Hairs Apparent

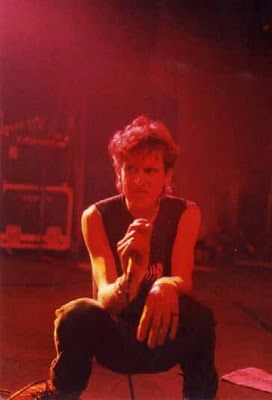

Ted Myers is a songwriter, musician and producer living in Los Angeles. He was a founding member, with Willie “Loco” Alexander and Walter Powers, of The Lost, one of Boston’s pioneering rock bands c. 1964-1967.

I think it was the Sonny & Cher gig that put us over the top. For a long time there, back in 1965, we were highly dissatisfied with the P.A. systems we encountered at almost every gig. By “we” I mean The Lost, my first rock ‘n’ roll band, a raggle-taggle bunch of white punks on dope, stumbling toward ecstasy at the dawn of the psychedelic era. So here we were, opening in Troy, NY for Sonny & Cher. They were huge, man! Second on the bill was Len “1-2-3” Barry. “1-2-3” was a number 2 pop smash in 1965. So why, then, why, I ask you, was it that when we took the stage (the very first act of the night) and started to sing absolutely nothing came out of the stinkin’ P.A. system!!!? It took a few moments to sink in–that the words to the song we were singing were going completely unheard–then, thinking fast, I remember calling out to my lead guitarist: “Instrumental!” At first he looked at me, uncomprehending. “Instrumental!” I yelled again, and we shifted gears–quite seamlessly if I may say so–to the Stones’ “2120 South Michigan Avenue,” one of our staples. We vamped on this a good long time. I knew the guys in the sound booth were doing their damnedest to fix the problem, so I wanted to buy time for them as well. I was actually thinking of their well being! We went on for what must have been ten minutes, then ended the song. Scattered applause. I approached the mic, said “Hello, can you hear me?” Nothing.

I guess it was this experience that got us to thinking we should bring in our own sound system. In 1965 there was no such thing as onstage monitors. There were no hi-tech multi-track mixing boards. There were no sound roadies accompanying every act, busting the balls of the promoter if the sound wasn’t just right during the sound check. There weren’t even sound checks! You just walked onstage and played. The people doing the sound at these places didn’t know or care about your music — they didn’t know you from P.J. Proby and could care less!

I don’t remember who suggested the Hanley brothers. They were developing a rep around Boston for being the cutting edge of live sound. Four years later they would do the sound at Woodstock, which would put them on the map. The Lost would be long gone by then. But in 1965, we were, briefly, the flavor of the year. We were the new vunderkinds on Capitol Records, the “hairs apparent” to the Beach Boys and The Beatles. So when we were booked to open for the Supremes at Brandeis University, we called the Hanley brothers. We would not be unheard again! The venue at Brandeis turned out to be this huge indoor gymnasium.

The Hanleys brought in a pair of speaker stacks that looked like Godzilla’s port-a-potties. They mic’d every amp, every drum. There were monitor speakers at our feet, a luxury, as I said, virtually unheard of in 1965. The Supremes and their backup band, the King Curtis Orchestra, would be relegated to the house sound system. We were so ready.

We took the stage at eight o’clock sharp, ready to rock the socks off those collegiate snots. There had been some talk backstage, and we didn’t like it one bit. It seems the Student Activities Committee had settled for us as second best. They had really wanted The Blues Project (some of whom apparently were Brandeis alumni), not us. So we had a sort of chip on our shoulder from the start. The moment we walked onstage, we could sense a certain air of hostility.

Our first number was an original that started off with a big, ringing guitar chord–sort of a “brang!” I remember hitting that chord and seeing the first five rows go down. The sound was so big, so loud, so unexpected that I guess they just dove under their seats. When we started to sing another few rows went under. By halfway through the song they were standing up and booing with their fingers in their ears. It began to dawn on us that we were killing our audience with volume–the sissies. As the first song ended there was a cacophony of boos and cries of “Get off!” We were insulted, but doggedly pressed on. We tried to turn our amps down, but with the close mics that did little good. I searched the horizon frantically, looking for one of the Hanleys but, alas, they were nowhere to be seen. After the second song the boos were even louder–the deafening din of rejection. We couldn’t face it. At last we walked off the stage, flipping them off as we fled. If these fools weren’t ready for state-of-the-art technology, someone else would be, sooner or later.

Unfortunately, later turned out to be sooner for the Lost. We lasted only about a year on Capitol, which never picked up any of the six options we had left on our contract. We did make one or two breakthroughs during that lone quarter hour of my rock ‘n’ roll fame: we were the first (that I know of) to use psychedelic lighting as part of our show, among the very early users of feedback and other sound effects generated from a weird array of honkers, tooters, sirens and other gizmos, and, as you know, were among the first to pioneer the live sound technology routinely used today. Think of it this way: a few eardrums were sacrificed so that many could rock.