I Was a Teenage Orpheum Usher

I didn’t have much of a musical childhood. My parents were big Neil Diamond fans but I couldn’t talk about him with friends, since I was in middle school more than 15 years before singing “Sweet Caroline” at full voice became a tradition at Red Sox games in the late ’90s. In late 1981, when some of my classmates passed around a cassette of The J. Geils Band’s Freeze Frame album, with its creepy potato-head on the cover, I was repelled.

But in high school my buddy Ian pretty much saved me, since his mom knew the head usher at the Orpheum Theatre and got a bunch of us jobs in 1985. Over the next few years, I saw well over a 100 shows there, from Adam Ant and Warren Zevon to the Boston Gay Men’s Choir and the Christian rock band Petra.

It was a big jump for a sheltered, nerdy kid like me. I had to take a bus to the barn of the old Forest Hills Station, then ride the elevated Orange Line into town, then make the return trip, sometimes after midnight. But it gave me something to talk about with my grandfather: He’d worked at the Orpheum in the 1930s, moving one copy of a film, one reel at a time, among three different theaters, speeding through Boston streets so fast that sometimes when he turned, the wheels came off the ground like they do in cartoons.

My first impression of the theater as a 15-year old was that it was a dump. The lobby was dim, the scratched mirrors smoky and the plaster curlicues on the dingy walls that had once been painted gold were now chipped, if not broken. The ancient carpet was worn smooth by untold thousands of feet, with spots of solidified gum like patched potholes.

I worked the balcony, where it was even darker and the walls were scarred by cigarettes and graffiti. Smoke and hairspray lingered in the air. I got my first look at the actual theatre through one of the tunnels to the seating area. Finally, I recognized the once-grand past. The ceiling wore faded murals, the internal dome partially covered by modern sound baffles. The mezzanine peered right over the stage. Everything was covered in dust, with more of that tarnished gold paint. I remember wishing that I had a million dollars so that I could restore it.

When we first joined the staff, a veteran usher gave us a quick lesson on how the seats were laid out: evens to the right, odds to the left and, though each row had a letter designation, there was no row “I” because some people confused it with the number “1” and thought it meant they had a front-row when seeing it on their ticket. I had a big D-cell flashlight, but I was told to bring a palm-sized one next time, along with a white t-shirt, which was the closest thing we had to a uniform.

The full-time ushers came straight out of central casting. One wore dark round glasses, had many piercings and kept his hair in a long pony tail. Ignorant to the illegal drug world in every way, my friends and I wondered if he was on LSD. There were stoners and professional-looking adults who might have been symphonic musicians and I recall a rather profane 40-ish woman with her own band. One usher who was closer to my age was a Madonna fan with neon-colored outfits and plastic bangles up her arm. She let me wear her ear cuff one night – I secretly wanted (but feared) to get my ear pierced – and to this day I have no idea how my dad found about it.

On every shift, we’d get word the doors were “opening in five,” and for about 45 minutes after that we were working nonstop, reading tickets, pointing to other sections, leading people up the steeply-raked rows. Once the show started, we stood inside the tunnel, looking past each other to see the performers. After about an hour of the artist/band hitting the stage, we were allowed to leave the theatre or to find an empty, uncomfortably narrow seat the very top of the balcony section.

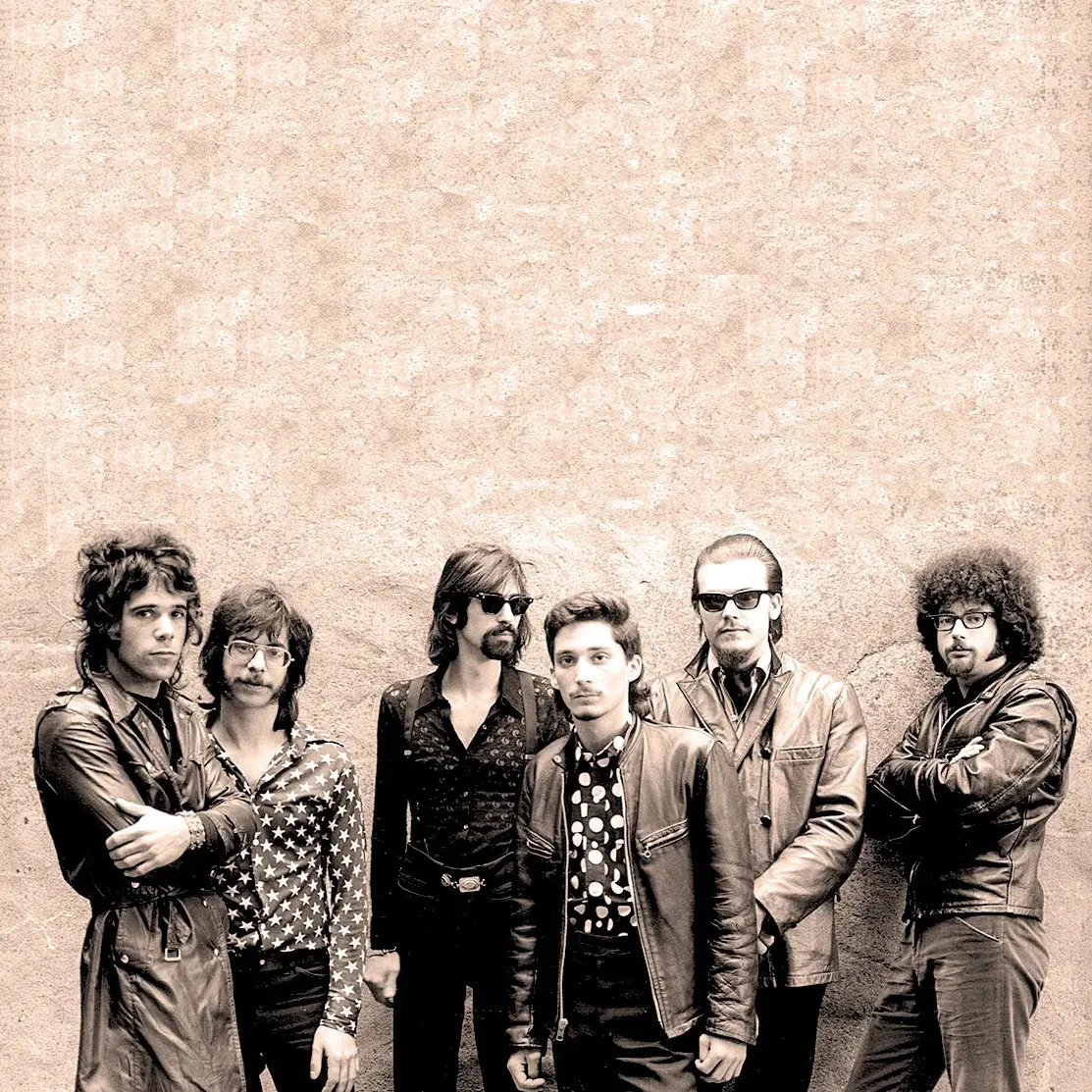

As for Orpheum crowds, they were very different depending on the act. Heavy metal bands like Megadeath and Anthrax attracted aggressive big-haired men and women. Classic ’80s pop bands like The Thomson Twins and Huey Lewis & The News brought in clean-cut kids around my age, and I felt cool because I got to see the shows for free. I remember the night a-ha played very well since the place was full of screaming tweens. In one group of four, each had a small sign – one with “We,” a second with “Love,” a third with “a” and a fourth with “ha” – so together it looked like one giant message to the band. I remember how devastated they were when I told them that their seats (numbered 10, 11, 12, 13) were on opposite sides of the theater (because of the even/odd system) and so the sign would be split up, too. When The Jerry Garcia Band played, the fans were incredibly generous, offering us free drugs while they danced in the aisles and we tried to get them to their seats. At some shows by postpunk groups like X, Siouxsie & the Banshees and PiL, the crowd’s stamping shook the roughly 80-year-old balcony to the point we thought it might collapse.

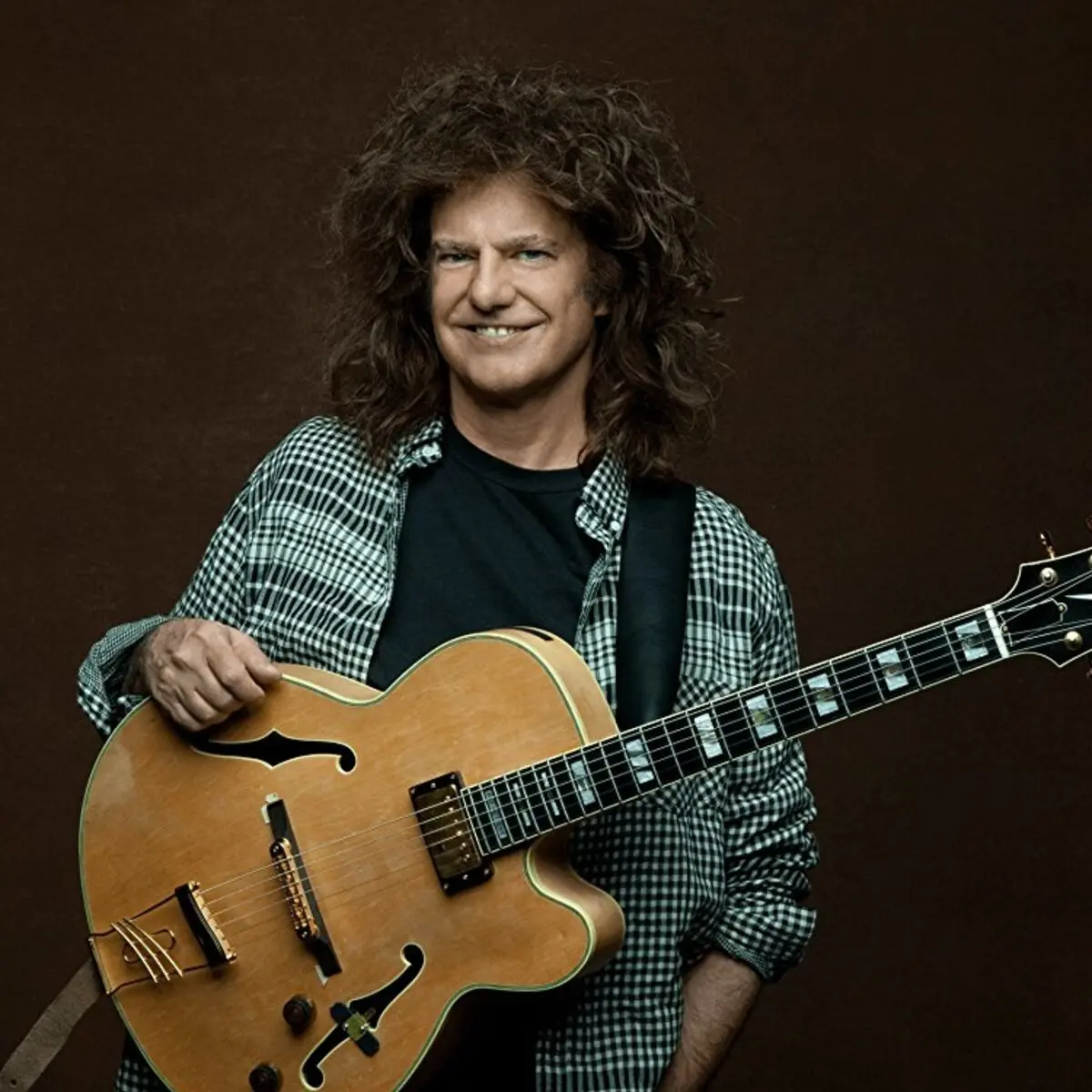

For a kid with no musical background, I got quite an education. I’d known Lou Reed only from his Levi’s commercial and only vaguely knew that Roger Daltrey was in a band, but I didn’t know Who (pun intended). I got my introduction to very real, very serious art thanks to The Pat Metheny Group and Laurie Anderson playing her violin with magnetic tape on her bow, manipulating the recordings into all kinds of odd sounds.

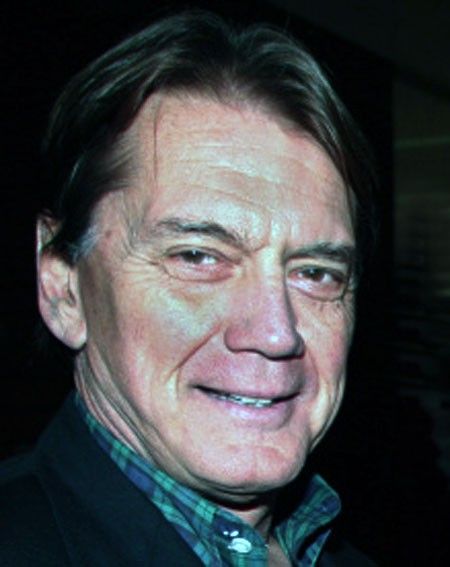

Speaking of odd, Tom Waits drunkenly croaked out his tunes with a droplight hanging from the top of his piano. On the opposite end of the vocal spectrum, The O-Jays knocked the crowd dead with their smoother-than-silk voices and dazzling choreography. In the words of their lead singer, Eddie Levert, “I liked-ed that show!” I’ve always wondered if you could see me in the video for Aerosmith’s “Let the Music Do the Talking” (recorded at the Orpheum in 1985), the filming of which was both exciting and boringly-repetitive. I don’t remember seeing 10,000 Maniacs in 1988, but I recall being captivated by their opening act, a Tufts graduate who some of us had seen busking in the subways, Tracy Chapman, who became the first Black artist to win the Country Music Association’s award for Song of the Year in 2023 (after Luke Combs recorded her song “Fast Car,” which she played at the ’88 Orpheum gig).

Soon after I began my ushering gig, I started developing my own musical tastes, which were radically different from my parents’. Violent Femmes became a favorite, feeding my teen angst and rage. Stevie Ray Vaughn’s blurred hands on the guitar introduced me to electric blues. Later, when I became obsessed with Bob Dylan, I saw several of his remarkable shows at the Orpheum. One night, he broke away from his longstanding set list to give us a gift of three extra songs. On another, he and Patti Smith sang a lovely duet of Dylan’s tune “Dark Eyes” that they’d performed live together only one other time.

Working at the Orpheum allowed me into other venues, too, since they were all run by legendary local promoter Don Law. We worked the Concerts on the Common shows in Boston, where I discovered that Don Henley, like Daltry, was in a famous band before going solo and topping the charts with “The Boys of Summer.” And when Great Woods (now Xfinity Center) opened in 1986, we were even issued embroidered polo shirts! Quite the step up from our Orpheum garb.

My Orpheum gig ended in 1989, when going to college left me too busy. Shortly after I stopped working there, I realized that I’d never be so plugged in to the music scene again. When I went back to the theatre in 2023 (to see my 50th Dylan show), someone had spent that million dollars I’d dreamed of having (and much, much more!) to renovate the place, and it was an incredible transformation. The walls were unscarred, the lobby mirrors not nearly as smoky. Hell, they even served wine and beer, which was unheard of in the early ‘80s when I was working the aisles. The seats were still too narrow, but the ceilings and details had been scoured and were more than a little impressive. Despite the major clean-up efforts, though, it still had enough of the faded beauty that I immediately remembered from my teen years and the scores of shows that I’d never thought I’d appreciate now as an adult. And one thing that was true for both my first and most recent trip to the Orpheum: I liked-ed it!

(by John Radosta)

Lifelong Boston resident John Radosta is the co-author (with Keith Nainby) of Bob Dylan in Performance: Song, Stage, and Screen (Lexington, 2019) and has written numerous articles about Dylan and Woody Guthrie for a variety of publications.