A Tribute to the Real Father of Classic Rock Radio

It wasn’t called “classic rock” all those years ago. It really didn’t have a name. But it was definitely a new kind of music. It was music on fire. Hendrix, Morrison, Clapton. After I heard it for the first time, it took me a week to get my eyes closed.

Here’s some perspective: AM radio was still king in the early/mid-‘60s. Big, 50,000-watt flamethrowers like WBZ in Boston, WABC in New York City, WLS in Chicago and KFI in Los Angeles ruled. Almost all of them were built on tight, top-40 foundations. The play list at WABC was often more like the top 20, with the emphasis on the top three – “All Hits All The Time.” Jingle, jangle, jingle. The format was the book. Except at WBZ since the station never followed a standard “format.” All of us on the air at ‘BZ played whatever we wanted, including records from our personal collections and tapes of local artists. And in between every single, album or tape, we had fun. Oh, we had fun. And people loved it. For example, today’s top radio stations pull around a 10 rating in a major market; WBZ consistently pulled north of a 25.

The mouths at WBZ belonged to Carl DeSuze, Dave Maynard, Jay Dunn, Jeff Kaye, Ron Landry, Bob Kennedy, Bruce Bradley and me. But the brains, and a lot of the heart of the station, belonged to the program director, Al Heacock. Al was smart. He was a quiet guy who made a lot of money in the stock market. But he really didn’t care about the stock market. He cared mostly about his radio station, WBZ, which was a broadcaster with ‘tude. When we aired from our mobile studio (which was most of the time), we proudly wore our station blazers. It wasn’t unusual at all for us to drop in on each other’s shows and kibitz for a while. When you walked down the beach, you didn’t need to bring your own radio because everybody around you would have ‘BZ turned on and turned up to stun. If you stopped your car at a red light, you’d practically always hear ‘BZ playing in the car beside you.

For those of you who never heard of WBZ – and for those of you who work in radio and are curious about the legendary station – here’s how Al programmed his music: Each month there was a staff meeting, during which he’d always remind us to play some of the top tunes he left in the studio rack. Then he’d say, “I don’t want to hear two records back to back. We pay you guys to entertain. Entertain!” What a joy it was, what an honor, to be a WBZ deejay.

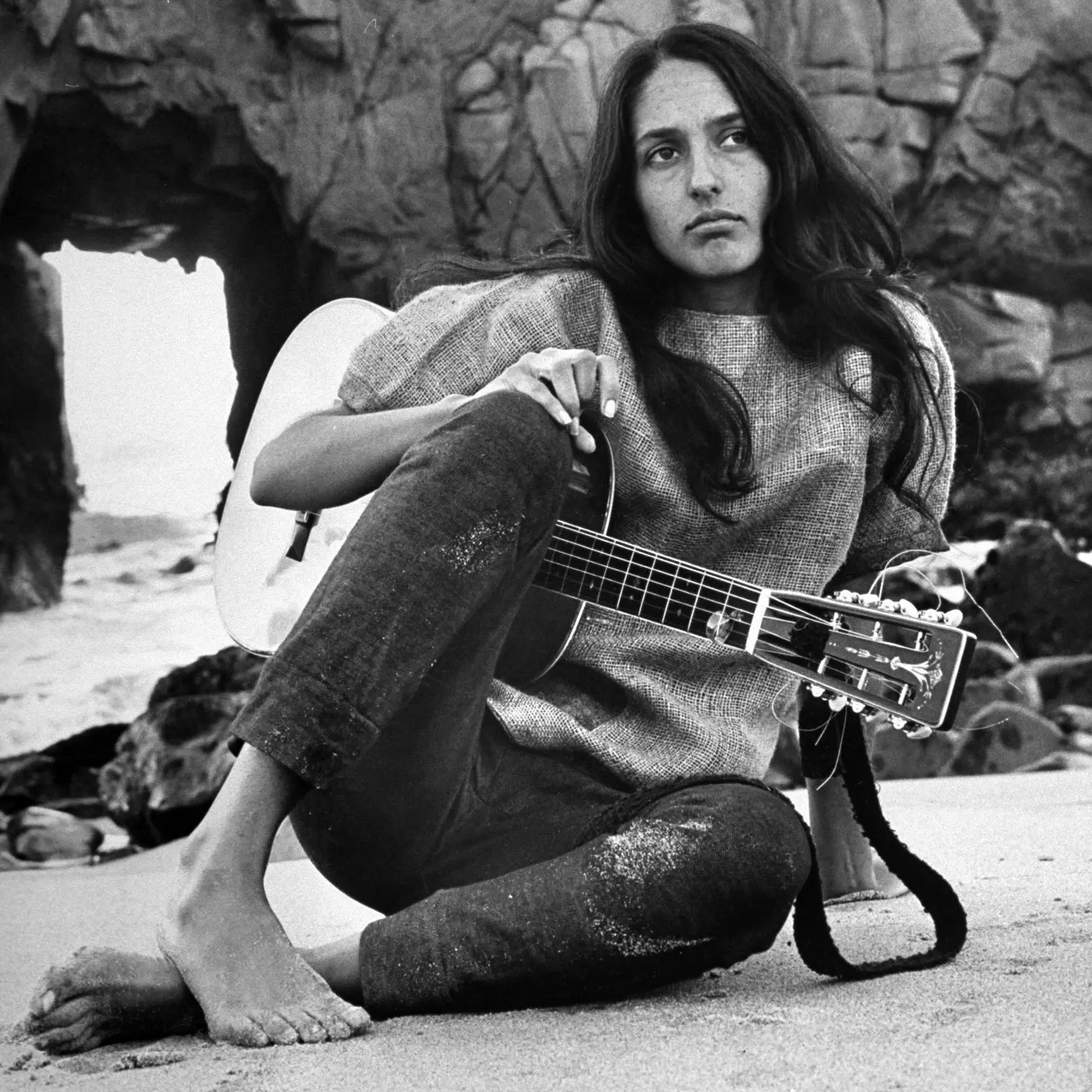

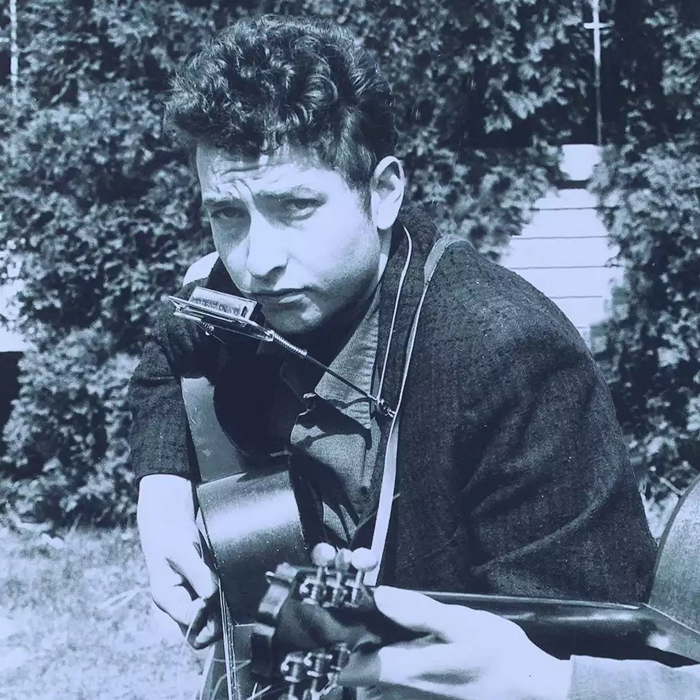

Here’s where the “Father of Classic Rock” stuff comes in. Because it’s a big college town, Boston has always had a strong folk-music tradition. Based on that, at ‘BZ we consistently played original tapes of unreleased songs such as “Sounds of Silence” by Simon and Garfunkel and “The Urge for Going” by Tom Rush along with all kinds of stuff by Dylan, Joan Baez and “Sweet Judy Blue Eyes” Collins. I did an emcee gig weekly at the Unicorn Coffee House, one of the city’s top folk spots, and I noticed that some of the artists were beginning to “go electric.” One night, I invited Al to the Unicorn and he immediately understood what was going on. The very next day, he instigated ‘BZ’s only mandatory music rule: “One ‘liquid rock’ song per hour” (since that’s what he called the new, electrified variety of tunes). Almost immediately, that new sort of sound became known as “underground rock”; the name was the only thing Al got wrong about the electrified trend.

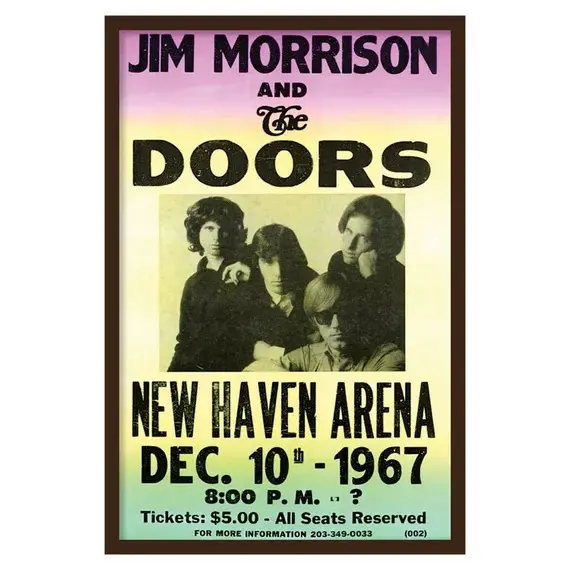

He set aside two hours on Sunday evenings for the first “underground rock” radio show, Subway,” which I hosted. Then Dylan famously “went electric” at the Newport Folk Festival in ’65, Eric Clapton formed Cream in ’66, Woodstock forged a new musical and political conscience for America in ’69 and all of it went roaring out on WBZ’s 50,000 watt clear channel signal from Massachusetts to Midway Island in the Pacific. The suits at Group W Radio, ‘BZ’s parent company, were aghast. It wasn’t top 40. It wasn’t anything that they recognized. They didn’t like it. And they wanted it stopped – right now. Al just said “no,” very quietly. For a while, even the suits didn’t want to mess around too much with a 25 rating in Boston.

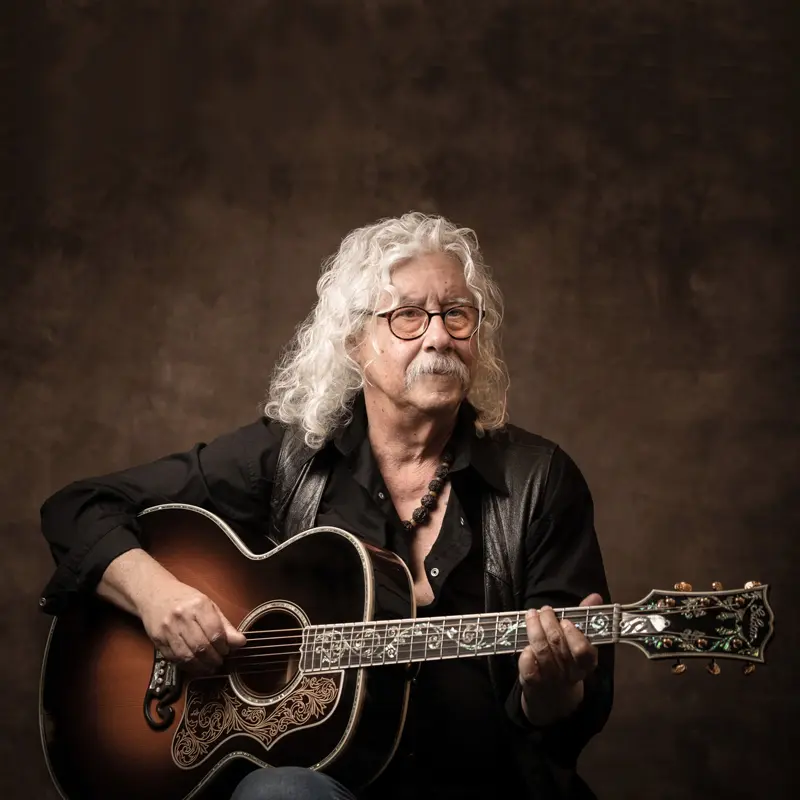

Then, in 1967, Arlo Guthrie recorded his song “Alice’s Restaurant,” which included a line about the “mother rapers and the father rapers on the Group W bench.” The lawyers at Group W headquarters freaked. The president of the company flew from New York City to Boston to talk sense into this crazy program director named Al Heacock. “Get it off the air now” was the order. Once again, Al just said “no,” very quietly. It was a classic Radio Guy vs. Big Suit moment. And Mr. Suit blinked. The order was changed to “Well, at least edit that line out.” And yet again, Al just said “no,” very quietly. So, Mr. Suit decided to drop in on me during the Subway show for what he called “a friendly visit.” The engineer called Al to alert him to the situation and 10 minutes later he was at ‘BZ asking Mr. Suit to join him for a quick meeting outside of the studio. That’s the last I heard about the problem.

Shortly afterwards, Al was transferred to WINS in New York City. A few months later, Group W turned off the music at WINS and started a highly successful all-news format on the station. And just a few weeks after that, Al was found dead in his shower. They called it a coronary. But I think they just broke his heart.

The great Tom Donahue climbed aboard the “underground music” train in 1967 as the program director at KMPX-FM in San Francisco, Boston classical station WBCN-FM went rock in early ’68, WNEW-FM in New York City did the same and pretty soon FM had killed the AM king. It probably would have happened anyway. But the point is that whenever you hear “Stairway To Heaven” or “Light My Fire,” you’re listening to one of the many echoes of the quiet but firm “no” that Al Heacock repeatedly said all those years ago. I may have mixed up some of the specifics – it’s been a long time – but that’s how I remember it.

So, here’s to the real “Father of Classic Rock Radio.” A guy you’ve probably never heard of. A guy who knew how to “just say no.” WBZ’s Al Heacock. Rest in peace, my friend. You taught me more than even you knew. You set me free on the air. Free, the way the air should be. You were a lesson in how to be a real gentleman –a real and gentle man. And for a whole generation of people who love music, you set the world on fire.

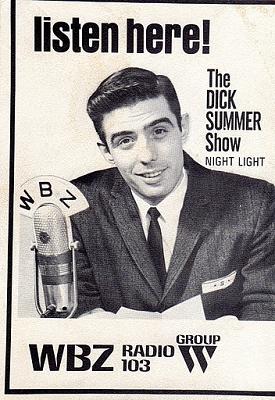

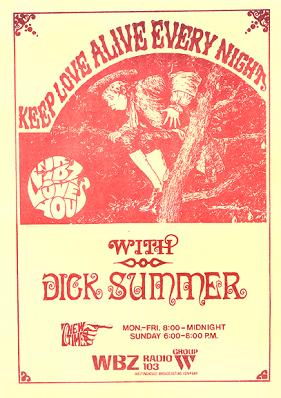

(by Dick Summer)

Dick Summer was a deejay at WBZ from 1963 to 1968 and again from mid-1971 to early 1972. From early 1969 until mid-1971, he worked as program director/deejay at Boston’s WMEX. He died on May 14, 2024 at age 89.