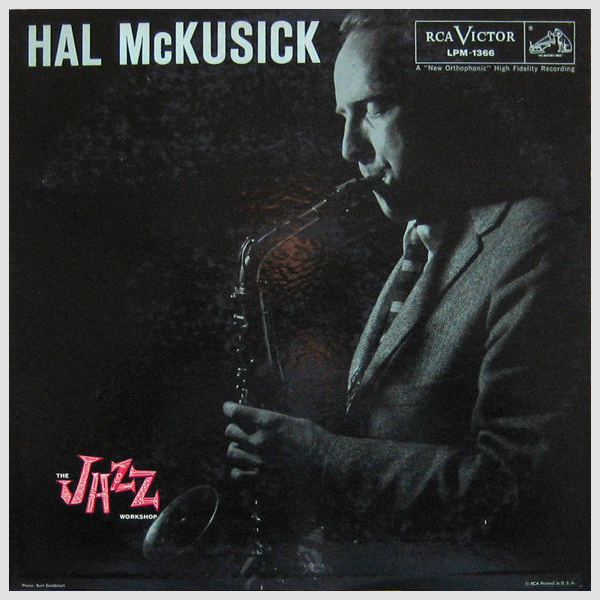

Hal McKusick

The phrase “Comparisons are odious” can be traced back to 1440, when it appeared in the poem “The Debate Between Horse, Goose, and Sheep.” It’s been used in various formulations since by big literary names from Cervantes to Shakespeare, and has continuing application in the world of jazz: Were it not for Paul Desmond, you’d probably know more about Harold Wilfred “Hal” McKusick, born in 1924, the same year as Desmond.

The All Music Guide to Jazz compiles “Music Maps” that depict the practitioners on particular instruments down through history of jazz; in the alto saxophone category of “Cool Jazz Innovators,” it lists Lee Konitz, Art Pepper and Paul Desmond, but McKusick deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as them. McKusick played clarinets as well, both soprano and bass, but he didn’t make the cut for the “Music Maps” sections on those instruments either.

MUSICAL BEGINNINGS, EARLY COLLABORATIONS

McKusick was born on June 1, 1924 in Medford, Massachusetts and grew up in Newton. As told to Marc Myers of the JazzWax blog, the move was occasioned by his father’s job as manager of Noble’s Milk Farm, back when Newton was still a relatively rural area. “We bred and raised horses,” McKusick said. He acquired his first reed instrument, a clarinet, as a Christmas gift. “I wouldn’t let it go,” he said. “I practiced for hours.” Taking lessons from an instructor named Frank Tanner, he learned to play clarinet and alto sax at the age of nine.

When he was 15, McKusick began playing at Old Howard Athenaeum, a burlesque house in Scollay Square (now known, post urban renewal, as Government Center). He subsequently formed his own band and began to play in a nightclub in Dorchester, backing a man whose schtick was throwing knives at his wife and shooting cigarettes out of her mouth. His mother put the kibosh on that career path when she showed up one night and found that her son had been substituted as the target. “One night the guy’s wife got sick, so he offered me an extra $5 to stand in for her,” McKusick said. “That was more money than I was making playing the job. What did I know at 15?” Later in his teens, he started playing with now-obscure bands (Don Bestor, Dean Hudson) and those whose names live on (Woody Herman, Les Brown), if only faintly at this point.

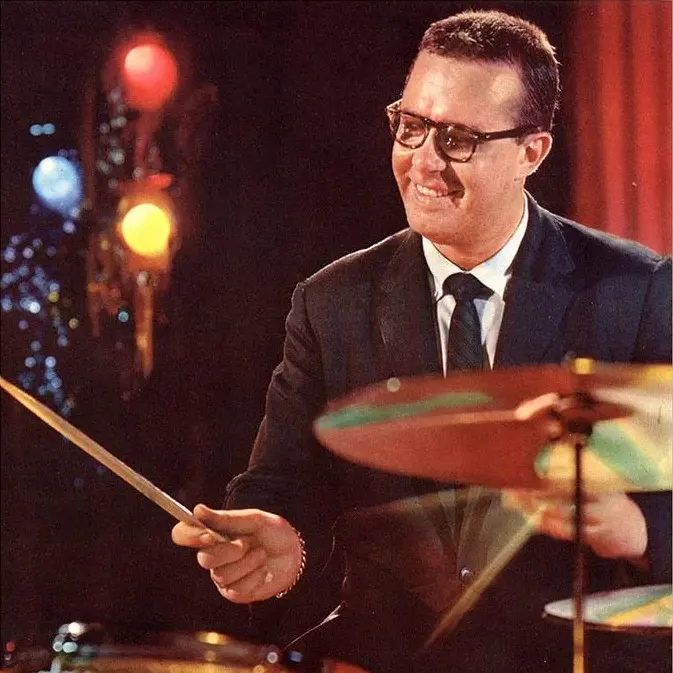

After World War II, he moved to the West Coast, where he played with R&B pioneer Johnny Otis and drumming legend Buddy Rich, among others. He spent significant amounts of time with two bands that were way stations for, in the words of jazz pianist-composer-critic Leonard Feather, “young talent of the nascent bop school,” those of Woody Herman and Boyd Raeburn (1944). McKusick didn’t get caught in the bop undertow of Charlie Parker’s influence, however: Whitney Balliett, jazz critic for The New Yorker, said that his playing “bears a refreshing resemblance to Benny Carter” at a time when “nine out of 10 modern alto saxophonists are true copies of Charlie Parker.”

CLAUDE THORNHILL, GEORGE HANDY, ZIGGY ELMAN, JOE ALBANY

McKusick’s ability to swim against the current may have been aided by the time he spent as lead clarinetist with Claude Thornhill (1948-49). Thornhill’s book included (according to Feather) “a variety of classical, pop and jazz material” and a core group of his sidemen (among them Lee Konitz and arranger Gil Evans) formed the basis of the Miles Davis Birth of the Cool band.

McKusick collaborated with arranger George Handy in Raeburn’s band, but the two quit over a technical point that will strike non-musicians as quixotic: Raeburn was assigning solos meant for tenor Al Cohn to alto Johnny Bothwell, which McKusick and Handy felt made no sense. After landing in New York City following a gig in Boston, the two quit in protest and flew to the West Coast. They lived in a hotel for a while, getting by on temporary gigs; McKusick said he played with Ziggy Elman’s big band in San Francisco. Towards the end of 1945, McKusick moved in with pianist Joe Albany’s family in Los Angeles, bringing with him a double-breasted striped suit that a Chinese tailor had made for him in San Francisco.

In December of 1946, Albany and McKusick heard Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie live at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood and a few days later, when McKusick looked in his closet, his suit was gone. When he asked Albany if he had seen it, the pianist said, “I gave it to Bird.” Albany wanted to give Parker a gift to welcome him to the West coast and didn’t consider that McKusick might mind the misappropriation of his new clothes. “Strangely, though, he was right,” McKusick recalled years later. “We were so happy to be able to hear Parker in person. I was honored that he was wearing my suit at Billy Berg’s.”

BANDLEADER RECORDINGS, CBS, RETIREMENT, LATER ACTIVITY, DEATH

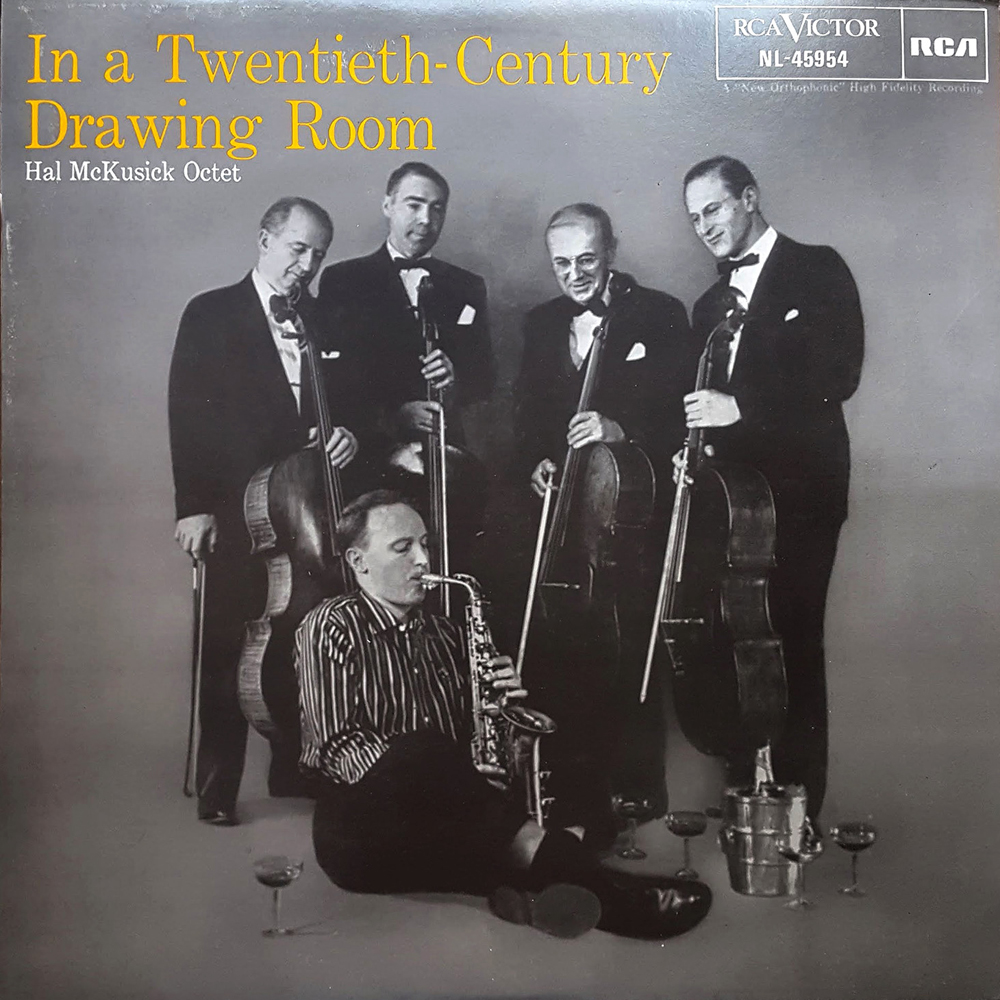

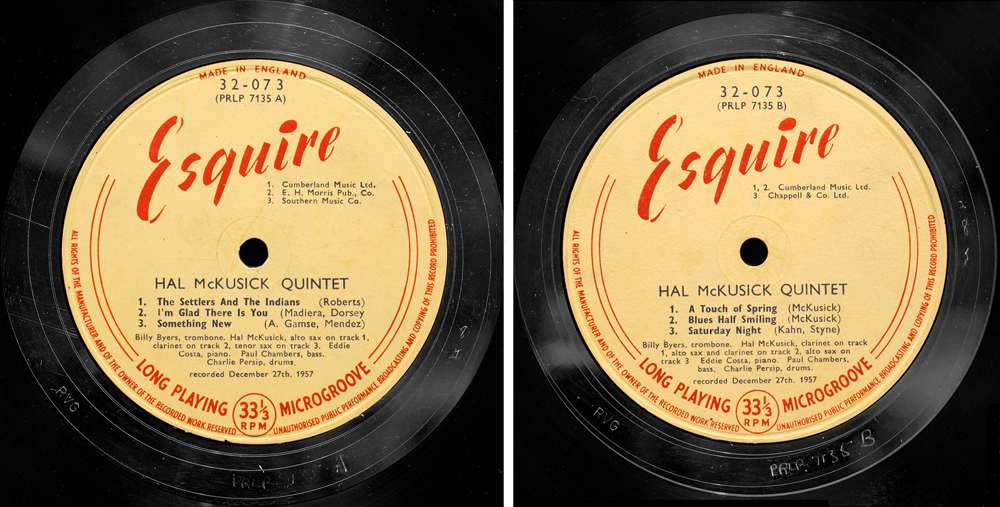

Between 1955 and 1958, McKusick recorded nine albums as a leader of a septet (four saxes plus rhythm), and it is through this material that I became familiar with his work by a random rotation on a streaming service. It holds up well against Desmond’s work with Dave Brubeck and others, and between the two it comes down to a matter of taste, like choosing between Benny Carter and Johnny Hodges from the prior generation of altos. Desmond composed and played what is said to be the best-selling jazz record of all time – Take Five – so it isn’t surprising that he is remembered today while McKusick is not.

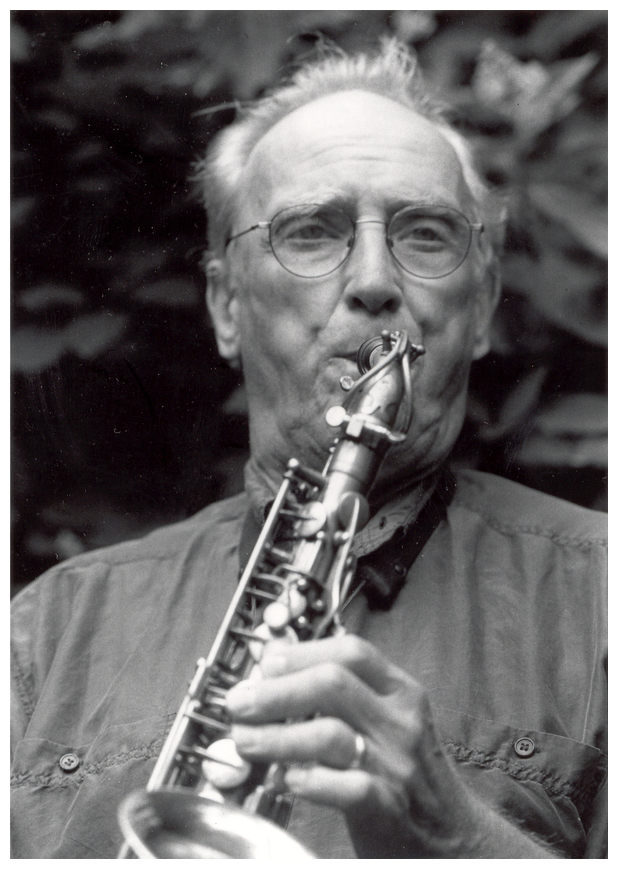

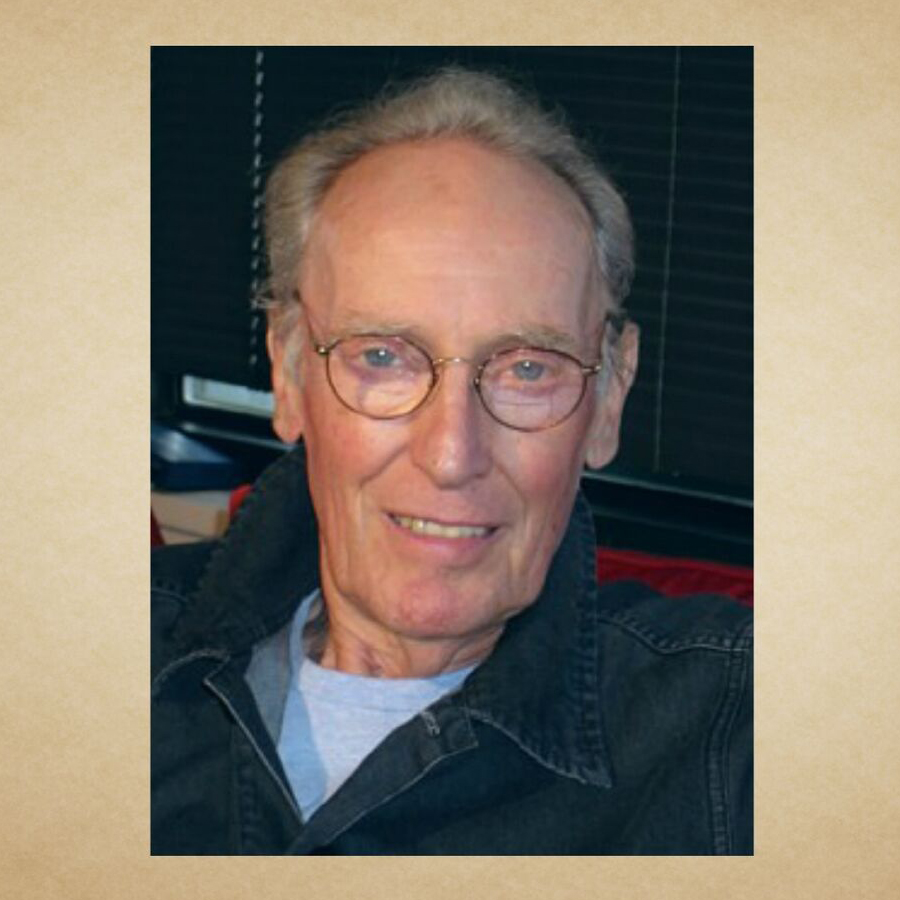

McKusick’s relative obscurity was probably the reason he opted for steady employment as a staff musician for CBS in New York from 1958 to 1972, and his occasional work writing jingles for commercials. He retired from performing to Long Island, where he kept himself busy teaching and woodworking; in the latter capacity, he was sufficiently talented to be the subject of an article in The New York Times, “Jazzman Notches 2nd Career in Wood Workshop.” He was also a licensed pilot.

Like Desmond, who had been a student journalist and once wrote an essay for the British humor magazine Punch (“How Jazz Came to the Orange County State Fair”), McKusick had an artistic side apart from his music; he appeared in the Edward Albee play “The Sandbox.”

McKusick died in 2012 of natural causes at the age of 87.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (2019, Oxford University Press), winner of Hot Club de France’s Book of the Year Award, Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (2023, Equinox Publishing) and the forthcoming Sax Expat: Don Byas (scheduled for publication in April 2025).