Ace Recording Studios

The simple-as-could-be radio jingle for Ace Recording Studios said it all: “Ace is the place…to make recordings.” And for more than three decades, it wasn’t false advertising.

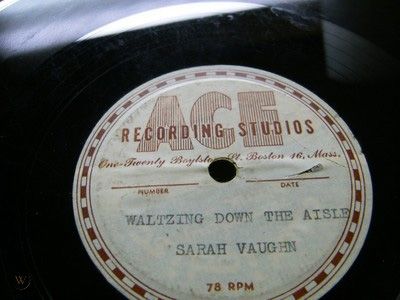

Opened on April 15, 1946 – when Perry Como’s “Prisoner of Love” was #1 in the US and over a decade before Elvis debuted on The Ed Sullivan Show with “Hound Dog” – Boston-based Ace was the first full-service commercial recording studio in New England and its closest competitors, the RCA, Decca and Columbia studios in New York City, were some 200 miles away. Ace differentiated itself with its enormous live studio – roughly three times larger than recording rooms even some of the major label’s studios offered – which could easily hold a 40-piece orchestra and housed a custom-designed, natural-sounding echo chamber, a “room within a room.” The gigantic space could be isolated into sections to allow smaller combos to achieve superb sound; the combination of that and the amazing acoustical ambiance the room provided larger ensembles made Ace “the place” for an eclectic range of singers and musicians from the mid-‘40s through the late ‘70s.

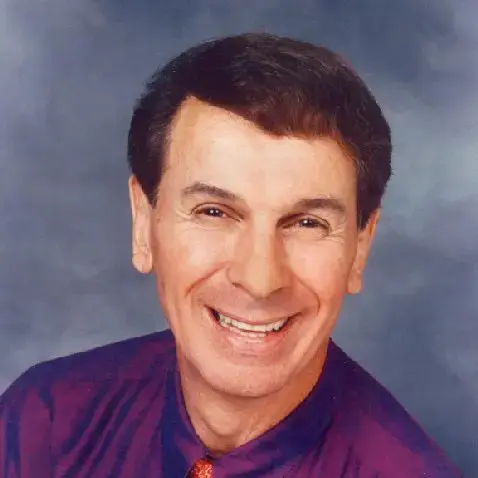

Owners: Milton and Herb Yakus

The studio was founded by the Boston-born Yakus brothers, 28-year old Milton (b. December 25, 1917) and 19-year old Herb (b. December 20, 1926), both Army veterans, the latter of whom was wounded in the pivotal Battle of Remagen in March 1945. Each had a deep love for music – Milton a huge fan of the big-band style and Herb an amateur saxophonist – and prior to founding Ace, Milton was an independent producer who booked on-air musical acts, wrote dialogue, produced and recorded shows in collaboration with Boston radio station WMEX and various New York studios.

Milton’s exposure to the ins and outs of recording through making those shows and his end-to-end knowledge of the music business made ownership of a studio a logical career move. He leapt at the opportunity to set up shop at Ace’s 1 Boylston Place location when the building became available because its central setting and sheer size made it the perfect place for him and Herb to execute their pioneering plans.

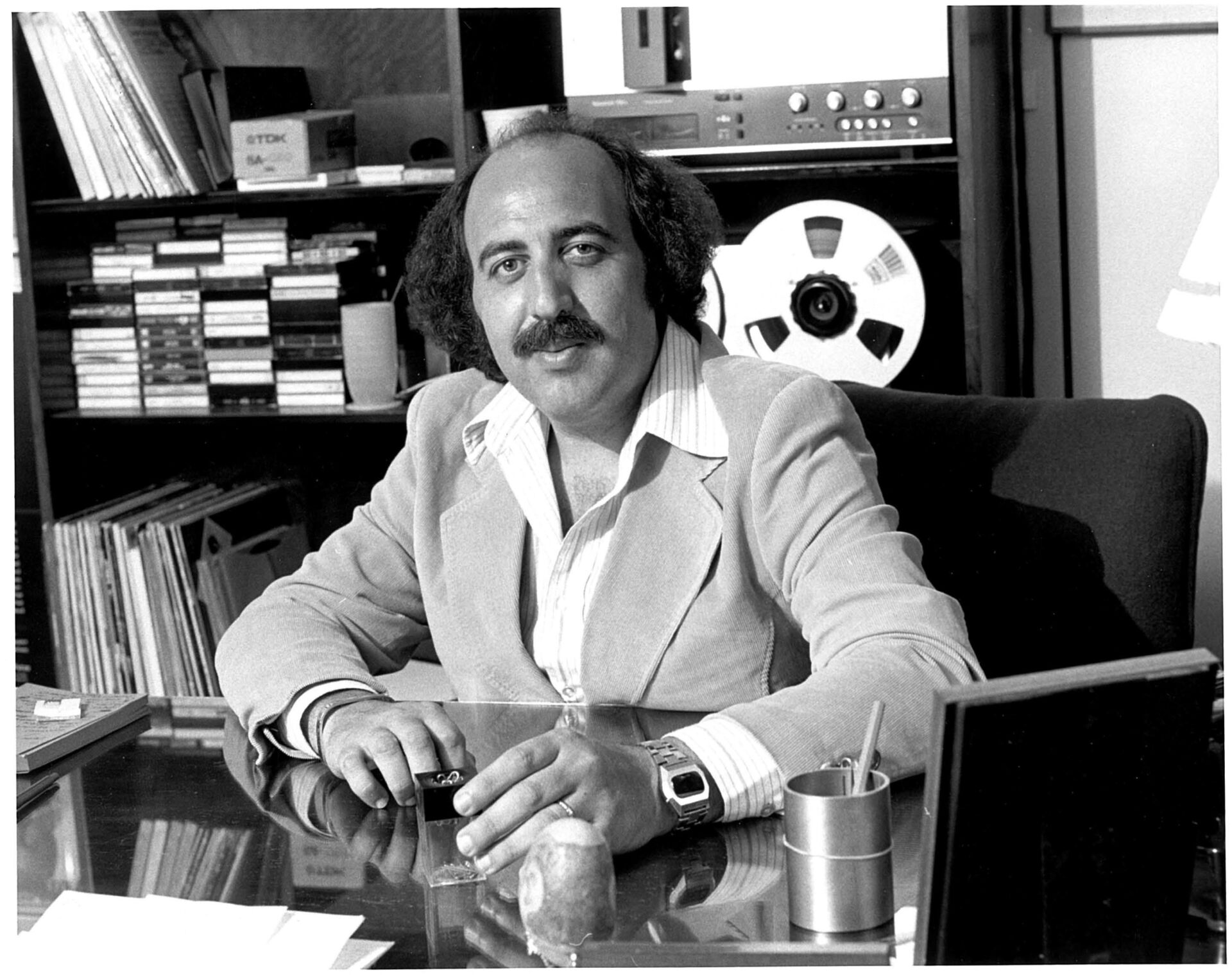

Chief Engineer: William F. “Bill” Ferruzzi

Ace’s chief engineer was Bostonian William F. “Bill” Ferruzzi (b. March 29, 1920), who trained in audio engineering while serving in the Navy and worked for several Boston-area radio stations before teaming up with the Yakus brothers He was in charge of all the studio’s technical aspects – from setting up the microphones and tape machines to tape editing and copying – and showed Herb the engineering ropes, the two often working together in the control room, which Ferruzzi designed. He also designed the echo chamber, a concrete-block acoustical marvel with a speaker at one end and microphones at the other that singers and musicians praised as unlike anything they’d seen or heard in other studios.

While Ferruzzi and Herb handled the hands-on recording aspects of the business, Milton managed the administrative, legal and promotional ends including booking the studio, hiring singers and musicians, generating musician’s union contracts and selling Ace’s unique features/benefits to potential clients at every opportunity.

Perfect timing, 33⅓-rpm LPs, 45-rpm singles

The studio’s mid-‘40s opening was perfectly timed, coming shortly before the introduction of 33⅓-rpm albums and 45-rpm singles and major advances in recording technologies. In 1948, Columbia Records released the first widely circulated 33⅓-rpm LP, which allowed for 22 minutes/side – over four times that of 78s – and in 1949 Columbia’s arch rival RCA Victor released the world’s first 45-rpm single. The Yakus brothers knew that both developments – among the most pivotal in music-business history – were golden opportunities.

As for recording, two-track machines had been around since 1933 but by 1948 three-track systems were available, then four-tracks by the mid-‘50s, eight-tracks by the late ‘50s and 16-track systems by the mid-‘60s. Although Ace updated from mono to two-track in the ‘50s and then two-track to four-track in the ‘60s, the studio never offered to eight- or 16-track.

Charting artists, Songs

While Ace’s main business was recording singers, musicians and voiceover actors for radio and television commercials, both local and national, the studio produced a number of pop/rock hits from the mid-‘50s to early ‘60s. The first came in 1955, when the Roxbury-based vocal quintet The G-Clefs recorded their infectious single “Ka-Ding Dong” with 16-year old Frederico Anthony Picariello – later known as Freddy Cannon – on guitar and it reached #24 in Billboard Hot 100. The track put Boston on the map as a music-making mecca decades before The J. Geils Band, Aerosmith and Boston cemented the city’s rockin’ reputation.

The G-Clefs recorded several other tracks at Ace including “I Understand (Just How You Feel),” which hit #9 in 1961, and two other top-10 hits resulted from sessions at the studio: The Tune Weavers’ “Happy Happy Birthday Baby” (1957, #5) and Cannon’s “Tallahassee Lassie” (1959, #6), his signature song. Boston-based garage bands The Rhythm Rockers and The Rondels – both with future VP of Epic/Portrait Records Lennie Petze on guitar – cut multiple tracks at Ace including the latter’s “Back Beat #1,” which went to #66 in 1961.

Other artists recorded, Van Morrison audition

Among the other artists/groups that recorded at Ace were jazz acts The Ray Borden Orchestra, The Billy Taylor Trio and singer Nancy Johnson, jazz/blues quartet Hap Snow’s Whirlwinds, garage bands Teddy & The Pandas, The String-A-Longs, Ricky Coyne and The Guitar Rockers, The Barbarians, Hermon Knights, The Knights and Jan Tanzy, Armenian folk group The Aramite Band, traditional Irish singers The Finian Folk and New Hampshire-based vocal trio The Royal Coachmen.

In 1968, Van Morrison auditioned for producer Lewis Merenstein at Ace, which resulted in Chelsea, Massachusetts, native Joe Smith signing the Irish singer-songwriter to Warner Bros. and Morrison’s first LP for the label, the Merenstein-produced Astral Weeks (recorded at Century Sound in New York, not at Ace).

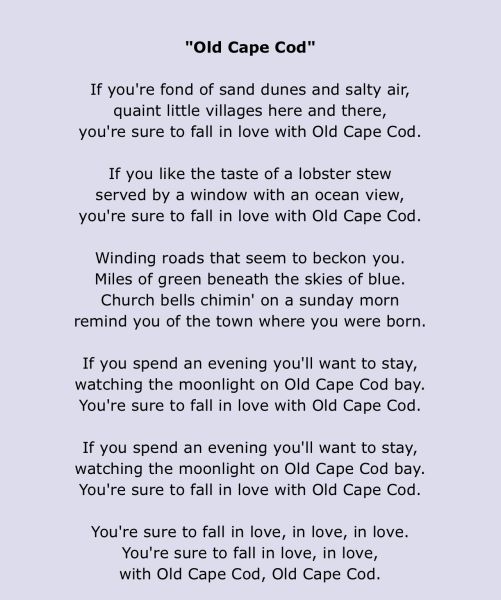

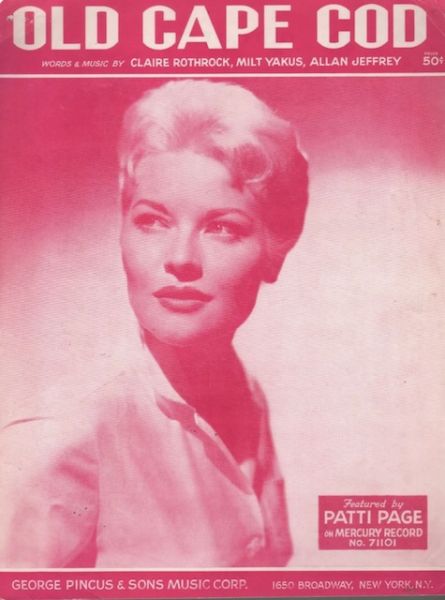

“Go On with the Wedding,” “Old Cape Cod”

Separate from the recording side of his business but at least as important to his legacy, Milton was also a songsmith who in 1956 co-wrote Patti Page’s #11 hit “Go On with the Wedding,” the Kitty Kallen and Georgie Shaw rendition of which went to #39 later that year. His most famous tune, “Old Cape Cod” – a chart-topping pot of gold rhyming “lobster stew” and “ocean view” – came a year later after Boston-area native Claire Rothrock showed Milton a poem she’d written about the Cape and Milton, sensing a potential smash, wrote a bridge, put the lyrics to music and recorded a demo at Ace with local singer Pat O’Day.

On April 23, 1957, Mercury Records released Patti Page’s rendition (recorded in New York), which soared to #3 in Billboard‘s Top Played by Jockeys chart, #7 in the Billboard Top 100 and is now considered a pop-vocal classic – and Cape Cod’s unofficial anthem. The Cape Cod Chamber of Commerce gave Milton an award for helping to make the area a booming tourist destination and in 2010 renamed the road leading to the Chamber “Patti Page Way.” For 23 years, from 1957 until the studio closed, the “Old Cape Cod” sheet music was displayed in a glass case at Ace’s main entrance.

Royalties, George Pincus, “Allan Jeffrey”

But the song’s success story is not that simple. Upon hearing the demo, New York-based music-publishing giant George Pincus came to Boston to negotiate for the publishing rights, using a strong-arm tactic that was quite common in that era: He said one of his contacts (unnamed at the time) could get a major artist (meaning Patti Page) to record “Old Cape Cod” if Milton and Claire shared the writers’ credits with said contact.

Reluctantly, the two actual songwriters agreed, learning years later that the contact credited on the song, Allan Jeffrey, was in fact an alias for Irwin Pincus, George’s son. He wound up being paid 1/3 of the writing royalties – despite not having written one single word or note of the song – while his father reaped 100% of the publishing profits.

Closing, Deaths, Milton’s musical sons

On July 7, 1980, 34 years after its establishment, Ace Recording Studios closed after the City of Boston decided to take its 1 Boylston Place location by eminent domain as part of an urban-renewal program. As the building owners, Milton and Herb faced massive reductions in potential rental income and determined that the best available option was to shut the studio’s doors for good.

Four months later, on November 6, 1980, Milton died at age 62. By then, his son Shelly (b. 1945) was an engineer and vice president at The Record Plant in New York collaborating with John Lennon, Chick Corea, Lou Reed and many others. In 1985, he and Jimmy Iovine oversaw the rebuilding of every A&M Records studio and Shelly later became vice president of A&M Studios in Los Angeles. Milton’s other sons, Bernie and Joey, founded Quincy-based Shooting Star Promotions, working with a variety of Boston-area talent including A&M recording artists Caribbean Express, who received a Grammy nomination for Best Tropical Latin Performance in 1988.

Ferruzzi worked as chief engineer at Fleetwood Recording Studios in Revere for many years before his death in 2011 at age 91. Herb passed away three days after his 92nd birthday, on December 23, 2018.

Groove Armada, “Old Cape Cod” Sample

Just like its opening in 1946, Ace’s closing in 1980 came on the cusp of a pivotal period in recording history – the advent of sampling – and in 1997 the British electronic-music duo Groove Armada included a sampled loop of Patti Page’s “Old Cape Cod” in their single “At the River.” It went to #9 in the UK, introducing a new generation to an old song first recorded 40 years before at Ace – when it was “the place…to make recordings.”

(by D.S. Monahan and Lennie Petze, in collaboration with Shelly Yakus)