The Velvet Underground

While no protopunk band is more associated with New York City than The Velvet Underground and none of that genre is more associated with Boston than The Modern Lovers, the Velvets made The Boston Tea Party their musical bunker for over three years. And they did so more than two years before the Lovers – fronted by Velvets uberfan Jonathan Richman – were even formed.

And the Tea Party isn’t the only way in which Boston shaped the Velvets as they became one of rock’s most seminal bands: The city’s remarkable range of tremendously talented musicians had an indelible influence on the group’s lineup and sound, with three band members in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s rooted in the area.

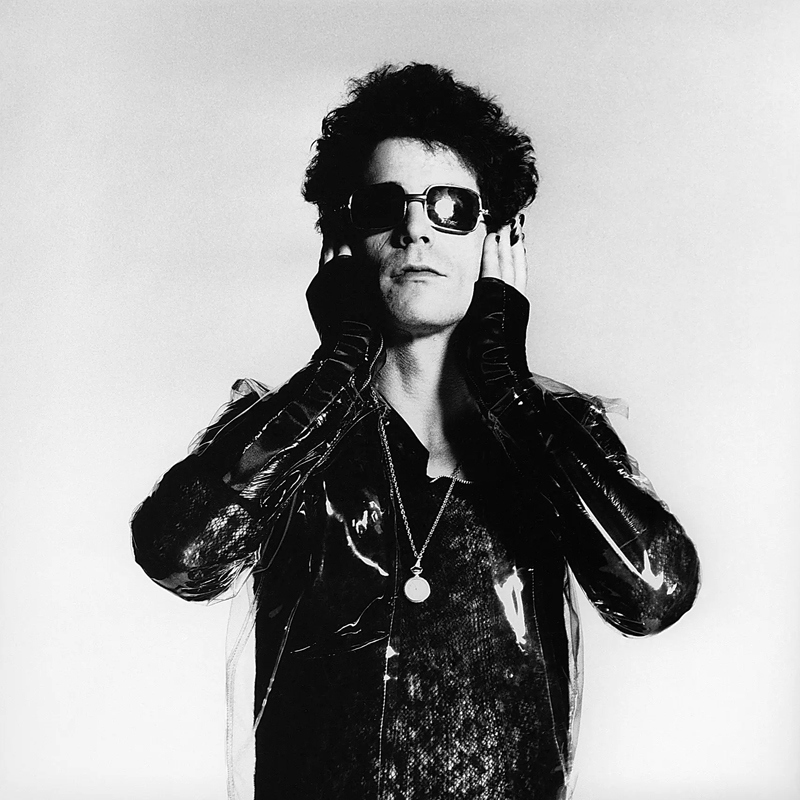

From May 1967 until mid-1970, the Velvets were one of the most frequent acts at the Tea Party, headlining dozens of shows. While their early gigs featured songs from their March 1967 debut album, later they worked out the harder-edged, distortion-drenched tracks featured on their second, 1967’s White Light/Heat, and their 1969 self-titled LP, allowing Boston-area fans to experience their revolutionary acoustical creations before anyone else as they watched the band evolve on stage. During a December 1968 Tea Party show, frontman Lou Reed championed the venue as “our favorite place to play in the whole country.”

FORMATION, DEBUT ALBUM

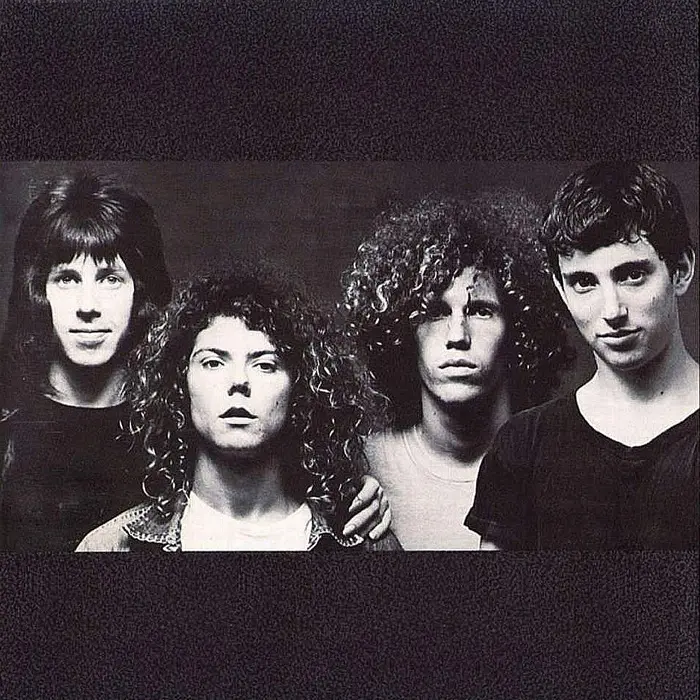

The group formed in 1964 under the patronage of artist Andy Warhol with the lineup of singer-songwriter-guitarist Reed, who was working at Pickwick Records as a songwriter and session musician; Welsh avant-garde multi-instrumentalist John Cale; guitarist Sterling Morrison; and drummer Angus MacLise, replaced in 1965 by Maureen “Moe” Tucker, a pioneer among female drummers.

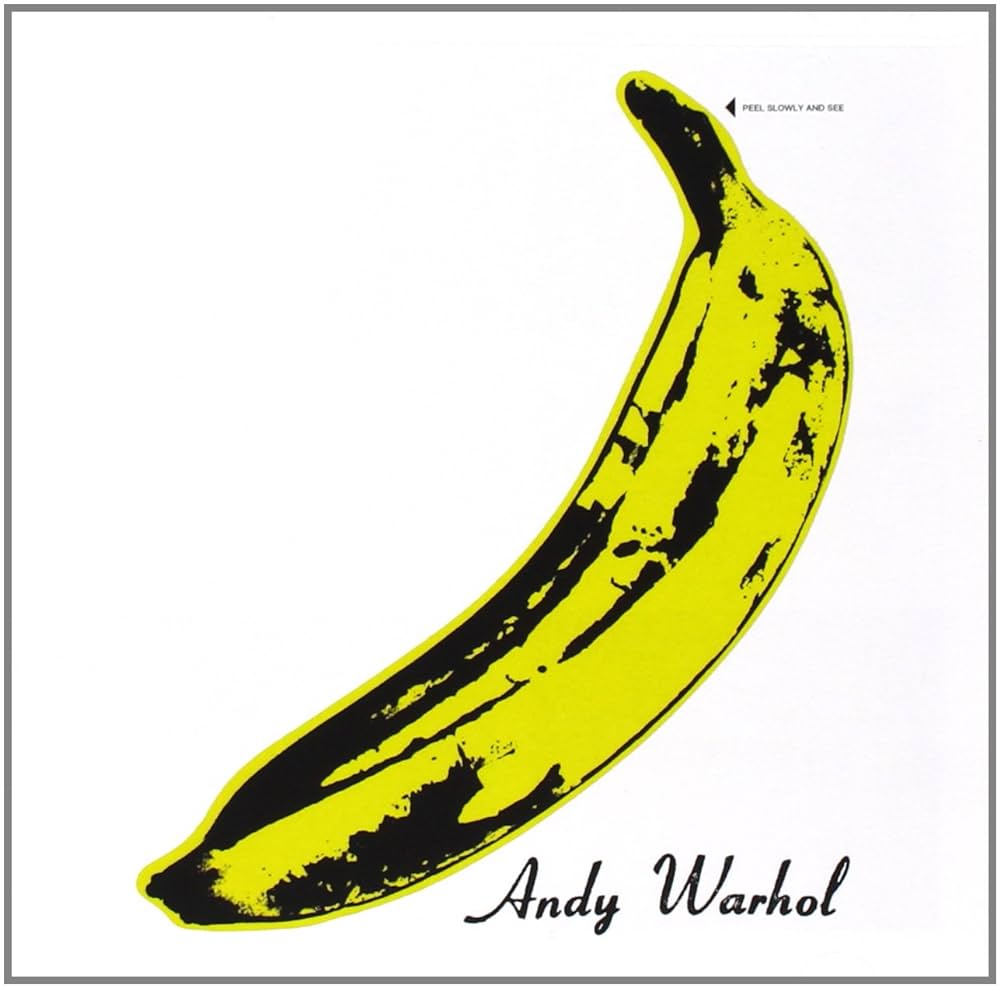

With Warhol as manager, the Velvets became the house band at his art collective, The Factory, and part of his multimedia show, The Exploding Plastic Inevitable. At Warhol’s insistence – and despite Reed’s outspoken objections – German model-vocalist Nico joined the group and sang on their debut LP, The Velvet Underground & Nico, issued on Verve Records in March 1967. The album was a commercial non-event since it received almost zero airplay and was banned by record stores for its inclusion of the song “Heroin” and what was considered sexually suggestive cover art; it sold a mere 30,000 copies during the five years following its release.

Critics hailed the LP as a major creative landmark, however, based on Reed’s spellbinding, streetwise lyrics, his sneering, half-sung delivery and the group’s skeletal, white-noise-rock compositions. It’s now considered an iconic part of rock’s canon, as is the cover featuring Warhol’s design of a life-sized banana which on the original pressings could be peeled away (revealing nothing more erotic than a banana beneath).

BOSTON TEA PARTY DEBUT, WOODROSE BALLROOM, MAX’S KANSAS CITY

The Velvets’ first appearance at the Tea Party was on May 26, 1967, 10 weeks after their debut hit the shelves and following the band’s decision to boycott New York City. The group’s move away from the Big Apple baffled critics and fans alike but was completely consistent with the band’s iconoclastic attitude and approach to recording, performing and music itself. Nico arrived to the show late, just in time for the final songs, and Reed refused to allow her on stage; she never performed with the Velvets again.

“You had a lot of people going to these ‘dance concerts’ we called them, pay three bucks, get in there and dance your butt off all night,” said Steve Nelson, manager of the Tea Party in 1967/8, in the documentary The Velvet Underground: One of the Most Unique and Underappreciated Bands of the 60s (Amplified, 2021). “And the Velvets were just a great dance band. You had a lot of local, blue-collar kids, students from Harvard and BU and an occasional professor. It rapidly became a kind of scene and for whatever reason, people in Boston just adopted them.”

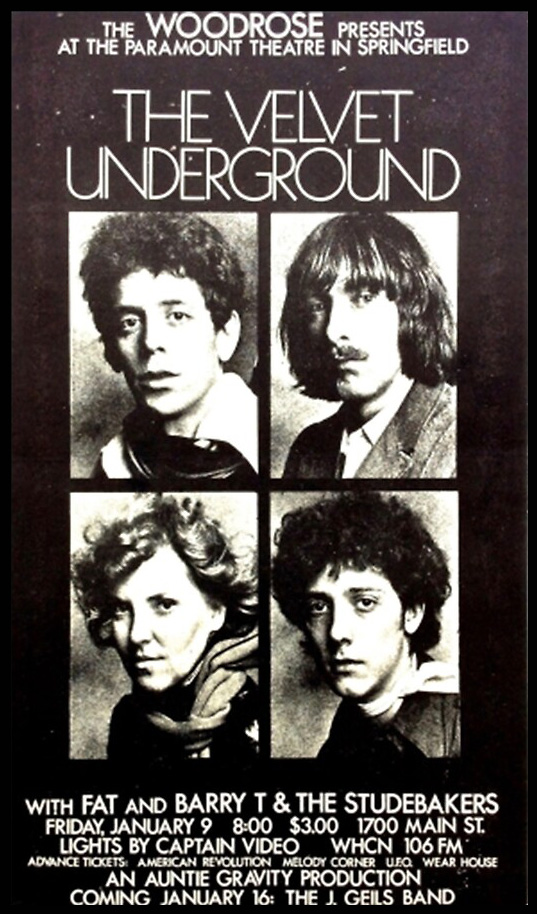

The Velvets also played The Woodrose Ballroom near Amherst multiple times, and they appeared there and the Tea Party combined more than at any other venue from 1967 until mid-1970, when they accepted an eight-week residency at Max’s Kansas City. Those shows turned out to be the last performances with Reed since he left the group abruptly that August, during the seventh week of the Max’s run. Warhol personally filmed one of the 1967 Tea Party shows on 16mm in color – the only known full-color footage of the original lineup playing live – and released it as The Velvet Underground in Boston, 1967.

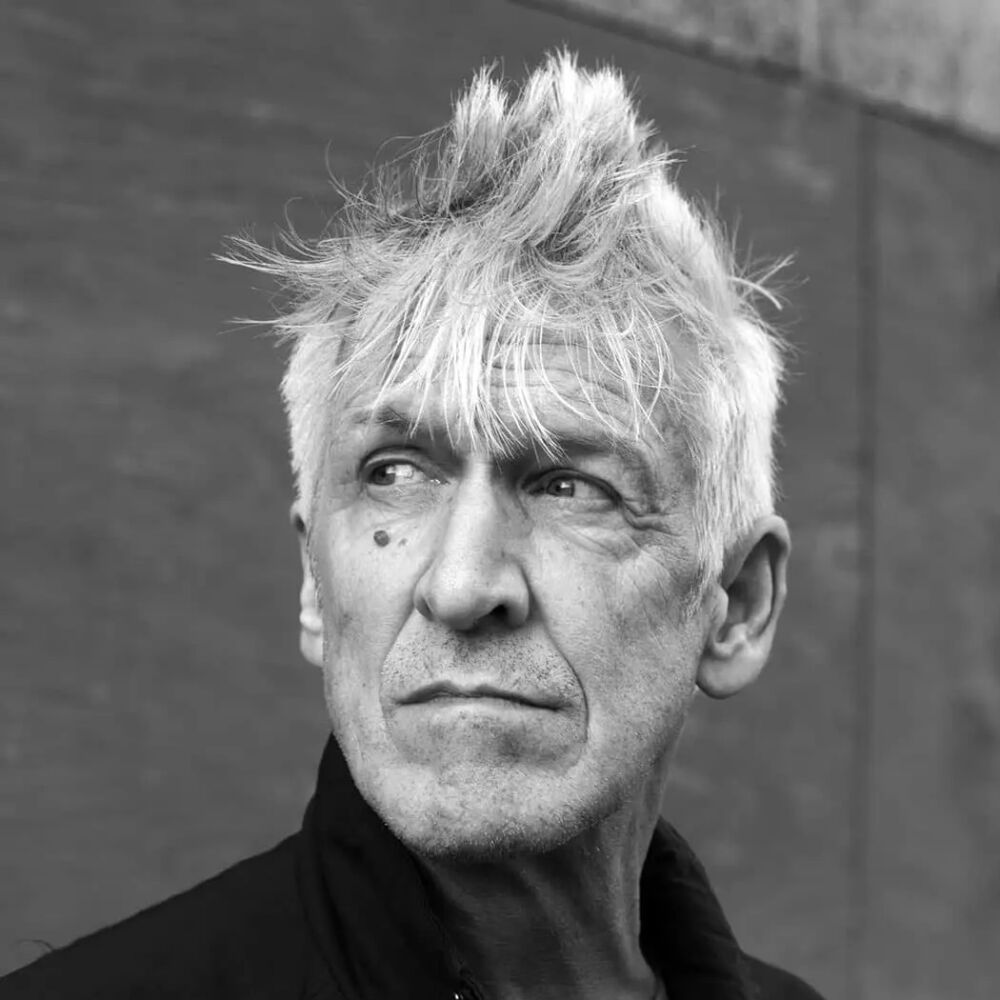

DOUG YULE

In terms of personnel, the first Boston-area musician to become a Velvet was keyboardist-bassist-vocalist Doug Yule, a Long Islander who studied at Boston University, played with Boston-based group The Grass Menagerie and joined in 1968 after the departure of Cale, whose mesmerizing viola and keyboards were core to the band’s original, oft-eerie, hypnotic sound.

Yule first met the Velvets at the Tea Party in mid-1968 and the band began staying at his River Street apartment, which Yule happened to be renting from the Velvets’ road manager. With Reed and Cale increasingly at odds over the band’s creative direction – Reed leaning toward a power-pop vibe and Cale insisting on anti-pop experimentation – in August Sterling Morrison invited Yule to audition for Reed and Tucker just in case Cale left the group, which he did two weeks later, playing his last show in September at the Tea Party.

THIRD ALBUM, LOADED, SQUEEZE

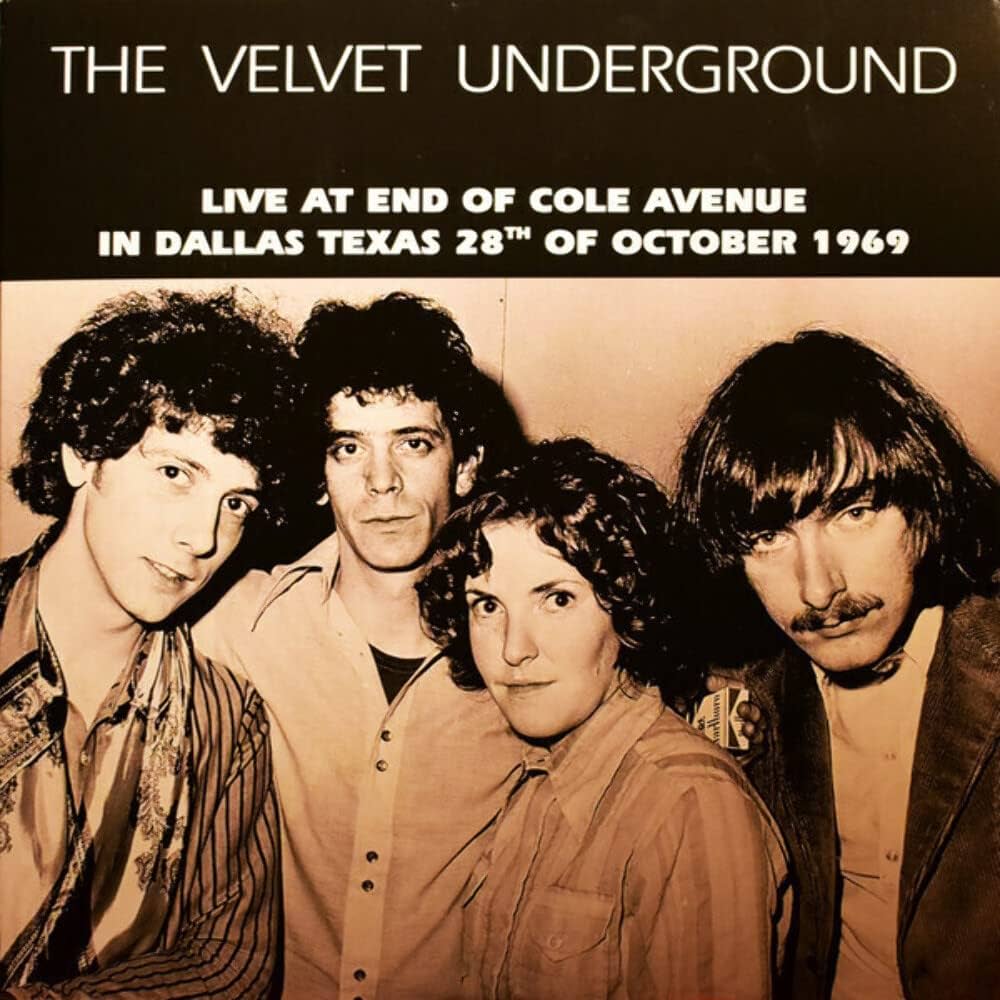

The sans-Cale Velvets recorded their eponymous third album in late 1968 with Yule singing lead on the Reed-penned song “Candy Says” (his first time being a vocalist in a studio), followed by 1970’s Loaded. Yule stayed with the band until 1973 – by which time no original members remained – and wrote, produced and played all instruments except saxophone and drums on the group’s final album, Squeeze, issued that year by Polydor. He also appears on the 1972 Cotillion release Live at Max’s and 1969: The Velvet Underground Live, recorded in San Francisco and Dallas and issued by Mercury in 1974.

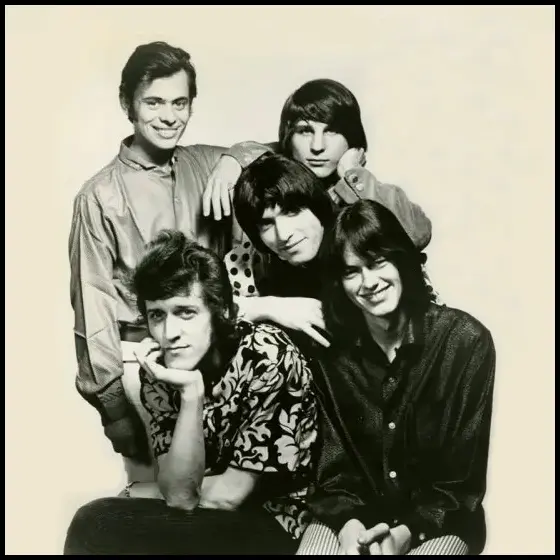

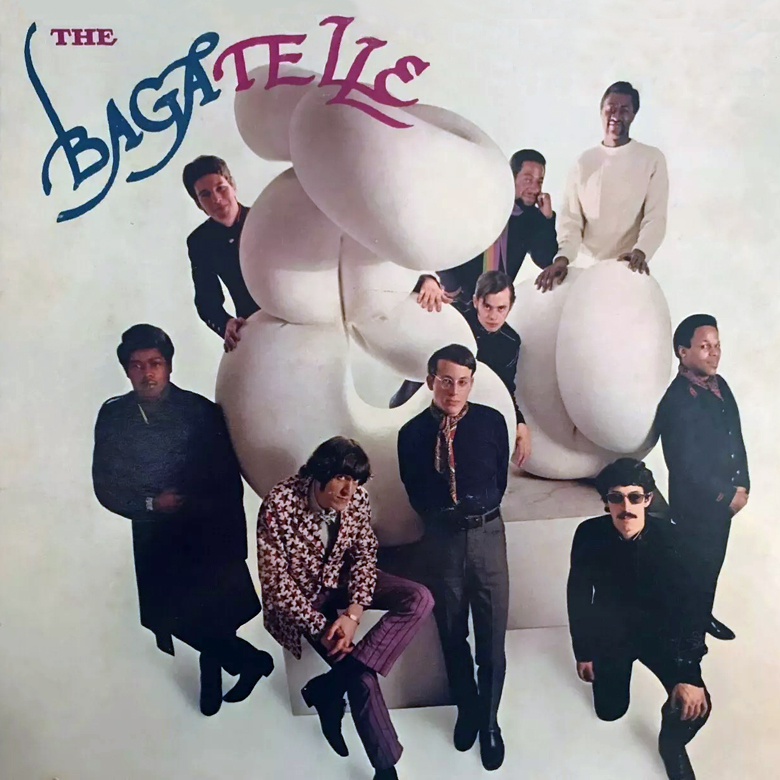

WALTER POWERS, WILLIE ALEXANDER, BOSTON TEA PARTY BOOTLEGS

The second new Velvet was Boston-born bassist-organist Walter Powers of The Lost, who joined the group in November 1970 when Yule switched from bass to guitar. The third was keyboardist-vocalist Willie Alexander, who’d played in The Lost, The Grass Menagerie and The Bagatelle, who came on board in 1971 when Morrison left the group. After that lineup toured North America, the UK and the Netherlands, Powers and Alexander left, the latter remaining a considerable presence on the punk scene.

Since the Velvets’ Tea Party period, multiple bootlegs of their shows there have surfaced in addition to one licensed LP, The Boston Tea Party January 10, 1969, issued in 2017 on the Spyglass label. With 12 tracks featuring the Velvets’ Reed-Morrison-Tucker-Yule incarnation, the album includes several classics such as “Heroin,” “Waiting For The Man,” “White Light White Heat” and “Sister Ray.”

LEGACY

Asked in the aforementioned documentary about the band’s legacy, former Tea Party manager Nelson said he thinks the Velvets were essentially a rock band trying to make the finest music they possibly could. “There was always a desire on the part of Lou, and I think Sterling and Maureen as well, to just be able to make good records, even to make a hit record,” he said. “And if you look at their early influences, you have Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, rockabilly, doo-wop, that kind of really basic roots rock and roll.”

“I know they had pressure from the label, from management, et cetera, et cetera,” he continued. “But I really think innately, in themselves, they just wanted to craft great rock ‘n’ roll records that people would listen to.”

(by D.S. Monahan)