The Hi-Hat

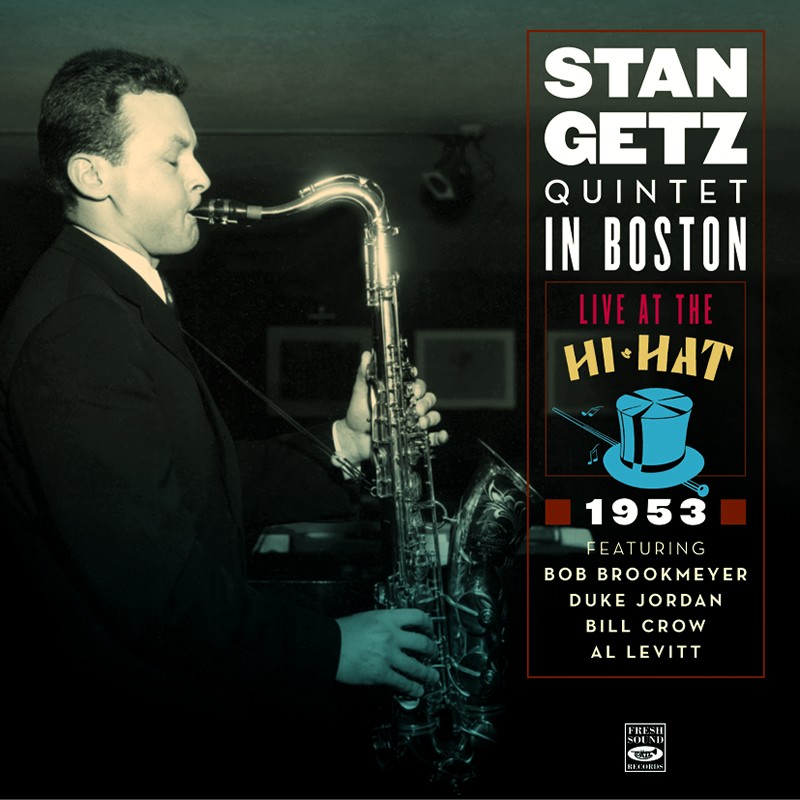

Imagine, if you can, a time when a world-class jazzman would come to Boston on his own, hook up with local sidemen and produce a live album at a nightclub that still sounds fresh and lively three score and ten years later. That time was 1955 and the place was The Hi-Hat, a club named after the drum kit accessory comprised of two cymbals manipulated by a foot pedal that was perfected, if not invented, in Worcester, Massachusetts by musical-instrument manufacturer Barney Walberg.

The headliner in question was Miles Davis and the sidemen were Jay Migliori on tenor, Al Wolcott on piano, Jimmy Woode on bass and Jimmy “J.Z.” Zitano on drums. The album is Miles Davis: Live at The Hi-Hat – Boston (Jazz Door, 1991). That such an event could have occurred in Boston, handmaiden to New York City’s jazz scene, is remarkable on its own. That The Hi-Hat survived from 1937 until it burned down in 1959 makes its longevity that much more remarkable.

OPENING, COMPETITION, INTEGRATION

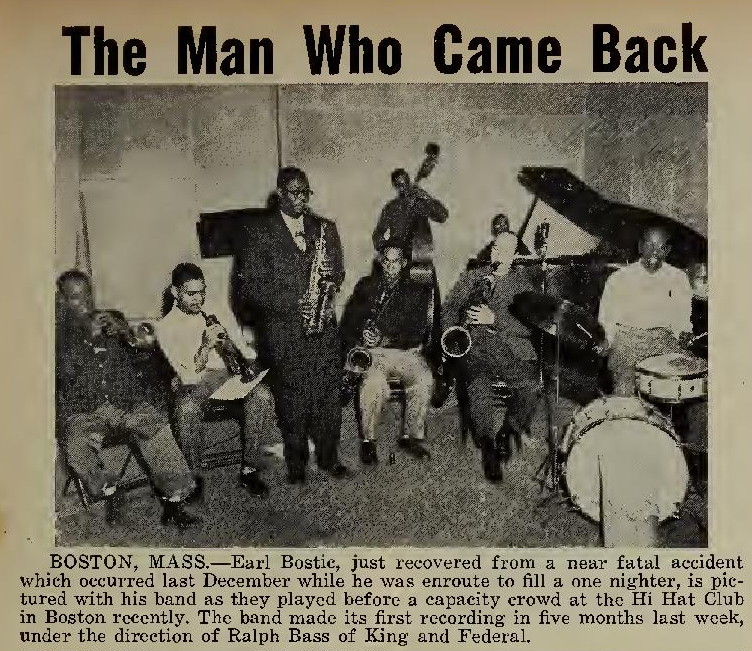

The Hi-Hat opened in 1937 at the corner of Massachusetts and Columbus avenues in Boston’s South End, the neighborhood that Brahmin poet Robert Lowell called the “razor’s edge of Boston’s negro culture”; Lowell said he could hear Black music from his open windows in the Back Bay. The club closed for a time in 1955 due to another fire; while this author has no reason to suspect that either blaze was set intentionally, arson was a common ruse for club owners who wanted to cut their losses by collecting on their fire insurance policies. Considerate operators would “tell the musicians to take their instruments home” the night the deed was to be done, according to David Bradbury, a Duke Ellington biographer.

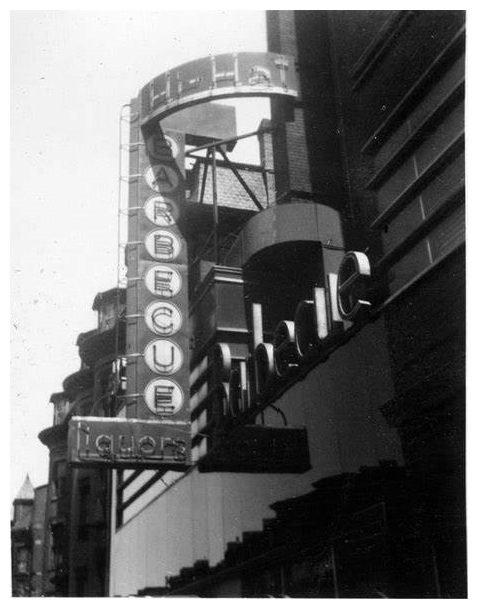

Like its New York City counterpart The Cotton Club, The Hi-Hat originally served only white patrons. Bands that played there in its segregated days offered low-volume tafelmusik (German for “table music”) to be listened to while dining and not danced to. Patrons were greeted by a doorman in a tuxedo and strolled into the club under a scarlet awning. Advertisements promoted the venue as “America’s Smartest Barbeque,” a claim that anyone who has traveled west and south of New England will strongly doubt, but not atypical of self-centered Bostonians who considered their burg the Hub of the Solar System. Still, The Hi-Hat’s bill of fare was exotic for those who had been raised on baked beans and broiled scrod.

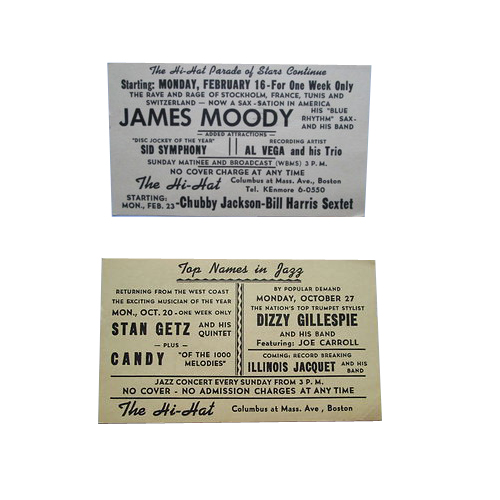

The club evolved due to competition; in the mid-’40s, neighboring venues such as The Savoy, Eddie Levine’s, The 4-11 Lounge and Wally’s Paradise began to attract crowds with jazz, particularly of the “Dixieland” variety, and the tonier clubs in Bay Village may have drawn off white patrons. Deciding to swim with the current instead of against it, The Hi-Hat dropped its segregated admissions policy and began to book jazz in the late 1940s. Owner “Julie Rhodes” (real name: Julian Rosenberg) first hired a white trio consisting of pianist Nat Pierce, drummer Joe MacDonald and alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano. Pierce lived nearby, at 458 Massachusetts Avenue. “I had a little upright piano in my humble apartment near The Hi-Hat,” he recalled in later years, and big names like Count Basie would drop by after their sets.

SABBY LEWIS, CHARLIE PARKER, BILLIE HOLIDAY, THELONIOUS MONK

The change in format was received favorably and Rhodes decided to expand the entertainment from a trio to a larger ensemble led by Black bandleader Sebastian “Sabby” Lewis, which typically had seven pieces and eight with a vocalist. Lewis’s brand of music wasn’t as popular as the Dixieland that was attracting crowds to other clubs, but it retained its appeal to fans of swing dance music. Lewis wasn’t a native Bostonian, but he had built a large local following so the choice proved to be profitable one.

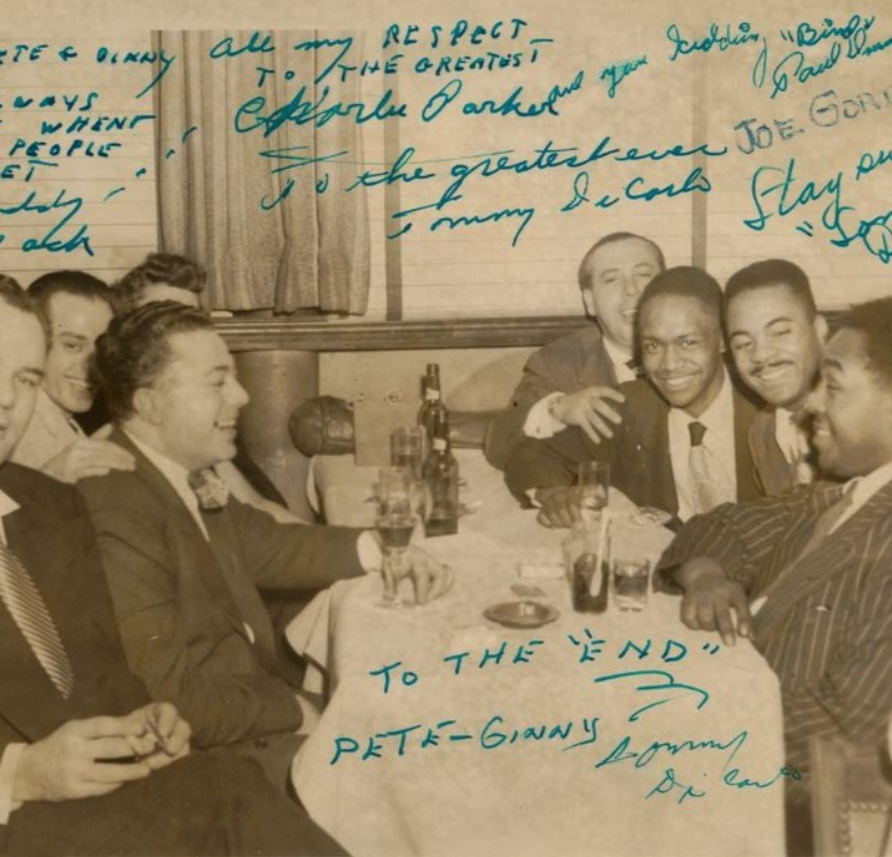

Rhodes wasn’t equipped to recognize musical talent, so at Lewis’s suggestion he hired Ray Barron, a musician and bandleader who hosted a weekly jazz show, to book bands for him. As recounted by Al Vega, a regular pianist at the club in the ‘50s, “Ray would tell Julie who Charlie Parker was, that he should hire Charlie Parker. So he’d do that, but he still couldn’t evaluate quality.” As a result, The Hi-Hat booked some of the biggest names in the business, including Erroll Garner, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and Parker. Holiday and Parker began to perform frequently at the club when they lost their New York cabaret licenses due to drug problems and couldn’t perform there.

The other power behind The Hi-Hat throne was Dave Coleman, described by Richard Vacca in The Boston Jazz Chronicles as “a college-trained chemist and frustrated musician,” who “knew the club business,” and had “been bit by the modern jazz bug.” Coleman’s influence accounted for the 1955 Davis date and a 1950 appearance by Thelonius Monk, his first in Boston as a headliner.

Monk’s music mystified club owner Rhodes, according to Hi Diggs, a pianist in The Hi-Hat house band. “Monk sat down at the piano and played to a small group of people,” he said. “Julie was not to be considered a square, but when Monk started playing some of his own sounds, he was completely baffled. Julie turned to me and asked, ‘Is he really good?’ I put on my hippest look and said, ‘He’s a genius,’ which of course he was, and for the sake of this gig, I was convincing.”

And so Boston was brought, hesitantly if not exactly kicking and screaming, into the bebop era.

(by Con Chapman)

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press, 2019), Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and Sax Expat: Don Byas (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).