Serge Chaloff

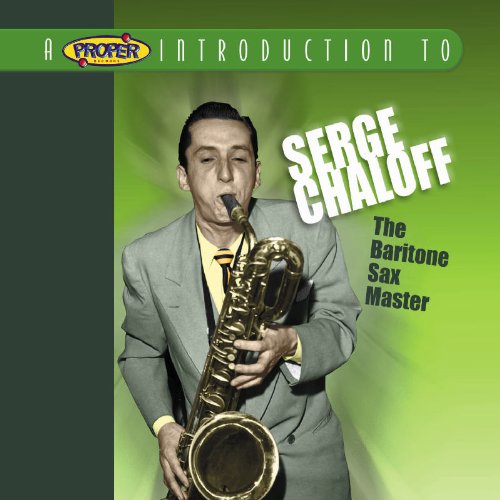

For those who know little or nothing about Serge Chaloff, here’s the big picture: He was “the most expressive and openly emotive baritone saxophonist jazz has ever witnessed,” according to critic Brian Davis in his liner notes for Chaloff’s classic LP Boston Blow-Up!

For those want to know more about the man credited as the first bebop baritonist – a simultaneously inspiring and heartbreaking tale of talent, triumph, addiction and disease – read on. Brace yourself, though, because this story is a doozy.

A child prodigy of particularly unique musical pedigree, Chaloff was born in Boston on November 24, 1923. His father, pianist/composer Julius Chaloff – also a child prodigy – enrolled at New England Conservatory at age 11, graduated with high honors at 17 and taught there for some 30 years before establishing his own music school. His mother, Margaret Stedman Chaloff (known professionally as Madame Chaloff), was the most sought-after piano teacher in the Boston area and, though she was classically trained, an eye-popping number of future jazz giants came to her Newton home for weekly or semi-weekly lessons through the 1940s,‘50s and ‘60s including Keith Jarrett, George Wein, Herbie Hancock, Fred Taylor, George Shearing, Ran Blake and Chick Corea. Legendary conductor/composer Leonard Bernstein was also among her students.

Given the perfect storm of his lineage and environment that drenched him before he could walk or talk – a 50/50 blend of nature and nurture as rare as there ever was – it’s no great surprise that Chaloff began learning two instruments at age six, piano (his mother being his first teacher) and clarinet (Manuel Valerio of the Boston Symphony Orchestra being his first teacher).

At age 12, Chaloff started teaching himself how to play the saxophone, inspired by Boston native Harry Carney of Duke Ellington’s orchestra. ‘Who could teach me? I couldn’t chase Carney around,” he said about his autodidactic approach, as quoted in Simon Says: The Sights and Sounds of the Swing Era, 1935-1955 (Arlington House, 1971). Chaloff also cited soprano saxophonist Jack Washington of Count Basie’s band as an early influence, saying that he and Carney showed him how to employ the full range of the instrument, the very skill that made Chaloff’s variety of tonality one of the most rarified and revered in jazz history.

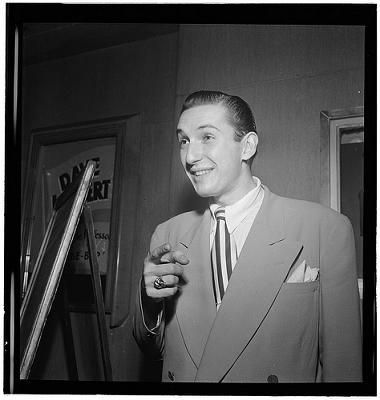

In 1937, 14-year-old Chaloff started sitting in on baritone sax at Izzy Ort’s Bar & Grill (later the Golden Nugget) on Essex Street in Boston and at age 16 he joined Tommy Reynolds and His Band of Tomorrow on tenor. In 1944, after stints with Dick Rogers, Shep Fields and Ina Ray Hutton’s groups – usually on baritone, which would be his sax of choice throughout his career – Chaloff joined Boyd Raeburn’s big band, playing alongside the now-iconic trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Al Cohn, the latter of whom became a lifelong friend.

In 1945, while part of Raeburn’s ensemble, Chaloff made his first recordings as bandleader, but that wasn’t the most important thing that happened in his life that year; seeing 25-year old bebop pioneer Charlie “Bird” Parker perform live was. Parker became Chaloff’s most enduring stylistic influence, driving him to play and compose on an emotional basis rather than on a strictly technical one, he often said, and he began sitting in with Parker at clubs all over New York City.

After leaving Raeburn’s band in late 1945, Chaloff moved between four bands in 1946 – Sonny Berman’s Big Eight, Bill Harris’ Big Eight, The Ralph Burns Quintet and Red Rodney’s Be-Boppers – before forming his own group, The Serge Chaloff Sextet, and recording four tracks for Savoy Records, three of which he wrote and arranged.

In 1947, Chaloff joined Woody Herman’s band Second Herd, an offshoot of which, The Four Brothers Band – named after Herman’s four saxophonists, Chaloff, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims and Herbie Stewart (and later Al Cohn) – started performing and recording on their own. He was featured as a soloist on many of Herman’s records, including the track “Man, Don’t Be Ridiculous,” where he demonstrated a technical facility that was “quite without precedent on the instrument,” wrote critic Joop Visser in the liner notes to Serge Chaloff: Boss Baritone (Proper Records, 2011).

Also in 1947, 24-year-old Chaloff was in the throes of heroin addiction – as was Charlie Parker – and was the Woody Herman band’s “chief druggist as well as its number one junkie,” wrote critic/lyricist Gene Lees in Jazzletter in 1984. Whitney Balliett, jazz critic for The New Yorker, wrote that Chaloff had “a satanic reputation as a drug addict whose proselytizing ways with drugs reportedly damaged more people than just himself” and a number of musicians blamed him for the fatal 1947 drug overdose of the Woody Herman band’s 21-year-old trumpeter Sonny Berman, a New Haven, Connecticut, native.

In late 1949, exasperated by Chaloff’s (and several other of his band members’) daily heroin use – which had begun to significantly affect their performances, and not in a good way – Herman broke up Second Herd to front a smaller, Chicago-based combo. “You can’t imagine how good it feels to look at my present group and find them all awake,” he told DownBeat in 1950. “To play a set and not have someone conk out in the middle of a chorus.”

For the first months of 1950, Chaloff played in Count Basie’s All Star Octet, formed after Basie, in tandem with Herman, broke up his big band. After recording several tracks with them, he returned to Boston and gigged with a number of small combos at clubs including the Hi-Hat in Boston and the Red Fox Café in Cambridge. In 1994, Uptown Records issued Boston 1950, a 17-track CD of material recorded at the Hi-Hat and Providence’s Celebrity Club where Chaloff led a quintet. Many critics have said that his playing with smaller groups during this period propelled his soloing to a richer, more soul-stirring level of emotiveness.

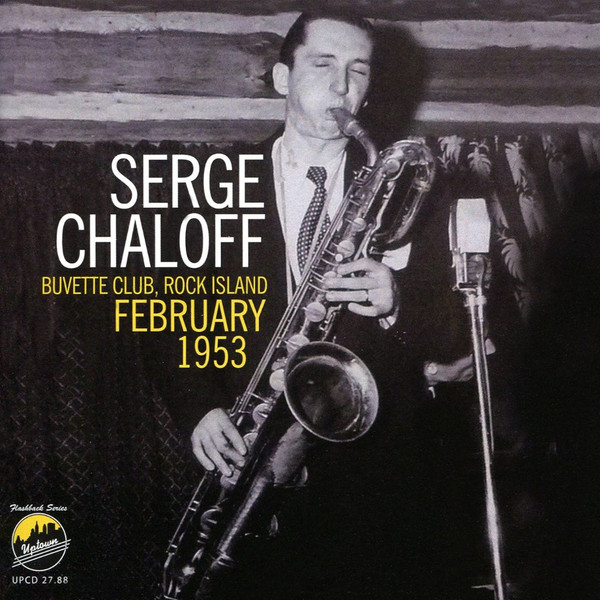

Strung out and broke, using whatever money he earned to support his habit, after continuing to play small-combo club gigs through 1951, Chaloff stopped playing altogether from early 1952 until the end of 1953, when Boston deejay Bob “The Robin” Martin offered to become his manager. With his help, Chaloff landed spots at Boston clubs Jazzorama and Storyville – the latter owned by George Wein, who founded the Newport Jazz Festival in 1954 – with his most frequent musical partners, all Massachusetts natives, being Boots Mussulli of Milford (alto), Charlie Mariano of Boston (alto), Dick Twardzik of Danvers (piano) and Herb Pomeroy of Gloucester (trumpet).

Despite his immense talent and consistent accolades and awards, Chaloff’s heroin dependency made most club owners reluctant to book him, as he was known for arriving to gigs high, drunk, both or – notoriously – not showing up at all. “He didn’t work a lot,” Martin wrote in the liner notes to Boston 1950, “because the word [of his heroin habit] was out. When you got him a gig in a club or a hotel, he would usually mess it up. But when he did show…it was, ‘Stand back, baby!’”

In 1954, Chaloff recorded two LP’s for the Storyville label, the first being Serge and Boots, a joint album with Mussulli featuring five standards, all of which Chaloff arranged, and one Chaloff original, “Zdot,” the ending of which was written by his mother. The second, The Fable of Mabel, was recorded with a nine-piece band that included Mariano, Twardzik and Pomeroy.

In mid-October 1954, one month after finishing sessions for The Fable of Mable, Chaloff voluntarily entered Bridgewater State Hospital’s drug rehabilitation program and was hospitalized there for almost four months before his discharge in February 1955. He came out heroin-free – for the first time in a decade – and two months later the clean-and-sober future legend’s career was swingin’ to beat the band like never before.

In March 1955, he recorded his comeback album, Boston Blow-Up!, with The Serge Chaloff Sextet (Mussulli, Pomeroy, pianist and future Berklee professor Ray Santisi and drummer Jimmy Zitano), which Capitol released in April. DownBeat critic Jack Tracy gave the LP five stars, calling Chaloff’s playing “a thing of beauty” and the album “the best display of his talents ever to be put on wax…the long-awaited coalescence of a great talent.” Later in 1955, Chaloff helped establish The Jazz Workshop in Boston with Mariano, Pomeroy, Twardzik, Santisi and tenor saxophonist Varty Haroutunian.

Rhapsodic reviews for Boston Blow-Up! resulted in a fully booked schedule over the next two months, culminating with an appearance at the Boston Arts Festival in June 1955. In early 1956, Chaloff played his way across the US to Los Angeles where he recorded his second album for Capitol, Blue Serge, featuring drummer Philly Joe Jones, pianist Sonny Clark and bassist Leroy Vinnegar. Reviews were unanimously effusive with the word “masterpiece” a recurring theme, and 32-year-old Chaloff – who just five years before had stopped playing for nearly two years – was at the peak of his abilities and his acclaim.

Then tragedy struck. In May 1956, while golfing in Los Angeles the day before starting a four-night stand at Hollywood’s Starlite Club, he suffered sudden and severe abdominal and back pains that paralyzed both his legs, leading him to fly back to Boston where an exploratory operation at Massachusetts General Hospital revealed that he had advanced spine cancer. Surgery removed most of the tumors on his spine, but x-rays indicated that the disease had metastasized to one of Chaloff’s lungs.

Despite the grave situation and the grueling operation, he continued making live appearances. In June 1956, a wheelchair-bound Chaloff played on a recording of Charlie Parker’s “Billie’s Bounce” in a New York City studio for the Verve Records release Metronome All-Stars 1956 along with Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, Billy Taylor and Zoot Sims. In February 1957, Chaloff made his last recording, The Four Brothers…Together Again!, with Al Cohn, Herbie Stewart and Zoot Simms for the RCA Victor subsidiary Vik Records. “The blowing is the thing, and the fellows… give fine accountings of themselves,” said the Billboard magazine review.

In May 1957, Chaloff made his final live appearance, at The Stable in Boston’s Back Bay, drinking beer and smoking marijuana before and after the show, saying that it eased his near-constant pain. On July 15, 1957, he was admitted again to Massachusetts General Hospital, where he died the next day at age 33 and was buried the following week in the Forrest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain.

According to his older brother Richard (1921-2005), Chaloff had his sax with him in the hospital and nurses wheeled him into a vacant operating theatre the day before his death so he could practice. “That was his last gig, his last public performance. Nurses, doctors and even patients were standing outside and listening,” he said at the time. “He fought to the end.”

(by D.S. Monahan)