The Four Freshmen.

Marlow left WNTN after about a year and was off the air for several years after that, explaining later that he’d become disenchanted with the radio business and needed some time away. In 1973, he returned to the air on Lynn’s WLYN, where he could play “good music,” and he moved from there to WHET in Waltham (formerly WCRB) in March 1976. In July 1978, after the owners changed the format, he returned to WNTN, and in 1983 he moved to WMRE (formerly WMEX). While there, he had a regular weekday spot and hosted the Sunday program Strictly Sinatra.

Health issues, Final years

By 1986, Marlowe was struggling with major health issues, having been diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a disease that was affecting his vision. Although it was incurable, he responded well to medication and worked briefly at WXKS-AM, and then, through the early ‘90s, at WRCA, where he hosted his Sinatra show. By that time, he’d become the well-known voice in radio and television commercials for Giant Glass and Tommy Floramo’s restaurant in Chelsea (“Where the meat falls off the bone!”).

Bill Marlowe, who loved “good music” and fought tooth and nail over the decades for his right to play it, died of cancer in July 1996 at age 71. Among the Boston broadcasters who cited him as an influence was Ron Della Chiesa, who began hosting his own Sinatra program in January 1997. Throughout his career, Marlowe remained a passionate voice for jazz and pop standards and, as anyone who ever listened to him knows, he was a lifelong proponent of “M-U-S-I-C, not N-O-I-S-E.”

(by Donna Halper)

Former deejay, music director and radio consultant Donna Halper is a Boston-based historian who has spent over three decades as a professor, teaching media-related courses at Emerson College, the University of Massachusetts and Lesley University. She’s the author of six books including Boston Radio: 1920-2010 (Arcadia Publishing, 2011) and has written articles for a variety of publications. Dr. Halper was inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2023.