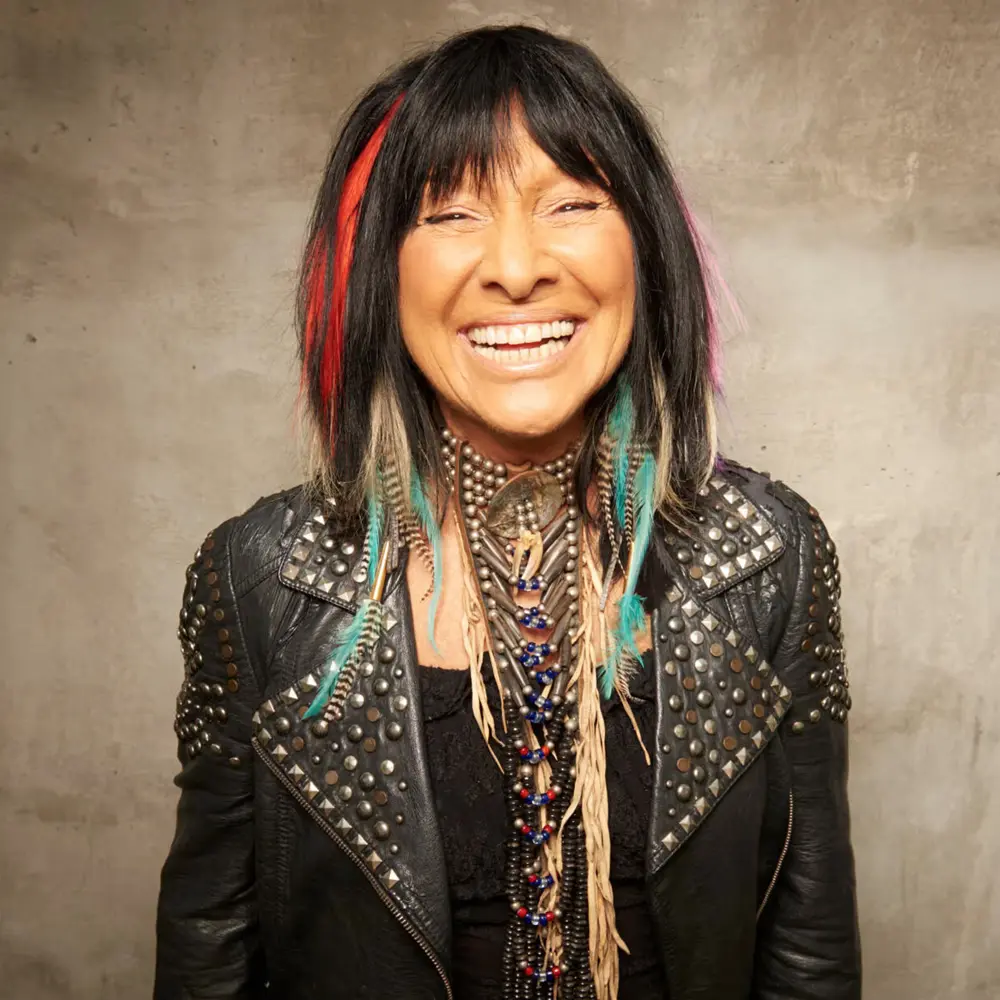

Betsy Siggins

It’s hard to think of another non-musician who was quite as entrenched in the thriving ‘60s folk scene in Cambridge, Massachusetts as Betsy Siggins was. It’s equally difficult to name someone who’s spent their entire adult life upholding the scene’s ideals and making tireless efforts to preserve its legacy, but that’s precisely what Siggins has done as evidenced by her decades of volunteerism, activism and documentation. If one wanted to bestow her with some snappy new nickname, “Cambridge’s First Lady of Folk” would suit as well as “Boston’s First Lady of Jazz” suited Rebecca Parris.

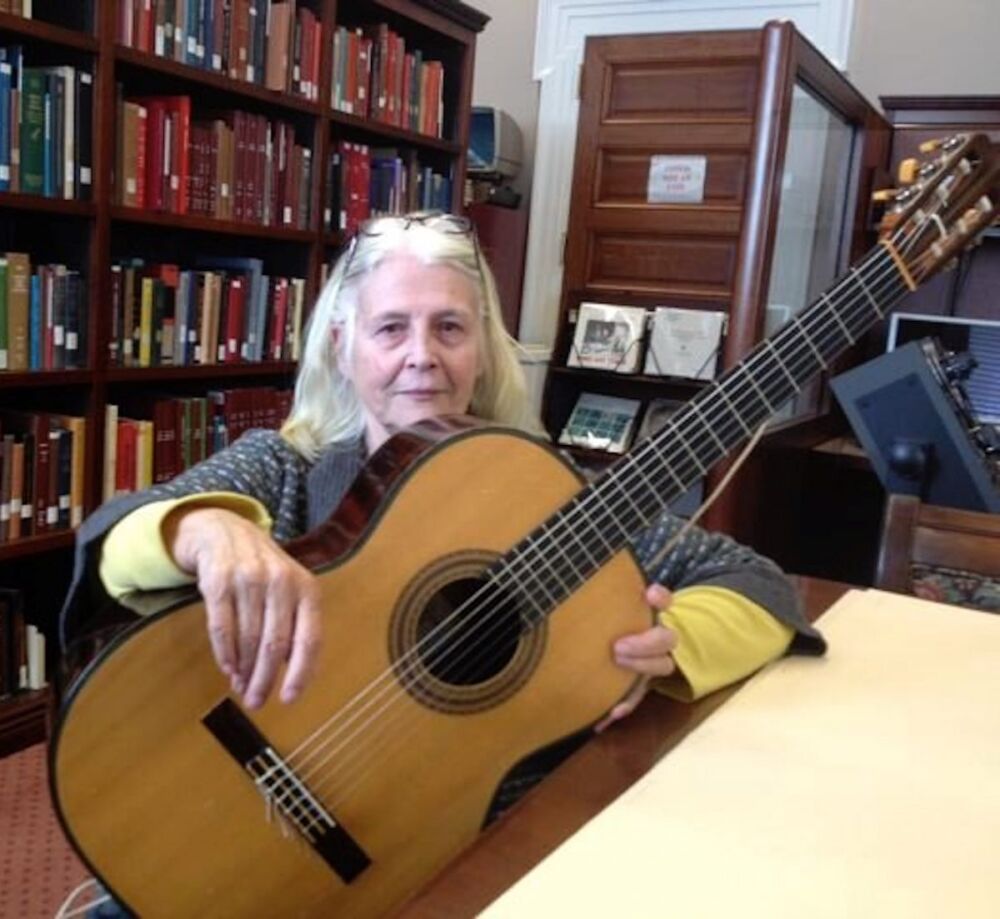

After working as the scheduler at Club 47 for most of the ‘60s, organizing festivals and benefit concerts in the ‘70s and ‘80s and being executive director of the Passim Folk Music and Cultural Center from ‘97 to ‘09, she founded Folk New England and spearheaded the curation of the New England Folk Music Archives, both of which she continues to oversee today. And if you think that sounds like an awful lot for an octogenarian to manage, then clearly you haven’t met the likes of Besty Siggins.

EARLY YEARS, MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

Born Betsy Minot on October 1, 1939 to Francis Minot and Ellen Le Maine, Siggins grew up in Cotuit, Massachusetts, a village that’s part of Barnstable on Cape Cod, with her half-sister Agnes, half-brother Francis and adopted sister Muriel. Siggins’s family has deep, rather prestigious ties to New England: her great-grandfather was a member of to the Massachusetts legislature and served as US attorney general and US secretary of state; her grandfather was professor of medicine at Harvard and a physician at Boston City Hospital; and her father was an MIT graduate, engineer, ship designer and oceanographer and founded the Ocean Resources Institute of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Her biological mother left the family when she was very young and her stepmother, Bernice Dubb Jackson, was a concert pianist, so Siggins was exposed to a wide range of classical music. Her own musical tastes, however, leaned more toward Grand Ole Opry than Symphony Hall. “She practiced piano before I went to school, from six to seven in the morning doing scales downstairs, playing a lot of Beethoven and Chopin,” Siggins said in a 2012 interview with Katrina Morse published in Music in Cambridge. “Upstairs, on my forbidden radio, after nine o’clock at night, under the covers, when the airwaves were so clean that we got WWVA from Wheeling, West Virginia, I would listen to country and western music from the ‘50s, and then I would hear her playing a very different kind of music. When I look back on it, those were the bookends for me. I never strayed, really.”

In the spring of 1958, Siggins graduated from Cherry Lawn School, a boarding school in Darien, Connecticut that closed in 1972. She and her friends took occasional weekend trips to Greenwich Village which, along with Cambridge, was a folk mecca at the time, and she tried her hand at playing an instrument when she was in her mid-teens. “I played the accordion, but probably quite badly, for about two years in high school,” she told Morse. “But the wonderful thing about where I was then is that it either influenced you and you moved closer to it, or it didn’t influence you and you put it on the back burner.”

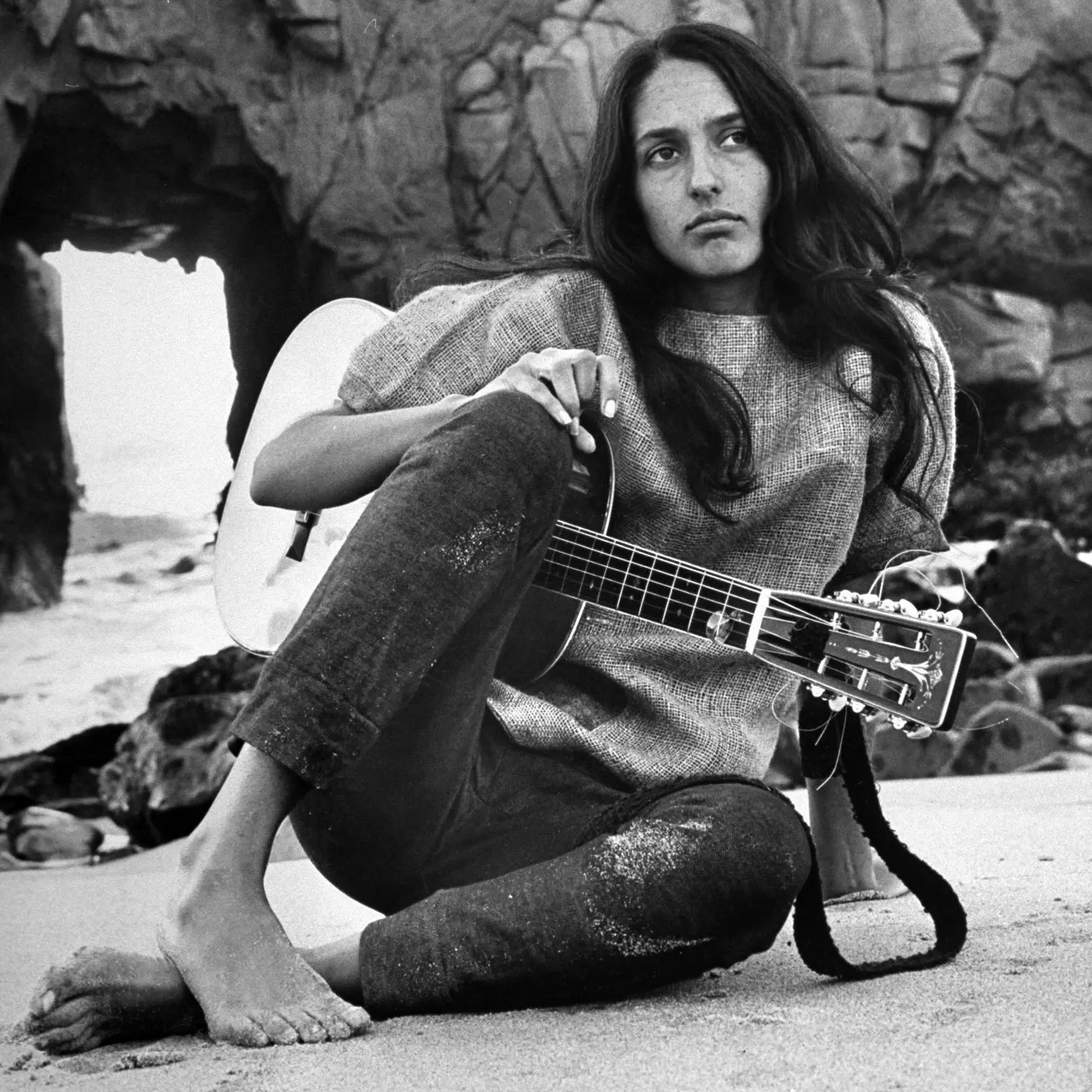

BOSTON UNIVERSITY, BOB SIGGINS, CLUB MOUNT AUBURN 47

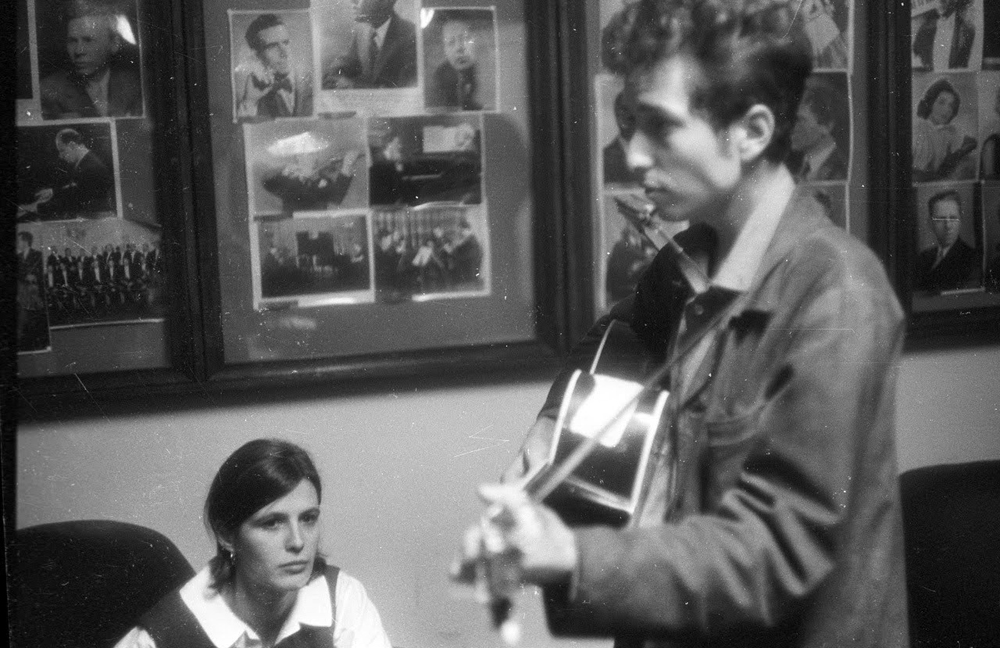

In the fall of 1958, Siggins enrolled at Boston University, quickly becoming part of the burgeoning folk community in Boston and Cambridge along with her newfound friend Joan Baez, a fellow BU student. “Joan and I were in the same class together and that proved to be both the best thing that happened to me and the worst thing that happened to me because it wasn’t long before we gave up academics for the folk, Bohemian lifestyle,“ she told Morse. Both dropped out of BU during the first semester of their freshman year, becoming full-time participants in the protest culture that was bubbling up in the area. “[Protesting] was probably the touchstone for many of us,” she told Morse. “We discovered that people could indeed protest in a safe environment. They could say what they felt about war and civil rights and women’s rights.”

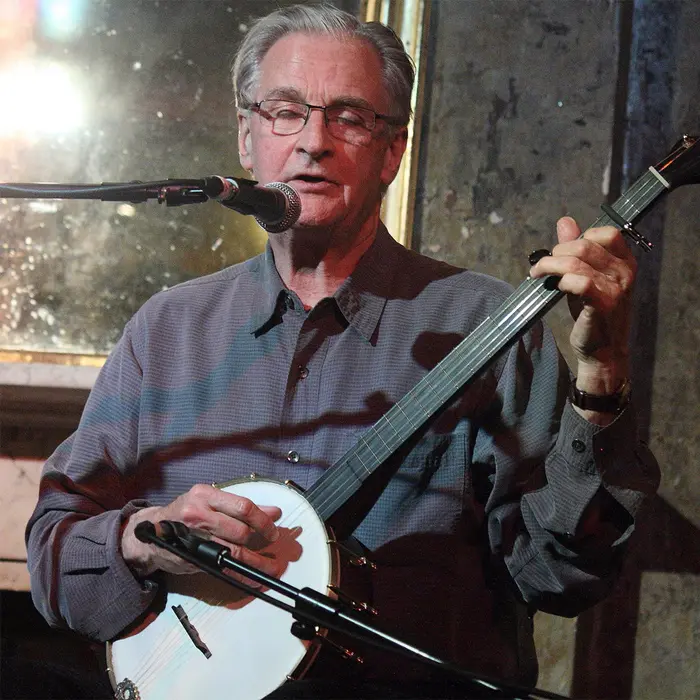

In 1961, Siggins married Bob Siggins, a Harvard graduate who played banjo and sang in The Charles River Valley Boys. Later that year, the pair joined the board of directors at Club Mount Auburn 47, which opened as a jazz venue in 1958 but had been closed for several months and was reopening under new management as a folk space. Structured as a nonprofit, the club invited certain members of the folk community to join the board, so the newlyweds fit the bill perfectly. Betsy immediately began working at the venue full time in various capacities – in the kitchen, waitressing, managing the club’s art gallery – before becoming its schedule arranger, with Jim Rooney or Byron Linardos booking the talent.

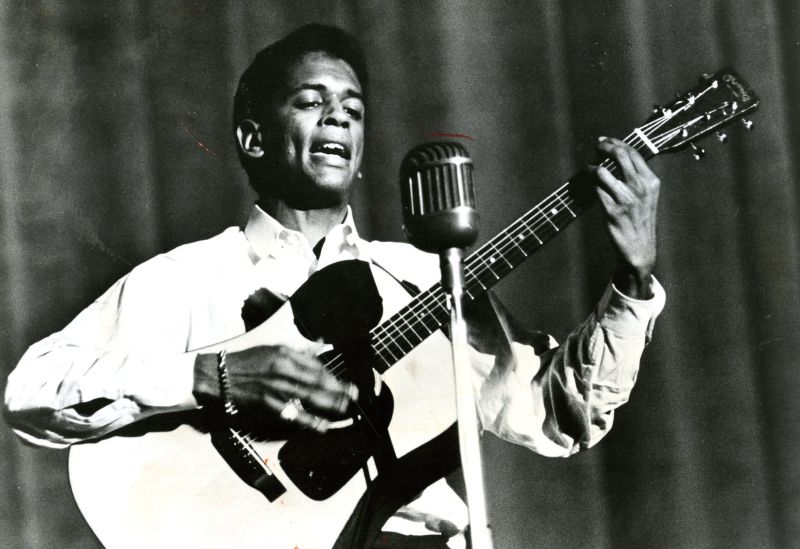

Within weeks, Club Mount Auburn 47 became Cambridge’s leading folk club, becoming a career launching pad for artists from New England and beyond and a place where many of the predominantly white patrons saw African-Americans performing folk and folk-blues for the first time. Siggins has called the venue “seminal” and the era “a magical time,” but she told Morse that staying in the black was a constant struggle and that not everyone was supportive. “We had no lease, we had no fundraising abilities and we’d never even thought about fundraising,” she said. “It cost a dollar to get in and we wondered why we were slipping into debt. And we had a landlady who was just ugly. She would come by screaming in the windows, ‘I’m sick and tired of all these hippies hanging around my place! It looks disgusting!’ The cops hated us, too, because, of course, our music was ‘communist’ and we were ‘plotting the overthrow of America.’”

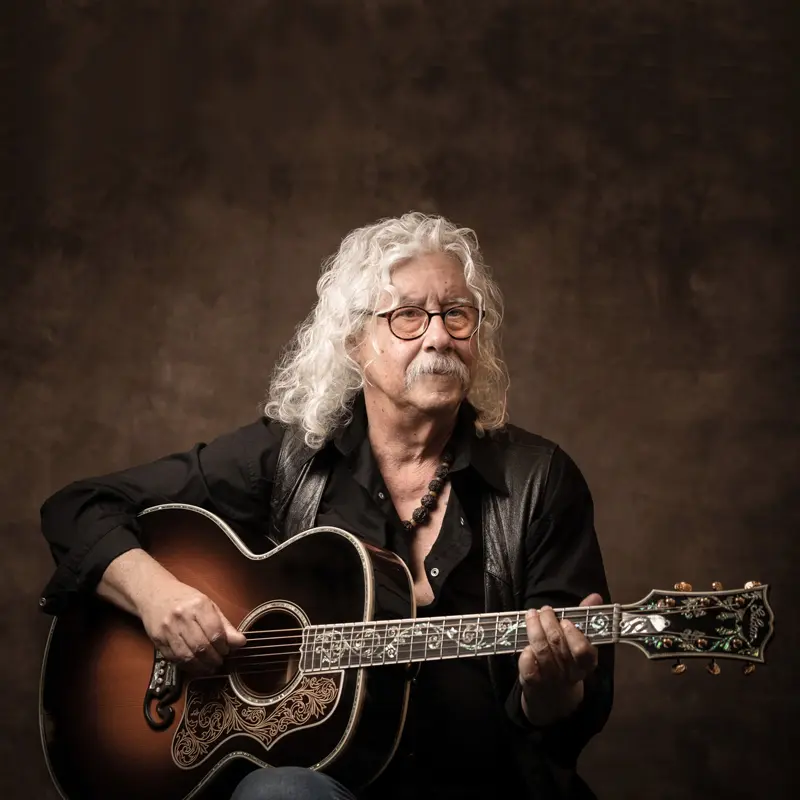

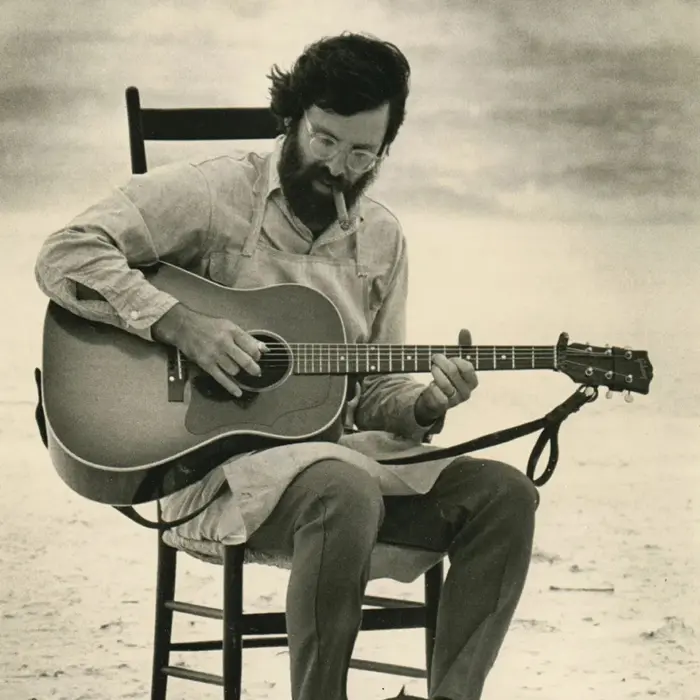

During Siggins’s seven years at the club, which was renamed Club 47 in 1963 after moving from 47 Mount Auburn Street to 47 Palmer Street in Cambridge, she witnessed noteworthy events such as 21-year-old Bob Dylan’s first official show at the venue (in April 1963) and bluesman Son House’s first gig in over two decades (in July 1964). Among the New England-rooted acts that appeared were Baez, Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band, Arlo Guthrie, Eric von Schmidt, Jackie Washington, Geoff Muldaur, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Tom Rush, Mitch Greenhill, Chris Smither, Taj Mahal, Peter Rowan and The Charles River Valley Boys. Others included Pete Seeger, Judy Collins, Joni Mitchell, Mississippi John Hurt, “Spider” John Koerner, Howlin’ Wolf, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Buddy Guy, The Staple Singers, Muddy Waters, Junior Wells, Bill Monroe & The Bluegrass Boys, John Lee Hooker, Gordon Lightfoot, Doc Watson, Reverend Gary Davis, Richie Havens, The Chambers Brothers, Rosalie Sorrells, John Hammond and Mose Alison. Siggins and music journalist Robert Shelton of The New York Times corresponded frequently, with Siggins sending him updates on the Cambridge scene.

CLUB 47 CLOSING, LESSONS LEARNED

In 1968, by which time psychedelia had begun replacing folk as the genre du jour, Club 47 closed. After a brief stint as a bookstore-cum-gallery named Passim owned by Walter and Renee Juda, the ownership changed again, with new proprietors Bob and Rae Ann Donlin turning it back into a live-music venue, also called Passim, which it remains to this day. Asked why she thinks the club didn’t last any longer than it did, Siggins said there were several reasons. “The failing of Club 47 began because the blues guys all wanted to play in bars because that’s what they were used to, and they also wanted to drink when they could, and we didn’t have a liquor license,” she told Morse. “We didn’t even think of a liquor license; it was the pureness of not mixing liquor with music. But slowly it became like there was more money for those guys to make in a bar scene, and that was terribly important to them. Since the crowd was calling for it, there was no reason for them not to do it. So we kind of lost our place as a regular blues place.”

In addition to the booze factor, Siggins has cited other problems as the clubs’ inability to pay enough to draw duos, trios and bigger bands, largely due to the management’s naivete regarding the importance of charging an entrance fee of more than a dollar. “We were kind of short-sighted about the entrance fee, and that’s just because we were new and it was new and nobody except bars had cover charges. People bought coffee but the coffee cost only about twenty five cents,” she told Morse, adding only half-jokingly that she doesn’t think the Cambridge powers that were would have granted the club a liquor license even if they’d applied for one since “they thought we were ‘communists’ and that we would riot.”

LEAVING/RETURNING TO CAMBRIDGE, ACCOLADES, AWARDS, MEMOIR

After Club 47 shuttered in 1968, Siggins relocated to Washington, DC, where she worked on various music-related events including the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife. In 1979, she moved to New York City, remaining there for some 18 years, earning a BS in community service, founding programs and organizing benefit concerts to help people with AIDS and volunteering at soup kitchens and food pantries. In 1997, she returned to Cambridge spending the next dozen years as executive director of the Passim Folk Music and Cultural Center. During her tenure, she oversaw the opening of Passim School of Music and the creation of the Passim Archives while developing nonprofit programs such as Culture for Kids, designed for underserved students in the Cambridge school system. Since leaving Passim in 2009, she’s founded Folk New England, the stated mission of which is, in part, “to foster appreciation and preservation of the indigenous folk music of New England,” and overseen the curation of the New England Folk Music Archives, a collection of written, photographic and filmed material that’s housed at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Siggins has received a number of awards and accolades in recent years, among them a Spirit of Folk Award from the International Folk Alliance in 2018. In 2019, at an event hosted by Brian O’Donovan, Club Passim recognized her with a Lifetime Achievement Award, presented by her lifelong friend Baez before an audience that included Patty Griffin, Dar Williams and Peter Wolf. In 2024, she became an inaugural member of the Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame’s (in the non-performer category along with Albert Grossman, former manager of Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin and others, and George Wein, founder of the Newport Jazz Festival and the Newport Folk Festival).

These days, in addition to running Folk New England and the New England Folk Music Archives, Siggins is writing a memoir (with Elizabeth Thompson, author of Joan Baez: The Last Leaf). The working title is as fitting as it is funny: Bad Boys & Daring Girls: Betsy Siggins & The Story of Club 47 & The Music That Changed the World.

(by D.S. Monahan)