Inn-Square Men’s Bar

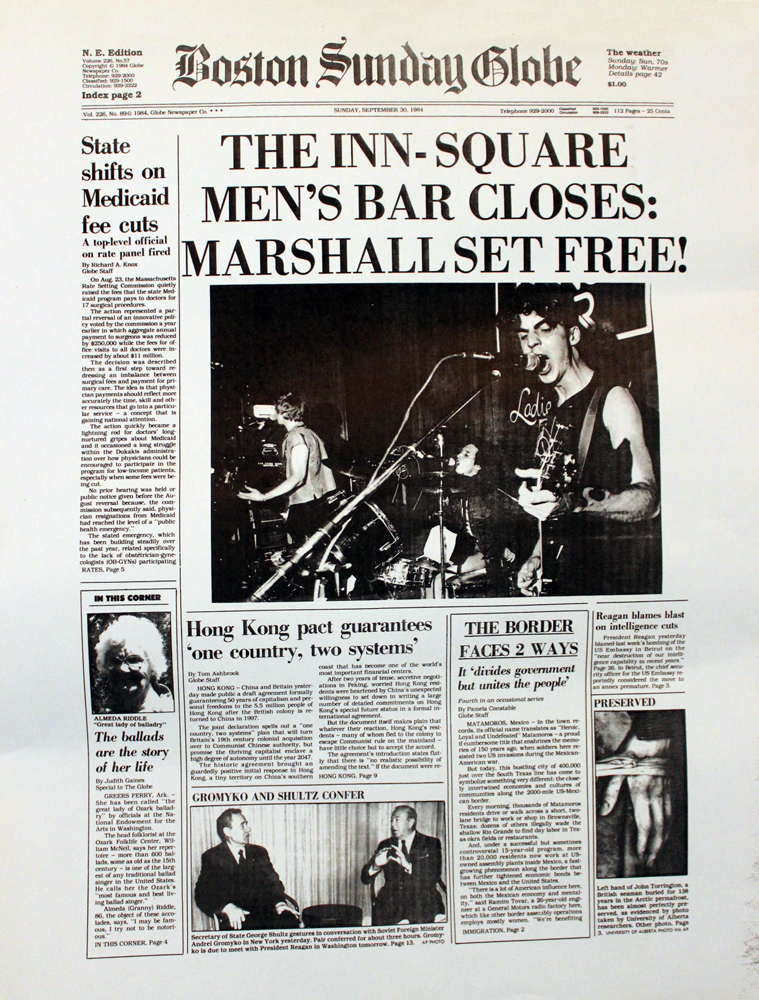

With its nondescript exterior, luxury-free interior and a name that revealed its decidedly blue-collar roots, Inn-Square Men’s Bar was as unassuming a venue as there’s ever been in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but it was among the area’s top spots for live music between the mid-‘70s and mid-‘80s, when radio moved from soft rock, prog rock and yacht rock to punk, postpunk and new wave. “It’s a Cambridge bar rather than a Boston music place,” James M. Barber of WHRB told The Harvard Crimson in 1984, noting that the venue had a welcoming, laid-back vibe and patrons of all ages.

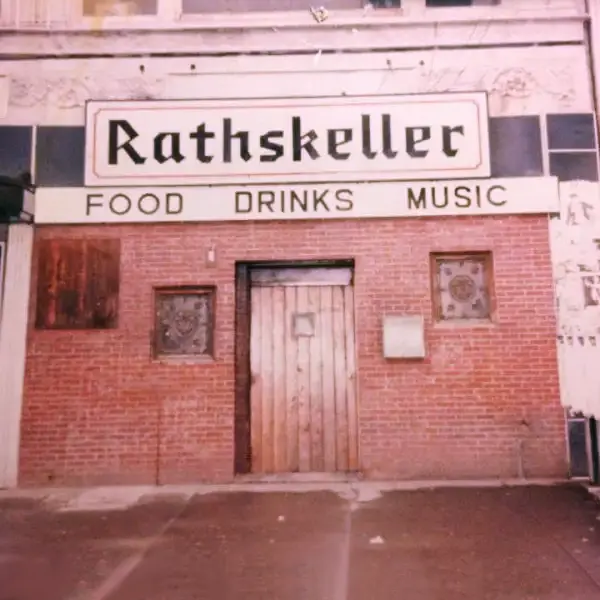

Its barroom essence aside, however, Inn-Square turned into much more than just another watering hole, especially after WBCN made it the site of the First Annual Spring Rock ‘n’ Roll Festival in 1978 (won by La Peste and renamed the Rock ‘n’ Rumble the following year). Its unique significance on the local scene was further confirmed in 1979 when a Boston magazine readers’ poll named it “Best Neighborhood Bar”; it was voted “Best Dance Club, Neighborhood” in ‘82 and “Best Bar for Live Music, Rock” in ’83. Though Inn-Square didn’t host nearly as many nationally and internationally acclaimed acts as other small venues in the area, most notably The Rathskeller and Jonathan Swift’s, it was one of the hottest places to see local bands, including several that eventually cracked the national consciousness, among them ‘Til Tuesday, Mission of Burma, The Del Fuegos, O Positive, Robin Lane & The Chartbusters, Nervous Eaters and The Stompers.

BACKROUND, LOCATION, OWNERSHIP, “LADIES INVITED”

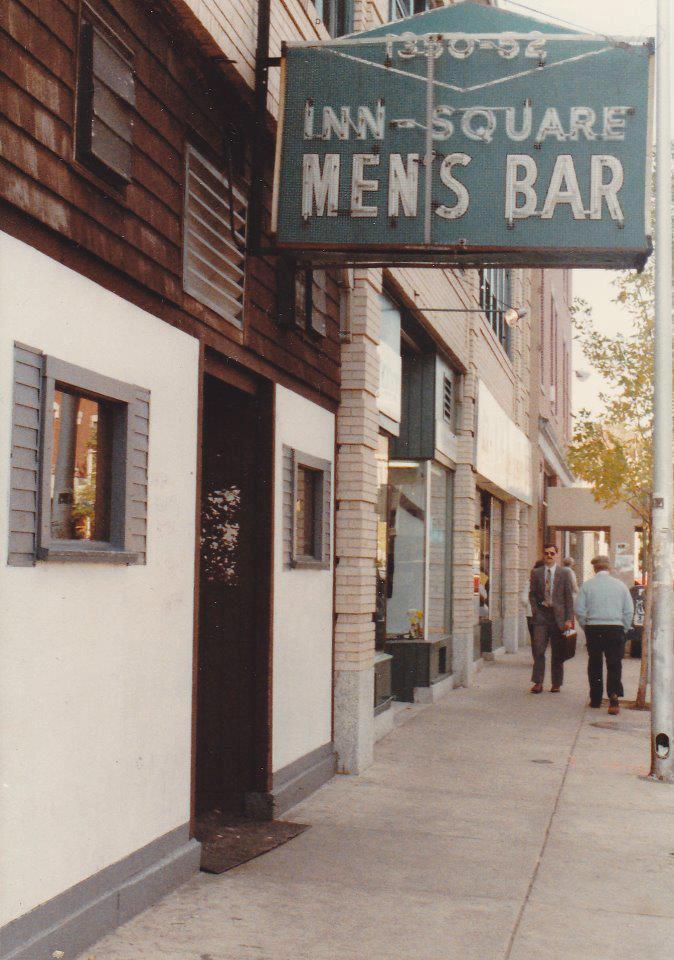

Located at 1350-52 Cambridge Street in Inman Square, Inn-Square Men’s Bar opened in 1964 and was frequented by Cambridge Public Works Department employees. Open from 8am to 10pm, it didn’t allow women at the time, as its name made perfectly clear. “It was basically a men’s meeting place,” former Inn-Square owner Marshall Simpkins told Vinyl Lives in 2022. “They had a rule in the Department of Public Works that as soon as you finished your job, you were done for the day. So the guys would get in there early. Sometimes they’d be done by noon and they would come into the bar, have lunch, and stay ‘til like three or four. That was like a standard thing.” The bar shared a wall with the S&S Restaurant, which opened in 1919, and Legal Seafoods opened its first restaurant nearby in 1968 (an outgrowth of Legal Cash Market, a grocery store that opened in 1904).

When Simpkins and his business partner Harvey Black took over Inn-Square Men’s Bar in ’74, the most popular venue for live music in the neighborhood was Joe’s Place, where Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band appeared in January that year, and the bar’s business was at a low; the DPW had extended the workday until 3pm, meaning fewer city workers dropped by and those who did usually didn’t stay as long as they did before. “Business was definitely down but it seemed like a good time to have a bar,” Marshall told Vinyl Lives, noting that the early ‘70s was when lines at the gas pump were notoriously long and inflation was high. And adding live music made a lot of sense, given Simpkins’s particular background; after graduating from Boston University in 1963, he was a film coordinator at WFIL in Philadelphia, home of American Bandstand, and hosted dances in and around Philly. He’d also worked for Crawdaddy, the first American rock magazine (founded in 1966, a year before Rolling Stone).

One of the first things Simpkins and Black did after securing the space was add “Ladies Invited” to the wording on the green metal sign out front in an effort to “make sure that women were allowed and comfortable,” Simpkins told Vinyl Lives. Having spent their every last dime acquiring the space, it was a clever and affordable fix, but that wasn’t the end of their equal-opportunity efforts; they also made changes to the staffing to create a more balanced mix of men and women tending bar and serving food. To accommodate performers and their audiences, they added a small stage opposite the bar (which was the longest in Cambridge at the time) and a table with red-topped, lunch-counter style stools in front of the stage. Behind the bar was a TV on a shelf, neon signs advertising Budweiser, Narragansett, Guinness and Miller Lite and red letters on a wooden sign that read “Positive Proof Required.” A space in the back of the bar became the green room and Simpkins kept an office near the rear door, which opened onto Hampshire Street.

GROWING POPULARITY, CLIENTELE

Soon after Simpkins and Black took the reins, Inn-Square became one of the best-known venues in Cambridge for live music, particularly rock and blues, though folk act and vocal groups also appeared. “Owned and managed by Marshall Simpkins, the Inn-Square was almost too good to be true: a small, warm neighborhood bar with good taste in music,” wrote Doug Simmons in The Boston Phoenix, calling it “a triumph of personality – a kind of honky-tonk that was perfect because of its imperfections.”

The clientele tended to be older and mostly locals during daylight hours but younger and from all over the area after nightfall, when Inn-Square “transformed into a hard-rock bar,” according to one former bartender, Bobby Keay. “It was a very, very unique place,” he told Vinyl Lives. “The television was a big black and white, up in the left-hand corner above the bar. The ‘remote control’ was a ladder; you had to climb up a ladder to tune it, turn it on or change stations. During the day, some of the regulars down at the end of the bar would want The Three Stooges on, so we’d put that on for them.” The close relationships between the Inn-Square staff were also key to the venue’s unique atmosphere, Keay said. “We all went out together and did things together,” he told Vinyl Lives. “It was like a real family during the day and more of a business enterprise at night.”

NOTABLE APPEARANCES, CLOSING

Simpkins handled all the bookings himself, bringing in the most popular acts on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays and paying them to play, while those on other nights would play for the door. The first artist to appear was folk legend “Spider” John Koerner, a frequent act at Cambridge’s Club 47 in the ‘60s who actually helped design an early version of the Inn-Square’s stage. One of the first national groups to take the stage was The McGarrigle Sisters (Montreal-based singer-songwriter duo Kate and Anna McGarrigle), who caught an Inn-Square show and signed up to perform (with Bonnie Raitt sitting in). Other national acts that played Inn-Square over the years included The Fabulous Thunderbirds, J.B Hutto & The New Hawks, George Thorogood, The Iron City Houserockers, The Dream Syndicate, Johnny Copeland and Garland Jeffreys. The most noteworthy non-musical act was George Carlin, who appeared in November ’81.

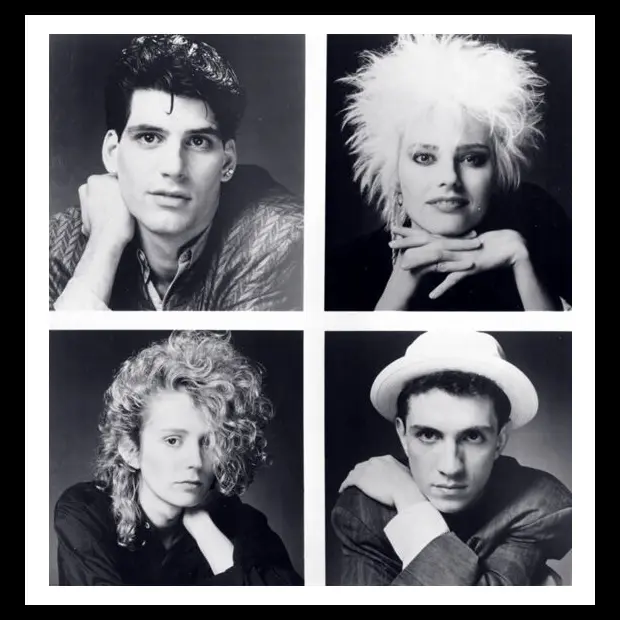

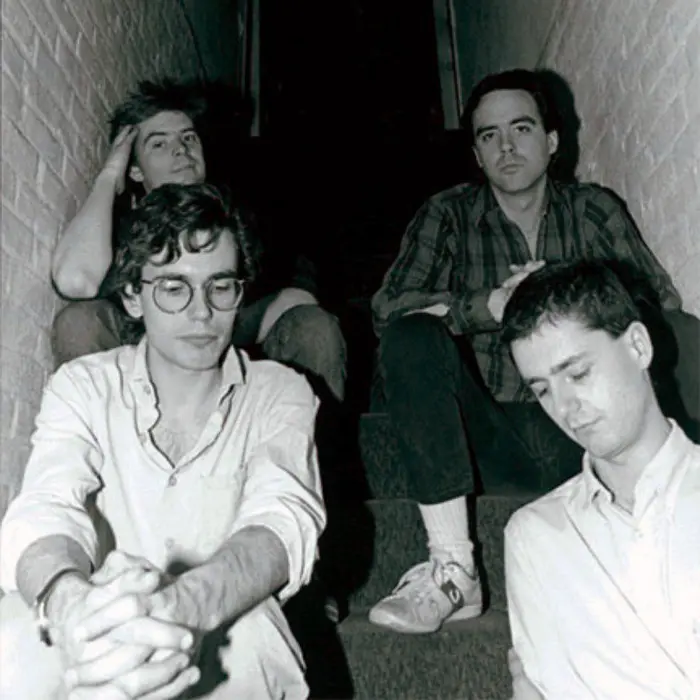

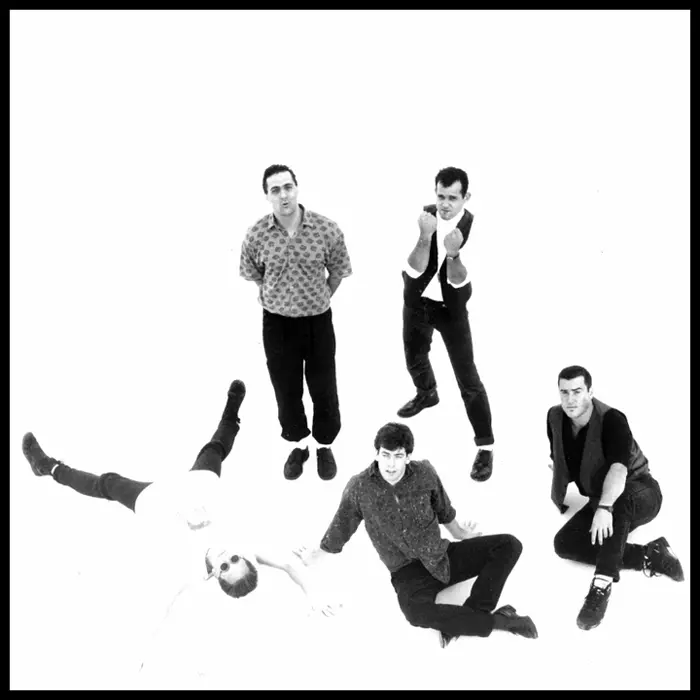

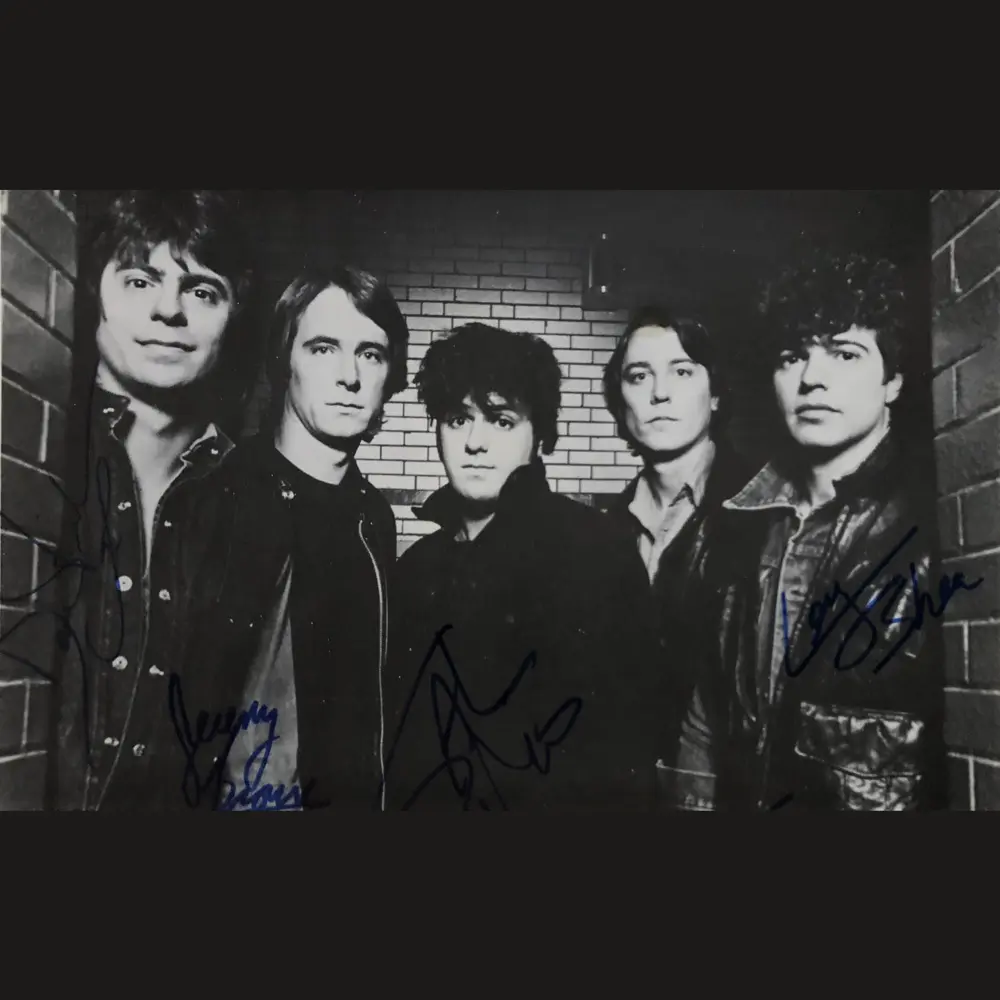

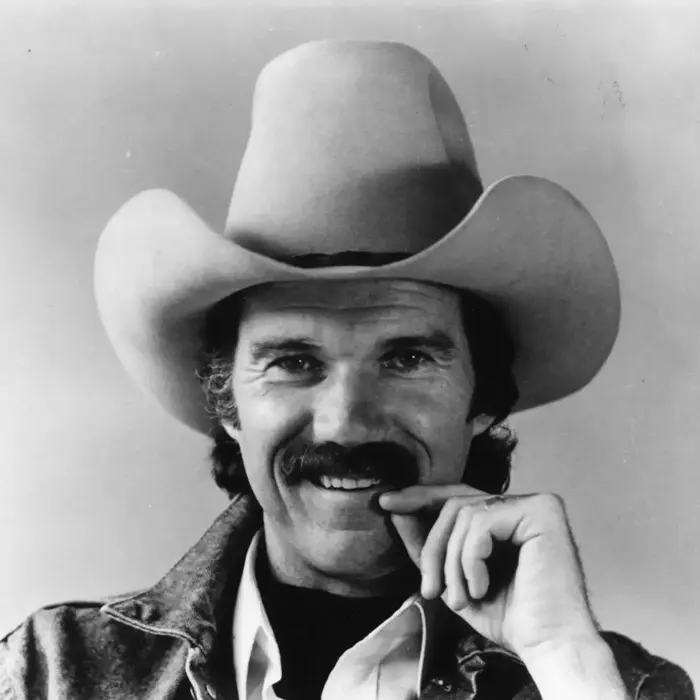

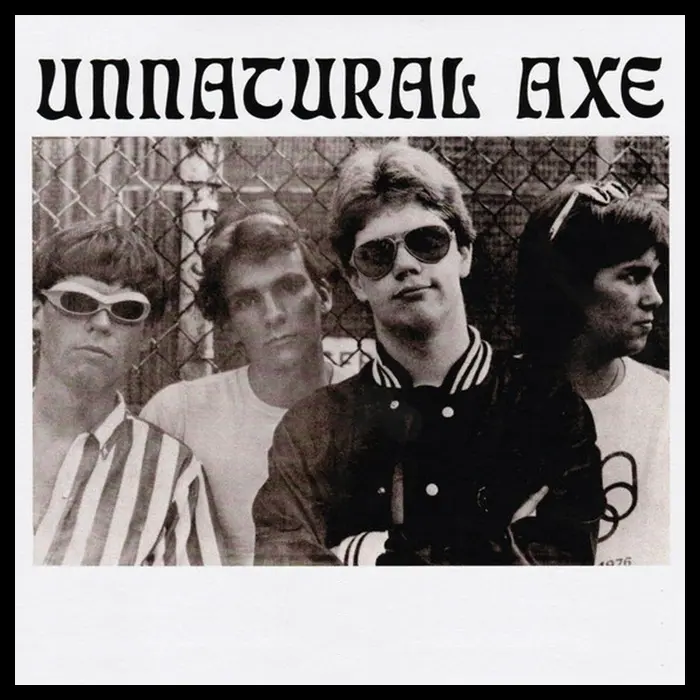

The list of Cambridge-, Boston- and New England-based bands that played at Inn-Square reads like who’s who of the local scene between the late ‘70s and mid-‘80s: Robin Lane & The Chartbusters, The Del Fuegos, Lou Miami & The Kozmetix, Mission of Burma, ‘Til Tuesday, Didi Stewart & The Amplifiers, Girls Night Out, Dangerous Birds, Barrence Whitfield & The Savages, The Thrills, The Incredible Casuals, The Neats, The Mechanics, The Stompers, The Young Snakes (with bassist Aimee Mann), Nervous Eaters, Treat Her Right, O Positive, Scruffy the Cat, The Mundanes, Unnatural Axe, The Blackjacks, Baby’s Arm, Classic Ruins, Lazers, La Peste, Robert Ellis Orrall, and John Lincoln Wright, among others.

The beginning of the end for Inn-Square was in the spring of 1984, when the building came under new ownership and the bar’s street level spot was put up for grabs. Simpkins considered moving the venue to the basement of the same spot, but realized that wouldn’t work because the neighboring S&S Restaurant had objected to the noise for years and wanted the bar gone altogether. As a second option, he requested that the Cambridge Liquor Licensing Board allow him to transfer his existing liquor license to a new location, the former Legal Seafoods building directly across the street; the city rejected the request.

The end came in October ’84, when the original liquor license expired and the board denied Inn-Square a new one. “The main ground for the license denial was the fierce opposition among area residents, who feared that the bar’s new location would increase noise in the neighborhood and require extra parking,” Mary C. Calnan, the board’s chair, told The Harvard Crimson at the time. Soon after Inn-Square closed, the S&S Restaurant acquired the space and Simpkins and Black moved on to other ventures. “We tried to get the old Legal building and the city wouldn’t allow it, so we just said ‘enough’ and got out of the business,” Simpkins told The Harvard Crimson. In 1985, Simpkins worked with Philadelphia-based promoter Larry Magid to produce Live Aid at Philadelphia’s JFK Stadium.

COMMENTS ON AMBIANCE, SIGNIFICANCE, ROSTER

Inn-Square employees, patrons and musical guests remember the venue fondly for its singular ambiance. “The vibe there was like no place else,” former bartender Keay told Vinyl Lives. “People got married there. We had drama there: somebody ran away with somebody, or somebody got shot. It was like a Damon Runyon kind of place, something you’d read about in the tabloids.” According to Stompers frontman Sal Baglio, the bar’s size and layout were part of its charm. “People were right up in your face in that place. It made you play right to the people and work hard,” he told Vinyl Lives. “And like many people before me and after me, one of [my] great memories is jumping up on that table that was just in front of the stage and doin’ a good Chuck Berry duckwalk up and down that thing.” A number of artists have commented on Inn-Square’s role as career a launching pad of sorts, including Robert Ellis Orrall, who told Vinyl Lives that it was “unequivocally” his “favorite place to play” and was an instrumental part of his band landing a deal with RCA in 1980.

Much of the venue’s success can be attributed to Simpkins, according to the various onlookers and artists who appeared, specifically his business savvy and willingness to try new things regardless of profit. “I think he would only play bands he thought were good, regardless of how much money they would bring. He did a good job of bringing a lot of bands you wouldn’t normally hear around town,” WHRB’s Barber told The Harvard Crimson. Didi Stewart credits Simpkins with helping her band Girls Night Out establish a strong following by making them a regular act shortly after they formed. “That’s what set him apart from everybody else,” she told Vinyl Lives. “It worked for the band, it worked for the audience, and it worked for him. I thought that was real vision.”

(by D.S. Monahan)