A Night With Jaime Brockett

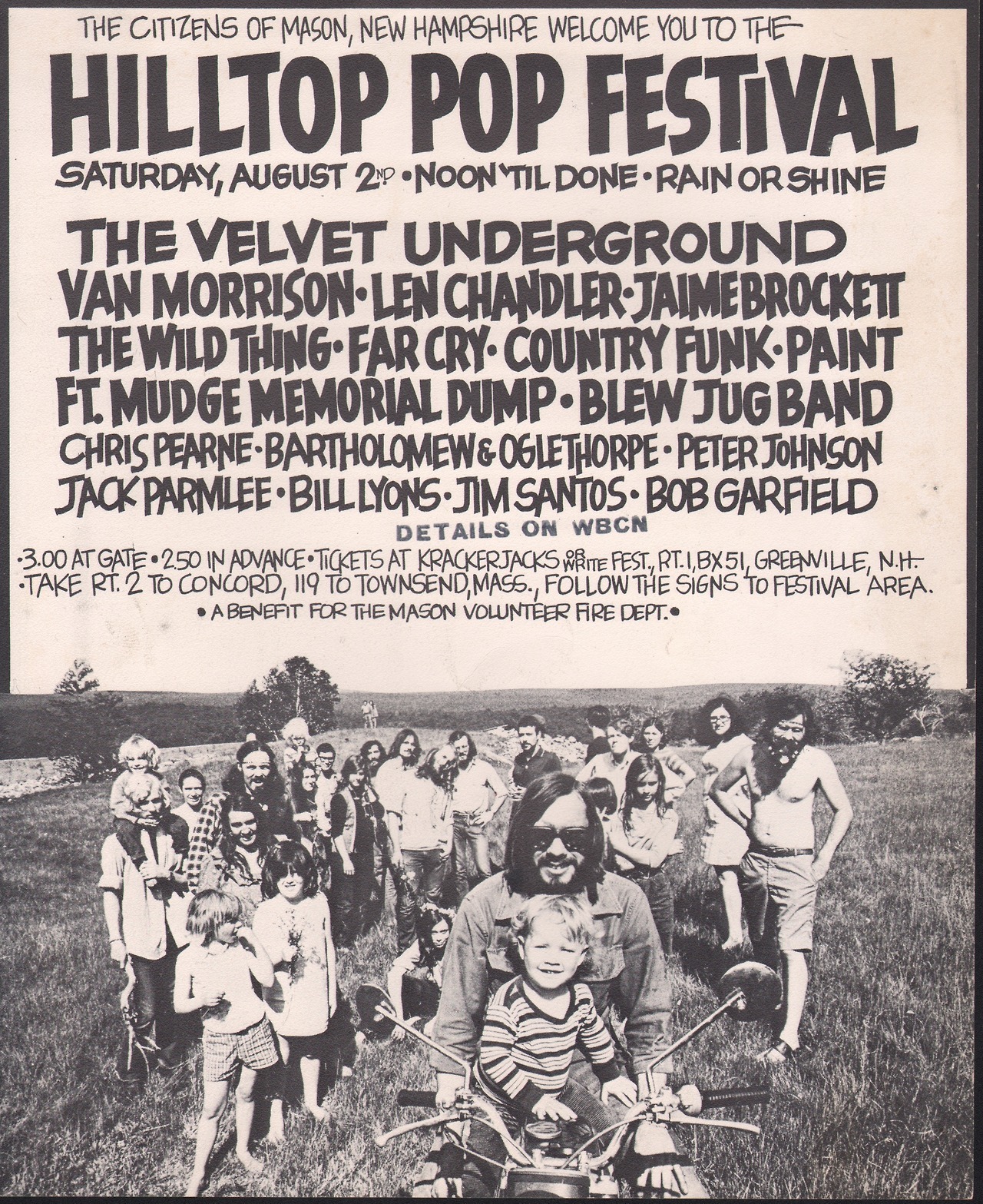

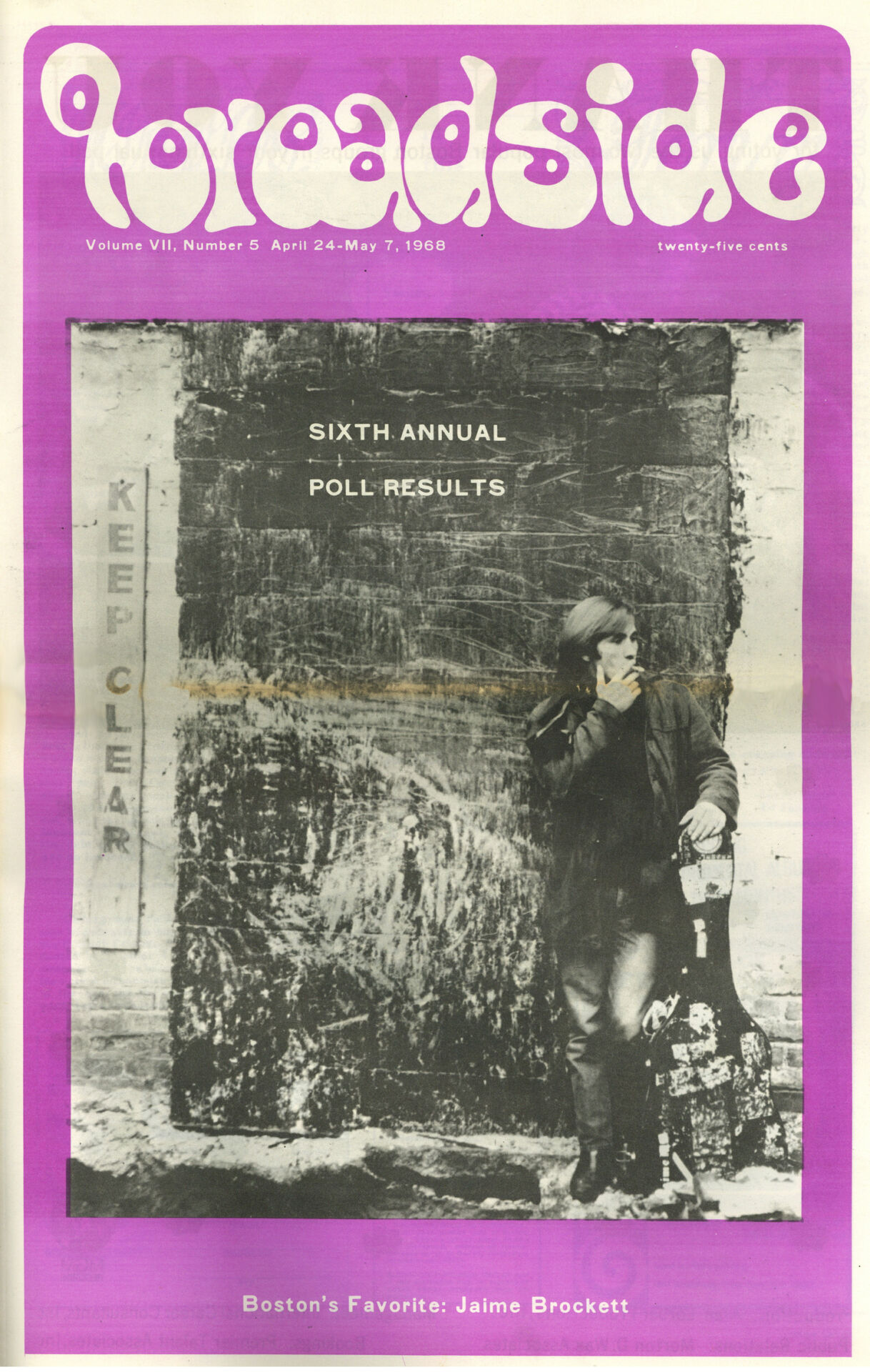

I first met Jaime Brockett at the Y-Not Coffeehouse on Main Street in Worcester during the mid-sixties. He walked on stage with a hotel-toilet-seat “Sanitized for your protection” strip wrapped snugly around the body of his guitar. He had recently returned from Denver, where he’d met Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, who’d become his mentor and a major influence. Throughout ’67 and ’68 he would stop by Congress Alley whenever he was passing through Worcester, often staying for an all-night session of pickin’ and grinnin’.

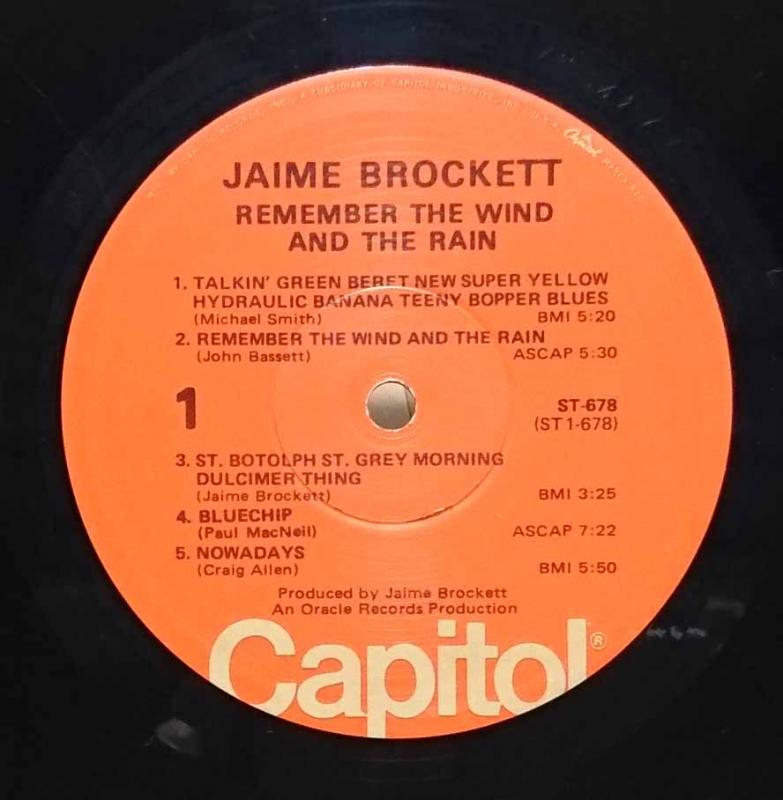

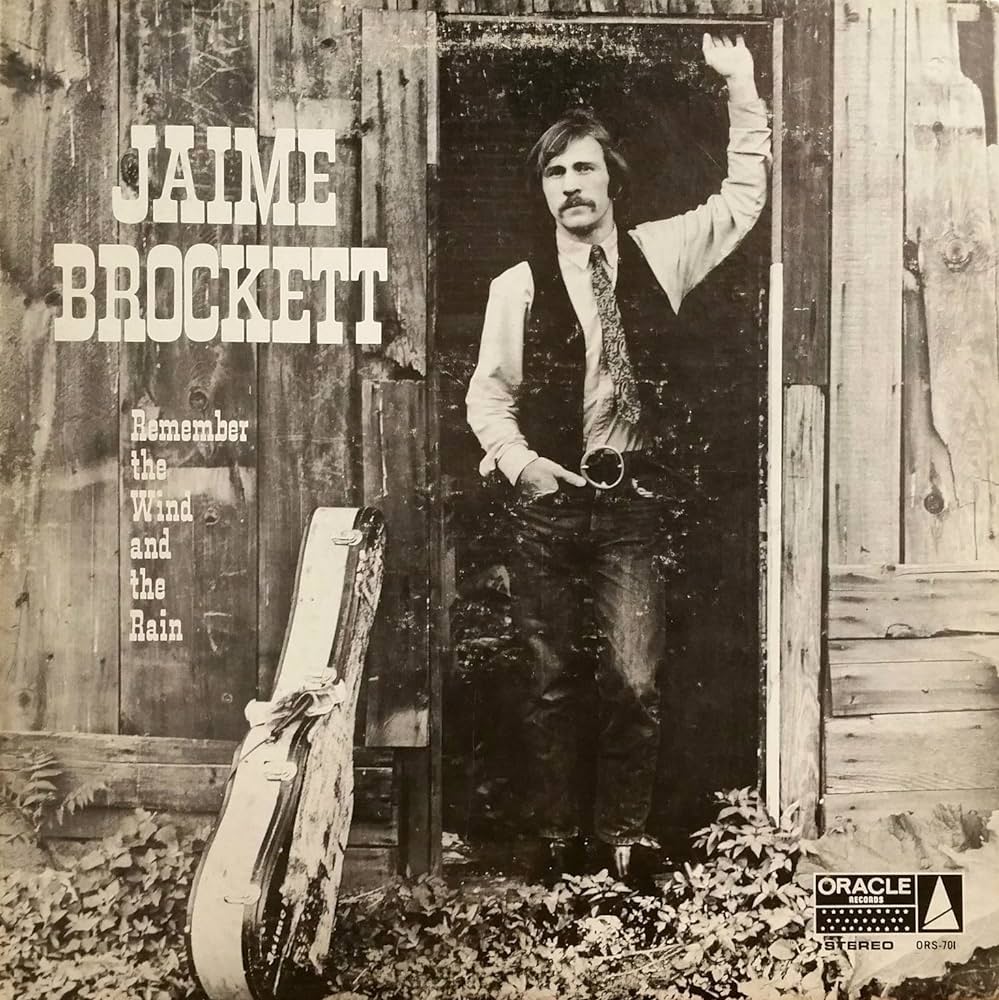

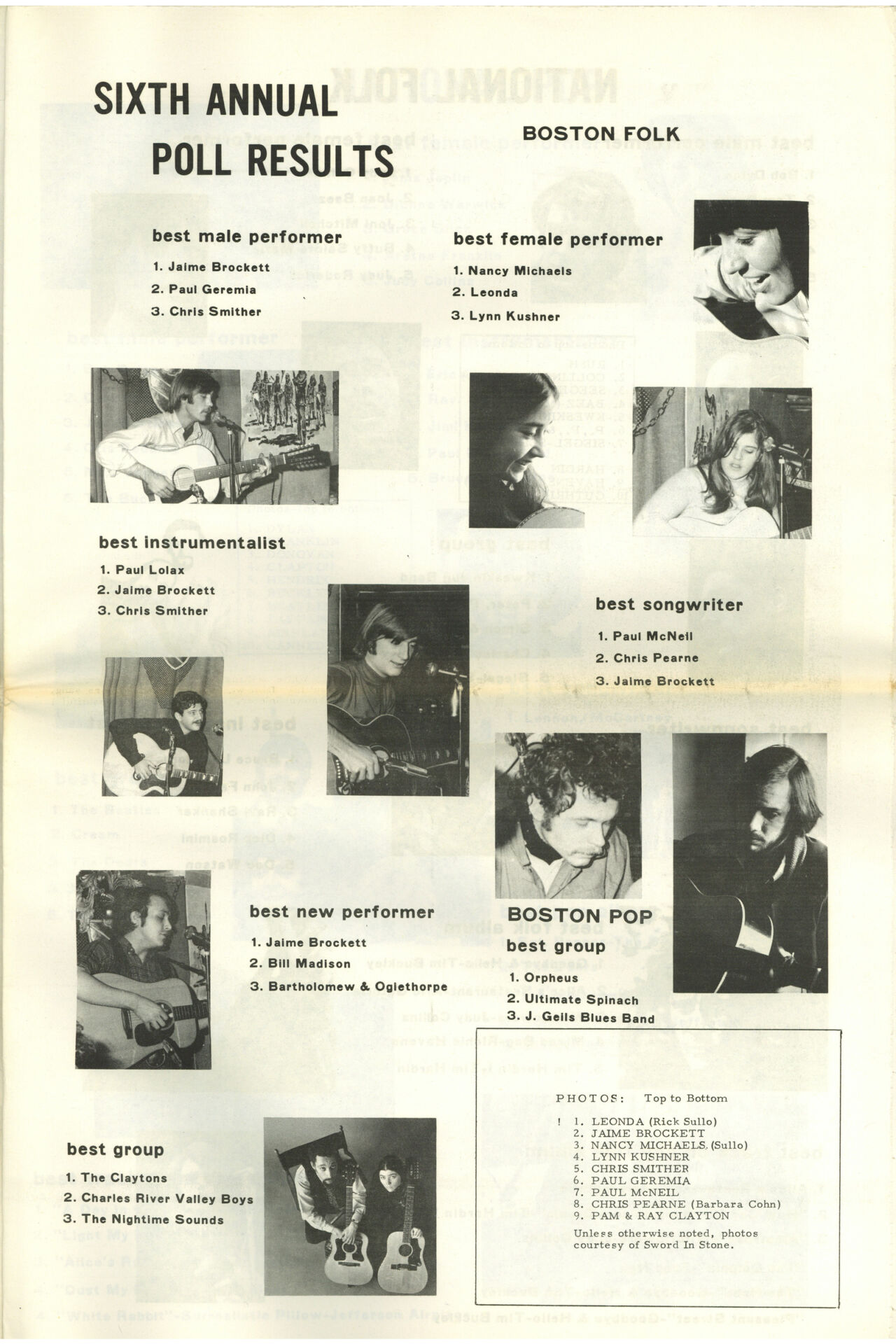

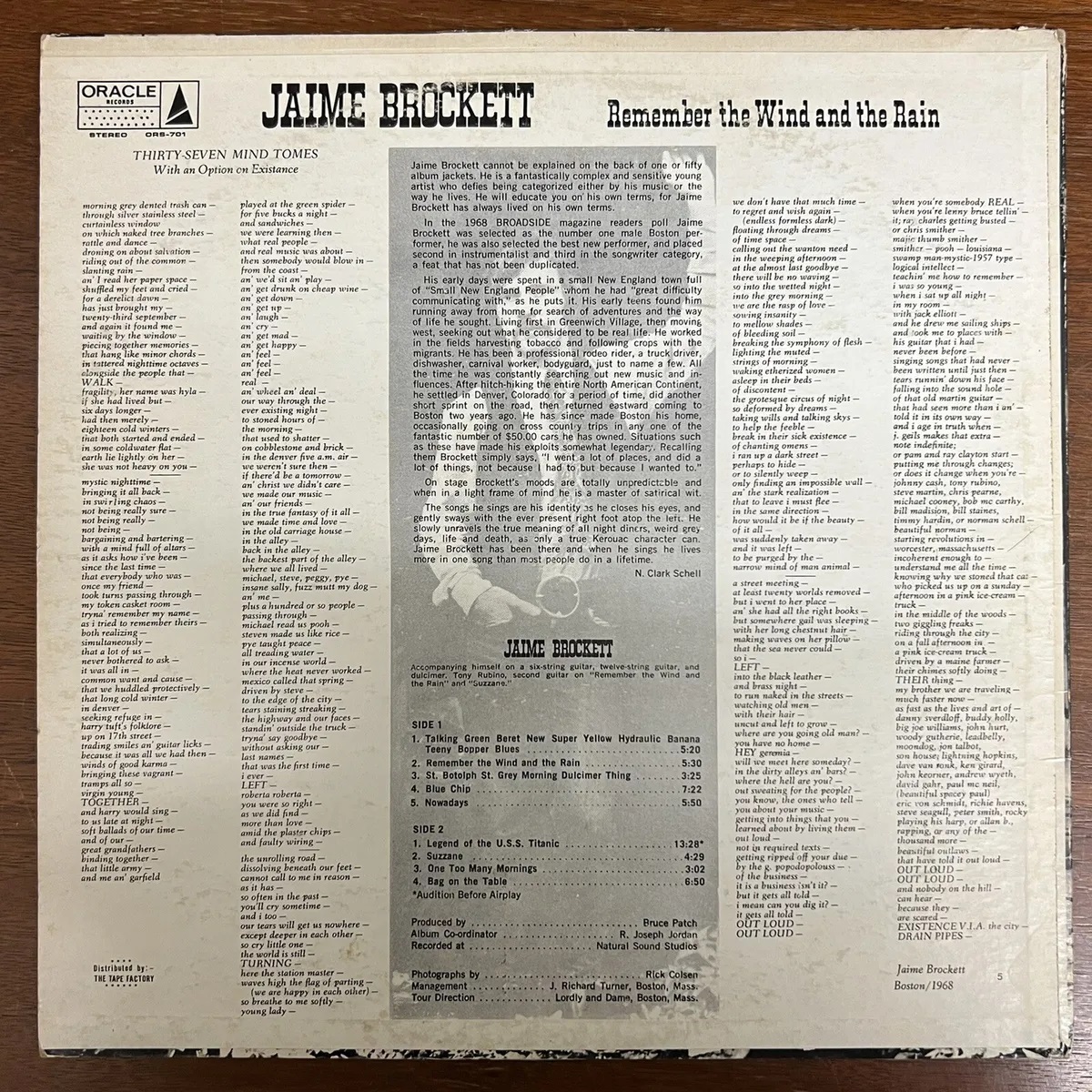

That same year, Oracle Records released his first album, Remember the Wind and the Rain, which included “Black Beauty,” an original composition written by this reporter. More importantly, it contained his folk-rap version of Leadbelly’s “Ballad of the USS Titanic,” the cut that would catapult him back-and-forth across the country like a pinball. It would also get him in trouble. One of the song’s lines, concerning “Jewish people trading wives and Cadillacs,” resulted in a stern letter from then-ADL President Justin J. Finger, accusing him of “foisting hoary canards.” He stopped playing the song around ’73.

In ’72, Capitol Records apparently thought he was taking too long to finish his second album, Jaime Brockett II, and released it without his authorization. It included several unfinished cuts. Abandoning Capitol, he said, “The hell with this. I’ll just live off my live shows.”

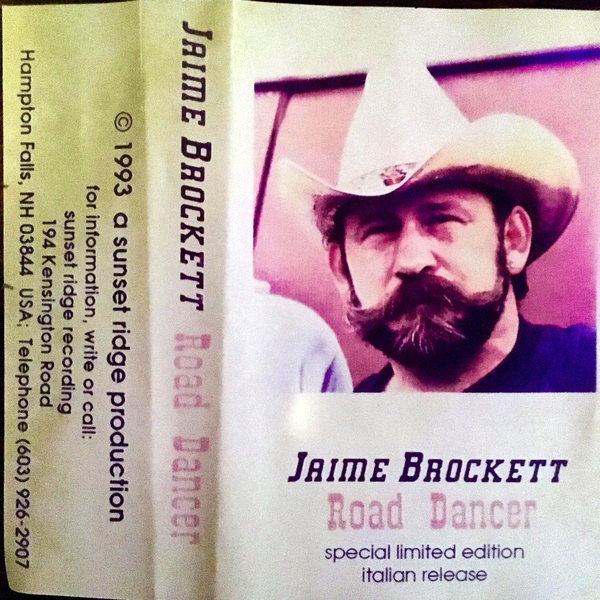

And he did, at the rate of at least 200 gigs a year for close to a half-century. Like Kerouac, a major influence he and I share, he roamed this “great groaning continent” in his tan van, “Old ’77,” playing concert halls, gymnasiums, coffeehouses, and colleges. And in all that time, as he sings on his deeply personal Italian-release, Road Dancer, “I never once changed my load.”

I’m sittin’ drinkin’ in Jaime’s kitchen with Eric “The Snake” Gulliksen and my wife Kathe. It’s the wee hours after a gig Jaime booked for us in Springfield, Vermont, a 45-minute drive from here. On the way we passed a giant pink doughnut with a bite taken out of it. I thought I was having a flashback, but it turns out that Springfield was the winner of the coveted “Home of the Simpsons” award, a competition among cities named Springfield, largely because of its nuclear reactor, prison, pub, and bowling alley.

Old ’77 is still parked right outside. Half Bondo, everything in it has been replaced at least twice. He claims he’s driven it over a million miles, and I don’t doubt it. He’s a complex man and a true outlaw balladeer, but he’s not a liar.

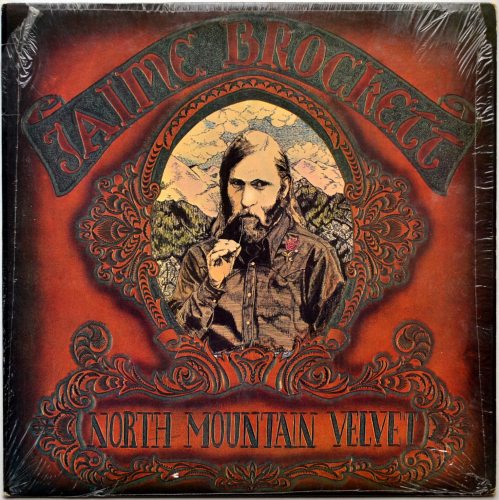

In the year ’77, he recorded North Mountain Velvet, which he considers his best effort. Unfortunately, it was released without fanfare by Adelphi Records: Insufficient promotion and distribution resulted in sluggish US sales, although it did well throughout Europe.

As Richard Wagamese, Ontario’s revered Native author and story-teller, wrote, “All that we are is story.” And man, what a story is Jaime Brockett.

When he left his Westboro home at the age of 16, he rented a cheap room that existed in approximately the same space later occupied by the stage of the legendary and too-soon-shuttered Old Vienna Kaffeehaus, where I opened for him one night. He arrived backstage with a guitar case, a dulcimer case, and a violin case. I said, “I didn’t know you played fiddle.” Wordlessly, he opened that case to reveal a bottle of whiskey nestled in a perfectly whiskey-bottle-shaped felt-lined indentation. He had had it specially made.

Jaime’s a collector. His recording studio is accessible only by a narrow and angular passageway through over 32,000 vinyl albums. On his desk is a wooden box full of doorknobs. Dozens of old padlocks without keys adorn his window sills. And here’s a box of keys without padlocks. And here, a stack of partially-used plastic-wrap boxes, each one discarded in frustration because he could not locate the torn-off end of its roll. The only thing here you might find in a relatively normal collector’s home is a glass case full of Red Sox memorabilia, but Jaime’s never aspired to normalcy, nor could he achieve it if he tried.

Here’s a story: During his relative youth, he and a friend were driving to Mexico. They had no money and had run out of food, except for a fruitcake that had been languishing in the back of the van since he’d been given it many months before. They both hated fruitcake, but rather than starve, they opened the can. Jaime sliced it up with his switchblade, the only knife they had, and they ate all they could. Sometime later, they were in a Mexican bar when a trio of locals began making fun of them. The gringos ignored them and continued drinking, until his friend had to go orina. Jaime watched as, a minute later, the tres amigos rose and also entered el baño. Jaime waited for long minutes but no one came out that door, so he got up and went in it. There he found his friend backed into a corner by the locals, one of whom held a knife. Now, Jaime hates violence, but he felt he had no choice but to whip out his switchblade and push the button.

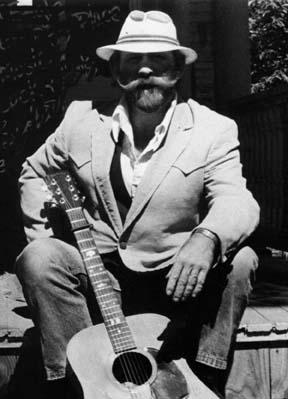

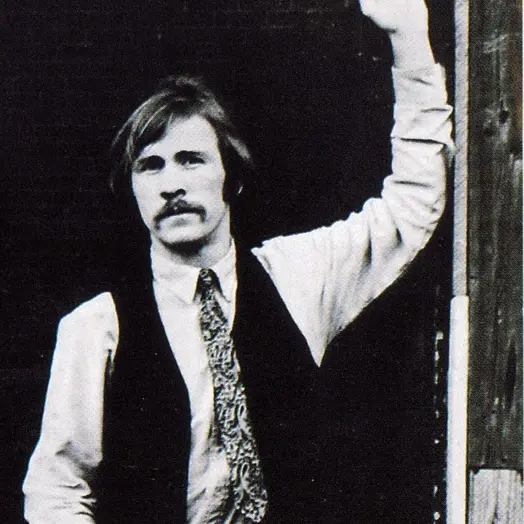

Before I go on, let me explain a couple of things. Jaime is not tall, and not exceptionally broad, and he felt he needed to “level the playing field” when defending himself against bigger, tougher guys. Hence the switchblade. But now, to give you the full visual of this, please imagine a not-tall person with a big mustache that makes him look like Yosemite Sam, pushing and re-pushing his knife’s button, but to no avail. Seems he forgot to clean the blade after the fruitcake. The Mexicans had to laugh, the knives were put away, and they all sat down together.

In another state, Jaime was in a bar when a bigger, tougher guy started picking on him. Jaime wasn’t holding a shiv: He had a set of metallic knuckles in his pocket, and he hit the guy in the jaw with them. The guy went down unconscious and had to be carried out.

“Stupidly,” says Jaime, “I stayed in the bar, long enough for the guy to come back with a cop, who wanted to know what I hit him with. I said, ‘Hey, it was just a lucky punch!’” Long story short, the cop found the knucks and Jaime spent the night in jail. He was arraigned in the morning, and ended up walking free. Why and how, you ask? Because the state law prohibited brass knuckles, and Jaime’s were aluminum.

In 2000, he produced Oroboros, my first solo CD, in Hampton Falls NH, and we shared a hotel room for a few nights. He snored loudly, talked in his sleep all night, and woke me at sunrise bellowing some hellish song I’ve purposely forgotten. On the last night of our stay, we bought a pizza and placed it on my bed. I’ve forgotten why, or even if there was a reason, but with his hunter’s knife he proceeded to stab that pie, not to mention the box, my blankets, sheets, and mattress. The next day, he presented me with one of his stock business cards on which was printed:

Mr. Jaime Brockett wishes to apologize for his behavior

on the evening of ______,19___.

Beneath that was a blank line on which he would specify the nature of the misbehavior, in this case:

“Snoring, sleep-talking, bed-stabbing & loud singing.”

It won’t be long until dawn. Before we turn in I ask him how he feels about his success, given that he’s made it under his own terms, in accordance with his own principles.

He shakes his head and replies, “Success is failure with a better class of women.”

I love this guy, in spite of – and because of – his compulsive iconoclasm.

And as his mother, bless her heart and soul, once said, “He means well.”

(by Stephen B. Martin)