Avedis Zildjian Company

As any musician playing any practically kind of music will attest, Zildjian is as synonymous with high-quality cymbals as Steinway is with grand pianos, Gibson is with electric guitars and Marshall is with ear-splitting amps. And while the Massachusetts-based company has some competitors, most notably Paiste and Sabian, millions of drummers would insist that Zildjian has always been, to quote the company’s slogan, “the only serious choice.”

Overview

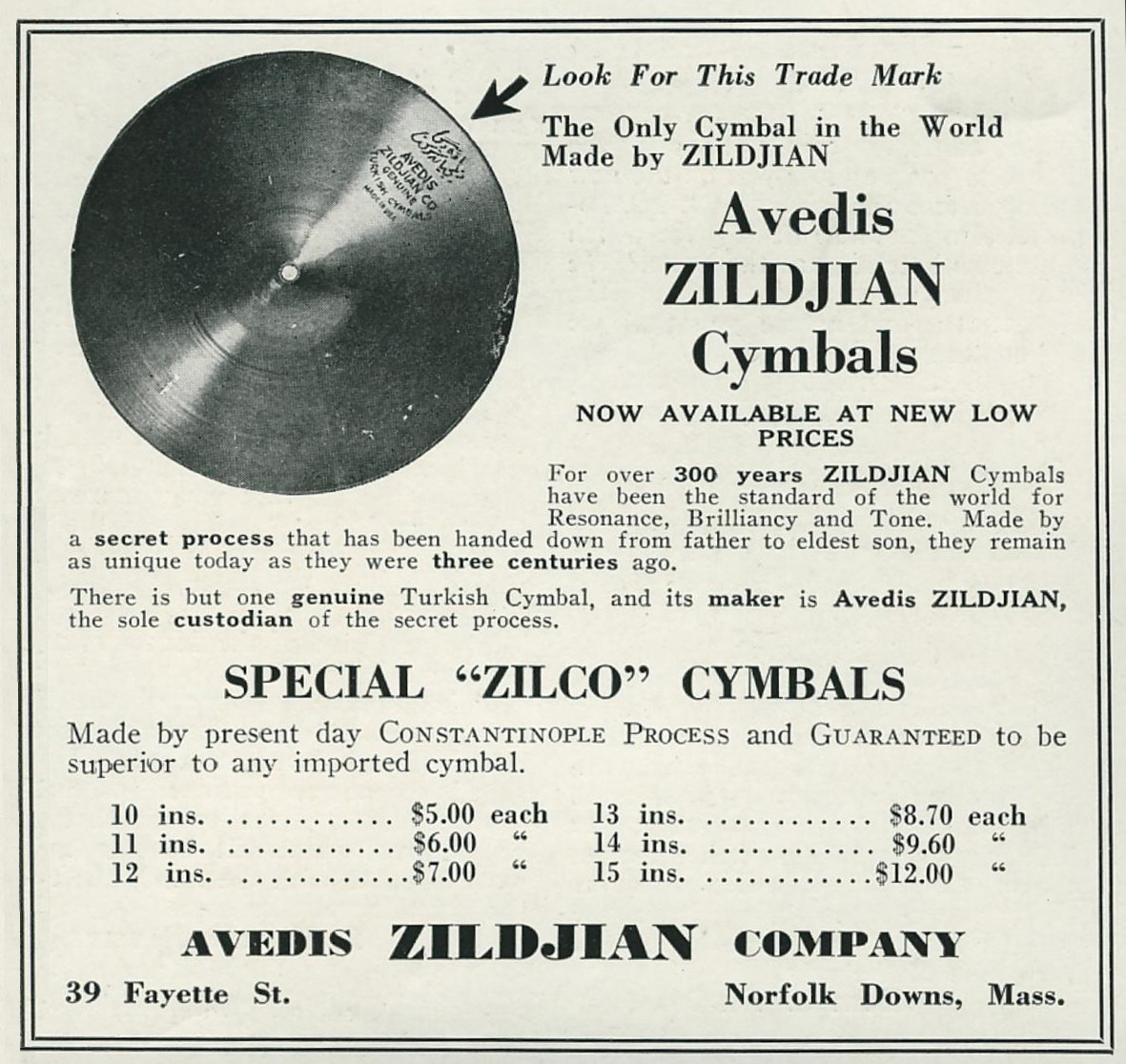

With a history spanning four centuries, Zildjian is by far the world’s oldest manufacturer of musical instruments (not only cymbals), a 15-generation-long enterprise that makes Paiste, founded in 1906, a relative teenager and Sabian, founded in 1981, a relative infant. It’s also the oldest continuously operating family-owned business based in the United States, Avedis Zildjian III having opened a workshop in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1928 and a foundry there in 1929, at the height of the Jazz Age.

Since then, Zildjian has gained an estimated 65% of the global cymbal market and been the industry’s leading innovator, literally inventing now-standard cymbal vocabulary such as “ride,” “crash,” “sizzle” and “splash” while creating products that provided the sounds drummers in the ‘30s and ‘40s said they heard in their heads. Though popular music has always been in a state of flux – morphing into today’s multi-genred mélange of jazz, swing, R&B, soul, rock, hip hop and EDM – Zildjian has remained the brand most associated with those golden circles of mysterious metal that punctuate songs, bedazzle audiences and create a passion bordering on obsession in drummers of all ilks.

Avedis I, Secret formula, First workshop

The company’s history begins in 1618 in Constantinople (now Istanbul), when 22-year-old Avedis I, an alchemist working in the court of Sutan Osman II (ruler of the Ottoman Empire), discovered the alloy formula for what became Zildjian cymbals. He made his discovery entirely by accident, while attempting to make gold (under the Sultan’s orders), which required forging metal that was flexible enough to be repeatedly heated, rolled and hammered; through that process, he found that a certain combination of tin, copper and silver was extremely durable and created a rich, robust, truly musical sound. “He was looking for gold and as far as I’m concerned, he found it,” said Paul Francis, Zildjian’s R&D director, in a 2018 interview with The New York Times.

Cymbals had been used across Asia and the Middle East for over 2,000 years by the time Avedis I was born – mostly in religious ceremonies and military music – but his alloy represented a revolution in terms of their strength and sound quality. Osman II was so impressed that he made Avedis I one of the court’s official instrument makers, crafting cymbals for the janissary (an elite military corps), calls to prayer, royal events like feasts and weddings and the belly dancers in the Ottoman Imperial Harem, who wore finger cymbals.

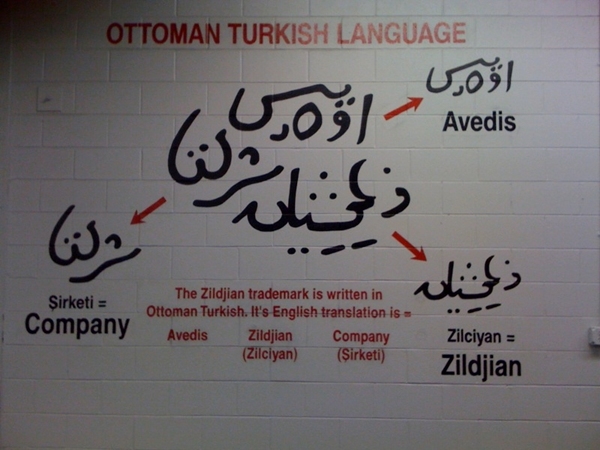

In 1622, four years after Avedis I had produced his first cymbals, a new sultan, Mustafa I, gave the 26-year-old artisan 80 gold coins and the name “Zildjian,” meaning “son of a cymbal maker” (“zil” being Turkish for “cymbal,” “dj” being Turkish for “maker” and “ian” being an Armenian suffix for “son of”). In 1623, when the sultan allowed Avedis I to leave the palace, he established his own cymbal business, opening his first workshop in Samatya (the Armenian sector of Constantinople). Over the next 30 years, he further developed the formula and production process, both closely guarded secrets to this day.

Cymbals’ introduction into opera, classical

In 1651, Avedis I’s eldest son, Ahkam, began running the Samatya workshop, his father having passed the secret alloy formula to him verbally; it was not written down until the early 1940s. Historians have uncovered very little about the Zildjians and their business for the next 200 years, but by the late 1600s composers had begun incorporating cymbals into their work, the first known example being Nicolaus Adam Strungk for his 1680 opera “Esther.”

In the 1700s, Mozart and Hadyn included cymbal arrangements in some of their material and Beethoven, Berlioz and Wagner used an abundance of cymbals in their compositions during the 1800s, the latter two insisting that only Zildjian cymbals be used. By the mid-1800s, cymbals were thoroughly integrated into military bands and orchestras across Europe and the US.

Avedis II, Building a global brand

After Ahkam’s death, the secret alloy formula was handed down to several generations of male heirs and in the early 1800s Haroutune Zildjian passed it on to his son, Avedis II. In 1850, Avedis II built a 25-foot schooner to transport the first cymbals embossed with the family name to London for the Great Exhibition in 1851 (the first World’s Fair); Zildjian’s “Turkish cymbals,” as they became known, began drawing widespread acclaim among composers and percussionists worldwide following the historic event.

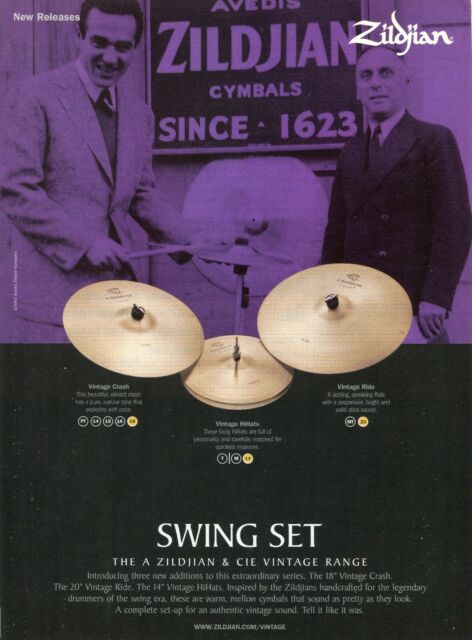

Avedis II died in 1865 and his younger brother Kerope assumed control of the company since Avedis II’s sons, Haroutune II and Aram, were too young to do so. Kerope introduced a new “K” series of cymbals, which are widely used to this day, particularly in classical and jazz. Over the next three decades, Zildjian won honors at multiple exhibitions – among them Paris (1867), Vienna (1873), Boston (1883), Bologna (1888) and Chicago (1893) – and by 1900 the company was exporting some 1,500 pairs of cymbals to orchestras per year.

Avedis III, Quincy foundry opening

Following Kerope’s death in 1909, Avedis II’s eldest son, Haroutune II, declined his birthright to take over the business, pursing law and politics instead, and his second son, Aram, was unable to do so since he’d fled to Hungary in 1905 after being part of an assassination attempt on Sultan Abdülhamid II. With the elder sons unavailable, two of Kerope II’s younger sons, Diran and Levon, were put in charge.

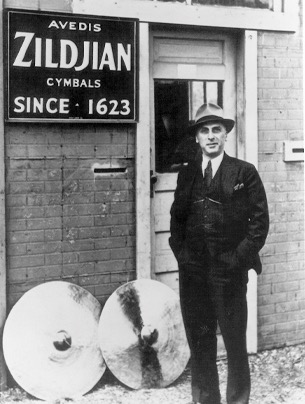

In mid-1909, 19-year-old Avedis III, Haroutune II’s son, moved to Boston – where a sizable Armenian community had been growing since the late 1800s following rampant persecution of Armenians in Turkey – and established a confectionary business, which he ran for 19 years. In 1927, his uncle Aram informed him that he was to become heir to the family business, but Avedis III had no interest in running the company at first. After considering the gigantic sales potential given the jazz boom, however, he agreed to take the reins. “I saw the possibility that even if there wasn’t a market we could create one,” he said in a 1975 interview with The Armenian Reporter.

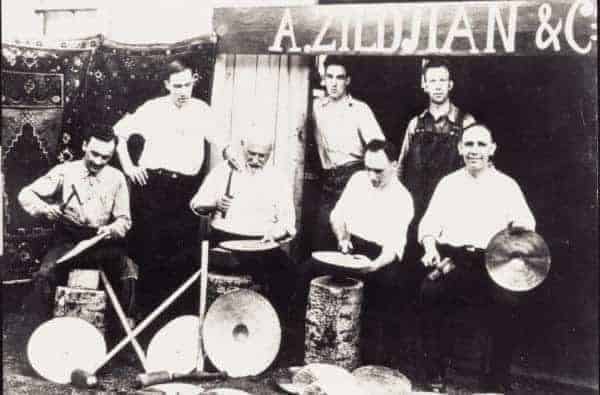

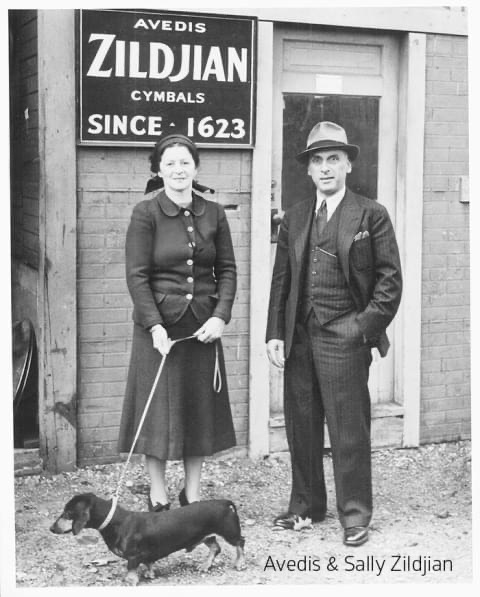

In 1928, Avedis III, his brother Puzant and his uncle Aram began manufacturing cymbals in Quincy, their workshop housed in a garage filled with old taxi cabs. In his memoirs, Avedis III wrote that they chose Quincy because it was near the sea, like Constantinople, and they believed salt water had a positive effect on the metal. In 1929, they established the Avedis Zildjian Company, its foundry located on Fayette Street in Quincy.

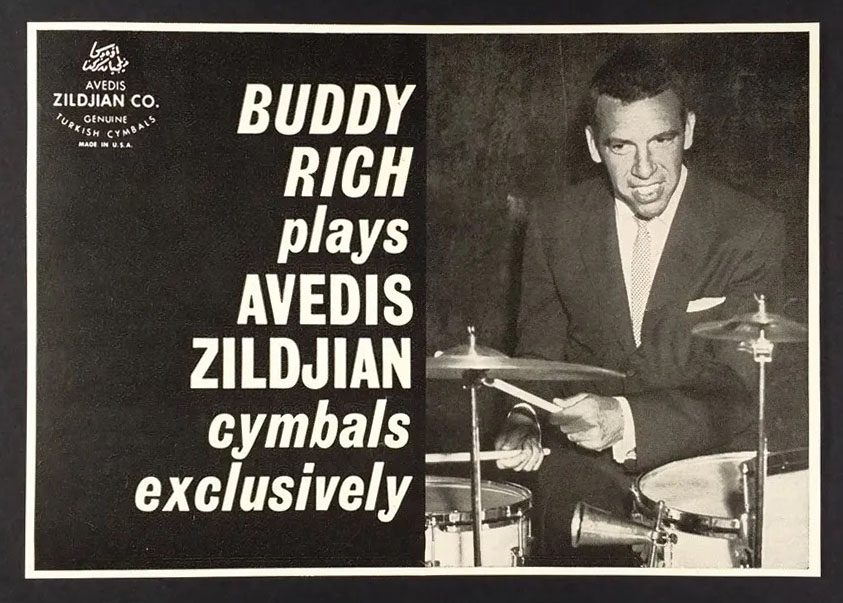

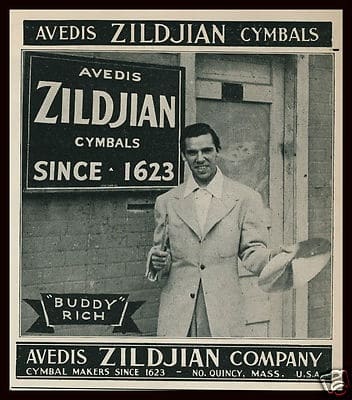

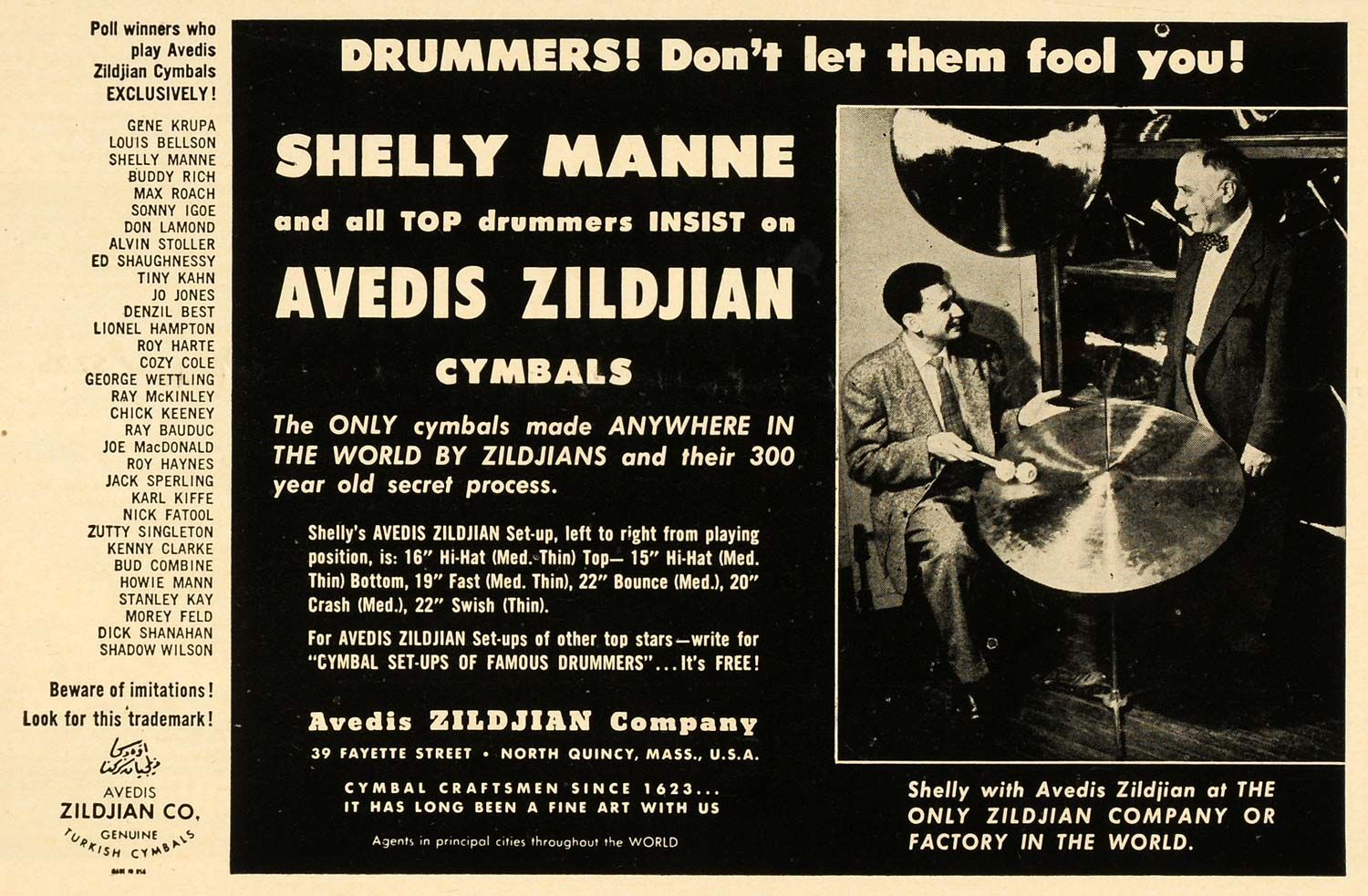

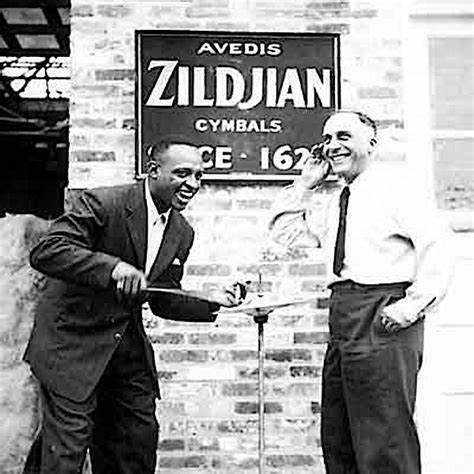

1930s: Early endorsements, Challenges

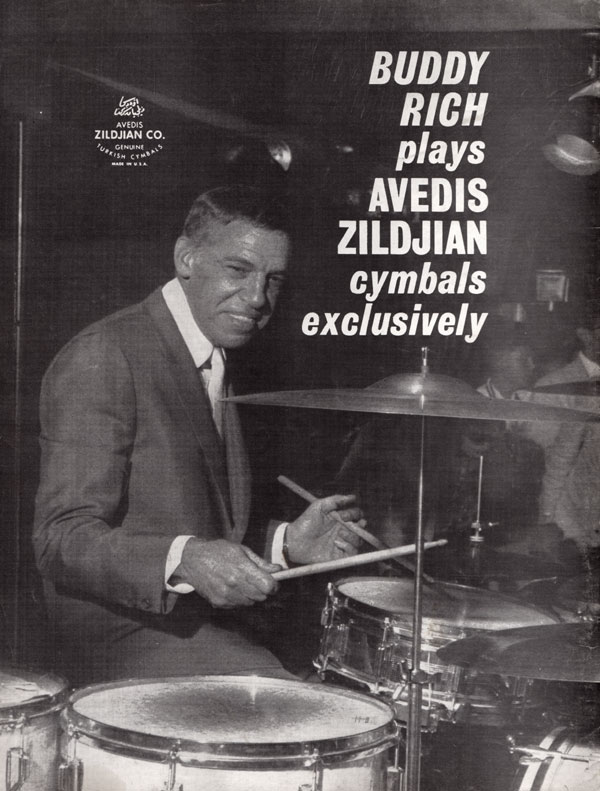

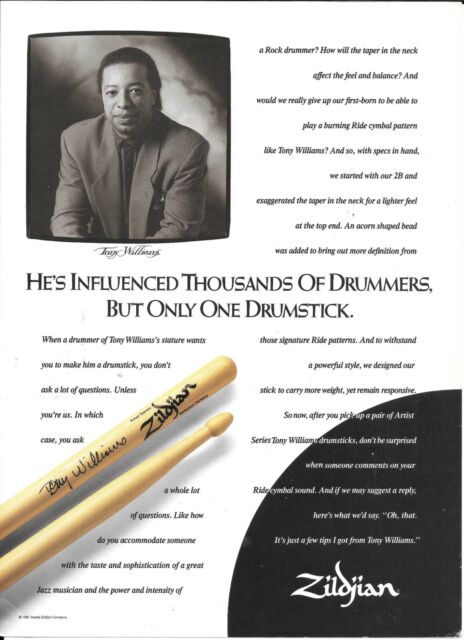

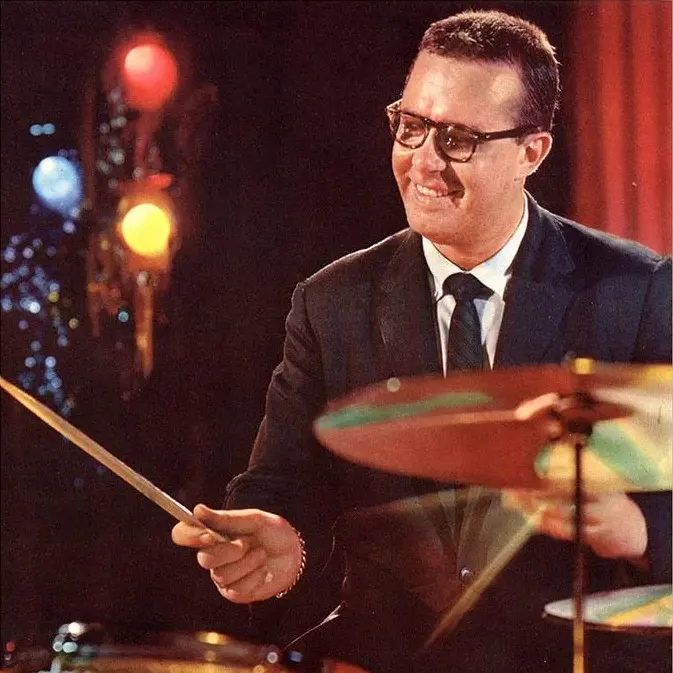

In the ‘30s, Avedis III and Puzant sought out well-known jazz drummers who were willing to endorse Zildjian and they developed close relationships with future legends including Gene Krupa, Chick Webb, Papa Jo Jones, Buddy Rich and Lionel Hampton. Their input resulted in Zildjian’s invention of cymbals specifically designed for use with drum sets; prior to Zildjian entering the US market, kit drummers used thick, marching-band cymbals since they were the only option. Many of the company’s earliest innovations – among them ride, crash, swish, sizzle and splash cymbals – were named by Avedis III; some later ones were named by his eldest son, Armand, the first American-born Zildjian, who began working in the factory’s melting room in 1935, at age 14.

Despite such high-profile supporters, however, Zildjian faced a number of challenges in the ‘30s. First, from 1931 to 1939, the US unemployment rate ranged from 16% to 25%. Second, Aram had cut a deal with Gretsch in 1926 that gave the drum maker distribution and naming rights to the Zildjian brand, leaving Zildjian marginally profitable at best; the company didn’t regain those rights until 1968. Third, a fire in 1939 leveled Zildjian’s original Quincy foundry, forcing them to move to a new location in the city.

1940s, 1950s

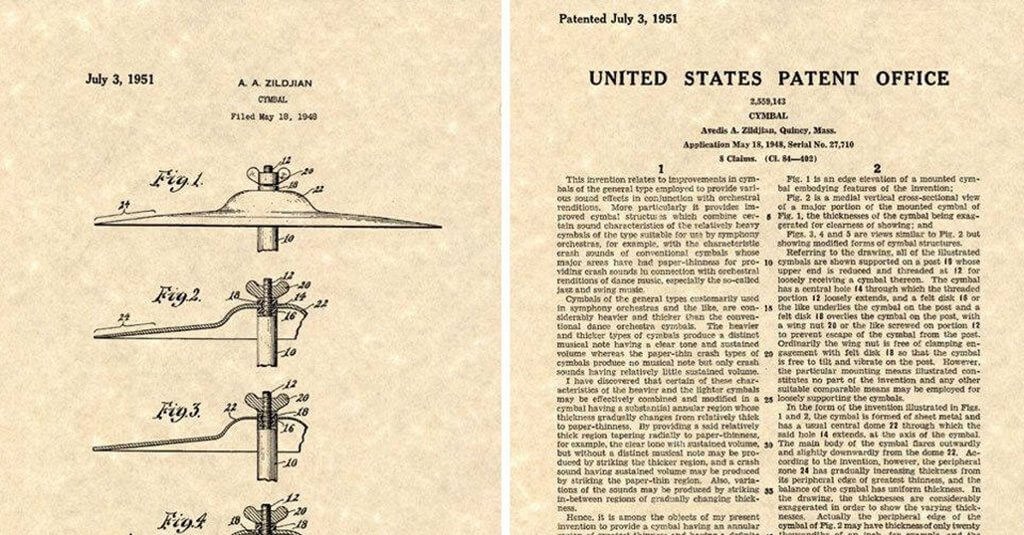

The ‘40s were also challenging for Zildjian and the company was on the brink of bankruptcy more than once during the decade. The first major threat came in early 1942, when the War Production Board began rationing tin and copper for the war effort; fortunately for the company, Zildjian was allotted enough of both to fill American and British military orders for cymbals. Both of Avedis III’s sons were drafted during World War II – Armand served with the Coast Guard in the Pacific and Robert served with the Army in Europe – and he wrote down the secret alloy formula for the first time in case they were killed, keeping one copy in the company vault and another in his home.

Immediately after the war, 24-year-old Armand began managing the foundry, arriving at the melting room around 5:30am every day; between each melt, he helped staff fill orders from the shipping room. His younger brother Robert earned degrees in philosophy and history from Dartmouth before joining Zildjian in his mid-20s as the head of international sales and marketing, among other roles.

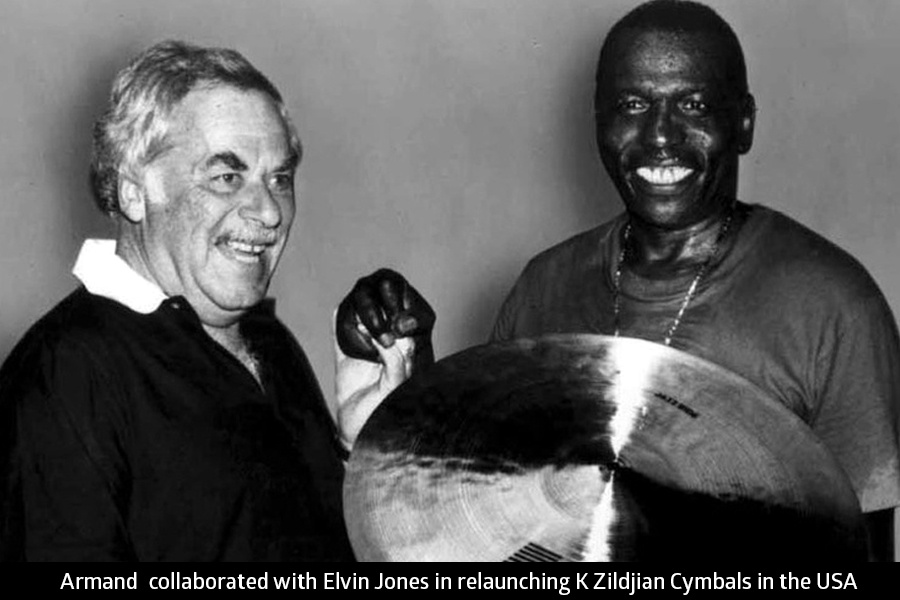

By 1950, Zildjian’s Quincy foundry was making about 70,000 cymbals per year. The one in Istanbul produced a fraction of that – between 5,000 and 6,000 “K” cymbals per year – until closing in 1978. With their dark, textured tones, the “K” series became particularly popular among next-generation jazz drummers in the ‘50s and ‘60s such as Art Blakey, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, Joe Morello, Max Roach, Alan Dawson, Shelly Manne and Tony Williams.

1960s: The Ringo effect, New Brunswick factory

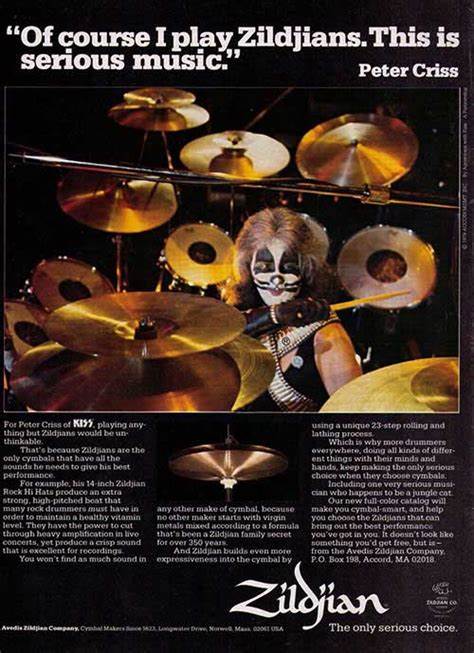

In the early ‘60s, by which time rock ‘n’ roll had replaced jazz in the hearts of most American teens, Zildjian faced the threat of significantly slower growth but the exact opposite happened starting in early 1964. Demand skyrocketed after Ringo Starr played Zildjians during The Beatles‘ debut appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February, resulting in backorders for 90,000 cymbals within days of the seminal broadcast. From then on, Zildjian become “the only serious choice” for generations of rock drummers.

By 1968, demand was so strong that the company opened a second plant, the Azco factory (managed by Robert), in Meductic, New Brunswick, Canada. Also in 1968, Zildjian regained all distribution and namesake rights from Gretsch, giving the company significantly more marketing control and financial stability.

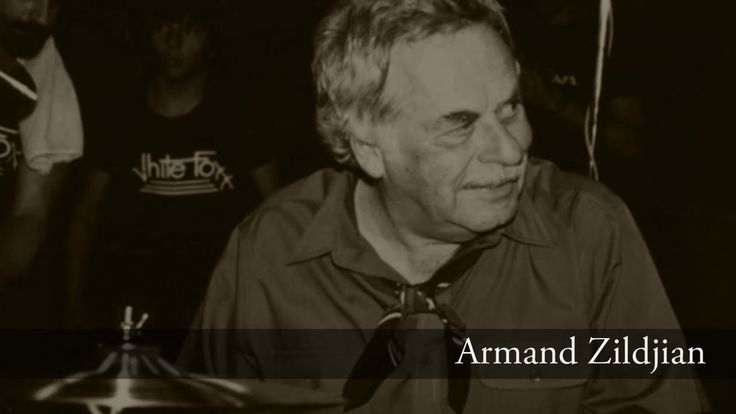

1970s, 1980s: Move to Norwell, Sabian, Drumstick factory

In 1973, the company’s 350th anniversary, Zildjian opened a new headquarters and foundry in Norwell, Massachusetts (about 25 miles from Boston), where it remains today. From 1975 to 1979, the Azco plant produced “K” cymbals but their manufacturing moved to Norwell in 1980. In 1977, 88-year old Avedis III appointed 56-year old Armand as Zildjian’s new president and in 1979, when Avedis III died, Armand became chairman of the board.

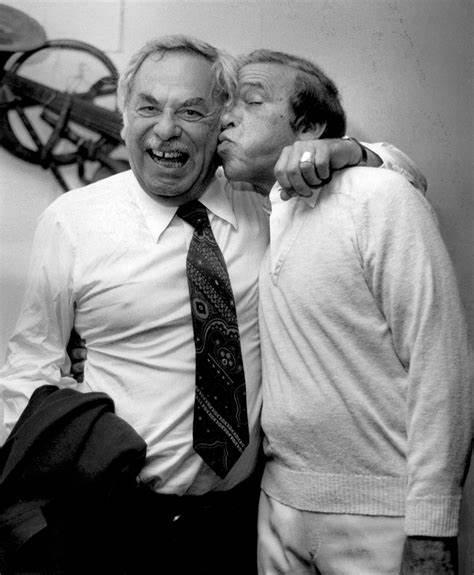

Though Armand was Avedis III’s oldest son and thus considered his rightful heir, Robert felt pushed aside and a nearly two-year court battle ensued. “It got to the point where they were taking away certain parts of my job,” he said in a 2004 interview. “I was the export man, the advertising man, the marketing man. I was quite a few things. All of a sudden, I was bereft of all that.” In the end, Armand maintained control of the Norwell facility and Robert inherited the one in New Brunswick, where he founded Sabian Cymbals in 1981. Armand passed away in 2002 at age 81; Robert died in 2013 at age 89.

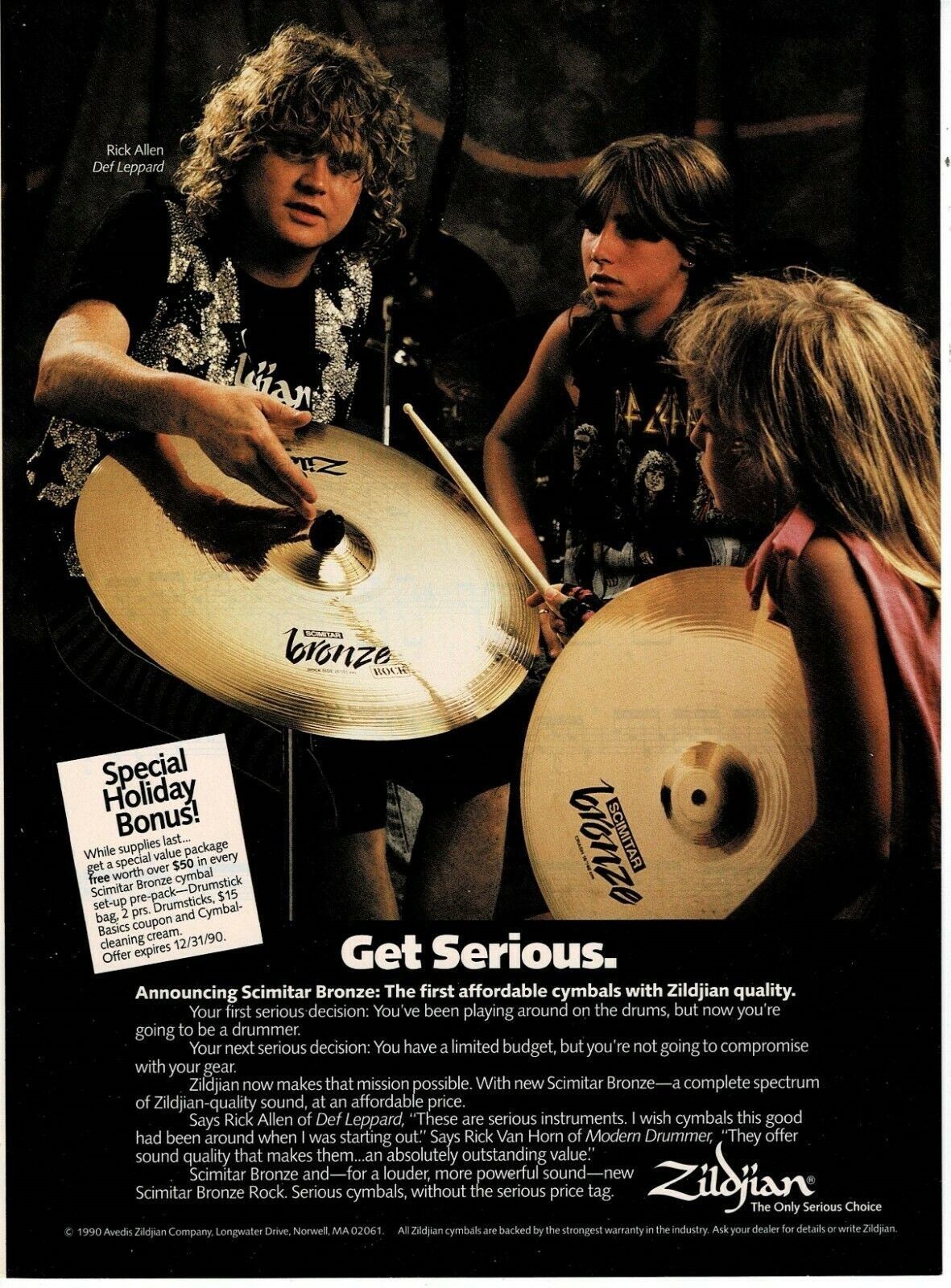

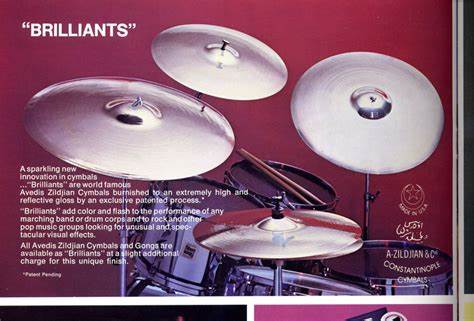

In the early 1980s, Zildjian made substantial investments in manufacturing technology, including computer-controlled hammering, double rolling mills and a rotary hearth. In 1986, Armand’s son Rab opened the first US Zildjian office outside of Massachusetts, an artist-liaison branch in Los Angeles: today, the company has offices in LA, London and Singapore. In 1988, Zildjian entered the drumstick market, opening a factory in hickory-rich Alabama.

1990s, 2000s, Vic Firth merger

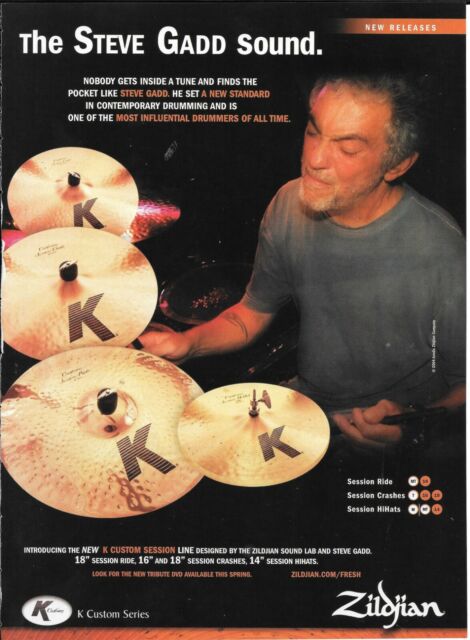

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Zildjian has remained the industry leader in terms of innovation, one example being the “A Custom” range it introduced in 1990, which some industry watchers said set a new standard for resonance and clarity. In 1995, the company designed a special room at the Norwell plant to assist orchestral players with their selections; among the visitors have been percussionists from the London Symphony Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In 1999, Armand appointed his daughter Craigie as CEO, making her the first woman in the role at Zildjian, and she held that position until 2017, when she became Zildjian’s executive chair and president. “My father always said that the name is bigger than any one person in the family,” she told The New York Times in 2018. “In other words, you have this little piece of 400 years. Don’t screw it up.” Today, there are four other Zildjians on the company’s board of directors: Armand’s daughter Debbie; Debbie’s daughters Cady and Emily; and Craigie’s daughter Samantha.

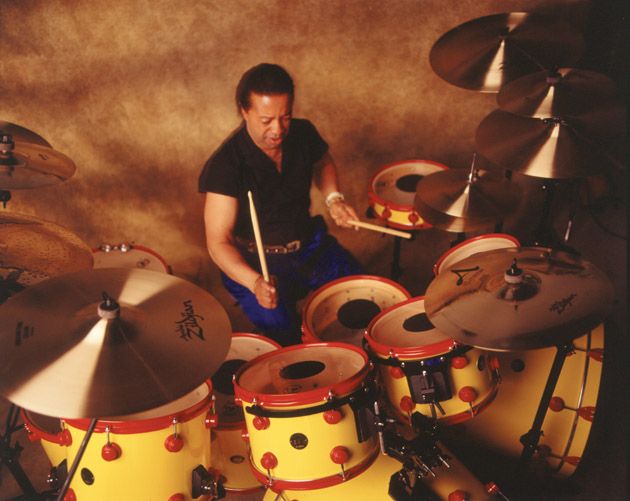

In 2010, Zildjian merged with Vic Firth Company, the world’s leading drumstick maker, and in 2018 the pair acquired Maine-based mallet manufacturer Mike Balter Mallets, making Zildjian/Vic Firth the largest manufacturer of sticks and mallets on the planet. In 2011, in an effort to enter the electronics-based DIY music sector, Zildjian unveiled its Gen16 Acoustic Electric series.

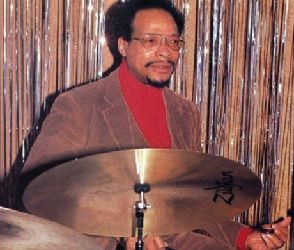

400th anniversary party, Zildjian Hall of Fame inductees

In September 2023, to celebrate its 400th anniversary, the company held a special event at Roadrunner in Boston (emceed by comedian-actor-drummer Fred Armisen) featuring live performances and the induction of eight drummers into the Zildjian Hall of Fame: Ringo Starr, Eddie Bayers, Dennis Chambers, Sheila E., Peter Erskine, Omar Hakim, Steve Smith and Terri Lyne Carrington. “It’s a special opportunity to be able to look back and be humbled by the storied history of my family’s company and all of the amazing, creative, and passionate people who have helped build something so meaningful,” Craigie said at the gala.

Comments on private ownership, spouses, drummers

Asked in a 2012 interview why the company has remained private instead of going public, Cragie Zildjian said that doing so has made long-term planning possible. “One of the advantages of a privately-held business, whether it’s a family business or not, is that you’re allowed to think long term,” she told Kim Gittleson of the BBC. “You don’t have to play to the stock market.”

Asked in the same interview if there were any upspoken rules between the five Zildjian women on the company’s board, Debbie noted the first in a serious tone and a second with a smile and a laugh. “Well, we’ve never let our spouses get involved in the business,” she said. “And we’ve always encouraged our daughters not to get involved with musicians – especially drummers!”

(by D.S. Monahan)