A visitor to the Berklee Performance Center in the ‘60s and ‘70s may have been forgiven for a gnawing sense of déjà vu: The headliners changed on a regular basis, but the drummer often stayed the same.

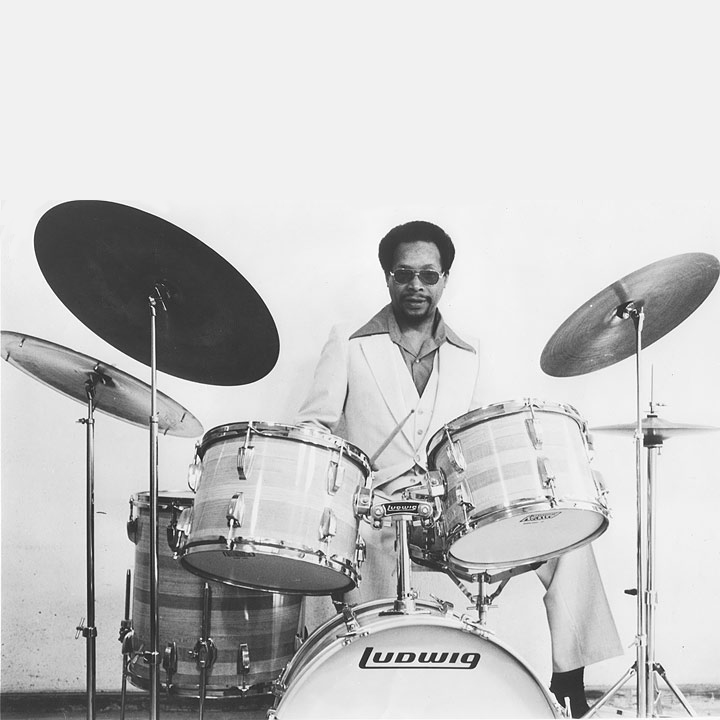

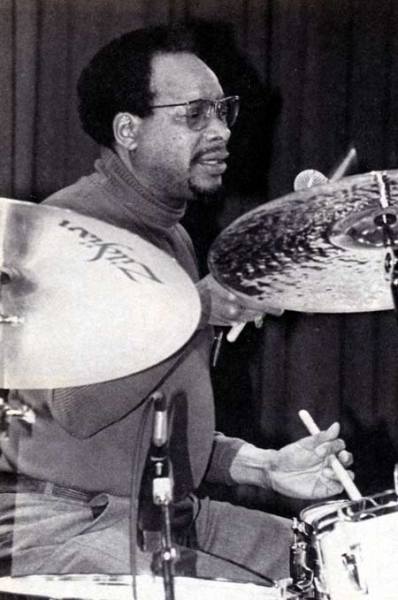

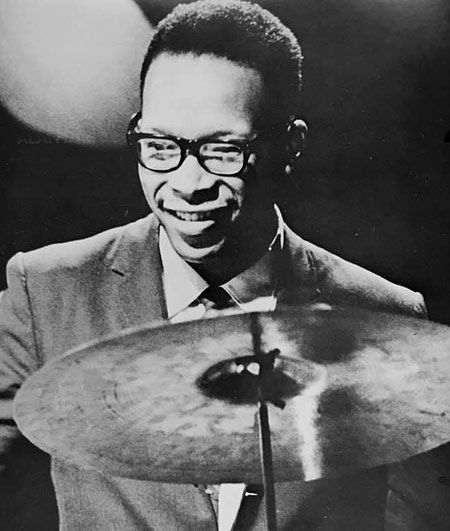

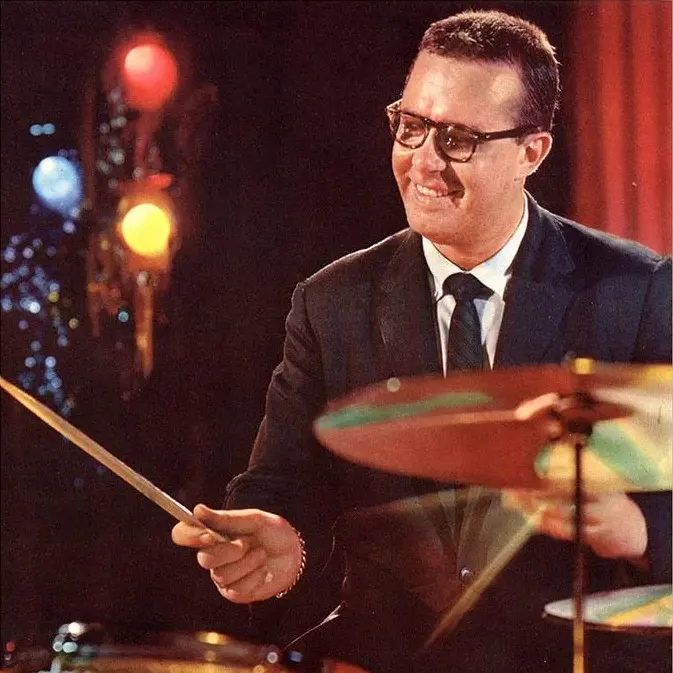

The recurring man of mystery wasn’t part of the fixtures, except in an academic sense. Alan Dawson was both a member of the Berklee faculty, and a professional drummer who played with nearly everyone who was anyone passing through Boston during his active years as a professional musician.

Sabby Lewis, Lionel Hampton, Other collaborations

Dawson was born in Marietta, Pennsylvania in 1929 but grew up in Roxbury. He began to study drums (and vibes) at the Charles Alden Drum Studio in Boston in 1947. He freelanced around town before catching on with Sebastian “Sabby” Lewis, a pianist who led the best-known and longest-lived Black band in town. Dawson served in the Army during the Korean War, playing with the Army Dance Band at Fort Dix, New Jersey, from 1951 to 1952, and when he was discharged joined vibist Lionel Hampton’s band, with whom he toured Europe.

Dawson would re-join Sabby Lewis in the mid-1950s, then later play with such Boston regulars as trumpeter Frankie Newton, baritone sax Serge Chaloff, and pianist Jaki Byard. He went on to play with nationally-known figures such as tenor Booker Ervin, and in 1968 he replaced Joe Morello in The Dave Brubeck Quartet. Dawson can be heard on records by tenors Al Cohn and Dexter Gordon, altos Lee Konitz and Sonny Criss, and guitarist Tal Farlow; his 1972 recording date with Boston native Sonny Stitt, “Tune Up,” is considered one of the tenor’s best albums.

Berklee professorship, Drum method, Teaching style

Dawson began to teach drums without having planned to; he was approached by the father of a young drummer named Clifford Jarvis, who asked him if he’d be willing to tutor his son. Dawson agreed, and thus began a career that provided him with a steady income and a home base, a welcome change from the rigors of the road and inconstant work that are the occupational hazards of life as a jazz musician.

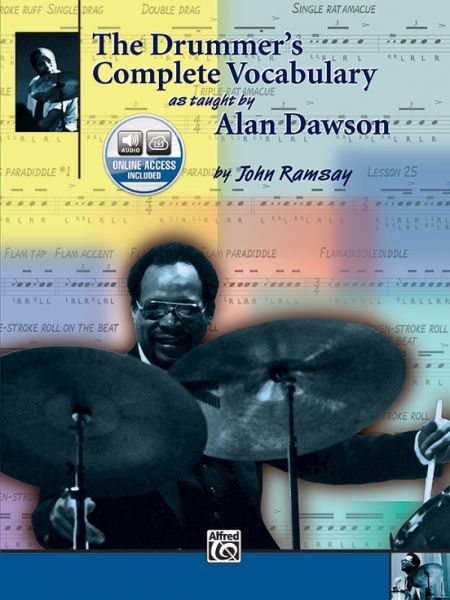

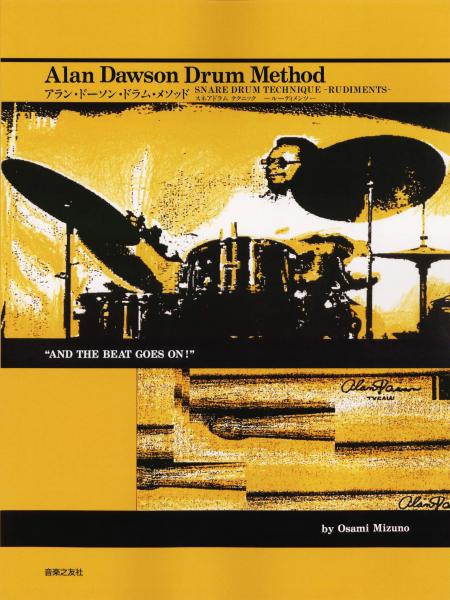

In 1957, he joined the faculty at Berklee, and over the course of his career there he taught Tony Williams and Terri Lyne Carrington, among many others. In 1975, Dawson suffered a ruptured disc that brought an end to his touring and his full-time job at Berklee, and thereafter he taught out of his home in Lexington, Massachusetts. Dawson developed his own drum method, and in the ‘60s published a book about it – The Drummer’s Complete Vocabulary As Taught by Alan Dawson – which is still in print. His teaching style emphasized the music as a whole, and not just drumming as a component part.

Recalling Ben Webster’s belief that an instrumentalist needed to know the lyrics to a song in order to create a meaningful solo, Dawson told students to learn the structure of a tune in order to be better percussion accompanists; he directed students to play over standards while singing the melody out loud so they would learn not to elevate technique over expression. He wrote exercises to be played with brushes on the theory that a drummer who practiced with them would learn to pick up the sticks rather than relying on drumstick “rebound.”

Club Mt. Auburn 47 appearances, Death

In an act of outreach that may strike jazz purists as missionary work among the infidels, in 1959 Dawson formed a group with bassist John Neves and his pianist brother Paul that played not in smoky bars over the noise of clinking beer glasses, but in a Cambridge coffeehouse, Club Mt. Auburn 47 (which became Club 47 in 1963 and Club Passim in 1969).

Dawson died in 1996, five months short of his 67th birthday.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges, (2019, Oxford University Press), winner of Hot Club de France’s Book of the Year Award, and Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (2023, Equinox Publishing).