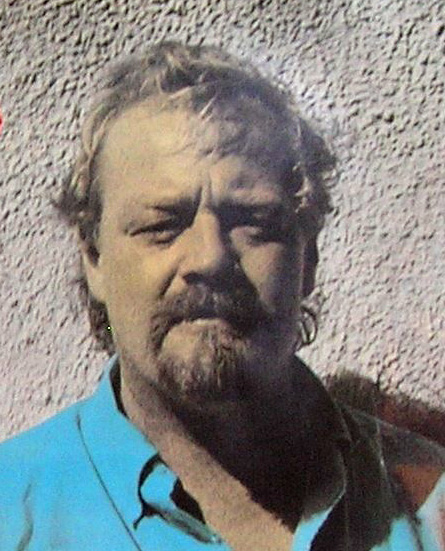

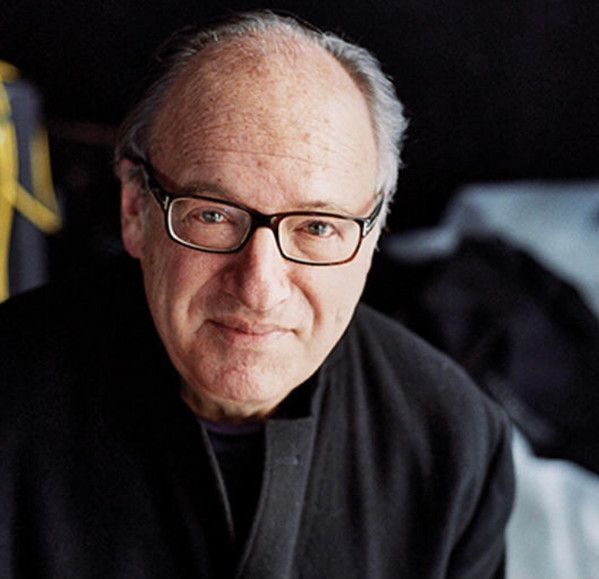

Alex Taylor

There’s no hard proof that musical talent is genetic, but there’s an abundance of circumstantial evidence in the multigenred laundry list of groups that have included at least two siblings. Not convinced? Consider The Ronettes, The Jackson 5, The Shangri-Las, The Beach Boys, The Kinks, The Bee Gees, AC/DC, The Carpenters, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Van Halen, Heart, UB40, INXS, Toto, Devo and Oasis.

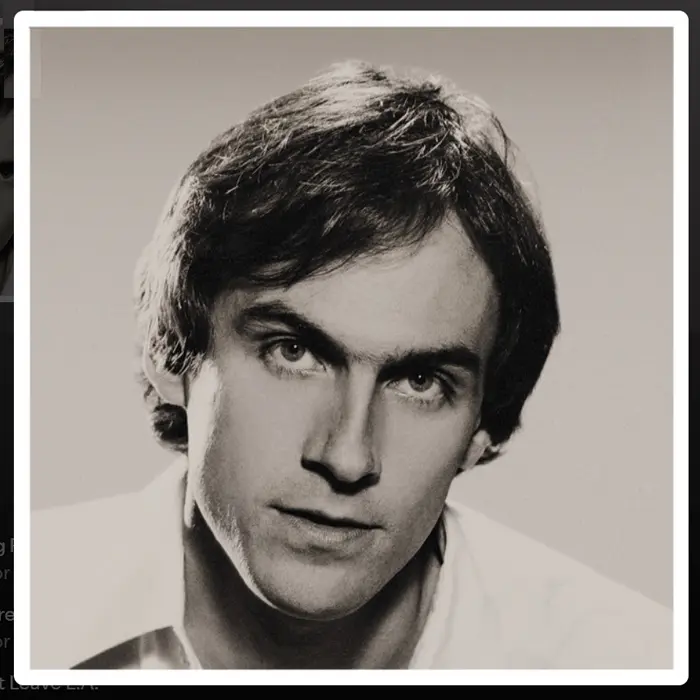

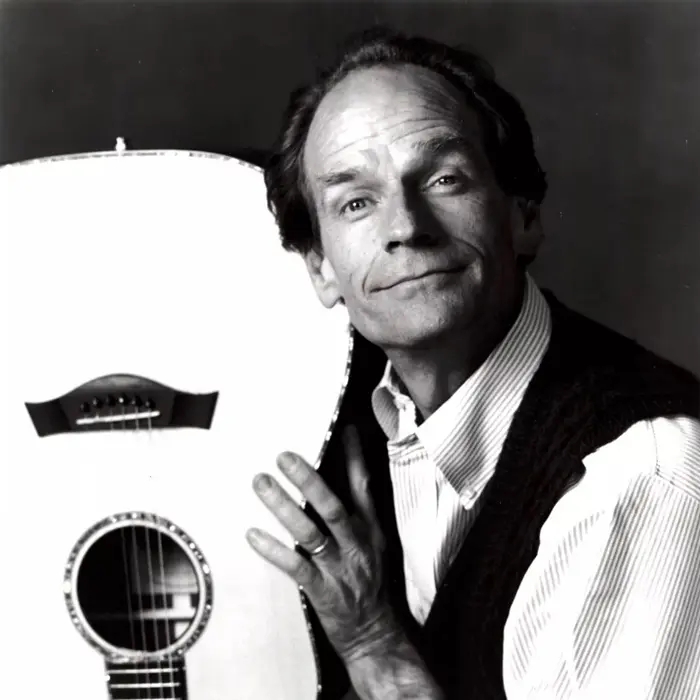

Still not convinced? Consider Alex, James, Kate, Livingston and Hugh Taylor who, though never playing in a formal band together – except when Alex and James gigged as The Fabulous Corsayers briefly in their teens – established successful solo careers and left lasting musical legacies that drive even the most scientific among us to wonder, “Is it really just in the blood?”

OVERVIEW

If one were to draw a line between the five Taylors siblings, it would be a stylistic one: James, Hugh and Livingston’s material tends to be introspective and on the softer side while Alex and Kate’s is more extroverted and acoustically edgy, a mix of Memphis soul, Southern rock, folk, roots and blues that struts more than strolls and seems brash compared to their siblings’ renowned reserve.

And while James included “Steamroller Blues” on his album Sweet Baby James – a song he’s said he wrote as parody of the era’s countless imitation “blues bands” – Alex made the blues his bailiwick and he could belt them out as beautifully as his brothers could bend a ballad. Alex recorded five studio albums, which is four more than Hugh, two less than Kate and a far cry from Livingston’s 15 and James’ 20.

EARLY YEARS, INFLUENCES

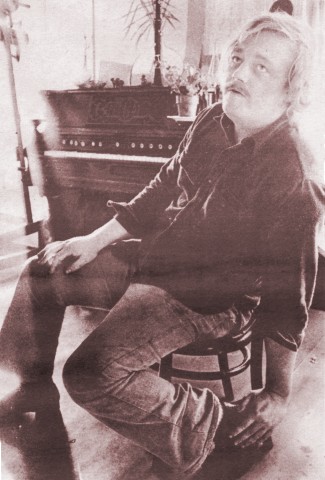

Alexander Robert Taylor was born in Boston on February 28, 1947, the oldest of the Taylor children. In 1951, when his physician father became dean at the North Carolina University of Medicine, his family moved from Belmont, Massachusetts, to Chapel Hill but he remained close to his Massachusetts roots since from 1953 the Taylors spent summers on Martha’s Vineyard, which Alex made his home for most of his adult life.

His mother had studied at New England Conservatory and all her children were exposed to a wide range of music from a young age. By his early teens, Alex was leading frequent family singalongs, playing guitar as they practiced hymns, carols, radio jingles and folk songs, mostly those of Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly and The Weavers.

In early 1964, when James returned to Chapel Hill from prep school in Massachusetts for a semester, he and Alex formed The Fabulous Corsayers with three friends and recorded a single with James’ “Cha Cha Blues” as the B-side.

CAPRICORN SIGNING, THE ALLMAN BROTHERS, WITH FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS

In the fall of 1970, after playing up and down the eastern seaboard for several years, Alex caught the attention of Phil Walden, co-owner of Georgia-based Capricorn Records, which had released Livingston’s debut album earlier that year (produced by Jon Landau) and had recently signed The Allman Brothers Band. The 23-year old Taylor became a regular opening act for the Allmans and later that year recorded his first LP at Capricorn Studios in Macon.

In 1971, which critic Joe Viglione labeled “the year of Taylor Mania,” Capricorn released Taylor’s debut album, With Friends and Neighbors, while Cotilion issued Kate’s debut (Sister Kate), Capricorn released Livingston’s second LP (Liv) and Warner Bros. issued James’ third (Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon). A nine-song collection that tucked neatly into the burgeoning Southern rock subgenre, With Friends and Neighbors featured Capricorn’s renowned house musicians along with James playing guitar on every track. Saxophonist King Curtis, heard by millions as the soloist on Aretha Franklin’s iconic rendition of Otis Redding’s “Respect,” made a guest appearance.

There are no originals on the debut, which includes two songs written by James, “Highway Song” and “Night Owl.” Taylor’s take on Bobby and Shirley Womack’s “It’s All Over Now” – famously rocked up by both The Rolling Stones and The Faces – received especially positive reviews and Viglione wrote that the album was “consistent and highly enjoyable,” calling it “the bookend album to Liv that Sister Kate is to Carole King’s Tapestry [released in January 1971].”

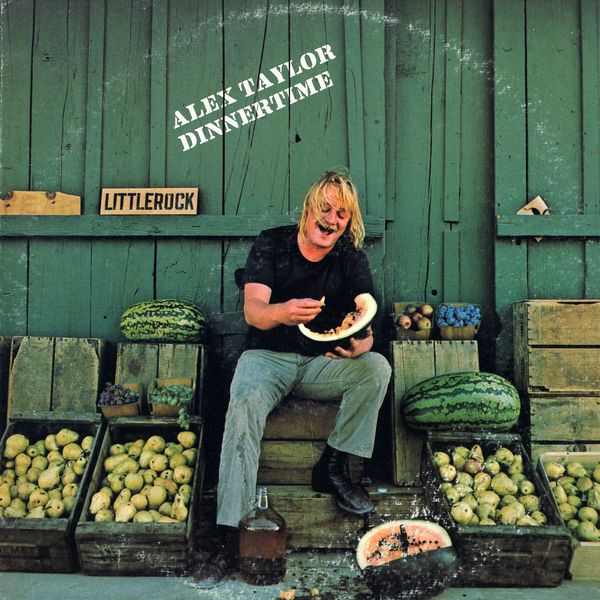

DINNERTIME

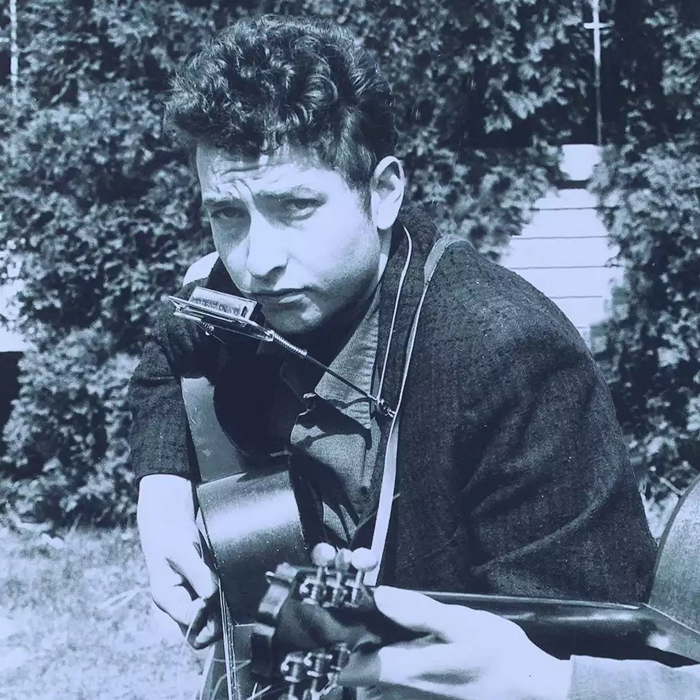

In late 1971, Taylor recorded his sophomore effort, Dinnertime, at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama, using some of the musicians on his debut (not including James) along with Chuck Leavell (piano, keyboards, vibraphone) and Jaimoe (percussion, conga, timbales) from The Allman Brothers Band. Released in February 1972 by Capricorn, seven of the LP’s eight songs are covers of well-known songwriters’ material, including Randy Newman’s “Lets Burn Down the Cornfield,” Stephen Stills’ “Four Days Gone” and Bob Dylan’s “From a Buick Six.” The sole original is “Change Your Sexy Ways,” which Taylor co-wrote with Leavell and guitarist Jimmy Nalls.

Reviews were significantly stronger than they were for Taylor’s first album, with critic Diane Sullivan praising his ferociously full-bore treatment of Howlin’ Wolf’s classic “Who’s Been Talkin’” – “Alex Taylor’s blues throat couldn’t be more unlike his singing siblings,” she wrote – and, in a direct reference to his three brothers, added that he was “as far away from a sensitive singer/songwriter as could be.”

ABC-DUNHILL SIGNING, THIRD FOR MUSIC

In 1974, Taylor recorded his next album, Third For Music, this time for ABC-Dunhill Records. In a 180-degree shift from his previous two LPs, eight of the nine songs were originals, the exception being the James-penned “Rock ‘N’ Roll Music is Now.” Co-produced by James and Allen Toussaint, tracks were recorded in New Orleans and Los Angeles with Alex’s road band, plus the Allman’s Leavell on keyboards and members of the Neville Brothers (then billed as The Meters) on back-up vocals.

For reasons that remain unclear, ABC-Dunhill limited promotion of and touring to support the LP – called “Alex’s lost vinyl” by fans – and by the end of 1974 had dropped Taylor from its roster, a major blow to his future prospects, as his brother Hugh explained in 2017 in comments posted on the website Discogs. “In my opinion, this album was a sort of the death knell for Alex’s career,” he wrote. “ABC [released] the album and cut their losses and Alex was unable to get signed under any [major] label even after.”

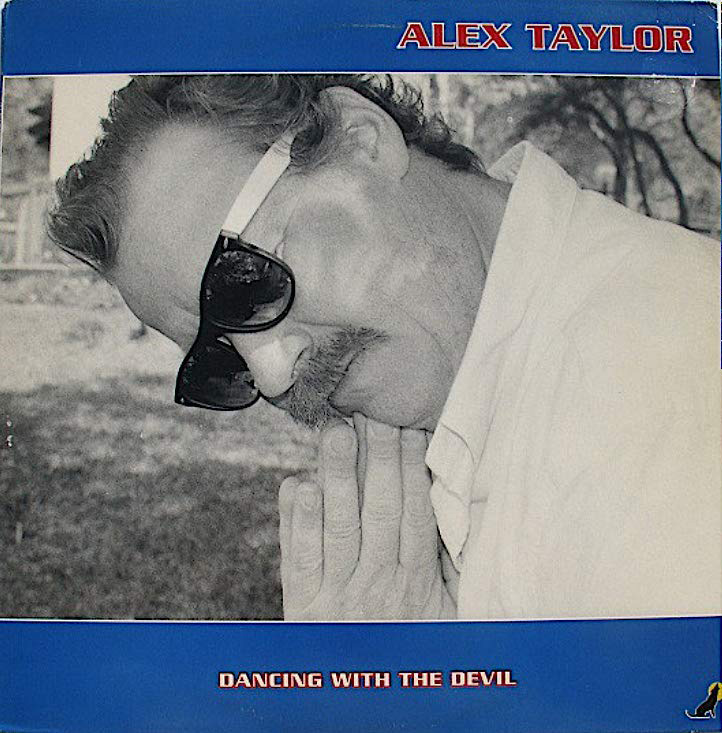

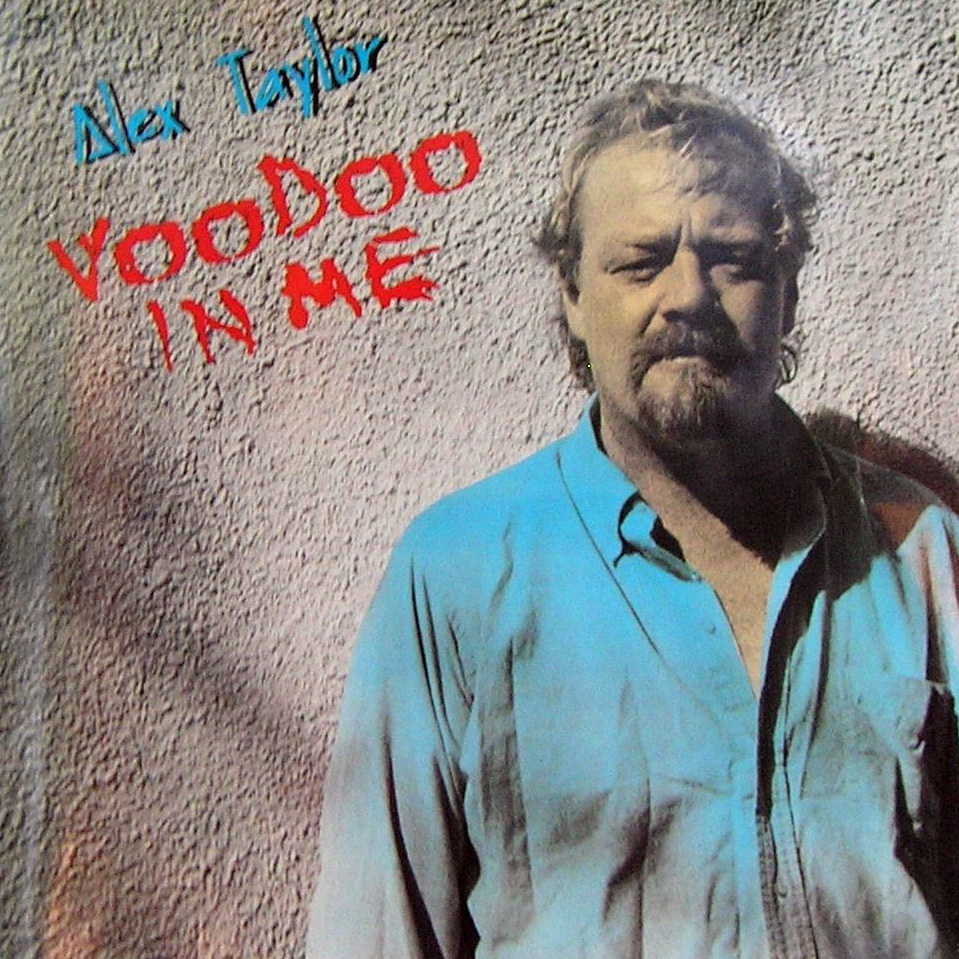

DANCING WITH THE DEVIL, LIVE AT THE HORSESHOE TAVERN, VOODOO IN ME

In 1981, Ichiban Records released Taylor’s fourth album, Dancing with the Devil, a ten-song collection of originals recorded at King Snake Studios in Sanford, Florida, and in 1984 he recorded Live at the Horseshoe Tavern at the famed Toronto club with Dan Aykroyd and the East Coast Funkbusters and Paul Shaffer and the Blues Brothers

Band. In 1989, King Snake Records issued his final LP, Voodoo In Me, which included two originals and James making a guest appearance on one song, Curtis Mayfield and Jerry Butler’s “He Will Break Your Heart.” The closing track, “North Carolina,” is a funked-up, riff-rippin’ blues that several critics hailed as the album’s finest.

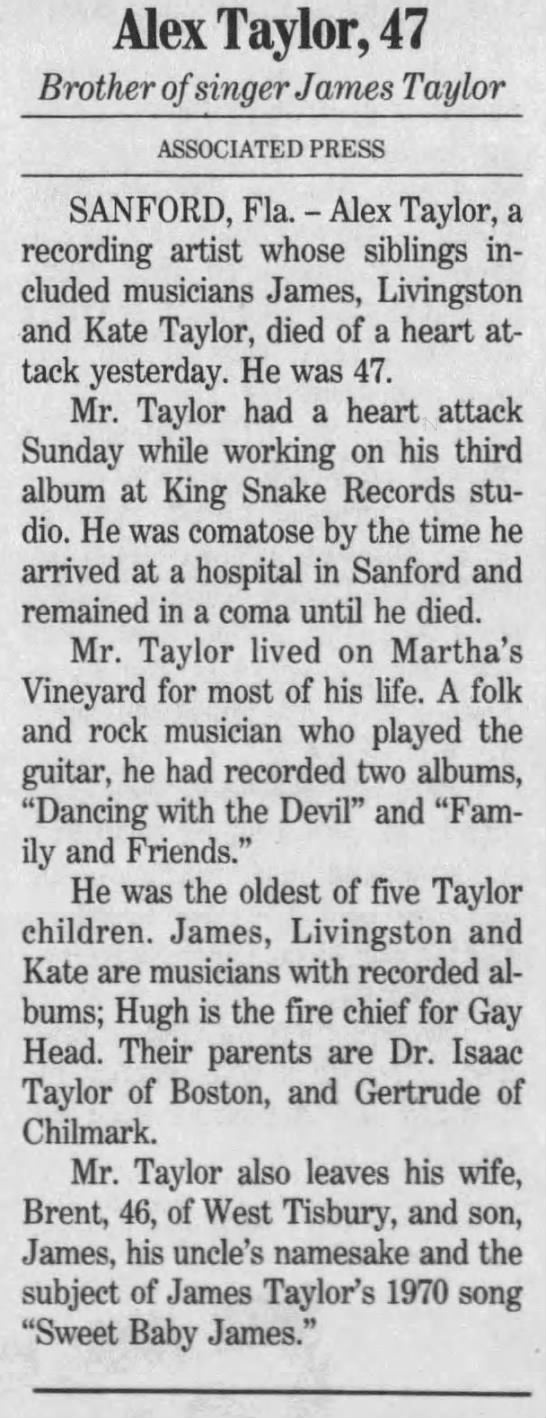

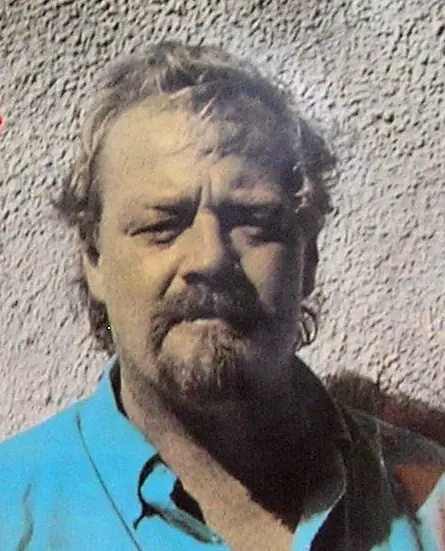

DEATH, LIVINGSTON’S REFLECTIONS

On March 12, 1993 – James’ 45th birthday and just 12 days after his own 46th –Taylor died after suffering a heart attack at King Snake Studios five days before. According to Livingston in a 2008 interview with Living Music Legends (LML), his breathing stopped after he fell asleep in the studio after drinking almost a fifth of vodka – “what was for him, a fully active alcoholic, not an exceptional amount of booze,” he said – and his death was contributed to factors related to alcoholism. Shortly after his death, James wrote “Enough To Be On Your Way” (included on his 1997 LP Hourglass), changing “Alex” to “Alice” in the lyrics.

Speaking in the LML interview about his late older brother, Livingston called him a “great song interpreter, great singer, and as great as an older brother as anybody has ever had” while noting how protective he was when they were growing up. “I went through my entire childhood with the umbrella of my older brother Alex, and it was known throughout Chapel Hill that to commit a trespass against me invited a whooping from him that would not soon be forgotten,” he said. “Nobody touched me.”

“Of course, I had to endure the occasional beating from Alex,” he smiled. “But that was a small price to pay for all that protection. [He was] an amazing guy, generous at the very fiber of his soul.”

(by D.S. Monahan)